Tech executives’ uproar when OpenAI rolled out ChatGPT on Nov. 30, 2022, was spun as concern that generative AI was dangerously immature to reliably share facts rather than fiction.

It was about money, though.

Google, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon and the others weren’t ready to spend what was needed to release their own gen AI to compete in the “adapt or die” and “win or become IBM” contest of 1s and 0s.

The cost? Top-shelf GPUs, miles of racks in massive data centers and access to 24/7 electrons—up to 50 times more electrons than relatively lower-tech data storage and computing centers.

Curious, Oil and Gas Investor (OGI) asked ChatGPT itself what the fuss was about. It cited the “financial readiness for AI infrastructure” as the No. 1 reason for the upset.

Gemini, which Google rolled out a few months after ChatGPT hit browser tabs, disagreed when queried but acknowledged “the cost of developing and running AI models can be significant.”

In addition to Google and its Gemini, Microsoft quickly launched Copilot and Meta came out with Meta AI.

Tech companies have had to step up or go the way of those that lost the tech race to them in the past 30 years, analysts and investment managers say.

“Winners and losers are going to be decided,” said Matt Stephani, president of BOK Financial’s Cavanal Hill Investment Management. “If Microsoft is saying, ‘Hey, we’re looking at this $100 billion data center and we need 5 gigawatts (GW) of power,’ these other guys have to be looking at the same thing.

“They have no choice…. If you lose your edge, you lose your business.”

Thus “the power demand is real,” Stephani said. “The necessity to win the AI future is the most critical decision Microsoft, Apple, Amazon and [others] face: Either they [win] or they’re going to become IBM, and they know that.”

The AI revolution has made a winner and a loser in the chip industry itself with Intel Corp. bumped out of the Dow Jones industrial average in November after a 25-year run.

It was replaced with Nvidia Corp., which went public in 1999 at the same time Intel joined the Dow, at the equivalent of 4 cents a share, factoring for stock splits since. Shares were $140 in early December.

‘Blindsided utilities’

The seismic wave OpenAI made formed a tsunami of data-center-power-for-generative-AI that is now shocking U.S. utilities and natural gas demand forecasts with 10 GW thunderbolt upon thunderbolt.

Maeghan Rouch, a Bain & Co. partner, reported in October, “The late 2022 breakthrough in generative AI and the ensuing data-center boom blindsided utilities just as demand was also rising because of repatriated manufacturing, industrial policy and vehicle electrification.”

Eric Peters, CEO and CIO of Coinbase Asset Management, wrote this spring that an entrepreneur told him, “Every day, I’m surprised by how fast power consumption is growing. Take any application, add AI and you need seven times to 50 times the compute power.

“AI is a black hole; it’ll suck money out of everything else and into its vortex. The arms race between [tech] industry giants is a 20 on a scale of 1 to 10.”

Credit-analysis firm S&P Global Ratings researchers Aneesh Prabhu and Sudeep K. Kesh described the AI transformation as the fourth industrial revolution, following mechanization, electrification and digitization.

Nvidia’s new Blackwell chip’s processing speed, which is faster than its Hopper H100s, needs 4 megawatts (MW) of power for 2,000 GPUs in 90 days of training the newest ultra-large AI models, Prabhu and Kesh reported.

Evercore ISI energy analyst James West wrote, “Those seeking more power have begun to take matters into their own hands through onsite or islanded power solutions.”

He added, “The lag in deployment of generating assets support our bullish stance on natural gas and the ‘Bring Your Own Power’ thematic.

“… While we remain confident that solar-plus-storage solutions for utility-scale operations will become viable and more economic in time, the reality is the [data-center] demand pull is here and needs a reliable and accessible fuel source.”

‘More, like way more’

“When you look at the numbers, it is staggering,” Jason Shaw, Georgia Public Service Commission chairman, told The Washington Post this past spring. ”It makes you scratch your head and wonder how we ended up in this situation.

“… This has created a challenge like we have never seen before.”

Data centers use “eye-popping amounts of power,” Bain’s Rouch reported. “Serving a 1 GW data center requires the capacity of about four natural gas plants or around half of a [two-reactor] large nuclear plant.”

She determined that, “all told, meeting global data-center demand could cost more than $2 trillion in new energy-generation resources.”

Chips working on AI jobs may use between 35 kilowatts (kW) and 300 kW per rack, according to Prabhu and Kesh. (A data-center rack contains IT equipment like an IT cabinet but isn’t enclosed.)

“Models like ChatGPT can consume 80 kW/rack or more, compared with 15 kW for classic cloud,” they reported in October.

International Data Corp. anticipates AI clusters may grow to up to 100 kW/rack by 2030, they added.

Rebekah Eggers, innovation director, energy and resources sector for IBM, recalled a gathering at the Edison Electric Institute while speaking at the Gastech conference in Houston in September.

“There was a conversation between one of the utility executives and Elon Musk and the executive was super proud that we were going to have 60% more capacity on the grid, while Elon sat back and kind of said, ‘You’re going to need more, like way more,’” Eggers said at Gastech.

Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett said in his 2024 letter to shareholders that his outlook for U.S. power supply was “ominous.”

“When the dust settles, America’s power needs and the consequent capital expenditure will be staggering.”

At Gastech, Palantir Technologies’ Matt Babin, head of energy and natural resources, added that there was a recent meeting at the White House among chip manufacturers. “The numbers that came out of that meeting are staggering.”

While U.S. power generation and transmission aren’t looking like they’re going to catch up to this rapid growth in demand, Babin said, “you see all of these tech companies moving to say, ‘We’re going to generate our own power if we can’t rely on baseload from the grid to do this work.’”

