Tight storage, cold weather in Texas and tensions between Ukraine and Russia are shaking up oil markets, but actions by OPEC+ remain a huge influence. (Source: Cctm, Nice to meet you, LukeOnTheRoad, Prapat Aowsakorn/Shutterstock.com)

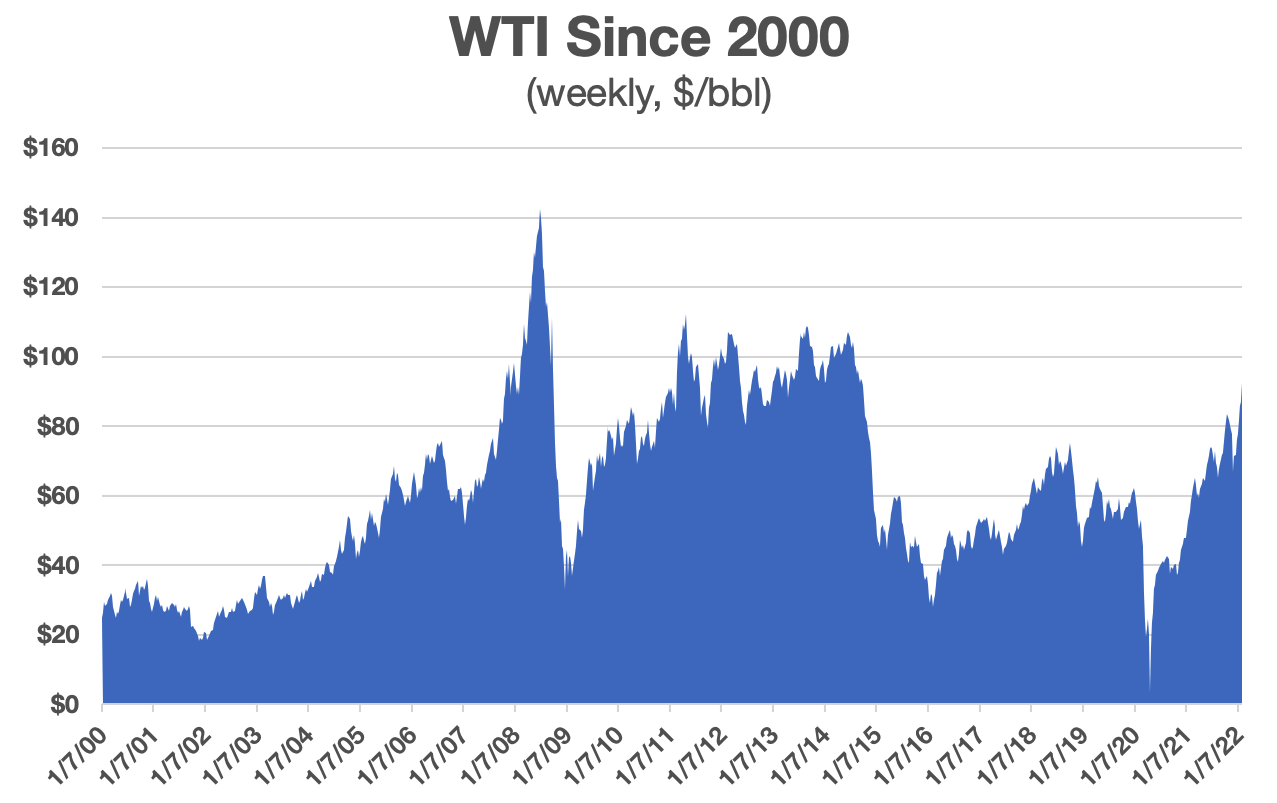

Tensions between Ukraine and Russia, and Permian Basin oil production hampered by cold weather, are prompting nervous traders to push WTI closer to $100/bbl, but those factors only come into play around the edges, a leading energy authority told Hart Energy. The biggest driver is a tight market.

“Over the last year, inventories have fallen sharply and even in the first couple of weeks of this year, the deficit continues to widen,” said Mark Finley, fellow in energy and global oil at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. “So, to me, it’s not at all surprising that prices have been rising. While geopolitical risk concerns and weather concerns enter into it, the big story behind it is tight fundamentals, driven by recovering demand and policy choices of the so-called OPEC+ group.”

WTI closed at $92.65/bbl on Feb. 4.

Finley said he could envision prices rising higher if inventories continue to fall sharply and OPEC+ members continue to resist entreaties from the Biden administration to accelerate production. The cartel has been raising output incrementally every month after aggressively cutting output when the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020. That process should be complete during the second half of this year.

RELATED:

Strategists See Oil Hitting $100 on Strong Demand, Russia-Ukraine Crisis

And while the oil markets are roiled at the moment, most analysts believe the tight supply will begin to ease by spring and into the second half of the year, Finley said. He noted that production from both U.S. and OPEC+ is rising, as are inventories. The prices locked in for delivery later in the year are lower than they are now.

That said, the markets could just as easily wobble the wrong way.

“Will the economy stay strong?” he asked. “Will U.S. producers become more aggressive in how they invest or will they try to be disciplined? Will the OPEC+ group continue to increase production and do they have the ability to do so? Some people think that most of their members don’t and they don’t have that capacity anymore.”

That’s where geopolitical concerns such as the Ukraine situation factor in. Conflict between Ukraine and Russia would further complicate matters, he said. Russia is the world’s largest exporter of oil and gas and second largest net exporter of oil (including refined products) after Saudi Arabia. A lot depends on both the physical flow of oil and gas, and policy action by Russia and the U.S.

“The simple fact is, there is not enough spare capacity and inventory to deal with a full disruption of Russian supplies of either oil or gas,” Finley said. “A full disruption of Russian oil and gas would be, in effect, the biggest supply disruption ever.”

The Houthi attack on Saudi Arabia’s Abquiq and Khurais oil processing facilities in 2019 involved a bigger supply disruption, but it was only for a few days. In durable terms, he said, a full disruption of Russian oil and gas would be bigger than the loss of oil after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

“A lot of the kind of safety buffers of the oil market are kind of stretched right now,” Finley said. “There’s not much spare production capacity outside of the Middle East. Inventories are very low. In times like that, when the fundamentals are tight, people get really worried about the political risks.”

Recommended Reading

Targa Pipeline Helps Spark US NGL Production High in 2024

2025-01-23 - Analysts said Targa Resources’ Daytona line released a Permian Basin bottleneck as NGLs continued to grow.

Phillips 66 Makes EPIC Move to Strengthen South Texas Position

2025-01-09 - Phillips 66’s $2.2 billion deal with EPIC allows for further integration of its South Texas NGL network.

Kissler: Wildcards That Could Impact Oil, Gas Prices in 2025

2024-11-26 - Geopolitics and weather top the list of trends that will determine the direction of oil and gas.

EIA: NatGas Storage Withdrawal Eclipses 300 Bcf

2025-01-30 - The U.S. Energy Information Administration’s storage report failed to lift natural gas prices, which have spent the week on a downturn.

LNG, Crude Markets and Tariffs Muddy Analysts’ 2025 Outlooks

2024-12-12 - Energy demand is forecast to grow as data centers gobble up more electricity and LNG liquefaction capacity comes online in North America, but gasoline demand may peak by 2025, analysts say.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.