Ring Energy Chairman and CEO Paul McKinney, put it aptly: “The best place to find oil, oftentimes, is where you’ve already found it.”

Oil is easy to find, but assets are expensive to buy in the core of the Permian Basin, which is locked up. The breakneck pace of consolidation in the past two years places the highest-quality acreage in the hands of the majors and a few massive E&Ps. Tier 1 Permian locations are expensive to buy through M&A and even more difficult to discover organically.

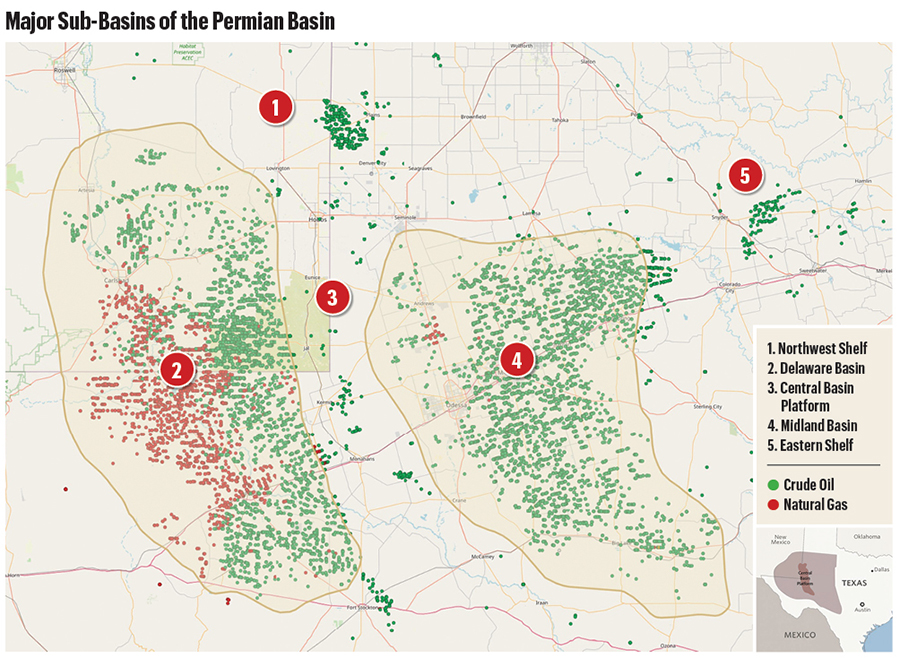

But the far edges of the Permian—the Central Basin Platform (CBP), the Northwest Shelf and the Eastern Shelf—remain accessible for the independent producers pushing the play’s boundaries and testing relatively unpopular zones.

Not the Spraberry, but the Strawn and San Andres. Not the Bone Spring, but the Blinebry. Think Paddock, Canyon, Clear Fork, Grayburg and Barnett Shale.

In these less popular benches, independent and family-owned producers are making wells with Permian Basin economics but outside the Permian’s core.

These plays might never pique the interest of the majors, or even the large- and mid-sized public producers. But for the small public and private producers with the geological know-how and the risk appetite, bountiful oil and natural gas resource is the prize.

Of course, oil isn’t hard to find in these conventional and semi-conventional reservoirs. Some of the earliest and most legendary discoveries in West Texas and New Mexico were made there.

And, as the Permian’s shale rock gets drilled and matures over time, experts think producers will take harder looks at what’s left on the CBP and the basin shelves in the future.

RELATED

'A Renewed Look': Central Basin Platform's Old Rock Gains New Interest

Old rock, new techniques

The Permian Basin is expected to drive U.S. oil production for the foreseeable future, but a century ago, the energy potential of West Texas and eastern New Mexico was only starting to

be understood.

West Texas first made it to wildcatters’ maps when the famed Santa Rita #1 came online in Reagan County in May 1923, marking the discovery of the Big Lake oil field.

Drilled to a depth of 3,050 ft into the “Big Lime” formation (later designated the San Andres), Santa Rita #1 produced for 67 years before being plugged in 1990.

The 1926 discovery of the Yates Oil Field in nearby Pecos County is credited as the first major oil discovery on what’s known today as the Permian’s Central Basin Platform.

