Catherine Little and Annie Cook are partners in the Washington, D.C., office of Bracewell law firm, where they advise oil and gas pipeline, associated storage and LNG clients across the U.S. on traditional and renewable energy, transportation and safety-related legal matters at federal, state and local levels.

CO2 pipelines are expected to play a key role in reducing greenhouse-gas emissions and achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 in the U.S.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects, many of which involved transportation by pipeline, are intended to capture and remove CO2 from the atmosphere and transport it to permanent underground storage or conversion sites. Certain of these projects are eligible for grants from the Department of Energy (DOE), which is tasked with providing “future growth grants” to fund CO2 projects such as CCS.

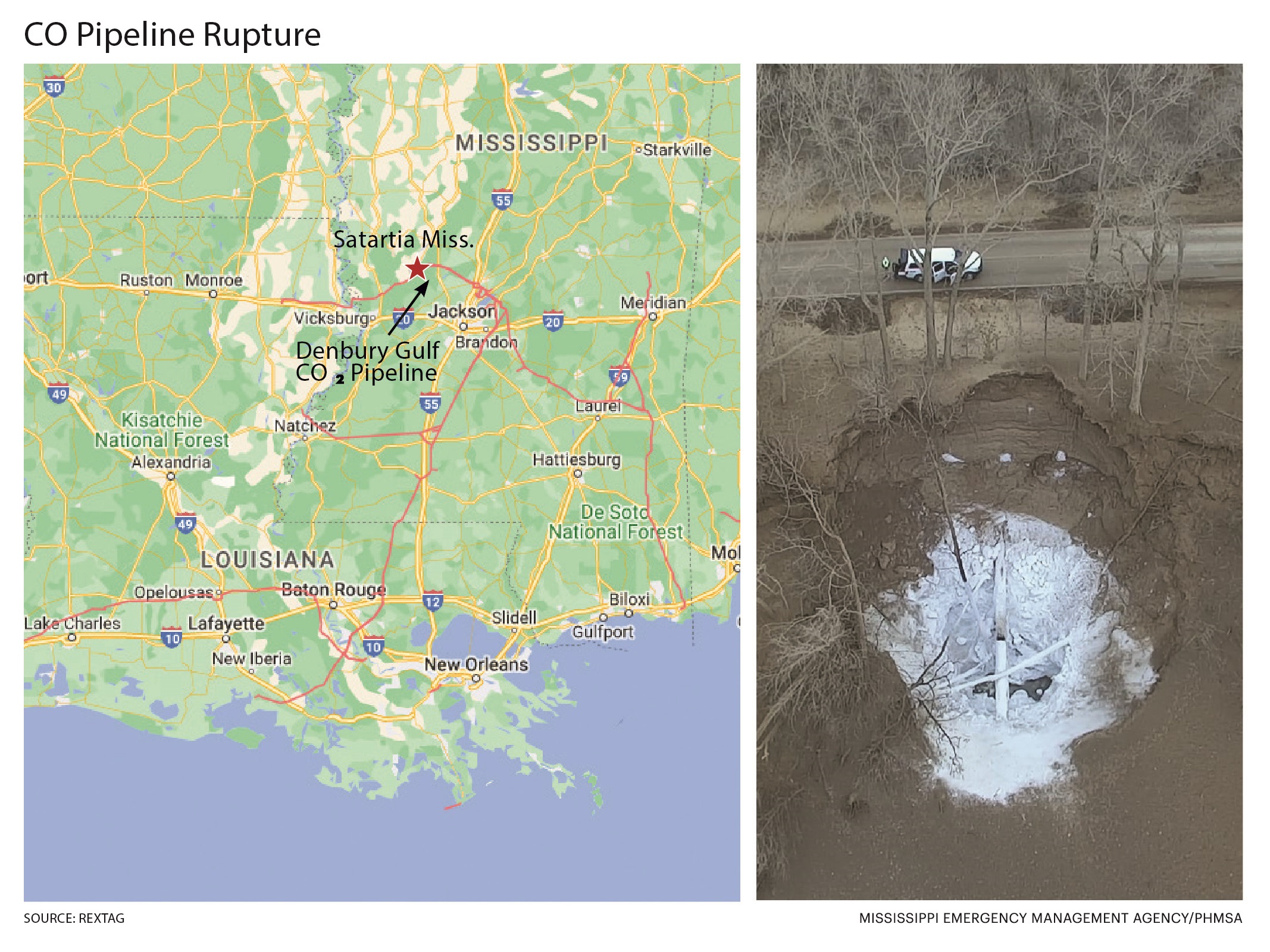

A critical path for success of CO2 projects depends, in part, on regulation by the Department of Transportation’s (DOT) Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, referred to as PHMSA. While pipelines are considered the most efficient and safest mode to transport CO2, the sufficiency of existing CO2 pipeline safety regulations has come under scrutiny in light of a 2020 CO2 pipeline incident in Satartia, Mississippi.

As CCS projects progress, third parties have called for updated CO2 regulations. Meanwhile, states and local governments have considered—and some have passed—moratoriums on CO2 pipeline projects until updated regulations are in place or local regulations are enacted to address what they see as gaps in the federal regulatory scheme.

