It’s August now, so the Permian’s oil pipelines must be completely full. In June, they were at 95% of capacity. Analysts expect it to get worse before it gets better, with options on non-basis-hedged, Permian-weighted producers’ shares seeing maximum pain around year-end.

Why was anyone surprised? “Yeah,” said Subash Chandra, managing director and senior equity analyst for Guggenheim Securities LLC. The equity market was focused on the upcoming gas takeaway bottleneck out of the Permian, which, according to several analysts’ estimates, is happening right about now as well.

And publicly held producers’ combined guidance in fourth-quarter 2017 on their increased Permian oil output for 2018—if combined with increased output by private operators—wasn’t being given as much investment-market attention.

“I think some operators also thought that way,” Chandra said. “They didn’t think the overall group would be able to generate such high amounts of oil growth out of the basin in calendar year ’18. The mindset, if you recall, was the U.S. supply-growth numbers are too strong. They’re artificial. They’re going to get revised down. It can’t be happening.’

“And, then, it became one of no revisions [after all]. In fact, the possibility of upward revisions to U.S. oil-supply growth is very strong. ‘There is no end in sight.’ That happened fairly quickly,” Chandra said.

So operator A didn’t think operators B-Z would actually show up? And B didn’t think C-Z would show up? “Yes, and the privates, the PE-backed, the integrateds, right? So I think, by the first quarter, it became clear U.S. oil supply growth was not going to be de-rated in any way.”

Production phenom

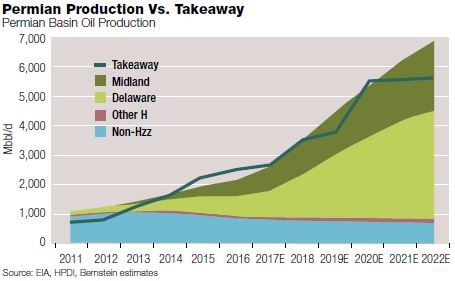

In the first half of 2017, Michael Hanson posed a question: “What if everyone does what they say they will do?” At the time, Permian output was 2.2 million barrels per day (MMbbl/d). Hanson, a founding member of investment banker Parkman Whaling LLC, went to work on the math. The results: Mid-2018 Permian production would be at least 3.2 MMbbl/d.

In late June, Permian production was 3.2 MMbbl/d. At the same time, Permian takeaway and in-basin refining capacity was about 3.2 MMbbl/d.

Jean Ann Salisbury, senior analyst for Bernstein Research, and colleagues Bob Brackett and Dave Vernon gathered some slides in late May to explain the phenomenon to investors and hedgers. Salisbury said, “We had expected this [would appear] in the second half of 2018—that you would outpace pipeline capacity—but it happened a bit earlier than we thought for a couple of reasons.”

One of her charts showed the number of new Permian wells. “But, more importantly,” in the other chart, “you can see that the average well in the Permian just keeps getting better,” Salisbury said.

Recent results include two Devon Energy Corp. wells in its Boundary Raider development in the Delaware Basin. These IPed earlier this year with a combined 24,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day (boe/d), 80% oil. John Raines, Devon vice president, Delaware Basin business unit, said at Hart Energy’s DUG Permian conference in May that the company may have two more company-record Delaware wells.

As for EOG Resources Inc., J.P. Morgan Securities LLC analysts wrote in a note that the producer’s Convoy-pad results in New Mexico “rival” Devon’s Boundary Raiders, which, they added, “are clearly the best wells in the history of the Delaware Basin.” EOG’s six Convoy wells averaged some 5,600 boe/d, 76% oil, for a combined 33,000 boe/d from completions in May.

In summarizing the Permian’s oil potential, Bill Marko, managing director for Jefferies LLC, pointed to a 20,000-acre development in the northern Delaware, for example. “This is why the Permian really matters,” he told members of the M&A group ADAM-Houston this summer.

“On current spacing, the recovery factor is 3.2%,” he said. “If you talk about really tight well spacing and being able to produce all nine benches, you’ve got a 17.6% recovery factor [with original oil in place of 29.3 billion—yes, billion—barrels]. …This is why everyone is so excited about the Permian.”

Flashpoints

Bernstein’s Salisbury, in her client call, said that, while the market may have been expecting 3.2 MMbbl/d from the basin in the latter part of this year, there isn’t significant takeaway scheduled to come online until 2019. “E&P didn’t really underwrite new pipelines for all of 2017.”

