The analyst said there are plenty of growth opportunities in the sector in the coming years, as natural gas demand is expected to dramatically increase for the rest of the decade. (Source: Shutterstock)

SAN ANTONIO, Tex. — Some much-needed natural gas egress capacity is coming to the Permian Basin soon, but one analyst pointed out Sept. 23 that, so far, the gas isn’t going to the most logical (or profitable) place.

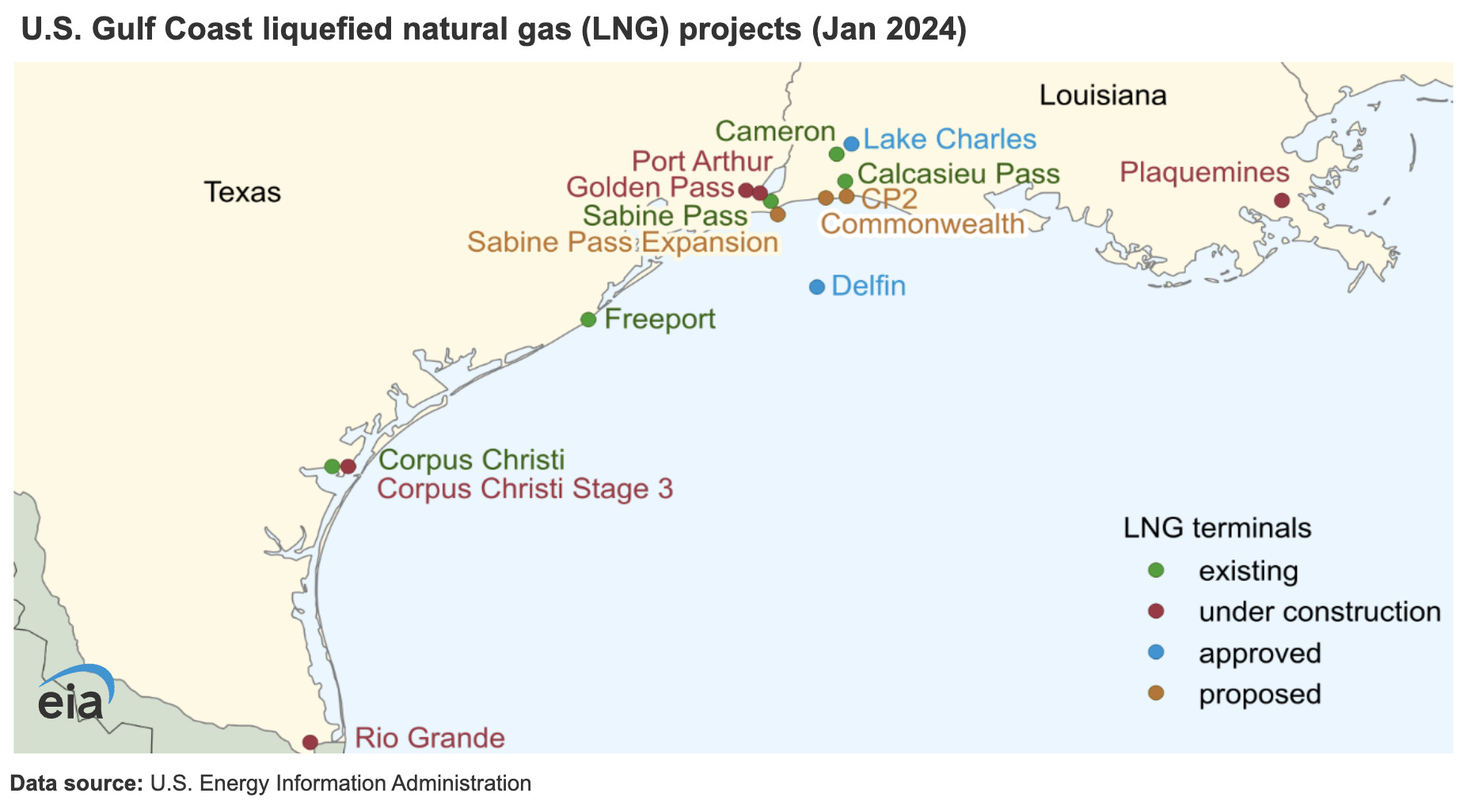

Connor McLean, senior energy analyst with FactSet, noted at the GPA Midstream Convention that the two major U.S. natural gas pipelines expected to come online over the next two years are not headed to the center of U.S. LNG production.