Natural gas is the only means to fill all of the demand, Babin added, which is 24/7 for data centers. “There’s a cliche now in tech, ‘Move fast and break things,’ that was made famous by Meta,” he noted.

“That’s fine and good to say, but you can’t say that when the thing you’re breaking is the grid.”

Plus 50 GW

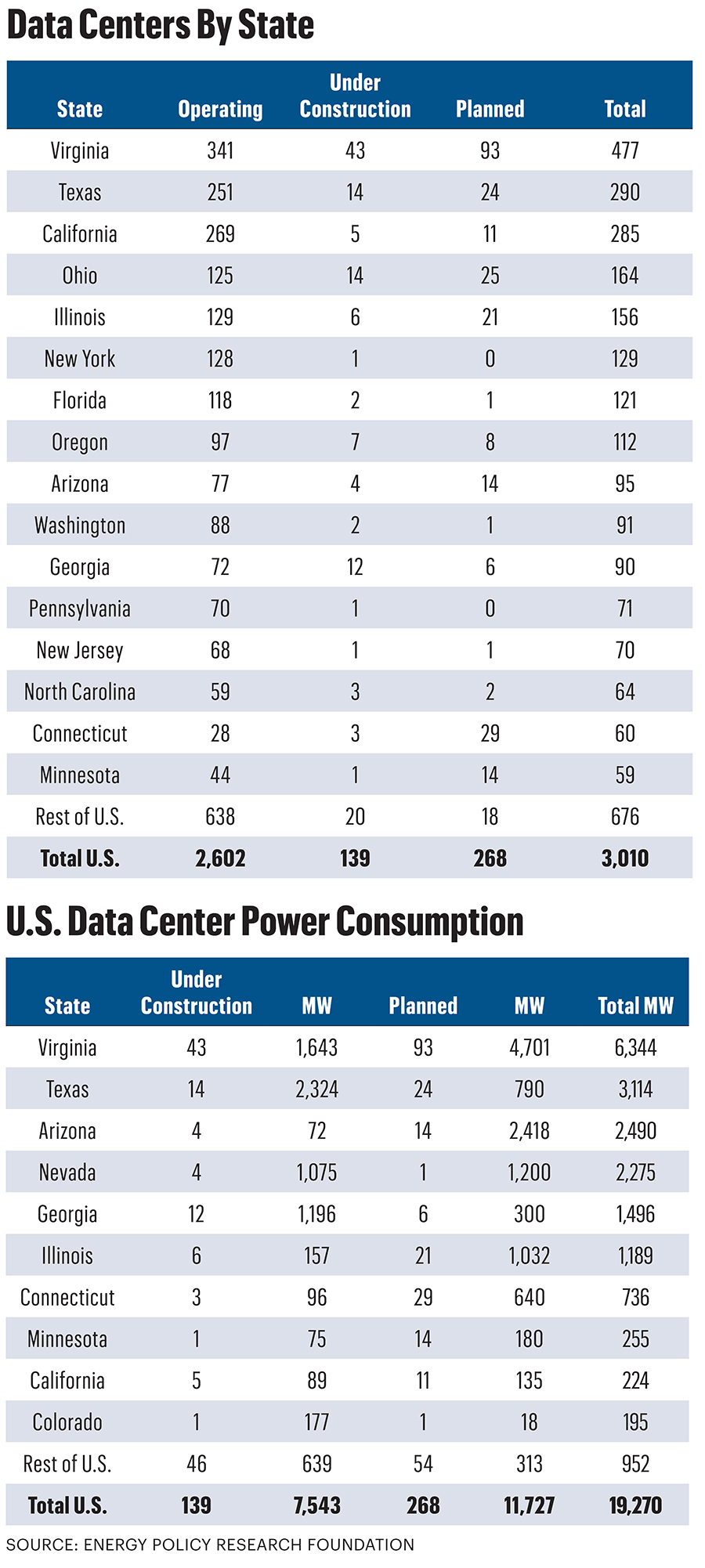

By early November, there were 2,602 data centers in the U.S. with another 139 under construction and 268 more planned, according to the Energy Policy Research Foundation (EPRINC).

It tallied additional 24/7 power needed for these as totaling 19.27 GW with 7.54 GW of this for those under construction and 11.73 GW for those that are planned.

For context, 19.27 GW would be the equivalent power from 23 nuclear plants the size of Three Mile Island’s Unit 1 reactor. Also, the largest U.S. nuclear plant is Southern Co.’s four-reactor Vogtle facility in Georgia, with capacity of 4.66 GW, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. The two newest reactors cost $37 billion and took 15 years to build.

E&P analyst Arun Jayaram with J.P. Morgan Securities came up with a similar number: 18.68 GW of additional demand in 2027 versus 2022 demand.