KeyBanc Capital Markets Inc. analyst David Deckelbaum noted that this has happened before in this new century of Permian production: “Throughout early 2015, the Midland differential was over $10/bbl as production exceeded takeaway capacity and began to narrow down in [the second half of 2015] as capacity expansions kicked in.”

In early June, Brent was +$10/bbl to West Texas Intermediate (WTI) Cushing, and WTI Midland was -$12/bbl to WTI Cushing. “Midland is a whopping $22/bbl off Brent,” Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. (TPH) analysts summarized.

How bad is it? Greg Haas, director of integrated oil and gas for research firm Stratas Advisors, told clients, “It’s so bad that the sour and sweet WTI grades at Midland are nearly priced at parity.”

And there’s more: “It’s so bad that light WTI Midland costs significantly less than heavy sour crude delivered from Mexico—$62.90/bbl—at the U.S. Gulf Coast. It’s so bad that Midland light sweet crude is underperforming the light syncrude—$63.79/bbl—manufactured up in Canada.

“The only good news for WTI Midland is that at least it is outperforming the price of heavy Canadian Select crude—WCS, $42.04/bbl—for now, but, a few days ago, we saw intraday prices for WTI Midland and WCS at parity.”

The WTI Midland (Argus) vs. WTI futures on Nymex in late June had Midland at more than -$6 into August 2019 and as much as -$14.48 this October. WTI Cushing itself was $69, propped by an OPEC decision to not increase output beyond its existing quota. Brent was $75.

Several analysts estimate that most Permian producers’ flashpoints are at below $50/bbl. R.T. Dukes, research director of U.S. Lower 48 upstream for Wood Mackenzie, tweeted, “If my Monday morning eyes are seeing it right, Midland WTI futures no longer fall below $50 per barrel. That’s an important threshold for planning and sentiment in the Permian Basin.”

DUCing

What will this second half and into 2019 look like? KeyBanc’s Deckelbaum titled and subtitled his summary with lyrics from a 1970s ballad that isn’t identified here because it might evoke a most unwelcomed earworm. He dropped the “max pain” bomb—besides having already prompted mind pain—in describing where this is headed.

In max pain, the greatest number of options, in dollar value, will expire worthless. On a SUDS (subjective units of distress) scale, that would be a 10—unbearably bad. The Mid-Cush differential had been just -$0.40/bbl in January.

Deckelbaum had expected in June that every cubic inch of big-pipe takeaway would be in use by now. Further phenomena may include converting water hauling trucks into oil hauling trucks, putting further pain on operators that don’t have their water on pipe, Deckelbaum added.

Those in-basin water hauling trucks might not be in as much demand, though. The Barclays Capital Inc. team expects Permian DUC (drilled, but uncompleted, well) builds and/or operators spending in other basins until the additional pipes arrive.

The EIA estimates some 3,200 DUCs in the basin—roughly twice as many as a year ago. Deckelbaum estimates the top oil-play beneficiaries of redirected spend will be the Eagle Ford and Bakken as that oil has sufficient direct routes to Gulf Coast pricing.

There is also rail, but Ethan Bellamy, senior research analyst for R.W. Baird & Co. Inc., said, after Plains All American Pipeline LP’s analyst day in early June, that truck and rail options are limited. “Plains estimates 150,000 bbl/d of total truck and rail capacity, which won’t add materially to Midland and Delaware takeaway capacity.”

TPH analysts took a look at the truck option in early May. Training to receive the proper license is up to 10 weeks, so labor availability is possible—“at a cost.” But mandatory trucker electronic logging went into effect in December and enforcement began in April.

“Lastly,” TPH reported, “the average [truck] tanker holds some 9,000 gallons—or some 215 barrels. That means 100,000 bbl/d by road takes 1,000-plus trucks—factoring in travel time to and from the Gulf Coast along with driver-resting rules.”

Defer?

Guggenheim’s Chandra said that adding basis hedges for the balance of this year and into 2019 isn’t really possible now for producers. “I think the market conditions have gotten away from them. In other words, if they attempted to basis hedge now, it would be pretty expensive. I think the opportunity is gone.”

