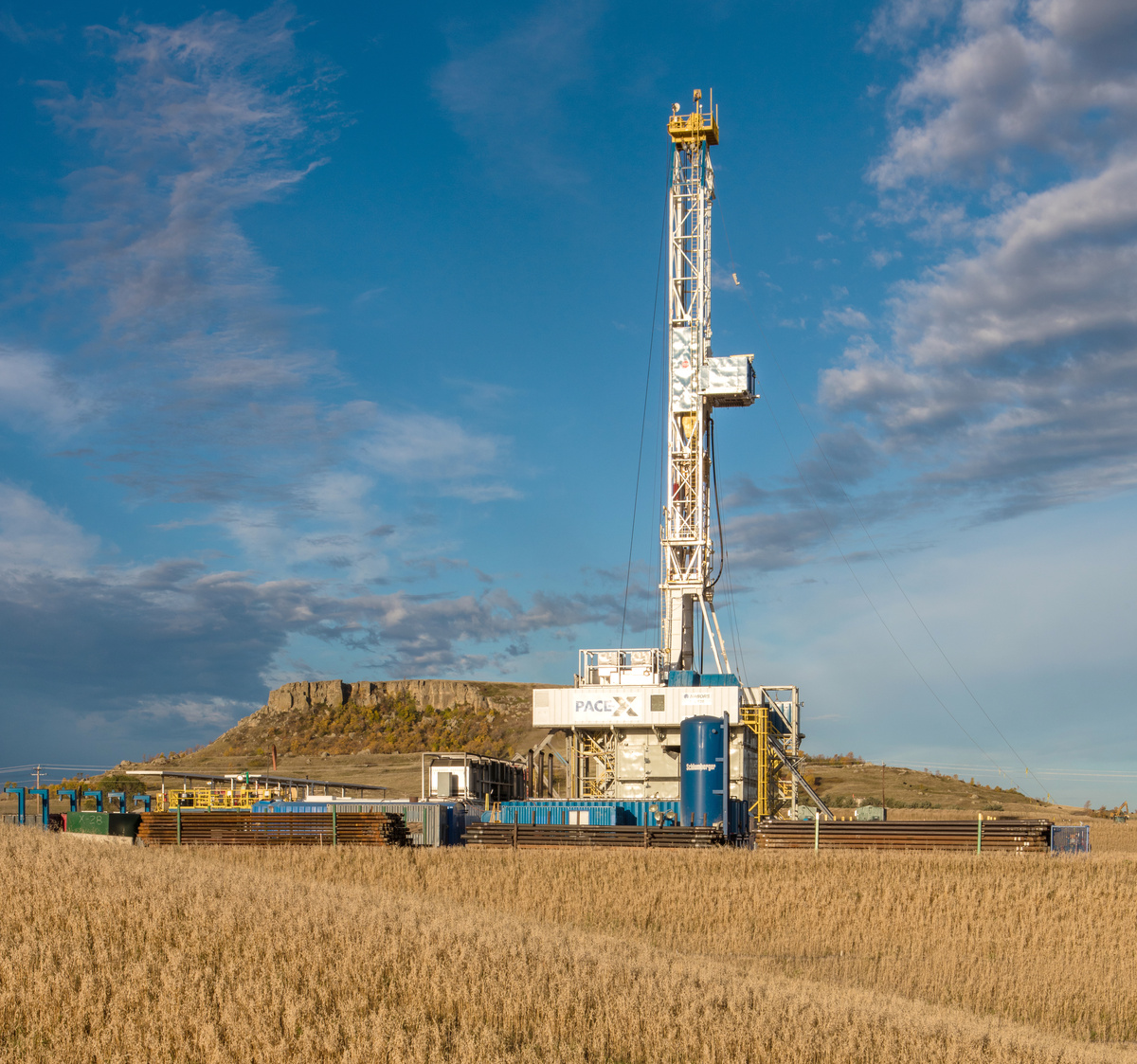

Hess’ use of data analytics and automation has helped the company optimize its Bakken drilling programs and increase its operational efficiencies. (Source: Hess Corp.)

