The U.S. is producing more oil and gas than ever, and global demand has continued to tick up. But it takes a lot of planning and equipment to power these operations, and that’s where EthosEnergy steps in.

Ten-year-old EthosEnergy, based in Aberdeen, Scotland, and Houston, is a services provider with a worldwide footprint specializing in rotating equipment for the power, oil and gas, and industrial sectors. The firm focuses on gas and steam turbines, generators, compressors, transformers, field services, operations and maintenance.

The company is a joint venture between Wood and Siemens AG, but change is in the air with Wood announcing earlier this year it plans to sell its controlling 51% stake in Ethos.

That change was announced Aug. 28 when private equity firm One Equity Partners (OEP) agreed to buy Ethos for an undisclosed sum, including Ethos' 3,600 employees across 23 global sites. OEP, founded in 2001, spun out of JP Morgan in 2015.

Ana Amicarella joined EthosEnergy as CEO five years ago after previously working at Aggreko and GE.

She knows a lot about teamwork and leadership after representing Venezuela in the Olympics as a synchronized swimmer following an All-American collegiate career at Ohio State.

She spoke with Jordan Blum, Hart Energy’s editorial director, about the technologies and trends powering the energy sector.

Jordan Blum, editorial director, Hart Energy: Starting off broadly, what’s your overview of how Ethos operates as a specialized joint venture for Wood and Siemens?

—Ana Amacarilla, CEO, EthosEnergy (Source: EthosEnergy)