Instead, exposed Permian producers’ other opportunity is “slowing your program down. Just tell people that, ‘We can defer this program and we can restart this program without a whole lot of friction or time lapse. If we do that, we spare ourselves one year of trauma and volatility. We come out on the other side and we can recapture and sell our oil for a lot more without locking ourselves into anything.’”

He added, “Which could be what Halcón [Resources Corp.] is trying to message today.”

Delaware Basin pure-play Halcón announced in mid-June that it was dropping one of its four rigs. It expects to have firm transport of 25,000 bbl/d to the Gulf Coast by the second half of 2019. In April, it sold in-the-money basis hedges for some $30 million.

That and some ongoing Mid-Cush hedges mean its discount to WTI is $3.90/bbl on 8,000 bbl/d in this half and a $0.03/bbl premium on 12,000 bbl/d in the first half of 2019.

TPH analysts called the Halcón (“hawk” en espanol) news “El Canario in the Coal Mine,” adding, “… This falls in line with our thinking from last week that privates and smaller operators in the basin are most likely to feel the pressure from a pricing standpoint.”

In client calls in early June, the analysts found both long-only and hedge fund clients “are now generally convinced that [Permian] activity cuts are a matter of ‘when,’ not ‘if.’” They’re staying on the sidelines, meanwhile.”

The team expected more news like Halcón’s “as we believe Midland differentials have the potential to get worse before they get better in the fourth quarter of 2019 and first quarter of 2020, when Midland-Gulf Coast lines come online.”

J.P. Morgan’s oil and gas analysts estimated that operators without firm transportation (FT) “may have to at least consider the idea of deferring completions if the basis in fact blows out past a $15 to $20/bbl differential for a considerable period of time or if physical constraints become reality.”

Chandra said, “The initial concern is folks don’t want to lower their production numbers for ’18 or ’19. But, if they can just explain that one year of deferral doesn’t cost you much in terms of valuation—in fact, what you lose on time, you more than gain on pricing—it’s not a terrible message. I think if you put in the right slides and show the math, folks will get it.”

Less is more? “Yeah, at least for a short period of time. If you truly believe this is a short-term issue and the pipes are coming, which they are, the question becomes how much of a delay there could be in those pipes coming on. But the pipes are coming on.

“If you believe it is going to get worse before it gets better, but the whole span of this event is a year, then defer. And, if what you get on the other side of that is $4 or $5 per barrel or better, I think the market would be like ‘Cool’ vs. saying, ‘Hey, we’re going to basis-hedge our way through this and lock ourselves into these hedges—and these hedges are increasingly expensive, so we’re locking ourselves into worse pricing. But we’re doing it because we just don’t want to show less volume.’

“For optics, you’re paying a price. It’s better to make an economic decision. Now, if they look at it internally and find that ‘If deferring production, we lose efficiencies in X, Y and Z’ and, if the efficiencies lost are overwhelming, then I would understand. They need to convey that.

“But, if it’s just to preserve optics, which is consensus production—‘We’ve got to get to X. We don’t want to disappoint on that number even if it means we’re selling oil for a lot lower prices or tying this company up for longer than we need to into a crappy market’—that makes no sense.”

Exiting 2017, the Permian rig count was 398, three times the 132 of April 2016, according to Baker Hughes, a GE company. On June 22, it was 473.

Capital One Securities Inc. analysts estimated a drop in the count might look like this: The rigs go to the Eagle Ford and other basins with stronger netbacks. Some wells are DUCed. Some oil capacity may be put in trucks and on rail. A worst case is the count drops 25% or some 120 rigs, “however,” they added, “that’s a bit draconian.”

Baird analysts wrote after pipeline operator Plains’ analyst day, “Plains anticipates shut-in and/or foregone production growth in the Permian Basin to persist through 2020.”

As for operators slowing down, Imperial Capital LLC senior analyst Irene Haas reported, “So far, public companies we speak with have no plan to change their development plans for 2018. … Private companies could be more susceptible to pulling back due to a lack of scale and internal expertise in the marketing and hedging arenas.”

The hedged

Devon has Midland swaps on 23,000 bbl/d at -$1.02 to Cushing this year and on 28,000 bbl/d at -$0.46 in 2019. J.P. Morgan analyst Arun Jayaram reported that “Devon does not anticipate slowing down its activity in the Delaware Basin as basis swaps and firm transport protects some 90% of its oil volumes from a margin perspective.”