Data today are what oil was to the early 20th century— revolutionary. Data are the backbone of the digital revolution, a revolution that Klaus Schwab, founder and executive chairman of the World Economic Forum, has proclaimed to be the fourth industrial revolution.

The road to this higher tech revolution started with the use of water and steam to power mechanized production. Electricity’s ability to power mass production delivered a second industrial revolution, with the third revolution made possible with the advent of electronics and information systems necessary to automate production.

Each revolution was made possible by oil and gas as the duo either replaced or is in the process of replacing coal as a primary power generation fuel source. And now the oil and gas industry is fueling future innovations through its use of data analytics to better understand the reservoir formations it pursues while maximizing production and increasing the value of its reserves.

Hess Corp. is one of many energy companies using data analytics to enhance its E&P efforts. What sets the company apart is its application of Lean manufacturing in its daily operations. The core tenet of Lean is to eliminate all waste from the manufacturing process, with waste being defined as any activity that does not add value.

“Hess is about value growth, so what we’re trying to do is deliver the maximum NPV [net present value] per drilling spacing unit [DSU],” Hess Corp. COO Greg Hill told attendees at Hart Energy’s DUG Bakken and Niobrara conference in March.

The company holds a balanced blend of domestic and international onshore and offshore assets. In the Bakken Shale the company operates about 550,000 net acres, including 350 DSUs to drill in the core of the Middle Bakken, more than any other operator in the area, according to Hill.

“In terms of future drilling operations, we have about 3,000 wells. About half of those 3,000 will generate a return of at least 15% or higher at current oil prices,” he said.

These returns are made possible by the company’s Lean-thinking army of problem solvers, all seeking to drive continuous improvement using processes and technology. Through a combination of technologies like proprietary algorithms, predictive analytics, machine learning, automation and more, the company has—in its second year of use—optimized its Bakken drilling programs and increased its operational efficiencies, delivering a reduction in cash operating costs by 32% from 2014 to 2016, according to Hill.

Barry Biggs, vice president of Bakken operations of Hess, told E&P, “We’ve driven our well cost down significantly over the years. We’re talking 60%, probably 70% reductions on well cost since 2012. You do that by collecting data. The data are used to understand the gap between the actual and targeted goal. The data are used to create counter-measures and can be operational, drilling or completions in nature, but data are the engines that drive problem-solving.”

Hess’ use of data analytics and automation has helped the company optimize its Bakken drilling programs and increase its operational efficiencies. (Source: Hess Corp.)

Well factory

For Hess, its North Dakota-based “factory floor” is more than four walls and a ceiling surrounding a long line of conveyor belts and assembly stations. It is the Middle Bakken and Three Forks formations; it is the land sitting above these formations, the drilling rig and more.

“We use the term ‘well factory’ to describe the process. It’s an assembly line for drilling for oil,” Biggs said. “But it is an assembly line that has engineering, has land, has the reservoir, all the way through to a well being drilled and handed over to operations at the end. We’ve put it all together in a value stream that we monitor and manage.”

There are 14 different stations on this assembly line of wells, according to Al Mueller, director of well factory planning and design for Hess.

“We go through each station, from well planning to building the well pads and then to drilling the wells. Facilities are put in place before the wells are completed and flowing back,” he said. “Across the whole well factory we’re looking two years ahead all the time. Each quarter is updated to show where we are going and what we are planning to do in the next two years.”

Each station in the well factory assembly line has a set amount of time to be completed, and the Hess team is always looking for ways to drive that amount of time down, Mueller said.

The well factory process is not just about drilling and completing the best wells, according to Biggs and Mueller. It is about maximizing the entire value stream.

To do this, the company relied on the data to show the best path forward and found that there are three ways to do this in the core of its Bakken assets: well spacing, reservoir entry points for fracture initiation and proppant load.

The company uses what it calls a “nine and eight” for its well spacing, that is, a target of nine Middle Bakken Formation wells and eight Three Forks Formation wells on a single pad located over an area where the two formations are productive.

