(Source: Shutterstock)

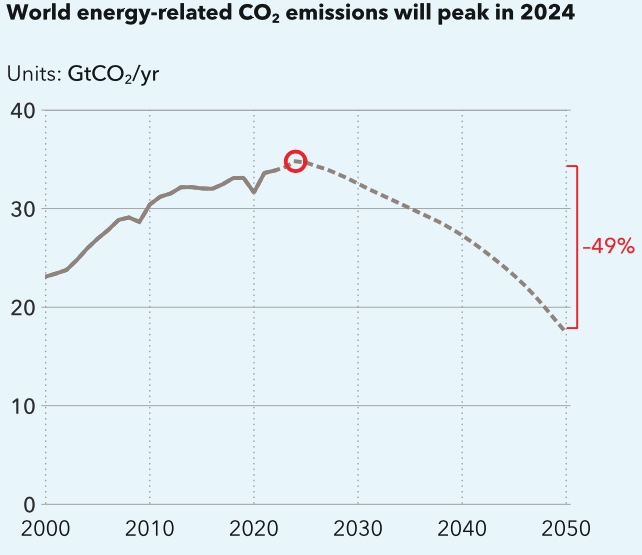

Energy-related emissions are expected to peak this year as solar, batteries and wind move toward global domination of electricity grids, Norwegian risk manager DNV said in its latest global energy transition outlook.

The 260-page outlook, released late Oct. 8, predicts a sharp spike in the adoption of electric vehicles in the next six years, oil use at 65% of its current energy share by 2050 and a far less robust hydrogen market than DNV previously forecast.

However, emissions still will not fall fast enough to meet the ambitious climate goals set by world governments.

“We expect around 2.2 degrees of global warming by end of this century, which is much better than the 3 or 4 C of warming you would get if doing nothing,” Sverre Alvik, vice president and director of the energy transition outlook at DNV, told journalists. “But it’s also very far from the one and a half degree Paris Agreement ambition that the world agreed to achieve. … The main reason we see global emissions peak in 2024 is that oil is replaced by electricity in transport, and coal is replaced by solar in the electricity.”

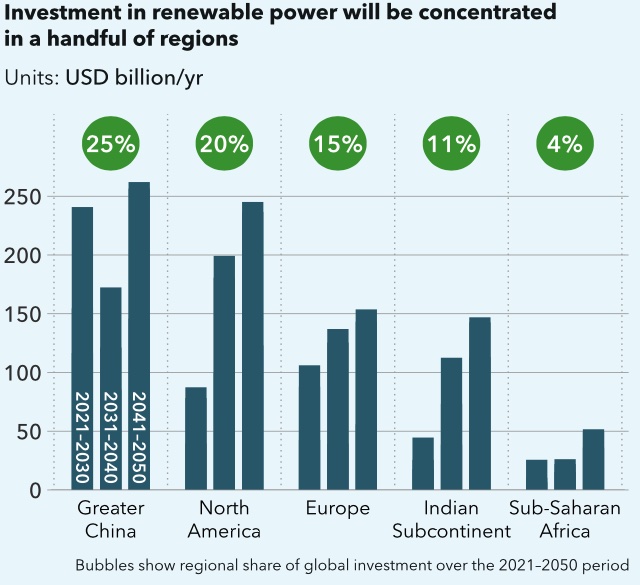

The outlook was delivered after DNV took a look at what is working and what needs improvement to help accelerate a transition to lower-carbon energy. Some technologies seen as playing key roles in lowering emissions are faring better, while others are growing slower than expected. Factors impacting the pace of the transition include China’s competitive clean energy technology clash with national and economic security priorities, particularly in North American and Europe, according to the DNV.

