Some of Jim Grice’s clients have been so focused on scooping up natural gas for data centers that they’ve invented a new, not-exactly-accurate conversion.

“I had a client call the other day and talk about how they had confirmed that they had 400 megawatts of gas supply at the site,” said Grice, co-chair of the energy and infrastructure team at Akerman, a corporate law firm based in Houston with clients around the country.

“I thought that was an interesting way to look at it. Usually, they talk about BTUs, and the person I was talking to was making the conversion from gas capacity all the way down to energy,” he told Oil and Gas Investor (OGI).

Grice’s office specializes in advising those in the business of data centers, real estate, electric power, energy and infrastructure. Its practitioners have a bird’s-eye view of the diverse business sectors developing artificial intelligence (AI) data centers and the buildup of energy supplies required.

It’s also a vantage point that offers some clarity on the complications involved. The energy industry is in the middle of building up massive nationwide energy infrastructure for data centers and these new facilities bring along new types of contract requirements. Among them, keeping prices stable for a commodity that fluctuates wildly.

Data centers are developing quickly and each facility’s lifespan comes with a question mark. For natural gas suppliers, that entails long-term commitments for a commodity with a price that is rarely stable.

Grice said the data centers and their gas suppliers will most likely find a solution, but challenges lie ahead.

Rising demand

Midstream companies pulled out positive forecasts aplenty during their second-quarter earnings calls, even as the Henry Hub price has struggled to remain above $2/MMBtu since June.

“There has been extensive discussion on this topic with the consensus developing that electricity demand will increase dramatically by the end of the decade, driven in large part by AI and new data centers,” said Rich Kinder, executive chairman of Kinder Morgan, during his company’s earnings call in July. “I’m a firm believer in anecdotal evidence, particularly when it comes from the actual users of that power and the utilities who will supply it, and from the regulators who have to make sure that the need gets satisfied. And the anecdotal evidence over the last few months has been jaw-dropping.”

The sentiment resonated throughout midstream earnings season.

“I guess everybody’s kind of seeing the truth,” said Energy Transfer Co-CEO Mackie McCrea during his company’s call. “We’re about to transfer into untold demand for natural gas.”

Williams Cos. CEO Alan Armstrong told investors that the number of inquiries his company has received from people looking for data center power has been “a little bit overwhelming.”

The available numbers back up the forecasts. AI queries are estimated to require 10 times the energy of traditional Google queries, according to a white paper published by the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), an energy market research organization based in Washington, D.C. By 2030, data centers could be consuming 9.1% of U.S. electricity generation, as opposed to 4% in 2024.

Grice said that AI requires a denser energy cohort than the typical data stack, Grice said. Cloud server racks typically work in the 8-kilowatt (KW) range. The AI technology clients he works with now are designing stacks to handle power loads in the 30- to 40-KW range.

Goldman Sachs forecasts the extra natural gas needed to support the energy load will be around 3.3 Bcf/d. The current overall U.S. gas demand is around 103 Bcf/d, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Through 2030, data centers and AI operations are expected to consume between 10% and 20% more electricity each year. Natural gas is currently the favored option based on its reliability and low emissions profile, Evercore ISI analysts said.

While the macro numbers are favorable, the tech and gas sectors are still working out how things connect locally, and how to factor in two major diverging trends happening at the national level.

Renewable preference

Many technology companies face a dilemma with their expansion proposals.

“First and foremost, I think all of the information technology industry would like to do as much sustainable and renewable energy as they can,” Grice said.

And renewable energy sources continue expanding. The EIA reported this spring that the amount of electricity generated from wind surpassed that from coal generation, setting a record.

However, renewables come with problems of their own. Wind and solar farms are often located in isolated places. Their output can fluctuate wildly when the wind drops or clouds cover the sun, which makes them a difficult choice for data centers that are running full-time.

“Most of those folks (tech companies) have very responsible approaches towards renewables and carbon emissions and climate change, but they still have a job to do as well,” Grice said. “That’s the balancing act for all of them.”

To tech companies, the solution is that other sources of energy, whether natural gas, nuclear or some of the developing sectors of electrical generation, such as hydrogen, will serve to “bridge the gap” left over by renewables, he said. Natural gas is the current go-to solution because it’s widely available and cheap, as opposed to building a small nuclear reactor on site.

However, the rapid deployment of data centers can cause a problem with an electrical supply system that is used to moving much more slowly.