“I think this is a competitive advantage for us. We can put 17 wells in on a single DSU pad,” Mueller said. “Our value is going to be much higher, and I can maximize the value of each and every DSU. To do that, we have 250 ft [76 m] between the Middle Bakken and Three Forks wells for spacing. We think this type of spacing is key.”

The company uses a “nine and eight” well spacing to drive maximum value from its DSUs. (Source: Hess Corp.)

There is a trend of some companies going in and drilling infill wells between the other wells, according to Biggs, but this is not preferred by Hess because there is value lost.

“What we saw when we tried to do this and what we’re seeing happening now is that you cannot get near the productivity you would get if you did it all originally at the same time,” Biggs said. “That’s because the rock has changed [and] all of the stresses in the rock are changed. So the new well you put in between two other wells is going to preferentially go the route of least resistance and connect with the fractures from the other wells, resulting in lost value.”

According to Mueller, another key to success is the use of sliding sleeves in its completions because it helps keep costs in check.

“Sliding sleeves really help us to ratchet down our costs,” Mueller said. “We’ve done a couple of plug-andperf completions on wells to see if it would be better and were unable to see any real difference. I think others maybe have shied away from tight well spacing. We like our wells to interact a little bit.

“The reason for that is that we want to effectively drain the reservoir in between wells. We want to crush as much of that rock up as we possibly can. If we’re not seeing that interaction, then that’s telling us we’re not doing as much as we should be doing.”

Mueller continued, “That’s the way we think of it. Our individual wells may not be as good as individual wells from other operators, but when you look at the DSU value—how much we’re getting out of the DSU— we’re certainly in the top quartile, and so a key part of our strategy is to keep the tighter well spacing.”

The application of predictive analytics on not just Hess’ data but the well data for all operators that are made public by the North Dakota Industrial Commission is what helped dial in the best settings for Hess’ success in its Bakken wells.

“It was 2014 when we really started working with the data,” Mueller said. “Over time we’ve assembled a very large dataset. One of our first big successes with this was moving from 35 stages to 50 stages. We got a significant uplift in production with that, and it turned out to be very close to the prediction that we had using our predictive analytics.”

That nearly accurate prediction gave the team confidence in the technology, he said.

“What’s really interesting is that we are able to predict the wells based on the geology, completion design, well spacing and well configuration. Knowing all of those things, we can predict how that well will respond and what kind of productivity we will get from that well,” Mueller said.

“We can do this for our wells and the competitor wells. We’re within plus and minus 3% of that well productivity number of the wells completed in 2016 using this technique, which I think is pretty amazing in that we can get that close to ours and other wells with all these different variables. That’s where the machine learning comes into play. The framework keeps getting more and more accurate all the time, the more data it gets.”

In 2017 the company is investigating the benefits in increasing the number of stages from 50 to 60. “Going from 50 stages to 60 stages, we see there is a bit of diminishing returns, but we think that 60 will still be value-adding,” Mueller said. “We have enough confidence in the predictive analytics that we try to let it tell us what to do [or] the next thing we should try. It is a big help because there’s a ton of different things you could try, and even if it is not exactly right, it does get you in the right direction as to what you want to do.”

The evolution from 35 stages to 50 stages is the result of a pilot testing, according to Mariano Gurfinkel, senior adviser for the global onshore business unit at Hess Corp. “We have a standard design, and we do that very well,” he said. “However, we are always looking for ways to eliminate waste. To do that, we create pilot programs that allow us to optimize the design using predictive analytics and physics-based modeling. That is what allowed us to increase the number of stages.”

Work continues to determine if 60 stages is a possibility, along with other elements like adding more sand, Gurfinkel added.

“Historically, we’ve been very different from other operators in that where we went tighter in spacing while other operators went with more intense completions,” he said. “What we see now is that our competitors are trying to get tighter spacing, and we’re increasing the intensity of our completions. The way I see it, there are two trains that will eventually be in the same place.”

In addition to predictive analytics, the well factory team is working on ways to automate its processes. “Automation will make a big difference. If we can automate processes, then we can have our people doing more value-added work. We’ve continued to improve on this, but even now we are not satisfied with what we can do with automation,” Mueller said. “A big thing we’re looking for moving forward is to improve on the automation and have our people working on the tougher problems and not worrying about the things that can be automated.”