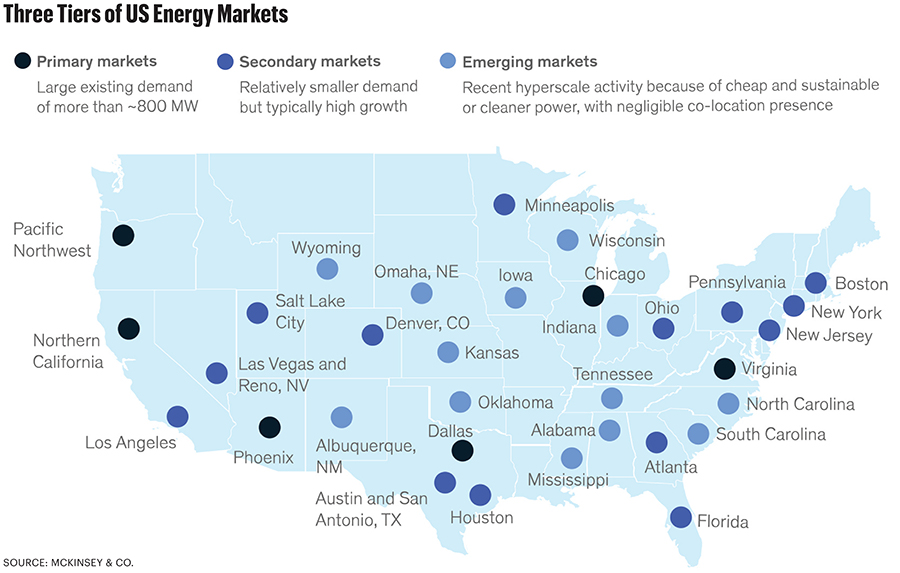

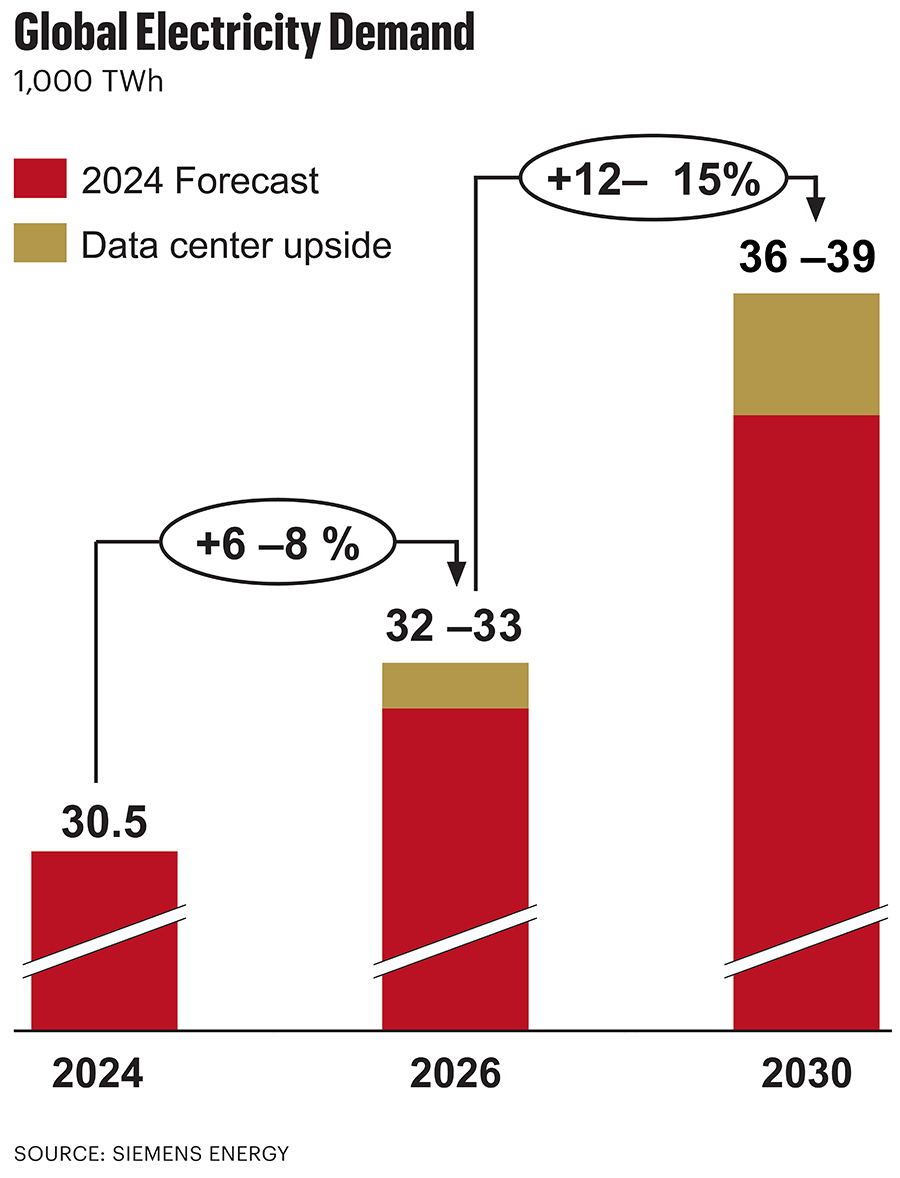

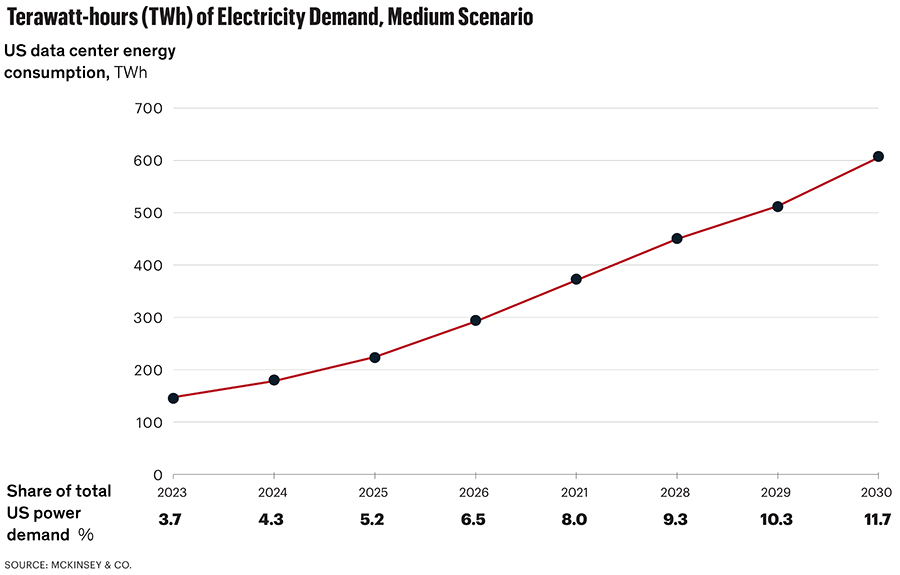

Meanwhile, McKinsey & Co. analysts are forecasting U.S. data-center power needs will grow from 25 GW to more than 80 GW in 2030.