Guggenheim’s Chandra told Investor that, within his coverage universe, the leading basis-hedged Permian producers are, in this order, Concho Resources Inc., SM Energy Co., Jagged Peak Energy Inc., Energen Corp., Matador Resources Co., Carrizo Oil & Gas Inc., QEP Resources Inc. and Encana Corp. At average is Centennial Resource Development Inc.

“So Centennial is at half the basis hedges of a Concho, SM and Jagged Peak. There is a pretty wide disparity.”

That’s for 2018. “The problem is, by the time you get to 2019, everyone is overwhelmingly under-hedged on basis.”

Energen’s April-December 2018 Mid-Cush hedges on 9.2 MMbbl—about 58% of midpoint-guidance production in that timeframe—are at an average of -$1.37/bbl. Julie Ryland, Energen vice president, investor relations, told Investor, “Assuming the differential for this time period is actually -$10/bbl, the hedges would represent pre-tax savings on these volumes of approximately $80 million.”

Energen also has -$1.11 Mid-Cush hedges on 6.8 MMbbl in 2019 and, Ryland said, “The company continues to look for opportunities to add to its 2019 hedge position.”

SM has roughly -$1 basis swaps on about 70% of its Permian production through year-end. Next year, swaps are on about 50% of production at up to -$4.49. It reported in late June that it didn’t expect to change its $1.27-billion 2018 capex plan.

Jay Ottoson, president and CEO, told shareholders, “For context, if actual market differentials are -$15/bbl through the second half of 2018 and 2019, our expected realized differential on total Midland oil production, net of hedges, would be approximately -$5/bbl for the second half of 2018 and -$8.50/bbl in 2019.

Among small and mid-caps TPH covers, the team cited WPX Energy Inc., PDC Energy Inc., Parsley Energy Inc., Encana and Diamondback Energy Inc. as “best positioned in our coverage to weather the storm in 2019.”

KeyBanc’s Deckelbaum liked Parsley, Oasis Petroleum Inc. and Pioneer Natural Resources Co. Yet, he warned: “While we believe Permian challenges may be temporary, being selective has never been more critical.”

Getting Brent

Bernstein’s Brackett named Pioneer as “furthest ahead of the bunch. For quarter-after-quarter now, we have heard Pioneer talk about how many cargos they exported. It seemed kind of cutesy and less relevant four or five quarters ago.

“Now it’s clearly a source of competitive advantage where they’re delivering 160,000 bbl/d of the Permian straight to the Gulf Coast, exporting about half of it and getting Gulf Coast refinery prices for the other half.”

According to Pioneer, its exported portion is expected to grow in this half from 110,000 bbl/d to 150,000.

Capital One Securities Inc. E&P analysts wrote, “Pioneer looks to have the most advantaged marketing position out of any Permian producer, as far as we can tell.” Having firm transport to the Gulf Coast, “the vast majority of [its] barrels are getting premium pricing to WTI rather than a noticeable discount.”

Its firm transport to the Gulf is on more than 90% of its expected production through 2021. “We are not aware of any other Permian producer that can make such an emphatically positive claim,” they added.

KeyBanc’s Deckelbaum added that Parsley is getting a third of its production to the Gulf and PDC “has tied most of its Delaware crude volumes to the Gulf Coast as well.”

Seaport Global Securities LLC (SGS) analysts found that PDC’s “takeaway position is more favorable than widely understood.” Its contracts have 85% of its Delaware output going to the Gulf Coast this and next year.

“ … We believe many may have underappreciated how insulated the company will be as Mid-Cush diffs take their toll on the Permian-levered group.”

The SGS team noted that Diamondback bought some firm transport in mid-June to switch from none of its oil on contract to 66% in this half, 70% in 2019 and 100% in 2020. “In order to make this happen, Diamondback gets dinged with a hefty transport/marketing fee over the next two years,” they added.

Under the contracts, Diamondback’s average discount to the Gulf Coast price is between $14 and $17/bbl. In 2019, it’s between $10 and $12; in 2020, $5. The SGS analysts estimate a net effect on Diamondback’s EBITDA of some 8% less for this half and some 4% less in 2019, but some 4% greater in 2020.

