The emerging hydrogen market is “in theory, oversupplied of [hydrogen] projects, but of course not all of them are real,’ a McKinsey & Co. associate partner said. (Source: Shutterstock.com)

With a shortage of electrolyzers, manufacturers need to scale fast to meet what is expected to be heavy demand for hydrogen due to its potential as one of the world’s top decarbonizing tools, experts say.

However, if hydrogen producers haven’t reached final investment decisions (FID) on projects, manufacturers can only do so much when it comes to churning out more of the equipment needed to split water molecules using renewable electricity. Those hinge on securing offtake agreements. Factors at play include demand and costs, according to a panel of experts speaking recently at an energy and utilities conference in Austin.

In the U.S., clean hydrogen production for domestic demand has the potential to scale to about 10 million metric tons per year (mtpy) in 2030, up from less than 1 mtpy today, according to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Pathway to Clean Hydrogen Commercial Liftoff report.

“If you thought that all of that was going to come from green hydrogen, that would be something like 60 [gigawatts] to 100 gigawatts of electrolyzer deployment. Let’s say that half of it comes from green hydrogen and half of it comes from blue hydrogen,” said Tom Hellstern, associate partner for McKinsey & Co. “We’re talking 30 [gigawatts] to 50 gigawatts of electrolyzers. Globally, there’s only about 700 megawatts (MW) with an M, megawatts, of electrolyzers. So, this is an industry that probably needs to 50 to 100X to hit the types of targets the Department of Energy is talking about.”

Hellstern is confident the industry can rise to the challenge with policy and incentives now in place.

The Inflation Reduction Act, for example, includes the 45V Hydrogen Production Tax Credit of up to $3 per kg of hydrogen, depending on greenhouse-gas emission intensity.

Used mostly today in oil refining and ammonia production, hydrogen has the potential to decarbonize sectors such as steel, maritime and aviation; power fuel cells; generate electricity; and serve as a transportation fuel—displacing carbon-emitting fossil fuels.

While most of the demand is met today by hydrogen produced with natural gas as feedstock, hydrogen supplies with low carbon intensity are expected to rise, lowering emissions in the U.S. and abroad.

Electrolyzers are essential. The question is whether there will be enough.

“When we look at the pipeline of [hydrogen] projects, there’s about 10 gigawatts globally that are FID or beyond. So, expect 700 megawatts today, up to 10 gigawatts by 2025 or 2026,” Hellstern said. “Over 200 gigawatts have been announced by 2030. Globally, we don’t think that all of that is going to be built… We’re anticipating that this market is incredibly short electrolysis capacity for the foreseeable future, at least until the late 2020s.”

Offtake challenges

Offtake is among the hydrogen industry's biggest obstacles.

“In order for us to fill a factory for a capital-intensive product like an electrolyzer, we need to have what is effectively firm orders and therefore we need projects that have firm offtake to receive those orders,” said Alex Panchula, vice president of products of Massachusetts-based Electric Hydrogen, which makes industrial-scale hydrogen electrolyzers.

Plus, it takes time to see financial flows, given electrolyzers can cost millions of dollars depending on the size.

Another limiting factor is the project’s ability to secure debt financing, which Panchula said could open a pool of capital and allow projects to grow exponentially. However, bankers are not yet comfortable with risk-adjusted returns in the emerging hydrogen industry, which lacks the maturity level of pure-play wind or solar development, he said.

“Offtake is critical, and we don’t see enough of it,” Hellstern said, adding today’s early hydrogen adopters are niche offtakers.

“There’s actually more announced projects in hydrogen than we anticipate the demand to be. The market is, in theory, oversupplied of projects, but of course not all of them are real,” he said.