S&P Global Ratings’ through-2030 figure is similar: 50 GW.

“That looming demand has taken the power sector by surprise … necessitating about $60 billion of investment in generation and $15 billion in transmission,” the S&P analysts, Prabhu and Kesh, reported.

Like electric utilities and regulators, they added that they and their colleagues were surprised, too.

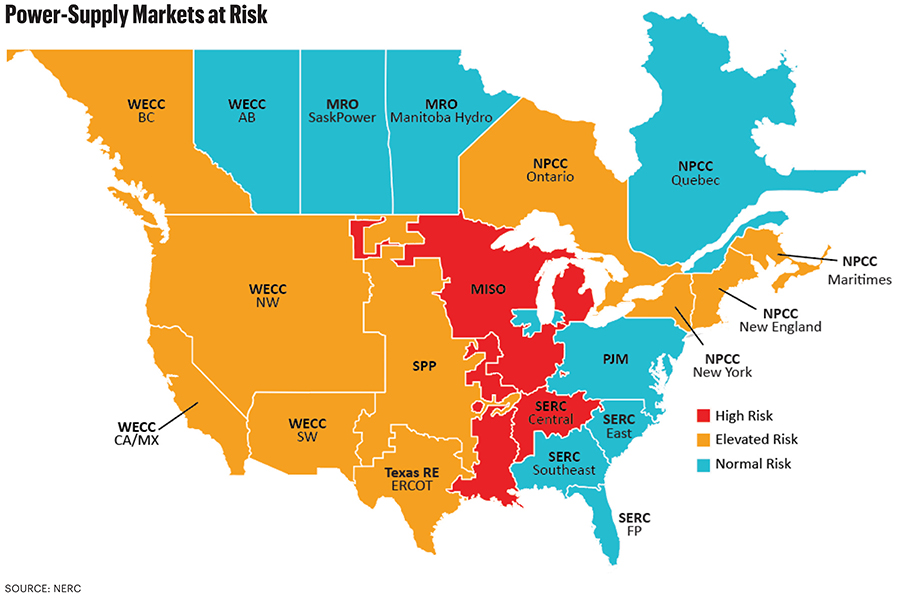

PJM—the independent system operator (ISO) in the Appalachian region, serving Pennsylvania and 12 other states, plus the District of Columbia—reported at the start of 2024 that the CAGR (compounded annual growth rate) of demand in its area through 2030 would be 1.7%—more than double the 0.8% it forecast in January 2023.

“The news did not grab our attention because we are used to industry revising forecasts and tweaking them later,” Prabhu and Kesh wrote. “But then, forecast revisions started accelerating.”

By June 2024, their colleagues in S&P’s commodities group revised their CAGR expectations for U.S. Lower 48 power demand to 2.1% through 2030 rather than the 1.2% expected six months earlier.

Overall, the new S&P forecast is that net Lower 48 power demand growth into 2030 will be 542 terrawatt-hours (TWh) to total 4,699 TWh. This includes power for data centers but also for EVs, general U.S. economic growth and conversions to electric heating, while deducting for behind-the-meter solar (personal power plants that feed excess electrons onto the grid) and energy efficiency.

“For perspective, the annual consumption of New York and California is 150 TWh and 250 TWh, respectively,” Prabhu and Kesh wrote.

