It is impossible to outline the significance of the milestone anniversaries for the venerable U.K. Continental Shelf (UKCS) offshore region—the whole of E&P would have to be dedicated to them to do the region justice. In a nutshell, though, 2015 is of particular historical note because of the following events:

• The UKCS has now seen half a century of activity, since BP’s Sea Gem jackup rig struck gas on the West Sole Field in September 1965;

• Tragically, it also represents 50 years since the sector’s first offshore disaster, when two of the same rig’s legs collapsed on Dec. 27 as it was being lowered to move onto its next job, resulting in the loss of 13 lives;

• About 45 years have passed since BP discovered the giant—and still producing (thanks to Apache Corp.)—Forties Field in October 1970, just 10 months after the U.K. sector’s first oil field (Montrose) was found by Amoco and the year before Shell discovered the Brent Field; and

• It has been 40 years since the U.K.’s first offshore oil began flowing from the Hamilton Brothers’ Argyll and Duncan fields in June 1975, followed in November by the Forties Field when it started piping crude to Scotland’s Grangemouth refinery.

Just to put that into some wider perspective, 1965 also was the year that the Hollywood flick “The Sound of Music” topped the U.S. box office, with the James Bond movie “Thunderball” No. 1 on the U.K. film charts. On the music front, meanwhile, “Day Tripper” by the Beatles ended the year at No. 1 on the U.K. charts, while the Dave Clark Five topped the U.S. charts with “Over and Over.”

Current status

Fast-forward to today, and those heady days are indeed long gone. So what is the current condition of the U.K. offshore sector?

First readings are not encouraging—exploration drilling activity is at virtually an all-time low, with just 14 exploration wells drilled last year and 18 appraisal wells, including sidetracks. Possibly only between eight and 13 exploration wells are expected to be drilled this year (with seven drilled as of July), and just a handful of appraisals are anticipated. The number of development wells drilled last year was 126 including sidetracks, which is slightly higher than in 2013.

Production last year was 1.42 MMboe/d, which, according to the industry’s representative body Oil & Gas UK, was the best year-on-year performance in 15 years. However, it still is a declining production profile, being 1.1% less than the prior year.

Of greater concern is the fact that only 50 MMboe of potentially commercial reserves were found in 2014, which is far lower than the annual average of about 250 MMboe during the previous decade. Only eight new fields were sanctioned for development.