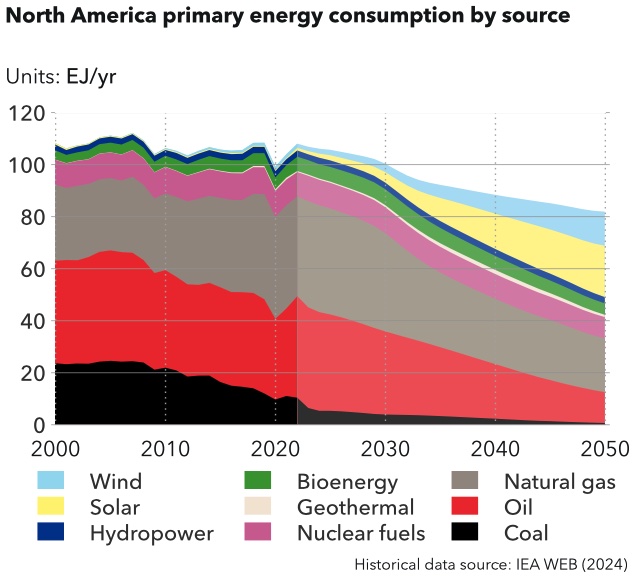

“Despite these challenges, the peaking of emissions is a sign that the energy transition is progressing,” DNV said in a news release. “The energy mix is moving from a roughly 80-20 mix in favour of fossil fuels today, to one which is split equally between fossil and non-fossil fuels by 2050. In the same timeframe, electricity use will double, which is also at the driver of energy demand only increasing 10%.”

Falling emissions

Global energy-related CO2 emissions are expected to fall 5% by 2030, compared to 2023, as solar and wind production rises. The outlook shows 17 gigatonnes (Gt) of CO2 emissions in 2050, a nearly 50% drop from 2024 levels.

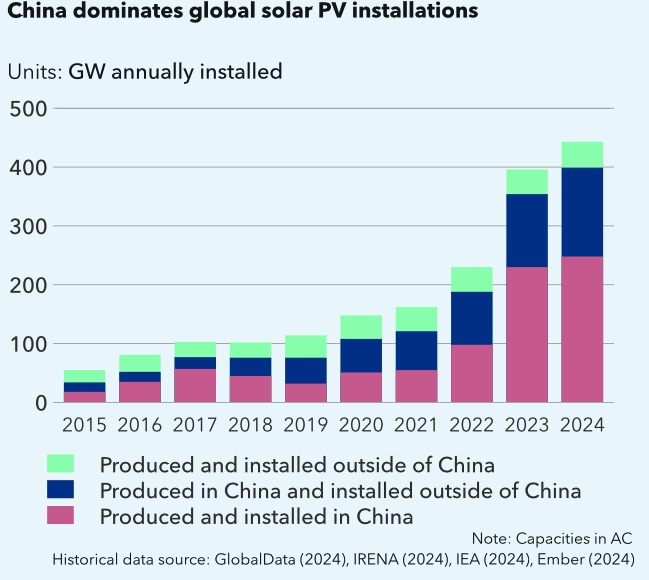

The drop is mainly attributed to the surge in solar photovoltaics, which Alvik said added a record-setting 400 gigawatts (GW) of new installments last year. Solar capacity has grown as costs have fallen.

“It’s actually a year-on-year growth of 80%. And though the growth at the moment is dominated by China, it’s happening everywhere,” he said.

Batteries are also among the top performers, strengthening both the electric vehicle (EV) market and improving the reliability of grids. By 2031, DNV forecasts half of all vehicles sold worldwide will be electric. That would be up from about 12% last year.

In the U.S., the Department of Transportation reported that 1 million EVs were sold in 2023 out of a total of 15.5 million total vehicles.

Having endured a rough patch in the past couple of years, more wind capacity—both offshore and onshore—is also expected to contribute to lower emissions.

“These two technologies will see a year-on-year growth of 8% from now until 2050,” he said. “And offshore alone will see a 12% year-on-year growth through to 2050.”

North America electrified

In North America, the electricity grid is forecast to almost fully decarbonize by 2050, said Matt Lockwood, vice president of strategic market areas and accounts at DNV. Generation is dominated by natural gas today.

“In the future, 95% of the new projects, about 2.5 GW of projects that are requesting access to the electric grid are solar, storage and wind,” he said.

Energy demand is forecast to fall amid electrification and energy efficiency gains, he added.

“Energy efficiency in North America, we forecast, will cause about a 33% drop in energy consumption per capita over our forecast period,” Lockwood said.

The signs are already present.

“If you look at data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration, for example, from 2009 to 2023, overall energy consumption dropped by 6% across residential, commercial and industrial sectors. And at the same time, the overall efficiency of that system, which is comparing overall energy losses to total energy use, increased by 9%. … Electrification shifts demand to electricity, and those additions are largely being met by renewable generation.”

Hydrogen slows

In the report, DNV Group President Remi Eriksen pointed out that DNV revised down its long-term forecast for hydrogen and its derivatives by 20% since last year.