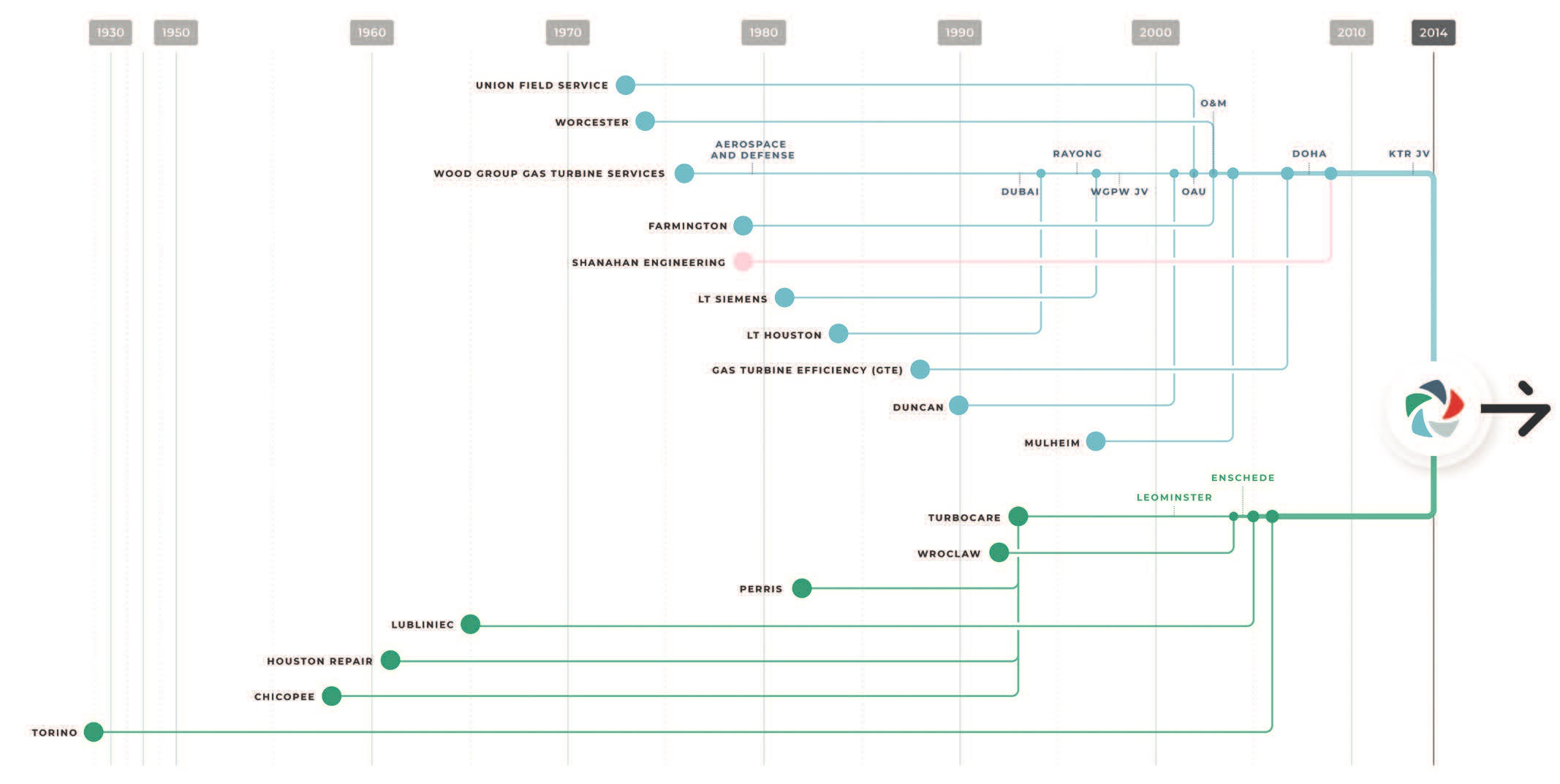

Ana Amicarella, CEO, EthosEnergy: The joint venture was started simply because I think Siemens wanted to exit what is called the non-OEM [original equipment manufacturing] piece of their business. They had a business called TurboCare that they put into the joint venture. On the other hand, Wood had a gas turbine services group that did a lot of GE work, but with other OEMs, as well. Neither of them saw that as a strategic business for them. So, they put them together and created in 2014 what is today EthosEnergy. That was the beginning of the joint venture. Advance to today, they still feel that it’s not strategic to their core and they’ve actually put us up for sale. So, we are in the midst of a sale of the business. I’m very excited.

This company is made up of many, many acquisitions of businesses [some of which date back 100 years]. With many, many businesses, what I inherited five years ago was a [combined] business that was not properly integrated. It was so many different cultures, different things. I remember walking through my first year at Ethos and people telling me, “Oh, I work for TurboCare” or “I work for GTS,” and I’m like, “Who? I thought you worked for Ethos.” Everybody was in a silo. We would have five people go to a customer in the same week and they didn’t talk to each other, and it created massive confusion.

So, we have evolved from being a very poorly integrated business to an enormous transformation that we’ve undertaken in the last four and a half years to become what I call the “One Ethos.” We have to understand what the customer is looking for. What is the problem we’re trying to solve? Then, take your parts and pieces, put them together and, in turn, provide a solution to the customer. It’s about understanding their pain points, understanding how the customer makes money, and then tailoring a solution with our tools that will bring the customers quantifiable value. And that’s how we differentiate ourselves. We’ll give you a customized solution with the entirety of the portfolio that I have behind the curtain.

JB: Can I get you to elaborate on the often, I’d say, overlooked importance of the parts for powering and servicing all the energy operations, upstream and downstream? And what are the biggest challenges?

AA: Let me talk to the industries that we work with. Utilities—their responsibility is to generate power. That’s a very simple model. You have units; they’re running just like your car. At some point, you need to stop and give them service. When I say industrials, it will be continuous processes mostly. So, something like a paper mill or a steel mill requires constant energy, and you can’t have an outage. Those people over the last 20, 40 years have invested in their own power plants, which are smaller. It has to continue to rotate.

For the oil and gas industry, it’s the same thing, often continuous. It’s a necessity, right? In upstream, you’re drilling; sometimes you’re drilling in remote areas. Midstream, you’ve got to transfer the gas. Downstream, you’ve got petrochem and refining. You have safety issues. It’s an enormity of things. These people have power plants, but they’re great customers because they don’t know anything about turbines versus the utilities. The utility knows turbines. These people, they don’t know turbines, but they have to have them. It’s like they bought it, but then they don’t know how to operate it.