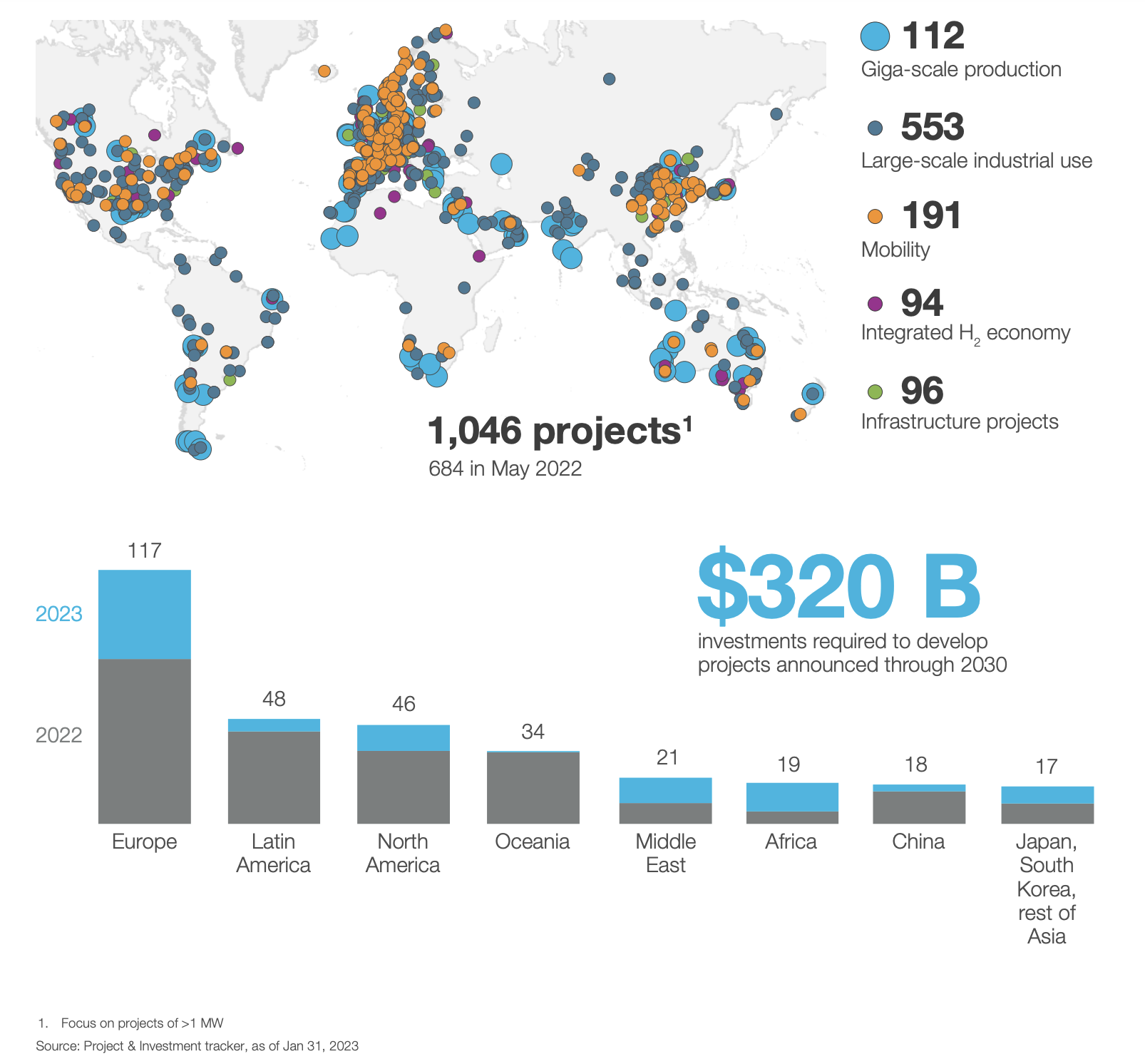

The hydrogen industry announced more than 1,000 large-scale projects—more than 1 gigawatts (GW)— globally by the end of January 2023, according to the Hydrogen Council. The announced projects require direct investments of more than $320 billion through 2030. Only $29 billion has passed FID.

“Because there’s not a lot of electrolyzers deployed in the world, the financiers, the infra-equity firms and the banks overall are thinking really hard about what are they willing to finance, at what premium for the risk and how you pick your electrolyzer—which company you go with ends up being a really important factor for that,” Hellstern said.

