(Source: Shutterstock)

Comstock Resources and Aethon Energy’s wildcat western Haynesville, or “Waynesville,” average full-month daily production increased in June without adding new wells, according to Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) data.

Comstock reported this summer that it had been loosening up some chokes after coming to better understand the more than 2-year-old play’s super-high-pressure regime in the area.

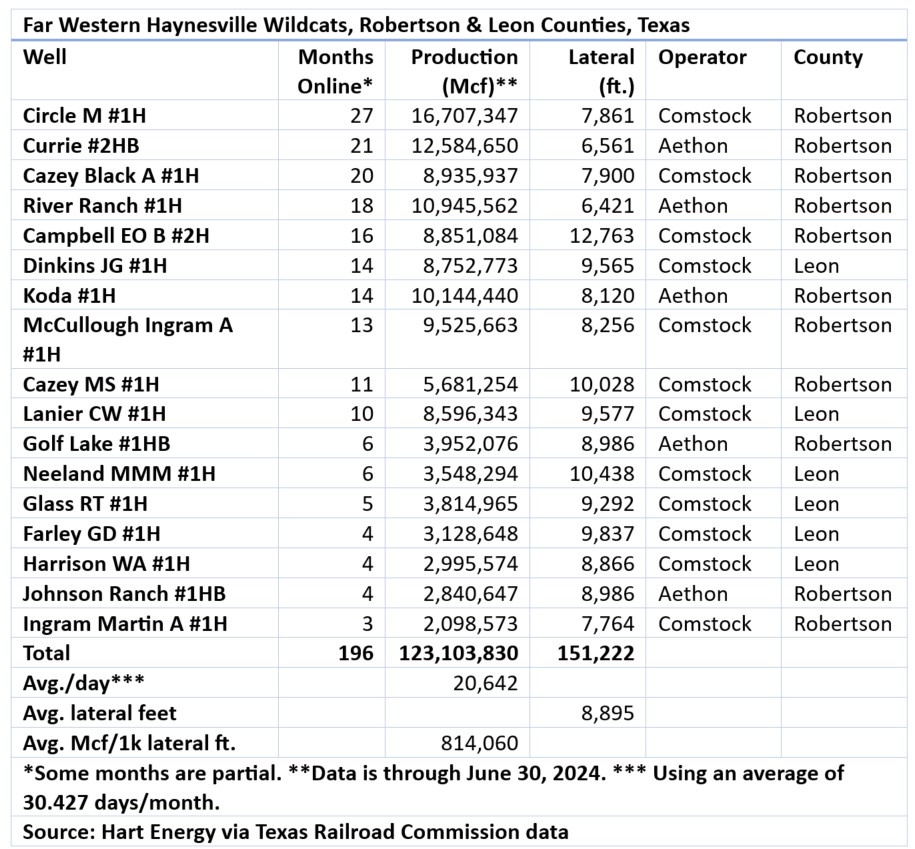

Production from the total 17 wells—online between 27 months and three months—through June averaged 20.642 MMcf/d, up from 20.635 MMcf/d through May.

The horizontals, all in Robertson and Leon counties, Texas, north of Houston, have averaged 814 MMcf per 1,000 lateral feet in their combined 196 months online, according to the data.

Twelve are producing for Comstock; five are online for Aethon.

Altogether, they have produced 123.1 Bcf of gas from roughly two-mile laterals landed in the Late Jurassic, deep, high-pressure, high-temperature Bossier and Haynesville formations.

The newest well—Comstock’s Ingram Martin A #1H—has made 2.1 Bcf its first three months online from a 7,764-ft lateral in Robertson County.

The oldest well—Comstock’s Circle M #1H—produced 16.7 Bcf through June in 27 months online. To date, its output has averaged 2.13 Bcf per 1,000 lateral feet.

Among the 12 Comstock wells, six are in the Haynesville and six in the Bossier.

Testing spacing

Comstock is testing spacing now in its more than 450,000 net acres in the two counties, with two 2-well pads drilled this summer. These will be completed in the fourth quarter and come online by year-end or in early January, according to Comstock.

In addition, it expects to have two more singles—Hodges RLT #1H and Miles BM #1H, both in Leon County—online at that time as well.

One of the two 2-mile pad wells took 54 days to drill; the other, 56 days.

Comstock’s first single wells in the play each took 85 days to drill, while the target formations are at up to 19,000 ft in vertical depth and the laterals averaged 2 miles.

Jay Allison, Comstock chairman and CEO, told investors in a call this summer, “We spent a lot of money putting together this world-class footprint in the western Haynesville. And now we just want to de-risk it, well by well.”

Dan Harrison, COO, added, “We have a lot more money in a Western Haynesville well, but we have a lot more reserves. I mean, the reserves are double.”

Science-ing

Comstock is still science-ing the play to a degree, Harrison added.

“It’s a different type of play. The declines are different. We’re still trying to figure out how to produce the western Haynesville wells.”

Traditional Haynesville wells in northeast Texas and northwestern Louisiana might produce more in their first six months. But Comstock’s been choking back the western Haynesville wells, which are producing more in subsequent months.

“We started off in the western Haynesville being much more conservative with how we were producing the wells,” Harrison said.

In the traditional Haynesville, “we know … how hard we can pull them.

“But in the western Haynesville, we're just on the tip of that learning curve. So we started out very conservative, very low drawdowns,” Harrison said.

More recently, Comstock has loosened chokes some. “We just want to watch the drawdowns and make sure we don't get ahead of ourselves as far as trying to pull them too hard,” he said.

“But everything looks really good. We're just kind of taking our time in that process.”

Comstock is also flowing the wells up tubing when they’re turned into sales, unlike traditional Haynesville wells where Comstock may return a couple of years later and tube the wells, Harrison said.

This is “just because of the very high initial flowing pressures … on our casing strings,” he said. “We tube those up while we're completing the well.”

It results in a different production profile, he said.

“You get a lot more pressure drop downhole before you reach the surface. So the pressures obviously would be a lot higher if we were flowing up casing.”

Recommended Reading

Not Sweating DeepSeek: Exxon, Chevron Plow Ahead on Data Center Power

2025-02-02 - The launch of the energy-efficient DeepSeek chatbot roiled tech and power markets in late January. But supermajors Exxon Mobil and Chevron continue to field intense demand for data-center power supply, driven by AI technology customers.

BlackRock CEO: US Headed for More Inflation in Short Term

2025-03-11 - AI is likely to cause a period of deflation, Larry Fink, founder and CEO of the investment giant BlackRock, said at CERAWeek.

Transocean President, COO to Assume CEO Position in 2Q25

2025-02-19 - Transocean Ltd. announced a CEO succession plan on Feb. 18 in which President and COO Keelan Adamson will take the reins of the company as its chief executive in the second quarter of 2025.

Ovintiv Names Terri King as Independent Board Member

2025-01-28 - Ovintiv Inc. has named former ConocoPhillips Chief Commercial Officer Terri King as a new independent member of its board of directors effective Jan. 31.

Independence Contract Drilling Emerges from Chapter 11 Bankruptcy

2025-01-21 - Independence Contract Drilling eliminated more than $197 million of convertible debt in the restructuring process.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.