And then you have the other set of customers, which are the IPPs [independent power producers]. IPPs have the money, but they don’t have the know-how, they don’t have shops, they don’t have operators, they don’t have technicians. They just have the money. So, they hire us to come and run their facilities. We are their brain. On top of that, we do the maintenance. When I speak about maintenance, it’s four parts: parts, field services, repairs and upgrades.

The beautiful thing happening with the energy transition is that people have realized they need their assets to run longer. They need new life because, as it turns out, the renewables are not coming in at the speed that people would like, and not to mention they’re intermittent power sources. We go to the customer with a customized solution. If you only need the power to run for three years, it’s one solution. But, if you wanted to run for 20, it’s a very different solution. That’s how we bring a lot of value.

JB: On the oil and gas side of things, I know you do a lot of both, so can you elaborate on the differences and challenges of powering and servicing onshore versus offshore oil and gas?

AA: We do quite a bit of offshore North Sea, very big in Kazakhstan, very big in the Gulf [of Mexico]. With offshore, you have to be extremely good because it is an island, and when you go, you need to have everything on hand. You’ve got to plan a whole lot better. We had a customer with very lousy reliability of its rotating equipment on the platform, like 50%. It was the most painful asset they owned. They said, “Ethos, we need you to fix this.” I said, “Measure us on our ability to go from 50% to over high 90s.” We’ve done that. They said, “It has gone from being the most troubled asset in our portfolio to our best asset.” And it’s old. When you go offshore, you’ve got to fly a helicopter to get people there. You’ve got to think about the parts and how you are going to get in there. So, your planning for the materials and personnel is enormous. You’ve got specialty training, the preparedness, the safety, the planning. And, of course, with that comes a [price] premium, which is beautiful for us. But they need things to work. Everyone has read in the news what happens when things don’t, right?

JB: What trends or interesting developments are we seeing in terms of gas versus steam turbines? Compressors and other critical equipment?

AA: I’ve been around for quite a long time, and it is just so fascinating to see how some of these customers are shifting their models, especially the small independents. They’re saying, “Look, instead of extracting gas and oil, we’re going to reinject CO₂.” That’s a blow-your-mind sort of example. But, it turns out you need the same equipment. You need the compressor and the turbine to do that operation, and the compressor and the turbine, frankly, couldn’t care less if you’re going out or going in. It’s just a reverse operation. Customers are coming to us and saying they need to repurpose this equipment because they are shifting their business model. I’m like, “No problem. We have a solution for you because we have repurposed the equipment.”

Another thing that I’m seeing is the enormous need for power. I was with one of the majors a couple of months ago, and they need more big power. These people are now getting into bigger power production to [keep] their assets running. They have a [greater need for] power to satisfy some of these carbon capture projects. And, of course, everything that is going on with some of the customers that are building artificial intelligence and cloud facilities. Let’s say a big resort hotel may have a need for 1 MW [megawatt]. What these people are building is these complexes for AI and cloud computing where they have not one building, but maybe have three to eight buildings. Instead of a 1 MW load, it’s an 80 MW load. How can a utility that’s slow at getting approvals deal with this enormous pent-up demand that this AI revolution is bringing? They’re building these complexes. In the U.S., it is a huge transformation, and that’s why all these assets need to keep running. They’re saying, “Remember that nuclear plant we were decommissioning? Remember that coal plant we were decommissioning? We need to bring those back.”

As much as I want to help my customers decarbonize, they’re asking me for help to give them more power. And it’s not a little bit—it’s enormous. The Microsoft guys say this is the biggest revolution we’ve seen, this AI revolution. And that’s going to need a lot more natural gas and other supplies. And natural gas is pretty clean. The OEMs have come up with incredible technology to make that power pretty clean. And what customers are saying is, “We need more power, more reliability, more availability, more megawatts.”

JB: How is the ongoing electrification of the oilfield impacting the business?

AA: A lot of the big oil companies are electrifying their fields. But what does that mean? What that means is you’re going to need more power. You are putting a motor instead of a compressor to run. Now, you have a load, and that load requires megawatts, and those megawatts require a turbine. It’s the same end results—you need more power. It’s a trend that’s driving up the demand for power.