Smarter ‘house calls’

Well operators today—like the doctors of yesteryear— make “house calls.” From well to well the operator checks on each to ensure all are healthy and functioning properly. However, rather than wasting a ton of time driving around checking on healthy patients only to find a sick one and not be prepared to treat it properly, Hess takes a different approach with its use of exception- based surveillance.

“We instrument our well sites with a fair amount of instrumentation,” Biggs said. “That instrumentation is feeding back information on the health of the well.”

The data are continuously screened so that when well operators check in at the start of the day, they are able to see which wells are “sick” and in need of attention, he added.

Value is added to the overall process by equipping highly trained well operators with the right data ahead of time.

“For example, say an operator checks a well that is showing a production-related problem and finds that the problem is not fixable. The well operator notifies the engineering team to look further into the issue,” Biggs said. “It’s all down to the people, processes and technology working together.”

Exception-based surveillance is one side of the operations coin. The other side is having the right tools and materials ready when maintenance is needed.

“I think what makes our use of machine learning and data unique is in how we package those data,” Biggs said. “We’ve worked hard in operations to get people and materials to the right place at the right time.”

Step one is robustly outfitting the well with sensors and instrumentation so that a well operator knows when there is an issue that needs to be addressed, Biggs said. The second is ensuring the repair crew has the necessary parts to get the well back online when they get there.

“The driving times between locations are horrendous in North Dakota,” he said. “What I absolutely don’t want is to have a maintenance crew get to a sick well and not have the parts and tools necessary to do the repair.”

To ensure that this does not happen, the company has integrated its production monitoring system with its SAP maintenance systems. “It is called our work and material flow. When a work order is generated within our SAP maintenance system, a list of materials is generated. Those materials are kitted up and ready to go in the warehouse. When the repair crew comes by, they can pick up the kit that has all of the repair materials for the well,” Biggs said. “Not only do they get a kit just for that repair job but for every job they are scheduled to perform that day.”

When a repair work order is issued, failure codes are entered that flag the company’s reliability engineers. “We use this feature so we can determine who the ‘bad actors’ are in the field and determine if a deep-diving engineering review is necessary to come up with what preventative maintenance can be done to mitigate those failures in the future,” Biggs said.

Harnessing the disciplined approach of Lean manufacturing with the power of data has proven to be a winning combination for Hess Corp. in all areas of its business, onshore and offshore. The two have revolutionized its operations in much the same way that oil and gas ushered in not one but four industrial revolutions.

The integration of Hess’ production monitoring system with its SAP maintenance systems has made it possible for the company to identify wells needing repair and to have the materials ready to repair those wells kitted up for when the repair crew arrives at the warehouse. (Source: Hess Corp.)

Contact the author at jpresley@hartenergy.com.

Read June E&P's other Big Data Analytics & Applications cover stories:

Big Data IoT transforming the industry

Making oil, gas data analytics projects deliver

You can see the future from here

Bringing the IIoT to the oil patch

Supercomputer facility expands capabilities in exploration, reservoir management

Recommended Reading

Delivering Dividends Through Digital Technology

2024-12-30 - Increasing automation is creating a step change across the oil and gas life cycle.

E&P Highlights: Dec. 9, 2024

2024-12-09 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a major gas discovery in Colombia and the creation of a new independent E&P.

E&P Highlights: Dec. 16, 2024

2024-12-16 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a pair of contracts awarded offshore Brazil, development progress in the Tishomingo Field in Oklahoma and a partnership that will deploy advanced electric simul-frac fleets across the Permian Basin.

Shale Outlook: E&Ps Making More U-Turn Laterals, Problem-Free

2025-01-09 - Of the more than 70 horseshoe wells drilled to date, half came in the first nine months of 2024 as operators found 2-mile, single-section laterals more economic than a pair of 1-mile straight holes.

Tracking Frac Equipment Conditions to Prevent Failures

2024-12-23 - A novel direct drive system and remote pump monitoring capability boosts efficiencies from inside and out.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.