The Great Depression and the discovery of the massive East Texas Oil Field in 1930 delayed exploration of sparsely populated West Texas for some time. But other major discoveries along the CBP and Northwest Shelf include the Wasson (1937), Goldsmith (1935), Slaughter (1937) and Seminole (1936) fields.

The Wasson Field, in Yoakum and Gaines counties, Texas, was still the eighth-largest U.S. field by proved reserves in 2015, the last time the Energy Information Administration ranked oil field reserves. Ahead of Wasson were giants like Prudhoe Bay, Alaska and Colorado’s Wattenberg Field.

So, when Riley Exploration Permian leadership thought about drilling horizontal San Andres wells on Yoakum County acreage a stone’s throw away from the Wasson Field, the company was pretty sure it would strike oil.

“We are offsetting one of the largest, legacy oil fields in America, which has produced over 2 billion barrels,” Philip Riley, executive vice president and CFO at Riley Permian, told Oil and Gas Investor (OGI). “We believe that’s a good depositional setting.”

Riley Permian started out with assets in Yoakum County, but has since expanded its footprint west on the Northwest Shelf. The company paid $330 million to acquire a largely undeveloped position in Eddy County, New Mexico, in early 2023.

Today, Riley Permian is one of the largest publicly traded companies operating on the Northwest Shelf, where unconventional drilling techniques are being applied to conventional rock.

“Sometimes we bifurcate things into black and white: Is it unconventional? Is it conventional?” Riley said. “The reality is, it’s probably not quite so bifurcated and it’s more of a spectrum.”

Riley Permian’s asset is categorized as conventional. But the company is developing that conventional rock with horizontal drilling and fracking processes largely associated with unconventional development.

“It’s the combination of those two that’s allowing this to work,” he said.

Indeed, the marriage of unconventional drilling techniques and conventional oil-bearing zones is giving runway to independent producers all around the edges of the Midland and Delaware basins.

Gideon Powell, CEO of Cholla Petroleum, an Eastern Shelf E&P, calls them “hybrid” reservoirs.

“I truly believe the independents and the small, family-owned companies are going to play the biggest role going forward on unlocking new reserves,” Powell said. “Exploration of these hybrid reservoirs, I think, is in its infancy.”

RELATED

Power Players: Riley Permian Natgas, Conduit Electrifying Permian

In the middle

The CBP and Northwest Shelf are garnering renewed interest by producers searching for future drilling locations, McKinney said.

Ring has grown in the CBP and Northwest Shelf through a string of acquisitions since McKinney joined the company as CEO in October 2020.

Until that point, the CBP and Northwest Shelf were “basically dominated by private companies,” he said during Hart Energy’s A&D Strategies and Opportunities Conference in October.

The area is still mostly dominated by private operators. Outside of Ring, the CBP’s top producers include Blackbeard Operating, Elevation Resources, Formentera Partners, Maverick Permian and Lime Rock Resources, according to an analysis of Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) and Enverus data.

Occidental Petroleum, APA Corp., Exxon Mobil and Kinder Morgan Production Co. also produce large volumes from legacy assets on the CBP.

Lime Rock Resources’ CBP asset in Andrews County, Texas, came with a mix of existing vertical and horizontal wells. Its 2017 acquisition of the Shafter Lake oil-weighted assets from seller Forge Energy signaled the company’s entrance into the horizontal San Andres play.

Lime Rock has been focused on horizontal development on the platform since then, said Jonathan Hickman, COO at Lime Rock.

“We’ve largely moved away from legacy assets unless they have a significant amount of future horizontal development that makes sense for us,” Hickman said.

Over the past year, most of Lime Rock’s Permian oil production has come from the San Andres Formation, according to RRC data. The company has also drilled seven wells targeting the Devonian bench since entering the play, Hickman said.