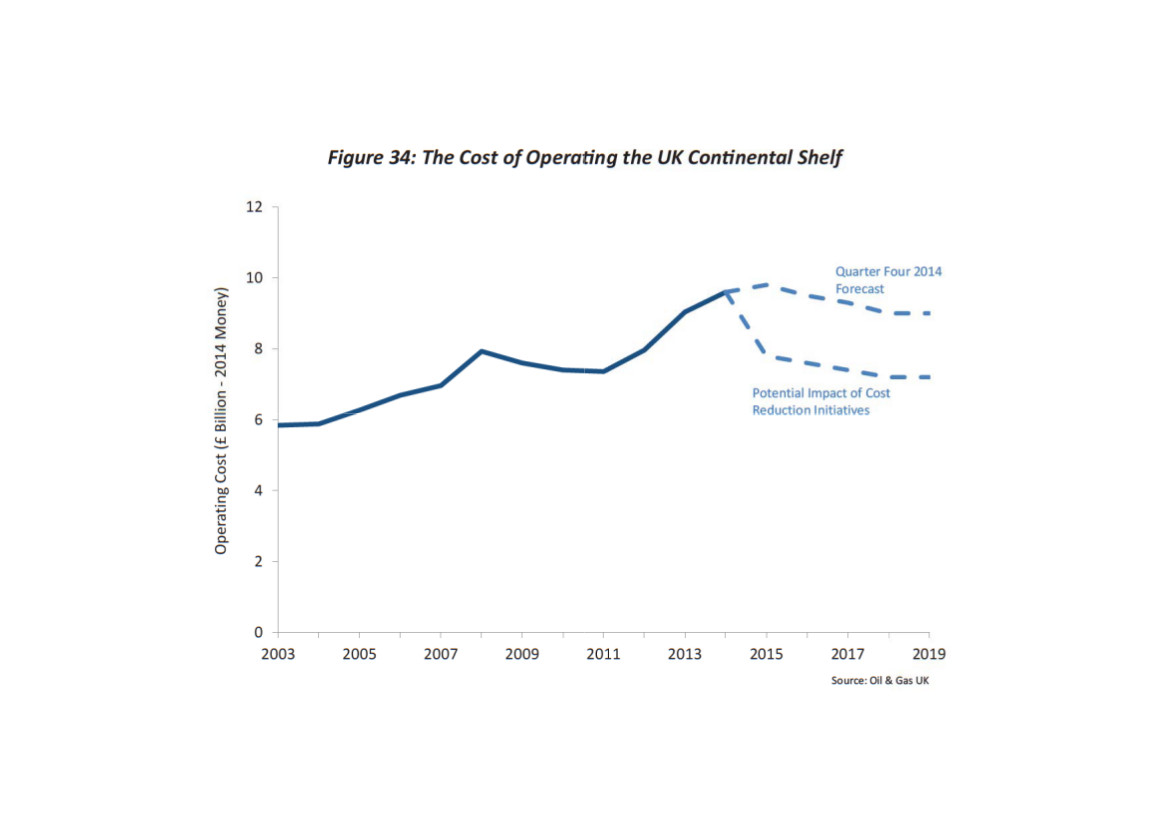

Most concerning, however, in light of today’s lower oil-price environment, are the running costs. According to Oil & Gas UK’s figures, unit operating costs had risen in 2014 to US$28.90/boe (£18.50/boe), up from US$26.50/boe (£17.00/boe) in 2013. That was at a time when the oil price was still averaging nearly US$100/bbl but beginning its plunge toward US$55/bbl by the end of December 2014.

Changing tide

The U.K. sector is, however, working hard to change this grim outlook, and the early signs are giving strong cause for long-term optimism.

According to analyst Wood Mackenzie, capital and operating costs in the U.K. upstream sector will fall steadily this year as operators continue to respond to the lower oil price. The biggest reductions will come in drilling costs, which could fall by one-third by year-end 2016.

Near-term pre-final investment decision (FID) field developments are expected to be best placed to benefit from these reductions, with development costs potentially falling by up to 20%, according to the analyst.

Operating costs will decrease by up to 15% in the U.K., with Wood Mackenzie asserting that upstream cost deflation is inevitable for the region as it exits a period of more intense development activity over the past five years. That has been the root cause of severe cost inflation as operators competed for already-expensive access to offshore services.

In one of Wood Mackenzie’s latest reports, Malcolm Dickson, principal North Sea analyst, said, “High capital and operating costs are the single biggest issue for companies in the U.K. and Norwegian sectors of the North Sea today. Even before the oil price crash, [being able to] develop and operate fields while making a profit was challenging, and we expected some cost deflation in the sector as activity cooled.

“The drop in oil prices has accelerated the need for lower costs as companies adjust to protect their cash flows, and changes are now required to correct the industry’s cost base.”

According to Dickson, rig rates already have dropped significantly, with reductions of up to 20% for new contracts agreed to in 2015. Of mobile rigs in the U.K., 40% (and 23% of mobile rigs in Norway) are either currently without contract or are due to come off by year-end 2015, giving scope for high reductions in future contract renewals, he said.

Upstream capital investment is continuing to fall this year in the U.K., with competition within the supply chain increasing as operators scrutinize costs and project execution. “As well as looking internally for efficiency gains, North Sea operators are now negotiating with contractors,” Dickson added. “This is because the opportunity for cost reductions is highest in uncontracted

spend such as pre-FID projects and new brownfield developments.”

Dickson went on to add that in general Wood Mackenzie expects to see costs fall a little further and quicker in the U.K.—for instance, lower rig utilization will mean cheaper drilling. However, he added, many of the U.K.’s new projects “are technically challenging, and standardized solutions are not an option, meaning there are few contractors capable of supporting them.”