Different times

Data centers can vary widely in scale and design, but the development cycle usually takes two years or less, depending on the availability of contractors and supplies. The permitting process and construction time for a gas-fired utility plant can range from one year to 10 years. Data centers also have the option to add on-site power generation.

Beyond that, a tech company will rarely commit to more than 20 years of occupancy on a lease. The largest AI facilities typically sign for 15 years, Grice said. Such a short time scale may run up against the investment required to build a power plant and ship the natural gas required to run it.

A gas generation plant usually does not amortize in 15 years and is generally more of a 30-year asset at a minimum.

“There will probably be some challenges of matching the operating pro forma of a gas power plant to the data center,” he said.

Beyond the decades-long considerations of a power plant, tech companies will also have the more immediate problem of dealing with the daily market fluctuations of a commodity. In just the last two years, the Henry Hub price for natural gas hit over $9/MMBtu in summer 2022, and sunk to under $2/MMBtu by spring 2024.

“There’s going to have to be some sophisticated purchasing of gas,” Grice said. “The disruptive cost of it is not a friend of data center operations.”

Still, Grice said price fluctuations were not a new problem in the industry and that a solution could be found, wherever the facilities are installed.

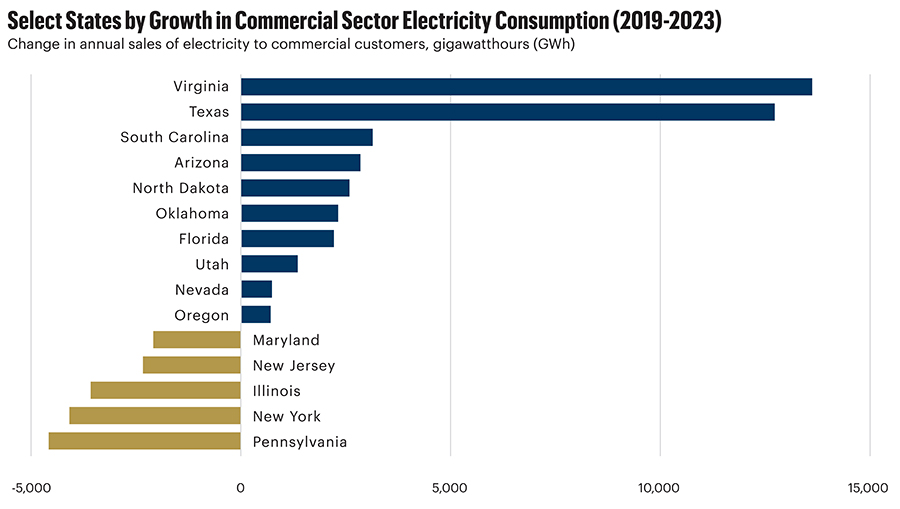

Virginia is king

In a growing nationwide data center market, Virginia is king. The state accounted for 22% of the nation’s data center demand, and the facilities consumed 23% of the state’s electrical load in 2023, according to the EPRI study.

Why Virginia? The state offers strong internet connections, few disruptive events, a labor force with the necessary skills and reliable backup power sources. The next three states offer some of the same amenities. Together with Virginia, the states of Texas, California and Illinois make up 50% of the current data center load, with most of the data centers located close to urban areas.

However, with the oncoming buildout of AI data centers, the location becomes less important, or at least more flexible.

The key difference is the importance of latency. For the applications that handle market transactions on Wall Street, a couple of microseconds can make a major difference when buying and selling. The data centers are, therefore, built close to the users.

AI applications generally perform best when the task isn’t time-sensitive, such as facial recognition, mapping applications or chatbots. With less of an emphasis on time, data centers have far fewer limitations on their location, according to TechHQ, a tech news website.

This allows tech companies to diversify their locations, focusing on available land and potentially nearby gas pipelines.

“You’re seeing projects popping up in the Dakotas, West Texas, areas of the country that really would not have been good candidates for traditional data centers,” Grice said.

In July, Houston-based tech company Lancium and Denver-based Crusoe Energy Systems announced that they were developing a 200-megawatt AI data center near Abilene, Texas.

Abilene is a town of 125,000 people two hours west of Fort Worth, Texas, along I-20, and home to three universities.

The region also has access to both types of power that tech companies are seeking. The nearby Trent Mesa project is one the state’s oldest and largest wind-power developments, and some of the state’s major gas lines crisscross the area.

At buildout, Lancium expects to have a 1.2-gigawatt project that will be one of the largest AI data centers on the planet.