Implications for M&A

Jefferies’ Marko told Investor the basis situation in the basin may chill M&A activity there. “I think it will mean lower valuations because people are going to grind those [differentials] in. Certainly, the buyers are going to grind those in. And I think it will make the sellers reluctant to sell because they don’t want to be schmucks who sell now and, in a year, it gets cleaned up and they’ve lost $15 a barrel.

“Any time there is uncertainty and risk, it chills things a bit. I think it’s just another bit of a headwind into the amount of deals we see.”

Bernstein’s Brackett told clients in May, “If valuations were to be punished enough, look at it as a tool for industry consolidation. We’ve talked about that previously—that there is a scale that matters in the Permian: the ability to run enough rigs, ability to be able to call Halliburton [Co.] and secure a frack fleet, the ability to be an anchor on a pipeline takeaway project.

“So,” Brackett continued, “this congestion in the Permian might have the unintended consequence of consolidating the basin and actually making it stronger on the way out. In that case, we would be interested in any stocks that are overly punished for what ultimately should be a multi-quarter misstep as opposed to a long-term net-asset-value story.”

Capital One Securities analysts reported in early June, after visiting with E&Ps in Houston, that Permian takeaway and WTI Midland differentials “are currently, by far, the biggest themes/concerns in the E&P space.” They estimate a “likelihood for companies to expand activity and/or acreage positions outside the Permian, given takeaway constraints.”

SGS reported it was seeing interest in Eagle Ford- and Bakken-weighted stocks. An operator in the former, Lonestar Resources US Inc.’s “exposure to premium Gulf Coast pricing looks extremely hard to resist, given the near-term [Gulf] LLS-Midland spread.” At the time, the second-half 2018 spread was more than $18.

In the Bakken, SGS cited Whiting Petroleum Corp. “A Bakken-levered E&P provides safe haven from Permian differentials and exposure to one of the highest rate of change plays in the Lower 48.”

Where’s the pipe?

This pipe-short situation in the basin has appeared before. In this century, until 2013, Permian production was less than 1 MMbbl/d, according to the University of Texas of the Permian Basin (UTPB). About half of that is used in-basin, equity analysts estimate. In the 1970s, at its peak, the basin produced about 2 MMbbl/d, according to UTPB.

2013 began with a Mid-Cush differential of -$14. In August of 2014, it was -$21.

Without takeaway or other above-surface constraint, KeyBanc’s Deckelbaum expects Permian production of 4.9 MMbbl/d by 2022.

Hanson at Parkman Whaling forecasted in the first half of 2017 that it will get there sooner, when answering the “What if everyone does what they say they will do” question. By January 2021, Permian production will be between 4.5 and 5.3 MMbbl/d, according to his calculation.

In Hanson’s analysis, what was needed—capital, equipment, materials, people, low or no cost inflation, an improved commodity price, takeaway—to reach the 3.2 MMbbl/d that he forecasted would be seen this summer was tremendous, suggesting the mark wouldn’t be reached.

But it was reached.

Announced new takeaway underway, according to Imperial’s Haas, would bring capacity by year-end 2019 to more than 5 MMbbl/d, “which should be more than enough to accommodate the expected production—and growth—in 2019 and 2020, in our opinion,” she reported.

The leading projects are Cactus II (585,000 bbl/d) to Corpus Christi/Ingleside with a third-quarter 2019 completion; EPIC (590,000 bbl/d with 440,000 of those from the Permian) to Corpus Christi, second-half 2019; Gray Oak (up to 700,000 bbl/d) to Corpus Christi and Sweeny/Freeport, year-end 2019; and an Enterprise NGL-to-oil conversion (200,000 bbl/d) to the Gulf Coast, 2019.

ExxonMobil Corp. and Plains surprised the market in mid-June with news of a letter of intent to partner in a 1-MMbbl/d pipe to the Houston Ship Channel and Beaumont. TPH analysts reported that, with this news, the conversation about Permian oil bottlenecks is “quickly shifting … to a 2020-plus overbuild scenario.”

SunTrust Robinson Humphrey midstream analyst Tristan Richardson estimated that, “although the announcement is purely an LOI at this point” a timeline of a year-end 2018 investment decision would have the pipe in service in mid-2020 at the earliest.

“Given this is a producer-backed project—for all practical purposes, even if this producer is massive and is also a refiner—we expect the project timeline will be more dictated by ExxonMobil’s development plans than the overall needs of the basin and, as such, may not be some ‘race to market’ type of endeavor.”