According to Wood Mackenzie the remaining pre-FID projects are smaller (averaging just US$375 million in capex) and are generally operated by independent E&P companies, so economies of scale within the supply chain are harder to achieve.

Knowing that so much remains dependent on the level of the oil price, Dickson summed up his view going forward, saying, “Assuming the oil price rises as we think it will, the lower cost base achieved over this year and next can only be sustained through fundamental changes in practice and increased collaboration between the operators and the service sector.”

Rampant inflation

Such changes cannot come soon enough for some, with the rampant cost inflation that U.K. North Sea producers have been battling against for years being starkly highlighted at a recent industry event in Aberdeen, Scotland.

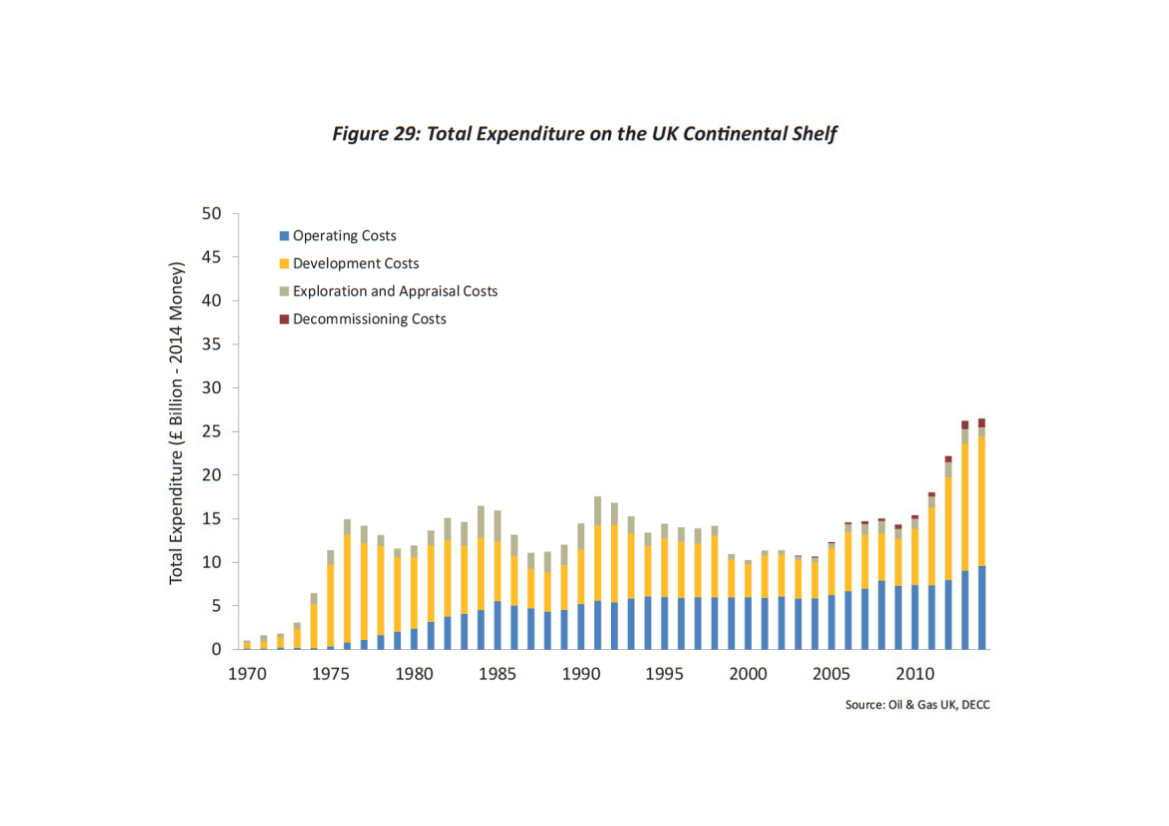

Dan Cole of McKinsey & Co.’s Londonbased oil and gas practice described offshore inflation as “way out of line” compared to the general economy. The annual rise in inflation in the U.K. during the period from 2000 to 2014 was 2.5%, but the cost of operating an offshore installation went up by 12% per annum in that period. Meanwhile, the development cost per barrel

rose by 21% annually between 2004 and 2013.