Gas turbines talk

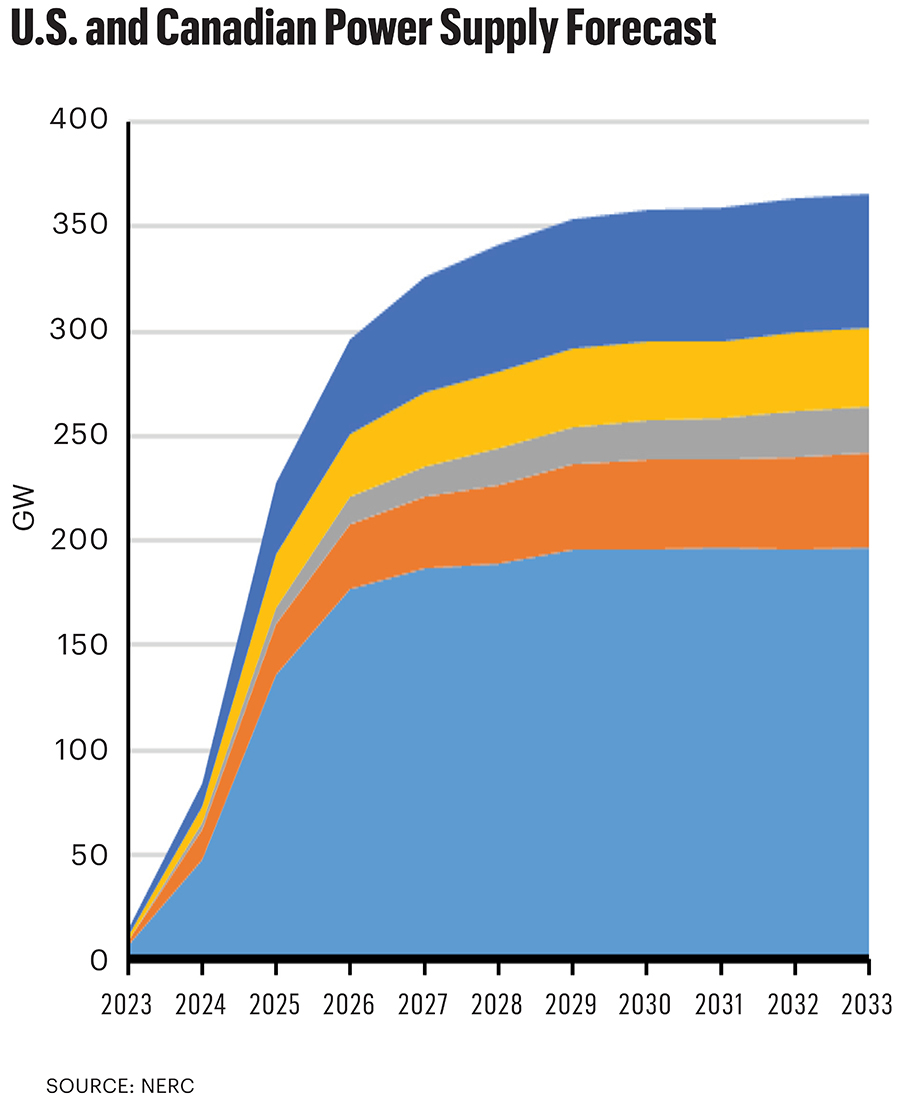

Orders globally for natural gas turbines grew 33% in the first nine months of 2024 to 42.8 GW of generation capacity compared with 32.1 GW of orders in the first nine months of 2023, according to McCoy Power Reports.

The 2024 orders are for 279 turbines. When excluding orders from China, which declined in 2024, the demand was up 61% to 36.7 GW year over year, J.P. Morgan’s Jayaram reported in December.

“North America saw an 88% year/year increase over the first nine months of 2024, with the U.S. contributing 92% growth—9.2 GW vs. 4.8 GW—driven by increased electricity demand,” Jayaram reported.

Maria Ferraro, CFO for Siemens Energy, said in a November investor call, “We have an order backlog of EU$123 billion of which I can say is a record.”

Siemens forecasts global power demand will grow by up to 8,500 TWh to total 39,000 TWh by 2030 with 1,600 TWh of this coming from data centers.

McKinsey counted 21 utility companies mentioning data centers in their earnings calls this past spring compared with only three in 2021.

“The demand for data centers and power shows no sign of slowing,” McKinsey reported. “… Advances in gen AI will create even more data, increasing the need for data storage centers to avoid issues that come with managing large quantities of data.”

Stephen Tusa Jr., an industrials analyst for J.P. Morgan Securities, wrote in August that “commentary by utility companies around their data-center pipelines [were] all indicating that this is not showing any signs of slowdown and comfortably extends until the end of this decade.”

Permian gas

Texas’ Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT)—one of three power grids in the Lower 48—forecasts that customers’ peak power demand could reach 152 GW in 2030. This is 62 GW more than the 2024 peak, Tusa noted, and nearly twice what ERCOT had estimated in 2023 for 2030 demand.

Texas produced 1 Tcf of natural gas in August, according to Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC) data. Half of this was from Texas’ side of the Permian Basin, which is frequently overwhelmed by associated gas supply from its oil wells, resulting in a negative market price in the area.

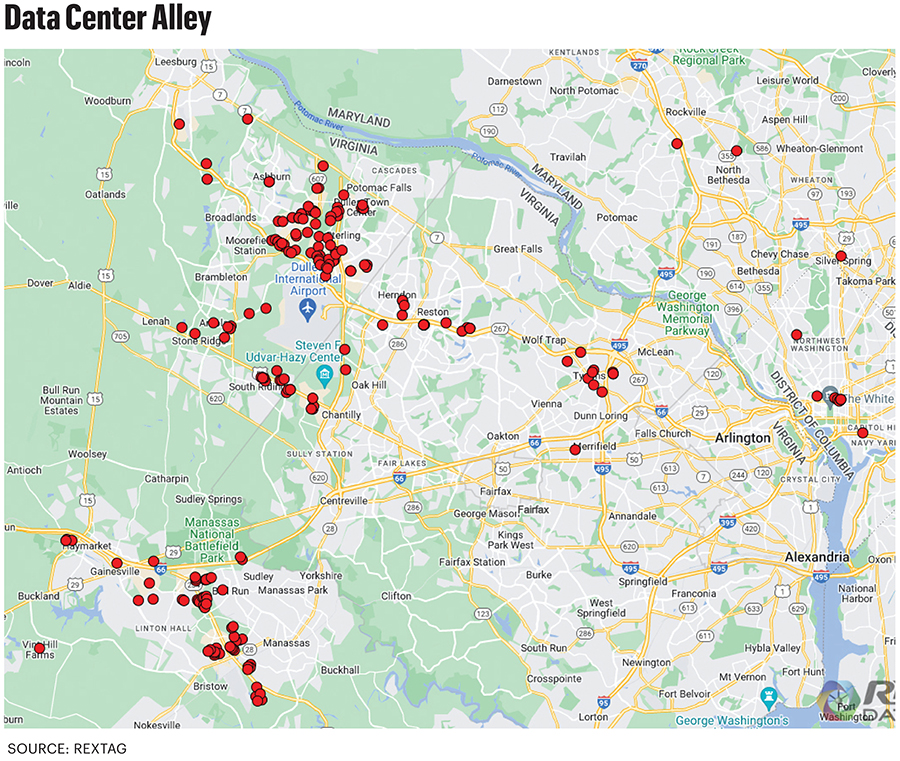

Of the U.S.’ existing data centers, 251 are in Texas—thirdmost after Virginia’s 341 and California’s 269—according to EPRINC.