Analytical firm RBN Energy recently published a study that projected a fizzle could happen with the power demands for AI.

Focusing on the Northeast, the firm found that growing supplies of renewable energy in the region could dampen the explosion in gas-generated demand before it happens. Renewable energy growth continues to trend upward nationwide.

The EIA recently forecast gas-fired generation in the region declining overall, from 5.2 Bcf/d in 2023 to 4.1 Bcf/d in 2030 in its latest forecast.

“AI may be the next big thing, but that does not necessarily translate to huge opportunities to supply natural gas to fuel the implied power demand,” RBN’s Rusty Braziel wrote in the analysis. “The data center industry’s focus on energy efficiency and technological advancements is likely to mitigate the anticipated increase in power consumption.”

Tech companies and energy suppliers will continue to move forward, however, with plans to supply a rapidly developing market. Data centers, regardless of how many are built, need a stable supply of energy. From Grice’s vantage point, tech companies are open to natural gas because of the reliability it provides to the grid.

“Natural gas can make a lot of sense in the right circumstances, the right location,” he said.

Irrationally exuberant forecasts?

Not all forecasts for an oncoming explosion in natural gas demand have been rosy.

Politico’s E&E news reported some consumer groups are concerned about paying for a power buildout that may not be needed if the demand ultimately fails to materialize.

In 1999, Forbes magazine published an article entitled “Dig more coal—the PCs are coming.” The piece predicted massive growth, about 13%, in electrical demand that would power the increasing use of the internet.

A follow-up study by the Berkeley National Laboratory found the Forbes story overshot its estimates, “in some cases by more than an order of magnitude.”

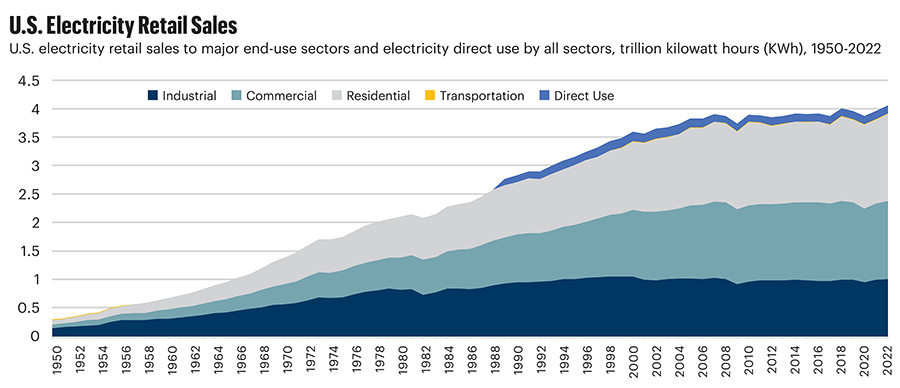

According to the EIA, the growth in retail electricity after 1999 continued at roughly the same pace as it had for the prior 30 years. In 2007, the growth rate flattened until the 2020s, when more demand from electrification began to come online.

While internet use did explode, new efficiencies in design and the retirement of older systems dampened the demand for a power buildout.

Recommended Reading

Sources: Citadel Buys Haynesville E&P Paloma Natural Gas for $1.2B

2025-03-13 - Hedge fund giant Citadel’s acquisition includes approximately 60 undeveloped Haynesville locations, sources told Hart Energy.

Will TG Natural Resources Be the Next Haynesville M&A Buyer?

2025-03-23 - TG Natural Resources, majority owned by Tokyo Gas, is looking to add Haynesville locations as inventory grows scarce, CEO Craig Jarchow said.

M&A Target Double Eagle Ups Midland Oil Output 114% YOY

2025-01-27 - Double Eagle IV ramped up oil and gas production to more than 120,000 boe/d in November 2024, Texas data shows. The E&P is one of the most attractive private equity-backed M&A targets left in the Permian Basin.

Report: Will Civitas Sell D-J Basin, Buy Permian’s Double Eagle?

2025-01-15 - Civitas Resources could potentially sell its legacy Colorado position and buy more assets in the Permian Basin— possibly Double Eagle’s much-coveted position, according to analysts and media reports.

Amplify Updates $142MM Juniper Deal, Divests in East Texas Haynesville

2025-03-06 - Amplify Energy Corp. is moving forward on a deal to buy Juniper Capital portfolio companies North Peak Oil & Gas Holdings LLC and Century Oil and Gas Holdings LLC in the Denver-Julesburg and Powder River basins for $275.7 million, including debt.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.