JB: Switching to Europe, I know you’ve grown a lot in the North Sea. How is that evolving?

AA: I’ll give you an example. In the North Sea, a company [Harbour Energy] bought assets, brought them together … and it happens to be the largest producer now in the North Sea. So, when I first went to see them, I said, “Look, you have all these disparate assets, and these assets are from all the different OEMs. If you want to simplify your supply chain, nobody can work in all the OEMs that Ethos can.” I’m able to bring the whole of those disparate assets to life and bring you reliability, or more power, etc.

JB: Moving geographically, what about the work you’re doing with KTR and Kazakhstan as well?

AA: We probably handle 60% of the oil extraction in Kazakhstan. Multiple majors and some medium-sized companies like Eni and Shell pull together and they operate in different platforms there. We formed a joint venture in Kazakhstan with a local partner, KTR, where we have inserted our intellectual property into their shop, and we’re able to operate right from Kazakhstan. We have an enormous advantage versus the OEMs to do that kind of work. We bring people in from the outside, but we have a sizable team locally in Kazakhstan that travels to the platforms and operations to make sure the rotating equipment is operated to the conditions that they want.

JB: Back in the U.S.—but feeding the rest of the world—you’re growing a lot in LNG as well, right?

AA: We have positioned our business to go eat the competition’s lunch as it relates to LNG. Why? A, it’s a continuous process. B, they tend to pay a premium because it has such a need for power. It requires highly specialized knowledge, and very high expectations on service. It’s a space where we have more expertise than our big competitors because we own the intellectual property [rights] for the parts and machines. We’ve made great inroads in LNG, and I suspect that will continue to grow because of the energy security needs.

JB: What are some of the main technical challenges that stand out when it comes to the specialization work for powering LNG facilities?

AA: It goes back to the continuous processes. They don’t want to have an outage. They need to run longer. So, you need to have parts that—instead of being changed every 16,000 hours—can be changed every 24,000 hours. Remember, these are hot gas parts, so there’s a lot of wear and tear. I like to use the car example because it’s frankly just the same. It’s just a little bit more sophisticated. You’re running hot, you need specialty metals, you have a combustor, you have very extreme amounts of energy, so you need different coatings and different materials so that parts can run to 24,000.

JB: I just wanted to squeeze in one more personal question. You have the background as an Olympic athlete as well. How does that experience translate to the energy sector and to leadership roles as well?

AA: You don’t have to go to the Olympics, but I believe very strongly that sports give you a unique advantage in leadership. I look at my children and sports give you discipline. You’ve got to get up early every day, and then you give it your best, and then rinse and repeat. You go to bed early, you can’t eat junk and drink and smoke. You build this level of discipline, this ability to work when you’re tired, the ability to have teamwork built into your DNA. It’s all of the things that you need to be a leader and win, yet be humble.

Recommended Reading

Nabors Closes $370MM Parker Wellbore Acquisition

2025-03-12 - The acquisition of Parker Wellbore adds a large-scale, high performance tubular rental and repairs services operation in the Lower 48 and offshore U.S. to the Nabors portfolio.

Nabors SPAC, e2Companies $1B Merger to Take On-Site Powergen Public

2025-02-12 - Nabors Industries’ blank check company will merge with e2Companies at a time when oilfield service companies are increasingly seeking on-site power solutions for E&Ps in the oil patch.

Prairie Operating to Buy Bayswater D-J Basin Assets for $600MM

2025-02-07 - Prairie Operating Co. will purchase about 24,000 net acres from Bayswater Exploration & Production, which will still retain assets in Colorado and continue development of its northern Midland Basin assets.

Atlas Energy Solutions to Acquire OFS Power Company Moser for $220MM

2025-01-27 - Atlas Energy Solutions said it will purchase Moser Energy Systems in a cash-and-stock deal that adds power services in the company’s core Permian Basin operating area.

Appalachia, Haynesville Minerals M&A Heats Up as NatGas Prices Rise

2025-04-03 - Several large Appalachia and Haynesville minerals and royalties packages are expected to hit the market as buyer interest grows for U.S. natural gas.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.