Cole told a recent Oil & Gas UK business breakfast that with an oil price of US$55/bbl, nearly half of all North Sea fields were uneconomic. To paraphrase this, he pointed out that if the fast-food industry had faced the same inflation rate, a burger in the U.K. that cost £2 (US$3.10) in the year 2000 would cost a staggering £13 (US$20.17) today. For those who don’t eat fast food too often, the price of a 2015 burger is still priced at less than £3 (US$4.66) in the U.K.

Cole added that cost inflation in the oil and gas industry was not due to increased activity or the supply chain becoming more profitable but rather was due to higher wages and greater inefficiencies.

A way forward, he continued, was to consult with the aerospace and automotive industries, where cost inflation since the start of the century has averaged just 1% a year. Aerospace manufacturing has kept costs down by parts standardization and by more collaboration with the supply chain, while the automotive sector has benefited from standardization and increased collaboration between rivals.

Sustainable at $60/bbl

According to Oil & Gas UK’s recently-installed CEO Deirdre Michie, the U.K. offshore sector simply has to become sustainable in a US$60 world. Speaking at the association’s annual conference in Aberdeen, she said that at US$60 oil, 10% of the U.K.’s production “is struggling to make money. There is a shortage of capital and a shortage of investors willing to place their money here.

“We need to think about this from an investor’s point of view,” she continued. “Given that we compete for investment dollars on a global basis, we must ensure the U.K. is a commercially attractive and predictable place in which to invest. Learning from our mistakes, we know that our focus cannot merely be on ‘cutting costs’ but must more fundamentally address the efficiency of the basin. Focusing on efficiency means that, if or when the oil price bounces back, we will be best placed to seize new opportunities.”

20 Bbbl prize

The prize to be won remains substantial, she added. “With over 20 Bbbl of oil and gas still to play for, there’s plenty of opportunity to ensure an indigenous supply for the country. On a global scale we might be a small player, but we’re also a world leader. Our technical expertise is unsurpassed and is reflected in the quality, the capability and the success story that is our supply chain.

“I’m pleased to be able to say that we have come together, aligned as to the prize our industry still offers. In keeping together, we have already made progress with the [new regulatory body] Oil and Gas Authority being set up, positive fiscal change being delivered and the industry working hard to improve its competitiveness.”

Some initial steps undertaken this year already include a consultancy being commissioned by Oil & Gas UK to carry out a survey of daily rates paid to independent contractors, allowing companies to benchmark their rates against the market. It also has established a database of spare parts held in inventories across the sector, which will allow replacement equipment to be

sourced quickly and efficiently with the aim of reducing production downtime.

Michie said there was “increasing evidence that big strides are being made to improve the efficiency and reduce the cost of operations. Lifting costs are anticipated to fall as a result over the next 12 months.”

The end target is an ambitious 40% improvement in unit operating costs. Wood Mackenzie has estimated that 1.3 Bboe of development opportunities will become available if the industry can achieve the targeted cost and efficiency improvements.

U.K. government support

The U.K. government has finally appeared to acknowledge the very real threat to the industry’s existence and is playing its part with tax reforms confirmed in the latest budget along with more direct support to help improve competitiveness.

Chancellor George Osborne cut tax rates on North Sea production, saying that this would help boost oil production by 15% by the end of the decade. Tax rates on production from older fields will be reduced from 80% to 75% immediately and are backdated to January, while the rate on newer fields will be cut from 60% to 50%. The corporation tax also is being

cut by 2% over the next five years.

The government will fund new seismic surveys via the OGA to the tune of US$31 million (£20 million) to assess the potential in underexplored areas of the U.K. sector. The two immediate priority areas chosen are the frontier region of the mid-North Sea High and the Rockall Trough basins, for which only sparse seismic information currently exists.