Meanwhile, why is Cushing pricing for WTI still relevant when more and more WTI is going to the Gulf Coast? Reuters took up the topic in April. Carlin Conner, SemGroup Corp. CEO, said, “I believe Cushing’s next chapter is that it’s going to become an offsite Gulf Coast storage center.”

Cushing’s reign as the Nymex trading price for WTI was borne from the 1980s launch of Nymex WTI futures trading during the U.S. crude export ban that ended in late 2015.

TPH analysts reported in early June that, with further Permian takeaway projects directed to the Gulf Coast, “we believe Permian operators will cease flowing barrels to Cushing in favor of better priced, export-linked markets.”

Bernstein analysts expect the upcoming new round of big-pipe additions will get the Permian only into mid-2020, when there will be another shortfall at the current rate of production growth.

Imperial’s Haas wrote after the ExxonMobil-Plains news, “Permian outbound congestion is real, but we believe the market has overreacted.” She anticipates WTI relief will come in early 2019.

“Texas is a mature petroleum province crisscrossed by a dense network of pipelines, some of which can be repurposed, reactivated and upgraded within short time periods.”

That natgas

Adding to the Mid-Cush equation is associated-gas production. Permian producers are expected to capture associated-gas production, and that takeaway capacity is also full.

TPH analysts estimated that the “gas wall likely hits at a similar time to crude—late 2018 into early 2019—and could prove an equal barrier to growth as increased flaring may draw additional regulatory and environmental scrutiny.”

KeyBanc’s Deckelbaum is less concerned. “We view natural gas as less of an issue as the region does not have basin-wide regulation on absolute flaring volumes. Rather, restrictions are granted at the lease level during what is the most sensitive production timeframe—initial production.”

Meanwhile, Baird analysts drew a different conclusion: “The fate of Permian oil this summer looks set to come down to the [Texas Railroad Commission (RRC)]. Natural gas export capacity is maxed out.

“To keep the oil flowing, producers will need to flare, find excess capacity elsewhere or shut in production. Producers can receive a 45-day permit from the [RRC] to flare gas for a maximum of 180 days, primarily for casinghead gas. … Rare exceptions for long-term flaring may be made in cases where the well or compressor is in need of repair.”

SunTrust upstream analyst Neal Dingmann wrote that the RRC “plays ball, but the New Mexico Oil Conservation Division may not.” Many Permian producers have gas takeaway contracts, but “several companies have nothing firm.”

He expects Texas “will allow mostly all needed Permian natural gas flaring,” but New Mexico won’t. “This would be pressure on the northern Delaware Basin operators.”

Imperial’s Haas reported, “Natural gas transport capacity is tight, but most of the public companies under our coverage have secured outbound transportation arrangements and will have flow assurance, in our opinion.

“However, companies will still take varying degrees of revenue hit, as it is difficult to hedge for Permian-gas basis differentials. We believe that smaller, private E&Ps might become ‘swing producers,’ opting to slow down with unfavorable differentials and help ease the congestion, and more related consolidations could be on the horizon.”

Recommended Reading

Exxon, Chevron Beat 3Q Estimates, Output Boosts Results

2024-11-01 - Oil giants Chevron and Exxon Mobil reported mixed results for the third quarter, with both companies surpassing Wall Street expectations despite facing different challenges.

EON Enters Funding Arrangement for Permian Well Completions

2024-12-02 - EON Resources, formerly HNR Acquisition, is securing funds to develop 45 wells on its 13,700 leasehold acres in Eddy County, New Mexico.

ConocoPhillips Hits Permian, Eagle Ford Records as Marathon Closing Nears

2024-11-01 - ConocoPhillips anticipates closing its $17.1 billion acquisition of Marathon Oil before year-end, adding assets in the Eagle Ford, the Bakken and the Permian Basin.

Marathon Oil Expects ‘Mass Layoff’ After ConocoPhillips Deal Closes

2024-10-31 - Marathon Oil’s merger with ConocoPhillips, which is to close by year-end, will trigger a layoff of more than 500 Houston employees, according to a state regulatory filing.

Dividends Declared Weeks of Nov. 25, Dec. 2

2024-12-06 - Here is a compilation of dividends declared from select upstream and midstream companies in fourth-quarter 2024.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.