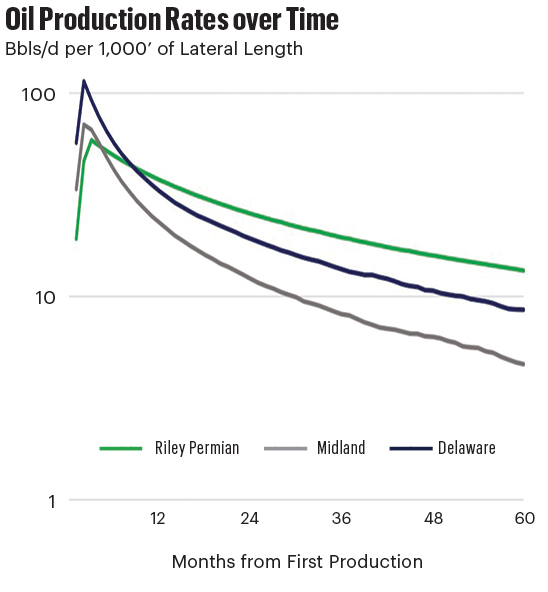

Operators like Ring and Lime Rock enjoy the horizontal San Andres play because of its relatively low drilling costs and shallow production declines.

Ring can drill a San Andres well with a 1- to 1.5-mile lateral for between $2.3 million and $3.7 million, with costs ranging between $435 to $467 per lateral ft.

Diamondback Energy spends about $600/ft in the Midland Basin, even after combining with Endeavor Energy Resources, the company reported in third-quarter results. Permian Resources spends around $800/ft in the deeper Delaware Basin.

Ring is also drilling to vertical depths of around 5,000 ft, compared to the deeper Wolfcamp, Spraberry and Bone Spring shale formations that attract most of the Permian’s investment.

Ring’s San Andres wells don’t have the same initial production spike than do a Spraberry or Wolfcamp well. Ring reports initial peak oil rates of 300 to 700 bbl/d. Wells in the core of the Permian can see IP rates of over 1,000 bbl/d.

But Ring finds that San Andres horizontal wells have lower production declines and higher primary recovery than shale wells.

Producers are also searching in parts of the CBP for Barnett Shale upside. Elevation Resources has been drilling the Emma Barnett field on the CBP since 2016.

Lime Rock has drilled a single Barnett well, Hickman said. Larger operators like Occidental Petroleum and Continental Resources have also drilled in the Emma Barnett field recently.

“Typically, to the east side of the Central Basin Platform, we see more activity related to the Barnett,” said Leslie Armentrout, president and co-founder of CBP producer Silver Cross Energy Partners, “and that has increased the value of stuff right on the edge of the platform.”

RELATED

Barnett & Beyond: Marathon, Oxy, Peers Testing Deeper Permian Zones

Shelf life

The San Andres play extends from the CBP into the nearby Northwest Shelf, which spans from the northern reaches of the New Mexico Delaware Basin into West Texas.

Ring and Riley Permian’s San Andres assets in and around Yoakum County, Texas, are on the Northwest Shelf.

Riley Permian’s 2023 acquisition gave the company a foothold in a different part of the Northwest Shelf: New Mexico’s Yeso Formation. The company mainly targets the Yeso’s Paddock and Blinebry formations, said President and CEO Bobby Riley.

Spur Energy Partners, another top producer in the Yeso trend, typically targets the same formations, said co-CEOs Jay Graham and Kyle Roane. Spur launched in 2019 with backing from KKR and a large team from WildHorse Resources Development, where Graham was formerly CEO.

WildHorse sold its Eagle Ford asset to Chesapeake Energy for nearly $4 billion in 2018.

Instead of acquiring land, drilling quickly and flipping the assets to a buyer, Spur aimed to develop a more sustainable, cash flow-focused business—acquiring PDP assets and using cash flow to fund a drilling program.

With a team with years of experience drilling horizontal wells in the South Texas Eagle Ford, East Texas and Louisiana, Spur liked the Northwest Shelf asset’s existing base production and upside for future drilling.

“We like the ability to come into a conventional play and drill horizontal wells,” Roane said.

Spur grew on the shelf through a series of acquisitions, including a $925 million deal with Concho Resources in 2019.

Spur is one of the top producers on the Northwest Shelf today. Production averaged approximately 32,000 boe/d in August, according to data from the State of New Mexico. Spur aims to exit 2025 at around 40,000 boe/d, Roane said.