Modern 2-D seismic technology will be used to secure more detailed images of subsurface geology and geophysical properties to improve understanding of these areas. Invitations to tender for the work were posted earlier this year with the aim of beginning acquisition this summer and delivering the final processed datasets by the end of March 2016.

Collaboration is key

One example of how the industry is reacting to the call for collaboration is a forum that has been set up to address challenges in subsea integrity management.

The subsea-focused SURF IM Network is now in its second phase and has been extended for a further three years. Led by Wood Group Kenny with support from the U.K.-based Industry Technology Facilitator (ITF), Phase 1 was launched last year and was supported by a group of 14 operators.

The network facilitates face-to-face and virtual forums for knowledge sharing and delivering solutions to subsea integrity and reliability challenges, focusing particularly on subsea hardware. The first phase saw progress made in understanding the issue of control system module reliability, and the findings of a comprehensive participant survey were presented to subsea suppliers to highlight integrity challenges and find ways to enhance future reliability.

“Taking a standardized approach to complex subsea integrity issues that are common across the industry can help to drive efficiencies while creating a safer operating environment, so the network is a win-win for all involved,” said Dr. Patrick O’Brien, CEO for ITF. “It is a great example in the current climate of operators collaborating to support the development of effective and cost-efficient means to inspect subsea facilities that are being installed in continually increasing water depths and with longer step-out distances.”

Well intervention focus

Another area flagged for further work is well intervention. According to Martha Vasquez, a manager with consulting firm McKinsey & Co. who spoke at the Offshore Well Intervention event in Aberdeen recently, oil and gas operators in the North Sea simply don’t do enough such work and also don’t get the most out of their existing intervention work.

Vasquez pointed out that with $50/bbl oil having resulted in operators becoming significantly cash-constrained and with reduced budgets, production and ultimate recovery targets still remain. Well intervention will simply help lower operating expenses per barrel. “It also is usually cheaper, quicker and less risky—and yields higher returns per barrel than drilling a new well,” she said. “The incremental volume and recovery opportunity is significant; most active operators realize over 10% incremental production and 5% barrels protection from well intervention. However, operators don’t do enough intervention and fail to get the most from their intervention efforts.” The 5% barrels protection involves insuring a well’s production level within 5% of its present level to protect against rapid decline.

Vasquez questioned why not enough well intervention work is being carried out, concluding that asset managers tend to put a lower priority on well integrity and production optimization tasks to protect production levels. “The belief is that drilling brings higher value. Asset teams lack the information to be certain that intervention will bring higher value than drilling.”

Vasquez added that there also was a failure to get the most from intervention activity, for reasons including a shortage of good opportunities, companies preferring not to take a risk and also companies simply not knowing whether an intervention had worked by not fully understanding intervention performance.

Back to the future

The above actions are early evidence that the U.K. industry is tackling the daunting task of raising its game operationally and economically with its usual application.

Although too soon to be able to predict success with any certainty, its track record earned during the past five decades of offshore achievement would infer that it is capable of once more rising to the challenge.

Perhaps one of the most significant illustrations of the U.K. offshore sector’s undoubtedly innovative culture—and its ability to leave no stone unturned—during such a historic anniversary year is one that features the very first producing field that started it all.

Argyll reborn—again

The Argyll Field is due to start flowing oil again this year, 40 years after producing its first pioneering barrels.

EnQuest is redeveloping the field, now known as Alma, located in the central North Sea in U.K. blocks 30/24 and 30/25. Lying in a water depth of 80 m (262 ft), this redevelopment project is expected to see production flow for up to 10 years. With estimated recoverable reserves of more than 20 MMbbl of oil, and possibly up to 32 MMbbl, the field is expected to produce around 4.5 MMbbl of oil during its first year.

As Argyll, it produced more than 72 MMbbl of light sweet crude during a 17-year period before being decommissioned in the early 1990s.