For the 14 additional data centers under construction in Texas and 24 more planned, the state will need an additional 3.114 GW of power, EPRINC calculated.

In the Permian, conversations with data-center builders have started, but developers largely “have not been focused on the Permian yet,” Kaes Van’t Hof, CFO of Diamondback Energy, said in a November investor call.

Diamondback is the Permian’s largest independent producer, including a total of 2 Bcf/d of associated gas following its September merger with Endeavor Energy Resources. All of that is from the Texas side of the Permian Basin, according to RRC data.

“We’re kind of putting the flag out there that this [gas] is a very cheap way to execute their business model,” Van’t Hof said.

Separately, Riley Exploration Permian, which produced 1 Bcf in August, is in a 50:50 joint venture with Conduit Power, building 10 MW of gas-fired power generation to sell onto the ERCOT grid beginning this year.

Danny Smedley, a managing director for Priority Power, has customers looking for where to site their data centers to get access to the grid, including in West Texas.

“It’s a crazy busy time for us,” Smedley said. Among the firm’s services is sourcing power solutions for clients from offices in Texas, New York and Chicago.

The priority in choosing a data-center location—in “Data Center Alley” in northern Virginia or elsewhere—is access to power, Smedley said.

“I haven’t heard of anybody saying, ‘Hey, I don’t want to be in Virginia’ or ‘I don’t want to be here,’” Smedley said. “They’re more about ‘Get me to market’ and ‘Where can I get power the fastest?’”

The hyperscalers are less concerned about price. “They just want to get power as fast as they can,” Smedley said.

‘No solution’ other than gas

Tom Jorden, chairman, CEO and president of Permian, Appalachian and Midcontinent producer Coterra Energy, was asked in a November investor Q&A for his view on the call on U.S. natural gas for power demand.

“We study this as well as anybody can,” Jorden said, “and we try to look at viewpoints that don’t have economic or ideological investment in the outcome.”

No matter the projections, the power will have to come from natural gas, he said.

“There’s no other solution in the timeframe in which this power will be required and the reliability that will be required for this power,” Jorden said. “There’s no solution available other than natural gas for the bulk of it.

“So, even if you’re at the low end of the projection, it’ll be very, very constructive for natural gas demand.”

Shane Young III, Coterra’s CFO, added, “When it comes and exactly how big it is—[from] the materials that we look at and the conversations that we have—there’s a bit of a wide berth of where that could ultimately end up.”

But somewhere between 30% and more than 40% of the power growth could come from gas, Young said.

“And it’s going to have to be something like [gas] that’s got that kind of reliability and dispatchability…. We can’t wait to see it materialize and manifest itself into gas prices.”

Appalachian gas

The largest concentration of U.S. data centers is in northern Virginia—Data Center Alley—with 341 of the 2,602 in the Lower 48.

Of the 19.27 GW of additional U.S. data centers under construction or planned, 6.34 GW are sited in Virginia with 43 under construction and 93 planned, according to EPRINC.

Between 2009 and 2019, Virginia’s commercial power demand growth averaged 1.4% per year. This grew to 5.8% per year between 2019 and 2023, EPRINC reported.

“At this rate, [Virginia’s] commercial power demand will double within 12 years,” it reported.

Bill Appicelli, head of North American power and utilities research for UBS Securities, reported after Appalachian utility PPL Corp.’s earnings call in November that “requested load in-service increased in Pennsylvania to 8 GW from 5 GW and in Kentucky to 400 MW from 350 MW.

“… Active data-center requests now total 31 GW in Pennsylvania, up from 17 GW previously.”

Vincent McCullough, a vice president with construction firm Hines, said at Hart Energy’s DUG Appalachia conference in Pittsburgh, “We have clients that have requested anywhere from 25 [MW] to 30 MW of power for a data center.

“And in the last two months, that number’s increased to 50 MW.”

McCullough added, “The gas market has an opportunity to pick up where the utility grid is kind of dropping the ball right now because their infrastructure is so aged.”

Ravi Srivastava, president of new technologies for Appalachian gas producer CNX Resources, said expectations are natural gas will fuel at least 50% of power demand growth.

Power provider Vistra Corp., which operates from California to Maine, sees a 40 GW supply deficiency by 2030 in each of its two largest markets, for example: PJM and ERCOT.

The 40 GW deficit in each factors for plant retirements and is derived from PJM and ERCOT’s own forecasts, Stacey Dore, Vistra chief strategy and sustainability officer, said in a Federal Reserve program in November.

“We’re going to have a supply gap because retirements are happening more quickly than we’re bringing on new supply,” Dore said.

This is no matter what the data-center demand-growth figures turn out to be, she added.

‘Pretty important tailwind’

The largest U.S. natural gas producer, Expand Energy, is in conversations to directly supply some of its nearly 7 Bcfe/d of net gas output to data centers, executives confirmed in an October investor call.

Expand produces from the Appalachian Basin, which has reached is pipe-takeaway capacity, and from the Haynesville Shale in northwestern Louisiana, which has virtually unlimited takeaway to the Gulf Coast industrial and LNG demand centers.