Spur and Riley like the Northwest Shelf for similar reasons that Ring and Lime Rock like the CBP’s San Andres conventional rock.

“Being a conventional play, our cycle times are much, much shorter than the shale plays—and it’s shallower,” Graham said. “We’re drilling wells in five to six days.”

On a dollar-per-foot basis, Spur’s Yeso wells are “quite a bit cheaper” than shale wells landed in the Midland and Delaware basins, he said.

Spur’s wells are coming in with IP rates at between 500 and 1,000 boe/d.

Plus, Graham said, the conventional play doesn’t “have the same initial decline rates year over year that you see in the shale plays.”

Riley Permian touted similar well results in its third-quarter earnings report.

And as Delaware Basin delineation and drilling activity moves north, producers think it’s only a matter of time until that activity reaches the Northwest Shelf.

There is no “magical demarcation” or line in the sand between where the Delaware Basin stops and the Northwest Shelf starts, Graham said.

“You could be standing on one location and a geologist would consider you in the Northwest Shelf,” he said, “and you can hit a golf ball to the Delaware Basin.”

But the difference matters to public investors. E&Ps focused on the core of the Permian are typically more favored in the public markets.

Investors also like scale, which public producers on the CBP and shelves lack. Riley Permian ($733 million) and Ring Energy ($304 million) barely clear $1 billion in market value between them.

“I believe small cap valuations are not going to be the same when compared to large cap companies,” Bobby Riley said. “We have observed that scale does impact valuation.”

Riley Permian has demonstrated “solid” financial performance, a commitment to return capital to shareholders in the form of dividend distributions for the past five years and the ability to grow production year-over-year, all while lowering capital spending.

“We are among the leaders in our peer group with those numbers and our performance holds up well, even when compared to large-scale companies,” Bobby Riley said. “Our objective is to match pace with larger companies as we continue to build scale.”

RELATED

Deep Dive in Shallow Ground: Jay Graham on the Northwest Shelf [Watch]

M&A interest

Dealmaking interest on the CBP and Northwest Shelf started heating up once again this summer, McKinney said.

In September, APA Corp., parent company of Apache, announced a $950 million sale of conventional assets on the CBP and Northwest Shelf to an undisclosed private buyer, reportedly Hilcorp Energy.

The divested assets had estimated net production averaging 21,000 boe/d (57% oil). The non-core asset sale came after APA closed a $4.5 billion acquisition of Callon Petroleum, deepening Apache’s portfolio in the core of the Midland and Delaware shale plays.

Exxon Mobil also is selling select conventional assets in the area to Hilcorp for roughly $1 billion. Exxon closed its own $60 billion acquisition of Midland Basin giant Pioneer Natural Resources earlier this year.

The Exxon and APA deals were for legacy, PDP-weighted assets with relatively limited future horizontal upside, executives said. But some E&Ps are searching for that kind of cash flow-boosting PDP through M&A.

“It was extremely competitive on the Apache deal,” Roane said. “We liked the level of interest that the Northwest Shelf got and the allocation of value that the Apache deal did have on the Northwest Shelf asset.”

Interest for these assets was high because of the huge amount of resource left to be recovered, lowering operating costs and marginally improving production, Hickman said.

But legacy, PDP-weighted assets are of less interest to an operator like Lime Rock Resources.

“For us, the [plugging and abandonment] liability, the environmental liability of all those old assets, just kind of outweigh the benefits that we see for right now,” Hickman said.

RELATED

APA Divests $950 Million in Non-core Permian Basin Assets

Chasing the strawn

Industry veterans didn’t believe Bob Eagle when he told them about the horizontal Strawn wells his company was drilling on the Permian’s Eastern Shelf.

“They’d say, ‘No you’re not,” Eagle told OGI. “You’re not in the Strawn, you’re in the Cline or the Wolfcamp Shale.’”

The Strawn Formation was already well-known to Eagle, president of Clear Fork Inc. of Abilene, Texas, and oilmen like him on the Eastern Shelf. Vertical oil production from the Strawn interval dates to 1920, according to state records.

“We’ve all drilled through it or for it our whole careers,” said Eagle, who has operated Clear Fork on the Eastern Shelf since 1981.