“Permian pipelines are not reaching where LNG demand is,” McLean said. “LNG demand is concentrated mostly in Southeast Texas and Southwest Louisiana.”

McLean spoke during the opening session of the GPA conference, addressing the topic of “Risks and Opportunities in U.S. Natural Gas Midstream.” The analyst said there are plenty of growth opportunities in the sector in the coming years, as natural gas demand is expected to dramatically increase for the rest of the decade to meet the increasing needs of the U.S. power sector and LNG exports.

However, building out the infrastructure remains difficult in a market that faces plenty of regulatory and logistical hurdles.

In the Permian Basin, producers have focused primarily on getting the natural gas out of the region. The Midland and Delaware basins are focused on crude production; gas is an unwanted byproduct. Egress out of the region has been full for a year and natural gas has suffered negative pricing for most of the summer.

McLean pointed out that the two pipelines slated for the region will fill rapidly, with the gas delivered to markets that are also close to capacity.

Whitewater’s Matterhorn Express pipeline is in the startup process and will carry about 2.5 Bcf/d of natural gas to the Houston market. The recently announced Blackcomb pipeline, which will deliver natural gas to South Texas, is slated to begin operations in 2026.

Both regions have one LNG liquefication facility each (Freeport and Cheniere’s Corpus Christi Lsite). The hub of U.S. LNG production is farther east, on the Texas-Louisiana border, with three LNG facilities operational and another two under construction.

“We have approximately 1.5 Bcf/d of space on existing interstate pipelines between Texas and Louisiana. As recently as 2023, it’s been quite full,” McLean said.

Some cross-border capacity has opened up since then, but not enough to handle the extra natural gas from the Matterhorn Express coming online; not to mention the Blackcomb in 2026.

Some other projects are underway that will increase the pipeline capacity between the two states. Williams Cos.’ Louisiana Energy Gateway Project, scheduled to come online in 2025, will add some additional capacity. The project was delayed six months in a legal battle with Energy Transfer.

McLean said that many other projects face similar difficulties, especially with cross-border transport pipelines that fall under federal oversight.

Meanwhile, the Northeast U.S. is a “graveyard for pipeline projects,” thanks to stiff opposition to any development in the region, he said.

The most likely outcome, therefore, is that the Haynesville Shale, located in northwest Louisiana and northeast Texas, will become the main supplier of a growing LNG market in South Louisiana. McLean said he expected an increase of 10 Bcf/d of demand from the basin through 2030.

Nevertheless, the available supply of cheaply produced gas from the region is not enough to meet the projected demand after the end of the decade.

“The Haynesville has the capacity to grow, but the longevity of the basin is in question,” he said. Producers will most likely need a higher return to keep gas production economically feasible in the Haynesville or will be forced to bring in product from further away.

Recommended Reading

Utica Oil E&P Infinity Natural Resources Latest to File for IPO

2024-10-05 - Utica Shale E&P Infinity Natural Resources has not yet set a price or disclosed the number of shares it intends to offer.

Post Oak Backs Third E&P: Tiburon Captures Liquids-rich Utica Deal

2024-10-15 - Since September, Post Oak Energy Capital has backed new portfolio companies in the Permian Basin and Haynesville Shale and made an equity commitment to Utica Shale E&P Tiburon Oil & Gas Partners.

Sheffield: E&Ps’ Capital Starvation Not All Bad, But M&A Needs Work

2024-10-04 - Bryan Sheffield, managing partner of Formentera Partners and founder of Parsley Energy, discussed E&P capital, M&A barriers and how longer laterals could spur a “growth mode” at Hart Energy’s Energy Capital Conference.

Oil, Gas Completions Company Covenant Testing Rebrands as One X

2024-09-25 - Covenant Testing said the name change to One X is meant to bring awareness to the company’s “comprehensive, end-to-end solutions for our clients.”

Steve Gray to Retire from Range Resources’ Board

2024-08-26 - Steve Gray, a member of Range Resources Corp.’s board of directors since 2018, will depart on Oct. 1.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.