Getting costs down is another hurdle to overcome. A 500 MW electrolyzer requires about $1 billion of capex, according to Hellstern. Bump that up to $2 billion to $3 billon when you add in renewables.

Electrolyzer projects also have engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) hidden costs, Panchula added. Bringing down construction costs on a 500 MW or 1 GW scale project is an area of focus for Electric Hydrogen.

“A tiny mess up can cause change orders that could blow a budget quite quickly if an EPC has not done such a project before,” Panchula said. “We can probably learn from sort of the hockey stick growth of solar and attacking soft costs early.”

Solutions: scale, efficiency

With multiple variables at play, electrolyzer manufacturers are focused on scaling up, improving efficiency and bringing down costs.

“We’re like tiny little fish looking at this huge market,” said Everett Anderson, vice president of advanced production development for Nel Hydrogen. “All of our…focus is directly on scale at the moment.”

In May, the Norwegian hydrogen technology company plans to build its second gigawatt electrolyzer manufacturing facility in Michigan. The company is also scaling up its Norway factory to 500 MW per year. Nel Hydrogen manufactures alkaline and proton exchange membrane electrolyzers.

In business since 1927, Nel Hydrogen takes comfort in being able to point out its track record to banks, Anderson said; however, it’s still a challenge.

“There’s only so much you can get with scale from the manufacturing side. There’s innovation that needs to happen as well,” Anderson said. Nel has been working to improve designs and reduce materials to drive down electrolyzer costs and improve efficiency. “As you look at the overall levelized cost of hydrogen, efficiency becomes the most important factor over the lifetime of that project in order to get the lowest cost.”

Creative thinking could also lead to improved efficiency.

Hydrogen hubs are one way to get the hydrogen cycle going, but individual utilities can think about neighboring industries that may need hydrogen, according to Panchula.

“At that point, we can build gas networks incredibly quickly. We have proof in the Permian Basin that we can build huge gas networks incredibly quickly when the economic signal is there,” he said.

With a hydrogen network, costs are shared, and midstream partners can be brought in to help connect point sources of hydrogen to a distributed network. “It’s basically trying to grow small grids in localized territories. That’s, I think, probably the best way to approach the market.”

Looking for more inspiration, Hellstern also turned to the LNG sector, which reduced capex costs by about 20% to 30% between the first and third generation of Gulf Coast projects.

McKinsey recently updated its capex view for the Hydrogen Council, he said.

“We would say the cost of these projects are somewhere around $2,000/kilowatt today, which is probably 60%, or two-thirds EPC, permitting, everything that’s not the electrolyzer,” Hellstern said. “We think that that can come down pretty substantially to the point where electrolyzer costs drive down the project [cost] overall. But we see a roadmap to about 50% to 60% overall cost decline by 2030 as well.”

Recommended Reading

Dividends Declared in the Week of May 6

2024-05-10 - Here is a selection of upstream, midstream and service and supply companies’ dividends declared in the past week.

OFS Sector Loses Jobs, but Trade Org Says Growth Potential Remains

2024-05-08 - According to analysis by the Energy Workforce & Technology Council, the OFS job market may still have potential for growth despite a slight decrease in the sector in April.

Exxon Appoints Maria Jelescu Dreyfus to Board

2024-05-08 - Dreyfus is CEO and founder of Ardinall Investment Management, a sustainable investment firm, and currently serves on the board of Cadiz Inc. and Canada-based pension fund CDPQ.

E&P BW Energy Undergoes ‘Technical’ Ownership Restructuring

2024-05-08 - The restructuring will not involve any change to the ultimate control of BW Energy as the shares currently held by BW Group will be sold to BW Energy Holdings.

Hess Midstream Subsidiary Plans Private Offering of Senior Notes

2024-05-08 - The proposed issuance is not expected to have a meaningful impact on Hess Midstream’s leverage and credit profile, according to Fitch Ratings.