But it was the horizontal development of the Strawn sands starting in 2015 that kicked off a frenzy of new investment, leasing and drilling activity in the area.

“Part of that is a lot of the old-timers in Midland just didn’t believe these results could be happening on the Eastern Shelf,” Eagle said.

Nearly a decade later, Clear Fork ranks among the top oil producers on the shelf, after drilling or participating in about 60 horizontal wells.

Clear Fork and other top operators have learned much about the Strawn sands—and the challenging variability drilling the interval across the play—over that period.

With the public E&Ps so focused on the Midland and Delaware basins, the Eastern Shelf Strawn play has emerged as a sort of “independent paradise,” Eagle said.

“But I would say there’s a fine line between paradise and a graveyard,” he added. “Most people would say it’s a graveyard, but that’s what makes it interesting.”

Other top producers on the Eastern Shelf include Moriah Energy Investments, Verado Energy, and Cholla Petroleum.

Chris Graham, president and CEO of Verado Energy, remembers well the Eastern Shelf’s leasing frenzy last decade. He helped kick it off.

Historically active in the East Texas Oak Hill Field, Verado was looking for new runway when Graham was introduced to King Operating at an industry conference.

King Operating had acreage and vertical Strawn wells on the Eastern Shelf—but the company was looking to boost production, Graham recalled.

The two producers discussed Verado’s experience fracking legacy vertical wells at Oak Hill and pondered how similar techniques could be applied on the Eastern Shelf.

“We decided it’s not a good idea to frac the whole wellbore and try to get as many zones comingled at once,” Graham said. “But since you know the Strawn’s producing, it looks like it’s got some characteristics where we said, ‘Let’s go horizontal on this.’”

![PHOTO: Chris Graham Verado Energy.jpg[CM2]](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Chris%20Graham%20Verado%20Energy.jpg)

With King as operator and Verado as a non-operated interest holder, the companies completed the Dessie 91 #1H well in Scurry County—near the town of Hermleigh, Texas—in August 2015, Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) filings show.

“It came in phenomenally, especially for a half-length horizontal well,” Graham said. “After seeing the results on that, we said, ‘Let’s drill a full-length one.’”

Verado and King teamed up on a second well, the Kate 143 Unit #1H, which went to sales in 2016. Impressed by its performance, too, Verado bought out King’s interest and took operatorship of the Hermleigh assets.

“We finished up that third well and we just kept going from there,” Graham said.

Operators kicked off a land rush after seeing Dessie’s impressive output, and the Eastern Shelf’s horizontal Strawn play was born.

Since the Dessie well came online, operators have drilled nearly 200 new horizontal wells in Scurry and Fisher counties, according to RRC data.

And after nearly a decade of exploration, testing and drilling, producers are looking for new upside on the Eastern Shelf.

RELATED

On The Shelf: Strawn Wells an Independent Paradise or Graveyard?

Shelf moves south

Moriah has been active on the shelf since 2015, but started a new leasing effort the next year, spudding its first horizontal in 2018, Moriah President Tyler Harris said.

The company still has a few locations left to drill in the core Scurry-Fisher part of the shelf. Moriah completed a 10,500-ft lateral, the Hannah #1H, in Scurry County last year. Verado contributed some of its acreage to Moriah to make the 2-mile well fit, Graham said.

But Moriah has also been active to the south, in Tom Green and Irion counties, Texas, near San Angelo, RRC data show.

Moriah’s first horizontal in Irion County, Tullos Unit #1H (~8,000-ft lateral), was completed in November 2023 targeting the Canyon bench. RRC records show production from Tullos Unit #1H peaked at approximately 712 bbl/d in January.

A Strawn well completed in Tom Green County last December—Mozelle Unit #1H (~10,500-ft lateral)—produced over 600 bbl/d in April.

Harris was tight-lipped on the recent activity in the southern Eastern Shelf.

“That play is very early on its life cycle and we’re still evaluating results to assess the return profile and attractiveness of that area,” he said.

Moriah is delineating the play along with Rising Star Energy Partners, which has submitted data on five wells drilled in Irion County.