The producer was formed in October by the merger of Chesapeake Energy and Southwestern Energy in a $7.4 billion deal. Of its combined production, about 63% is from the Appalachian Basin.

“Those conversations have been happening in the background,” Expand CFO Mohit Singh said.

“We are in the process of consolidating the efforts that legacy Southwestern was doing on its end and what legacy Chesapeake was doing on our end,” Singh said.

Participants in the discussions include data-center developers, power-generation companies, end-users, midstream operators and gas producers.

“It’s fair to say there is lots of interest from all the different stakeholders involved in that value chain,” Singh said.

Expand President and CEO Nick Dell’Osso said, “Demand domestically is clearly growing—and growing faster than I think a lot of models were predicting … one to two years ago.”

A lot of the power demand for AI “is going to take several more years to develop,” he added. But the call on U.S. gas will be “structural and long-term and provide a pretty important tailwind.”

Up to 118 Bcf/d

Fellow Appalachian producer EQT Corp. told investors that data-center buildout and other U.S. power-demand growth is expected to result in an additional 10 Bcf/d of U.S. gas demand by 2030—and possibly as much as 18 Bcf/d.

U.S. gas demand is currently some 100 Bcf/d.

At Range Resources, also an Appalachian gas producer, executives confirmed that positioning for Marcellus gas-fired power generation is heatedly underway in the region.

It added a slide on this to its investor presentation in October “to try and put some color around that,” said Dennis Degner, Range president and CEO. “There are a lot of conversations that are starting to materialize around data centers’ future power demand.”

A PJM auction in July “probably shed some light on the critical movement … around power in the future,” he said.

In the capacity auction, bids reached $270 per MW/d from $29 a year before, according to PJM. In the Baltimore area, capacity went for $466 per MW/d.

In utility Dominion Energy’s area—including Data Center Alley—capacity sold for $444 per MW/d.

“So, there’s some early indication that movement [on securing power supply] has taken shape,” Degner said.

Five governors in the PJM area pushed back. They estimate the auction results will cost homes and businesses $14.7 billion, they wrote to PJM.

Bain’s Rouch reported, “In the U.S. alone, adequately funding the capital investments to serve data-center growth over the next decade would require utilities to generate 10% to 19% in additional revenue each year than previously forecast.”

PJM reported after the July auction that it “remains concerned with the slow pace of new generation construction.”

Some 38 GW have been approved “but have not been built due to external challenges, including financing, supply chain and siting/permitting issues,” it reported.

Hines’ McCullough said at the DUG Appalachia conference, “I could take you to probably five, maybe six, facilities that are in northern Virginia right now that are only operating on 40[%] to 50% of the power that they requested.

“And that’s because those grid utility providers can’t get them the power.”

Rockies gas

Utah Gov. Spencer Cox announced “Operation Gigawatt” in October. “We need to double the power production in the state of Utah over the next 10 years,” he said.

He had just returned from meeting with tech leaders and government officials in South Korea and Japan.

“Everywhere I went, the same conversation happened: It was a conversation around energy,” Cox said.

In Utah, 24/7 power supply was already facing a deficit while a prior administration had been “pushing to phase out baseload power before we had baseload dispatchable power to take its place,” Cox said.

But the situation is more urgent now as “something else happened that I wasn’t prepared for … and nobody else was prepared for,” which is power demand for generative AI.

One data-center developer in Utah is requesting 1.4 GW of power. Utah itself currently operates on 4 GW. All of Wyoming operates on 900 MW. So the 1.4 GW data-center campus planned for Utah needs 1.6 times the power of all of Wyoming, he noted.

Most of Utah’s natural gas reserves are in the eastern Uinta Basin, which is adjacent to Colorado’s gassy Piceance Basin across the Utah-Colorado border.

Two of energy investor Quantum Capital Group’s portfolio companies bought Caerus Oil and Gas’ Uinta and Piceance assets for $1.8 billion in August.

QB Energy is picking up the Piceance property; Koda Resources, the eastern Uinta property. Chuck Davidson, a Quantum partner, said in the announcement, “Natural gas lays an increasingly important role in our energy grid …

“The Caerus assets provide access to some of the largest natural gas resources in the western markets, which have experienced repeated, localized energy shortages in recent years.”

‘Start drilling again’

Williams Cos.’ Candyce Fly Lee, general manager who runs the pipeline company’s Salt Lake City-based operations, told OGI, “We’re starting to see a lot of regional demand with the push for electrification and data centers.

“We’re getting a lot of regional crypto-mining, coal-togas switching and data centers,” Lee said.

South of Salt Lake City on the western edge of the Uinta Basin, Novva Data Centers built its own on-site 200 MW substation that uses some 50 MMcf/d of natural gas for its1.4 MMsq ft facility.

In Wyoming, Meta announced in July that it is putting an $800 million data center in Cheyenne across a highway from one of three Microsoft already has in the area.

Williams, which moves one-third of U.S. natural gas, added MountainWest to its portfolio in 2023 for $1.5 billion of cash and debt assumption, picking up some 2,000 miles of transmission pipe across Utah, Wyoming and Colorado, as well as 56 Bcf of gas storage.

The area includes the Uinta, Piceance, Denver-Julesburg and Greater Green River basins.

“Most of your major transmission pipelines in the West touch our pipeline,” Lee said. “I consider us the gas hub of the Rockies.”

The gassy eastern Uinta and the Piceance, “they’re going to have to step it back up and start drilling again a bit more,” Lee said.