It is a common misconception, however, that PHMSA does not regulate any CO2 pipelines, or that those regulations are not comprehensive. PHMSA has long exercised statutory and regulatory authority over the design, construction and operation of thousands of miles of CO2 pipelines. Further, PHMSA announced a rulemaking in 2022 to both update CO2 regulations and establish regulations for gaseous CO2 pipelines.

The agency has been slow, however, to rebut public misconceptions about regulation of CO2 pipelines and to issue a proposed rule. Such delays potentially hinder CCS projects and the ability of the U.S. to meet its climate goals.

Existing PHMSA regulations

Congress authorizes PHMSA to regulate the transportation of gas and liquids by pipeline, including both gaseous and liquid CO2, to protect against risks to life and property. Approximately 5,200 miles of regulated pipelines currently transport liquid (supercritical) CO2 in the U.S., which have been regulated since 1991. Current regulations for supercritical CO2 pipelines govern design, construction, operation, maintenance and emergency response planning, and many establish supplemental or different design, construction, operations and maintenance obligations specific to the unique risk profile presented by CO2, which is colorless, odorless, heavier than air and non-flammable.

PHMSA regularly monitors compliance of CO2 pipeline operators through routine inspections of pipeline facilities and construction projects, as well as accident response and investigations. Through enforcement, PHMSA requires remedial actions and assesses civil penalties, including a record proposed civil penalty associated with the Satartia incident.

As it relates to gaseous CO2, PHMSA has asserted that it maintains “safety authority” with the ability to investigate and address “any” safety issue through safety orders, even though the agency has not yet established regulations for gaseous CO2. PHMSA’s authority to regulate pipelines does not, however, extend to pipeline siting, routing or permanent storage.

Pending CO2 pipeline rulemaking and state laws

PHMSA has been working on its “priority” CO2 rulemaking to regulate gaseous CO2 and revise existing supercritical CO2 regulations specific to emergency response, conversion of service, dispersion modeling and leak detection and reporting. Based on public comments, other topics which may be addressed by PHMSA could include, among others, standards for impurities and odorization.

The Office of Management and Budget is currently reviewing PHMSA’s proposed rule, a review initiated in February 2024. As of this writing, the proposed rule was likely to be published at the end of 2024 or early 2025, although the change in administrations may impact the timeline for the proposed rule and, ultimately, the content as well.

Multiple states have considered issuing moratoriums on CO2 pipeline projects, and California and Illinois passed laws establishing such moratoriums until PHMSA finalizes its rule. California allows the state to pass its own regulations and the Illinois moratorium expires after a certain time has passed.

In addition, Congress is reauthorizing the Pipeline Safety Act in 2025 and current proposals floated by the House and Senate have addressed CO2 pipeline regulation in varying degrees. Industry trade groups have tried to fill the gap left by PHMSA’s slow march to updated regulations, such as the development of the “Carbon Dioxide Emergency Response Tactical Guidance” by API and the Liquid Energy Petroleum Association, to provide best practices for preparedness and initial response to a release of CO2. Meanwhile, some local governments have responded by attempting to put ordinances in place to establish their own moratoriums or to limit development, such as in Iowa and Illinois.

Challenges for CO2 project proponents

In 2021-2022, several large CO2 pipelines were proposed in the Midwest as part of larger CCS projects, aiming to reduce CO2 emissions. Opposition to those projects and/or the development of CO2 pipelines more generally has worked at federal, state and local levels to leverage the Satartia incident and the fact that the PHMSA has not yet issued updated regulations for CO2 pipelines.

On the other hand, pipeline proponents are facing challenges and have been hampered by the lack of clarity regarding CO2 pipeline safety regulation and the failure of PHMSA to expeditiously update its regulations, despite climate goals and DOE funding to incentivize such projects.

Existing and proposed projects face challenges with respect to permitting, other necessary regulatory approvals and possibly funding unless or until PHMSA issues a final rule. The “one government” approach should support these projects to meet the nation’s climate goals as well as provide additional jobs and other economic benefits.

Recommended Reading

BP Makes Gulf of Mexico Oil Discovery Near Louisiana

2025-04-14 - The "Gulf of America business is central to bp’s strategy,” and the company wants to build production capacity to more than 400,000 boe/d by the end of the decade.

E&Ps Posting Big Dean Wells at Midland’s Martin-Howard Border

2025-04-13 - Diamondback Energy, SM Energy and Occidental Petroleum are adding Dean laterals to multi-well developments south of the Dean play’s hotspot in southern Dawson County, according to Texas Railroad Commission data.

On The Market This Week (April 7, 2025)

2025-04-11 - Here is a roundup of marketed oil and gas leaseholds in the Permian, Uinta, Haynesville and Niobrara from select E&Ps for the week of April 7, 2025.

US Oil Rig Count Falls by Most in a Week Since June 2023

2025-04-11 - The oil and gas rig count fell by seven to 583 in the week to April 11. Baker Hughes said this week's decline puts the total rig count down 34 rigs, or 6% below this time last year.

IOG, Elevation Resources to Jointly Develop Permian Wells

2025-04-10 - IOG Resources and Elevation Resources’ partnership will focus on drilling 10 horizontal Barnett wells in the Permian’s Andrews County, Texas.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.