Clear Fork has ventured into that part of the Eastern Shelf yet, but Eagle acknowledges that “they’re making really, really nice wells there.”

“It’s two-tiered—it’s a Strawn and Canyon sand,” he said.

Repeatability and scale

Producers on the CBP or Eastern or Northwest shelves have fewer shots on goal and smaller sandboxes to play in, compared to the core Permian plays.

Permian producers and their public investors favor the Permian’s stacked pay of multiple productive benches: From the popular Wolfcamps, Spraberrys and Bone Springs to the more exploratory Avalons, Deans, Barnetts, Woodfords and Devonians.

On the Eastern Shelf, a producer might be able to land a lateral in a single zone, Eagle said. Two, if you’re lucky. In the Yeso trend in New Mexico, producers have the Paddock and Blinebry zones. It’s a similar situation on the CBP, where the San Andres has been a top producing interval.

There is stacked pay potential further to the south of the platform, where Ring is drilling vertical wells from the shallow Clear Fork to the deeper Wolfcamp zone in Ector and Crane counties, Texas.

But drilling a 21-well pad targeting six different benches, like Devon Energy did in the Delaware Basin, really isn’t an option for producers on the platform or shelves.

Differences in rock quality and well spacing also constrain these plays.

Wells can typically be drilled closer together in the tight shale rock plays. Producers on the CBP, Eastern Shelf and Northwest Shelf have generally gone with wider, conservative well spacing to reduce interference through the porous, permeable conventional rock.

“Overspacing is just as much acceleration in reserves as it is finding new reserves,” Bobby Riley said. “Our approach has been to avoid overspending dollars unless there is a high degree of certainly as to what we’re doing.”

That reduces the amount of white space on a map for an E&P to work with, so to speak. And it’s why they’re considered small plays.

Replicating success from well to well across these small plays has also been challenging in certain areas.

What the shale revolution brought was the concept of a resource play being repeatable, Riley said.

“Shale resource plays took out some of that risk and uncertainty,” he said. “Whereas, people historically associated ‘conventional’ rock with more uncertainty and less repeatability. You don’t know what you’re going to get from one well to the next.”

Producers on the Eastern Shelf report significant variances from well to well across the play.

“We can’t sell anything,” said Powell at Cholla. “No one’s going to give any value to the upside because we can’t even internally explain why it works sometimes.”

And it’s not just the shelves and the CBP. Even bigger plays like Wyoming’s Powder River Basin are notorious for variability in the deeper stacked pay zones.

But as U.S. shale matures, producers will increasingly consider the smaller plays, said Continental Resources Executive Chairman Harold Hamm in an interview with OGI.

The reality is the industry probably won’t find another Permian Basin or Bakken Shale that’s yet to be discovered, Hamm said.

“There are going to be smaller targets that people go look for,” Hamm said. “There’ll be some other ideas, but the magnitude is not going to be the same.”

RELATED

Harold Hamm: ‘Drill, Baby, Drill’ Faces Geology Barriers, Even Under Trump

Recommended Reading

Utica Oil Player Ascent Resources ‘Considering’ an IPO

2025-03-07 - The 12-year-old privately held E&P Ascent Resources produced 2.2 Bcfe/d in the fourth quarter, including 14% liquids from the liquids-rich eastern Ohio Utica.

Expand Appoints Dan Turco to EVP of Marketing, Commercial

2025-02-13 - Expand Energy Corp. has appointed industry veteran Dan Turco as executive vice president of marketing and commercial.

Japan’s JAPEX Backs Former TreadStone Execs’ New E&P Peoria

2025-03-26 - Japanese firm JAPEX U.S. Corp. made an equity investment in Peoria Resources, led by former executives from TreadStone Energy Partners.

Michael Hillebrand Appointed Chairman of IPAA

2025-01-28 - Oil and gas executive Michael Hillebrand has been appointed chairman of the Independent Petroleum Association of America’s board of directors for a two-year term.

Chevron to Lay Off 15% to 20% of Global Workforce

2025-02-12 - At the end of 2023, Chevron employed 40,212 people across its operations. A layoff of 20% of total employees would be about 8,000 people.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.