“Without a meaningful carbon price and/or direct market-stimulating support, hydrogen will struggle to scale and move down a cost-learning curve,” Eriksen wrote. “The same holds true for CCS [carbon capture and storage] where our current forecast is that investment in CCS during our entire forecast period will be less than the amount invested in solar and wind in 2023 alone.”

DNV revised up its CCS forecast, though only 2% of global emissions will be captured in 2040 and 6% in 2050.

Alvik added: “Hydrogen is never the first choice. The first choice is always direct use of electricity where you can.”

Hydrogen still has an important role to play in reducing emissions in the heavy transport sector—maritime and aviation. “Here we see a strong growth of hydrogen. But starting a little later than what we thought. In aviation and shipping, it’s mainly hydrogen derivatives like ammonia and methanol. But in the industry, it’s pure hydrogen.”

Fossil fuel phasedown

Fossil fuels’ share of the global energy mix is forecast to fall, dropping from about 80% today to 50% by mid-century, starting with coal reductions everywhere except India over the next decade, DNV predicts.

Oil is expected to plateau in the next few years before steadily declining 35% over the next 25 years as internal combustion engines are phased out, Alvik said. Natural gas—considered an energy transition bridge fuel—is increasing slowly but is expected to plateau after oil.

“Even though renewables are already competitive with fossil-fired electricity in most places, we forecast that it will be many years—well beyond our forecast period—before low- and zero-carbon energy sources dislodge fossil fuels from the broader energy system,” DNV said in the report.

Even as fossil fuels’ share in the energy mix declines, DNV predicted its use in non-energy employments will continue.

“Today, 14% of the world’s oil, 10% of the gas and 1% of the coal is used for feedstock in plastics, petrochemicals, asphalt and similar products. This fossil fuel is not burned and does not cause direct emissions. As the use of fossil fuel for energy declines towards 2050, the non-energy share will grow.”

China, China, China

Cheaper available technologies speed the global transition, but that is not always embraced when the technologies are coming from China. The country dominates the world in solar panel production, making all but 10%, backed by cheap labor, low interest rates and government policies.

“The sum of this is making Chinese technologies very competitive at the moment and it enables the transition elsewhere,” Alvik said. But this is not embraced everywhere, including in Europe and the U.S., where national economic and security concerns have led to the tariffs and regulations that reduce reliance on a single vendor.

“When you start with reshoring manufacturing to Europe or Americas, or you want to deviate from China as the sole single source of supply, this comes at a cost,” he added. “And we do see that the technologies become more expensive, at least for a while, and the transition comes slower due to this, at least temporarily.”

Carbon costs needed

The report also pointed out that while market forces are effective in promoting uptake of renewable electricity and EVs, energy policy is needed to help address costly and complex technology in other sectors.

“A cost on carbon is needed to achieve sufficiently rapid emissions reductions,” the report states. “While the U.S. follows an incentive-based approach to promote renewables and clean energy uptake, the lack of disincentives results in persistently high emissions.”

Eriksen said the Paris Agreement calls for mission-oriented energy transition approach, not one simply reliant on market forces.

“While the transition is now finally starting, its downwards trajectory is too slow because enabling policy is too weak,” according to DNV. “In this outlook, we quantify the many efficiencies gained from a doubling of electrification globally in the next 25 years. These efficiencies result in a very large cumulative benefit that should give policymakers justification to tackle the difficult hard-to-electrify sectors while doubling down on renewable technologies, including much-needed short-term support for offshore wind.”

Recommended Reading

Enchanted Rock’s Microgrids Pull Double Duty with Both Backup, Grid Support

2025-02-21 - Enchanted Rock’s natural gas-fired generators can start up with just a few seconds of notice to easily provide support for a stressed ERCOT grid.

ADNOC Contracts Flowserve to Supply Tech for CCS, EOR Project

2025-01-14 - Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. has contracted Flowserve Corp. for the supply of dry gas seal systems for EOR and a carbon capture project at its Habshan facility in the Middle East.

McDermott Completes Project for Shell Offshore in Gulf of Mexico

2025-03-05 - McDermott installed about 40 miles of pipelines and connections to Shell’s Whale platform.

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Three Weeks

2025-03-28 - The oil and gas rig count fell by one to 592 in the week to March 28.

Equinor’s Norwegian Troll Gas Field Breaks Production Record

2025-01-06 - Equinor says its 2024 North Sea production hit a new high thanks to equipment upgrades and little downtime.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.