International gas

Naser Al Yafei, a senior vice president with gas exporter ADNOC Gas, said at Gastech, “As a reliable, efficient and lower-carbon-intensity source of energy, natural gas is the most viable and flexible solution for the increasing power demands for data-center servers, cooling and backup generation.”

Arun Kumar Singh, chairman and CEO of India-based international operator ONGC, said the numbers he’s seeing are that data centers currently consume some 460 TWh and it is likely to grow to 1,000 TWh by 2026.

Renewables alone won’t work, he added. “I’m 100% sure for a country like us, the cheapest power is solar,” ONGC’s Singh said.

“The only problem of solar is that at night, it doesn’t work.… There is no substitute to gas for some years.”

Bain’s Rouch noted in October that power suppliers worldwide “face the same pressing issue,” notably in Canada, Ireland, Germany, the United Arab Emirates and India.

Ireland recently forbade more data-center development in Dublin through 2028. Data centers consume some 20% of the country’s electricity.

Rouch wrote, “Data centers’ annual global energy consumption could more than double by 2027 from 2023 levels, growing at a compound annual rate of 10% to 24% and potentially surpassing 1 million GWh in 2027.”

Nuclear options

In stunning news, Microsoft and Constellation Energy Group struck a deal in September to restart the Three Mile Island nuclear plant’s Unit 1 reactor in Pennsylvania to power new data centers.

But the 835-net-MW reactor’s restart is “not a needlemover” against natural gas demand growth from the AI boom, EQT president and CEO Toby Rice told OGI.

“There’s only 3 GW of nuclear potential if we restart all facilities that could be restarted.”

Meanwhile, new power demand to fuel—and cool—data centers as well as other demand growth could be as much as 75 GW, he said.

The Three Mile Island plant, which became uneconomic in the wake of new Appalachian natural gas supply beginning in the late aughts, was shuttered in 2019. (It was the plant’s Unit 2 reactor that experienced a partial meltdown in 1979 and was shuttered at that time.)

The target date for Unit 1’s restart is 2028. The deal comes at a price, noted Julien Dumoulin-Smith, power and utilities analyst for Jefferies: $110/MWh, which is “higher even than investors’ expectations for a behind-the-meter contract,” he reported.

David Arcaro, an analyst with Morgan Stanley, calculated the price as $100/MWh. That is “a substantial premium to market power prices of about $50/MWh.”

In addition, Microsoft’s deal has it “still receiving power directly from the grid, paying an approximately $30/MWh transmission charge on top of this payment to Constellation,” he added.

“From our perspective, we think this shows that Microsoft was willing to pay a $130/MWh all-in power price for nuclear power.”

Meanwhile, Amazon and Google have announced deals for SMRs—small modular nuclear reactors—Google with Kairos Power; Amazon with Energy Northwest, Dominion and X-Energy.

SMRs aren’t the near-term power solution, though, Priority Power’s Smedley said, mostly due to regulatory and permitting constraints. “It would be years and it’s still not proven.”

But they could be helpful when they come onto the market, he added. “I hope the technology proves out. We need every possible source to produce power.”

SMR developer Oklo Inc. reported in November that it had orders for another 750 MW from two datacenter developers, bringing its total pipeline to 2,100 MW. Separately, it has nonbinding letters of intent from Diamondback Energy as well as Centrus Energy, Prometheus Hyperscale and others.

Its SMRs, which remain in R&D, are expected to produce between 15 MW and 50 MW, delivered directly to the customer’s facilities. First deployment is expected in 2027.

Behind-the-meter options

Data-center developers would prefer to have their own power plant or plug directly into someone else’s, skipping the grid. This is known as a “behind the meter” solution and typically involves “co-location” with the power source.

“You almost essentially have a microgrid onsite that you self-distribute to the data center itself,” Colleen Turley, senior manager for mobile power operator AMP, said at the DUG Appalachia conference.

“And by having a partner on the gas end, you can almost insulate your risk.”

A behind-the-meter nuclear deal met in November with Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) rejection, though.

In it, Amazon was to buy Houston-based Talen Energy’s 960 MW data center, Cumulus Data Assets, that is plugged into Talen’s 2,700 MW Susquehanna nuclear plant in eastern Pennsylvania, for $650 million.

Power producers Exelon Corp. and American Electric Power filed a complaint.

Two FERC commissioners said they didn’t see a need for the deal. Another commissioner said rejecting it created “unnecessary roadblocks to an industry that is necessary for our national security.” Two other commissioners did not vote.

The deal was rejected 2-1.

Talen has appealed.

Recommended Reading

Baker Hughes Appoints Ahmed Moghal to CFO

2025-02-24 - Ahmed Moghal is taking over as CFO of Baker Hughes following Nancy Buese’s departure from the position.

Chevron Technology Ventures Would Like to See the Manager

2025-03-13 - Chevron Corp.’s Chevron Technology Ventures, which turns 25 this year, pays close attention to leadership teams when making investment decisions in technology startups.

Shell Shakes Up Leadership with Upstream and Gas Director to Exit

2025-03-04 - Zoë Yujnovich, Shell’s Integrated Gas and Upstream director, will step down effective March 31.

NextEra Energy Resources CEO Rebecca Kujawa to Retire

2025-03-18 - NextEra Energy CFO Brian Bolster will become CEO for NextEra Energy Resources, and NextEra Energy Treasurer Mike Dunne will become CFO, the company says.

BKV Appoints Dilanka Seimon to New Chief Commercial Officer Position

2025-04-03 - BKV Corp. has created a new chief commercial officer position and placed industry veteran Dilanka Seimon in the role.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.