Incredibly, this is not the first time Argyll has been redeveloped but the second, having been produced under the name Ardmore via two wells for two years using the modified Rowan Gorilla VII jackup rig by operator Tuscan Energy. It produced more than 5 MMbbl of oil before being decommissioned again in 2008, having been deemed uncommercial at that time.

EnQuest decided to redevelop the marginal field in late 2011, along with the nearby Galia satellite discovery, with water injection and electric submersible pumps to be used to help produce the now-low-pressure reservoir.

The wells will be connected to an FPSO vessel, Bluewater’s upgraded floater formerly known as Uisge Gorm and now called the EnQuest Producer, through 10-in. flowlines. Moored on location over the field in May, the preparation process is almost complete, with first oil expected imminently via five wells.

In many ways Argyll—or Alma, as it is called now—is truly representative of the U.K. offshore scene. Discovered more than four decades ago, it produced, peaked, matured, declined and was then written off. A decade later it went through a smaller-scale revival, produced at a lower level and was then written off once more.

But here we are, in the next decade, and there’s still apparently plenty of life (and dollars) in the old girl yet. A shining microcosm, perhaps, for the UKCS as a whole.

Small Fish, Big Prize

The U.K. is targeting the development of approximately 287 “small pools” of hydrocarbons on the U.K. Continental Shelf (UKCS) as a means of maximizing the recovery of oil and gas left in the ground as well as acting as a trigger for further technology innovation and development.

Gordon Drummond, project director at the National Subsea Research Initiative (NSRI), told delegates at a recent conference in northeast England that this would help sustain the U.K. subsea industry in particular. He sees the pursuit of small pools as the next step, defining them as reservoirs of between 3 MMboe and 15 MMboe. He added that to achieve production from these assets, the industry must create new technology.

Operators Centrica and EnQuest are acting as technology champions for this “small pool” push, with workshops to be held in Aberdeen, Newcastle and London to pursue such projects.

“Small pools are a positive story about chasing new reserves and not the start of the decommissioning process for the U.K.,” he said.

Paddy O’Brien, CEO of the Industry Technology Facilitator (ITF), added that the Centrica- and EnQuest-backed project is looking to develop reserve pools of either 10 MMboe of gas or 30 MMboe for less than US$156 million (£100 million). “How technology can reduce costs will figure highly in the current climate,” he said.

Jeremy Cutler, Total E&P U.K.’s head of technology innovation, said his company’s target for small pools in the U.K. is to develop 15 MMboe for less than US$234 million (£150 million).

Total has three main U.K. technology focus areas: long-distance subsea tiebacks (small pools), effective drilling and completions (lower costs/increase productivity), and intelligent operating and maintenance (including the use of robotics for unmanned platforms).

Others include subsurface imaging, decommissioning and onshore shale gas, Cutler added.

Analyst Wood Mackenzie has estimated that there are currently more than 300 discoveries without development plans containing nearly 3.9 Bboe offshore the U.K. The last time a discovery larger than 100 MMboe was made in traditional sandstone reservoirs was in 2008 when the Culzean Field was found.

Recommended Reading

Devon, BPX to End Legacy Eagle Ford JV After 15 Years

2025-02-18 - The move to dissolve the Devon-BPX joint venture ends a 15-year drilling partnership originally structured by Petrohawk and GeoSouthern, early trailblazers in the Eagle Ford Shale.

E&P Highlights: Feb. 18, 2025

2025-02-18 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, from new activity in the Búzios field offshore Brazil to new production in the Mediterranean.

Baker Hughes: US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for Third Week in a Row

2025-02-14 - U.S. energy firms added oil and natural gas rigs for a third week in a row for the first time since December 2023.

Exxon Seeks Permit for its Eighth Oil, Gas Project in Guyana as Output Rises

2025-02-12 - A consortium led by Exxon Mobil has requested environmental permits from Guyana for its eighth project, the first that will generate gas not linked to oil production.

VoltaGrid to Supply Vantage Data Centers with 1 GW of Powergen Capacity

2025-02-12 - Vantage Data Centers has tapped VoltaGrid for 1 gigawatt of power generation capacity across its North American hyperscale data center portfolio.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.