The U.S. is producing and exporting record volumes of oil, natural gas and NGL with an anticipated surge in domestic power demand from data centers, all of which is expected to require continued midstream infrastructure growth.

The rising domestic demand for natural gas-fired power and for international liquids and gas comes at a time of ongoing industry consolidation and amid a challenging regulatory and permitting environment.

The end result means fewer companies building more pipelines, processing and treatment facilities, storage and export terminals and LNG facilities while carefully navigating evolving approval processes—much easier said than done.

“The fundamentals are that both oil and gas are still a critical component of any energy policy and of our infrastructure,” said Greg Ebel, president and CEO of Enbridge, in an interview with Midstream Business. “That wasn’t necessarily a popular view a couple of years ago.”

“This is about energy evolution,” Ebel said, who heads North America’s largest midstream player. “As a result, the midstream sector is a critical component. We seem to keep hitting increasingly new records of utilization. It’s always a challenging business—all infrastructure is—but we’re still building pipes and processing facilities and export facilities at a quicker rate than people are able to do, say, electric transmission lines.”

The two big growth drivers right now are electricity and exports, executives and analysts said. And natural gas-fired generation makes up about 45% of all U.S. and North American electricity, necessitating more midstream buildout.

Because more U.S. natural resources are being shipped overseas and because of more associated gas and NGL, especially in the booming Permian Basin, the varying commodities also are more interconnected than ever before, said Rob Wilson, vice president of product for East Daley Analytics.

“There’s more need to look at all three commodity streams—gas, crude and NGLs—as opposed to looking at them independently,” Wilson said. “You’ve been able to get away with that, and you can no longer do that.

“In almost all three cases, the marginal barrel of growth is almost entirely going to international markets,” he continued. “One exception would be with the increase in demand from data centers domestically. But, when you think about gas, we’re seeing significant exports of LNG.”

“When you look at ethane, we see a significant amount of activity around exports. We’re seeing it with propane. We’re seeing it to a lesser degree with crude, but there is still some activity “there as far as [adding and expanding] export terminals.”

The clearest example is the Waha wackiness in the Permian with the surge in associated gas production, takeaway constraints waiting for the long-haul Matterhorn Pipeline to come online and exasperation stemming from maintenance downtime with the Permian Highway Pipeline and other systems. The end result has been occasionally negative Waha Hub pricing in West Texas, as well as constrained activity from stranded gas fears.

“Waha is insanely more volatile today than it was two years ago,” Wilson said. “That could be a microcosm or somewhat of a canary in the coal mine for what’s to happen on a broader scale as we open up our markets more and more into international markets.

“It’s really those three things: The markets are linked. They’re significantly more exposed to growing international demand. And then, the scale of growth will lead to more price volatility.”

Gassing up for more power

U.S. power demand has held relatively flat for nearly two decades even as the population has grown because of increasing efficiencies from light bulbs and more.

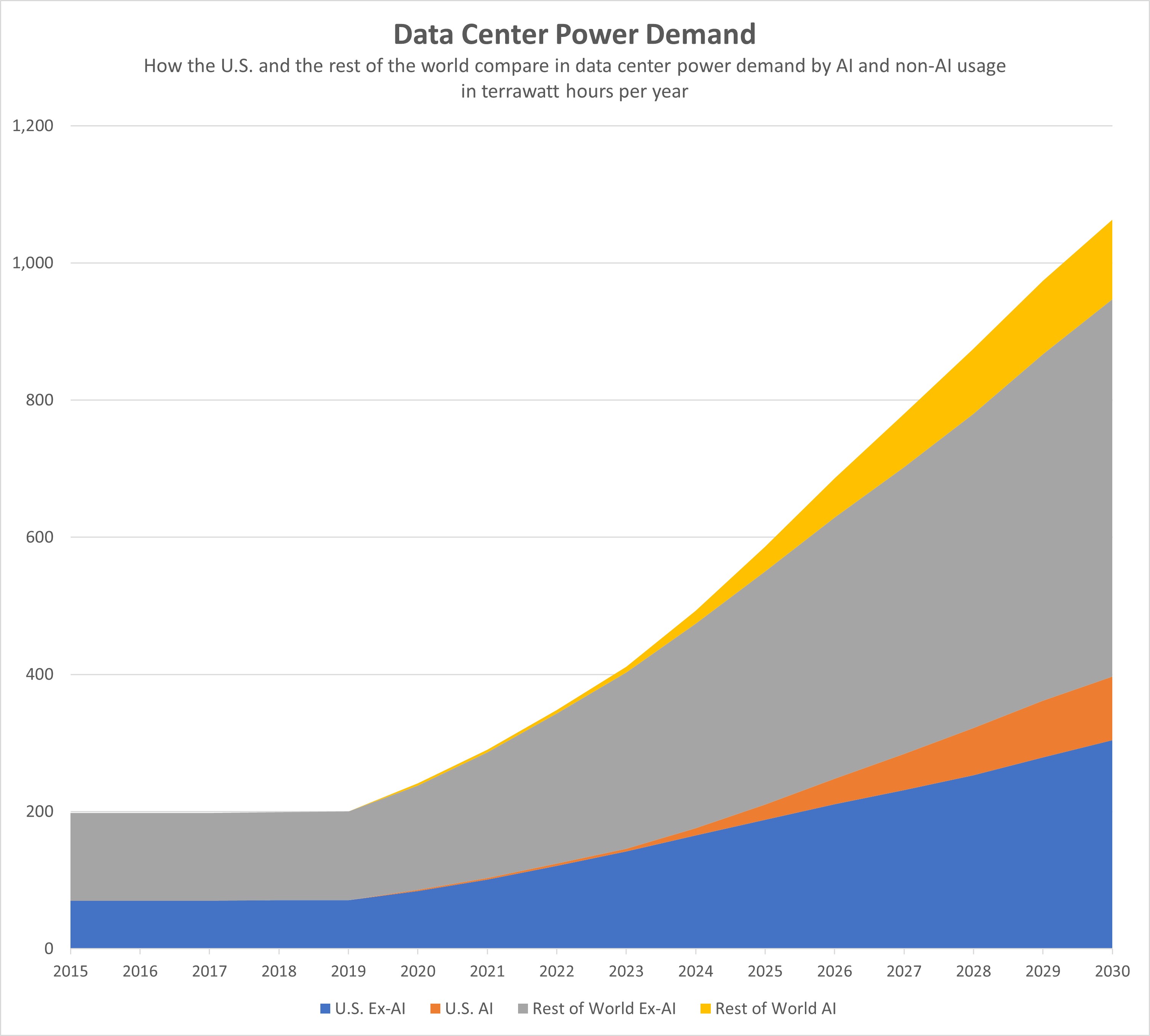

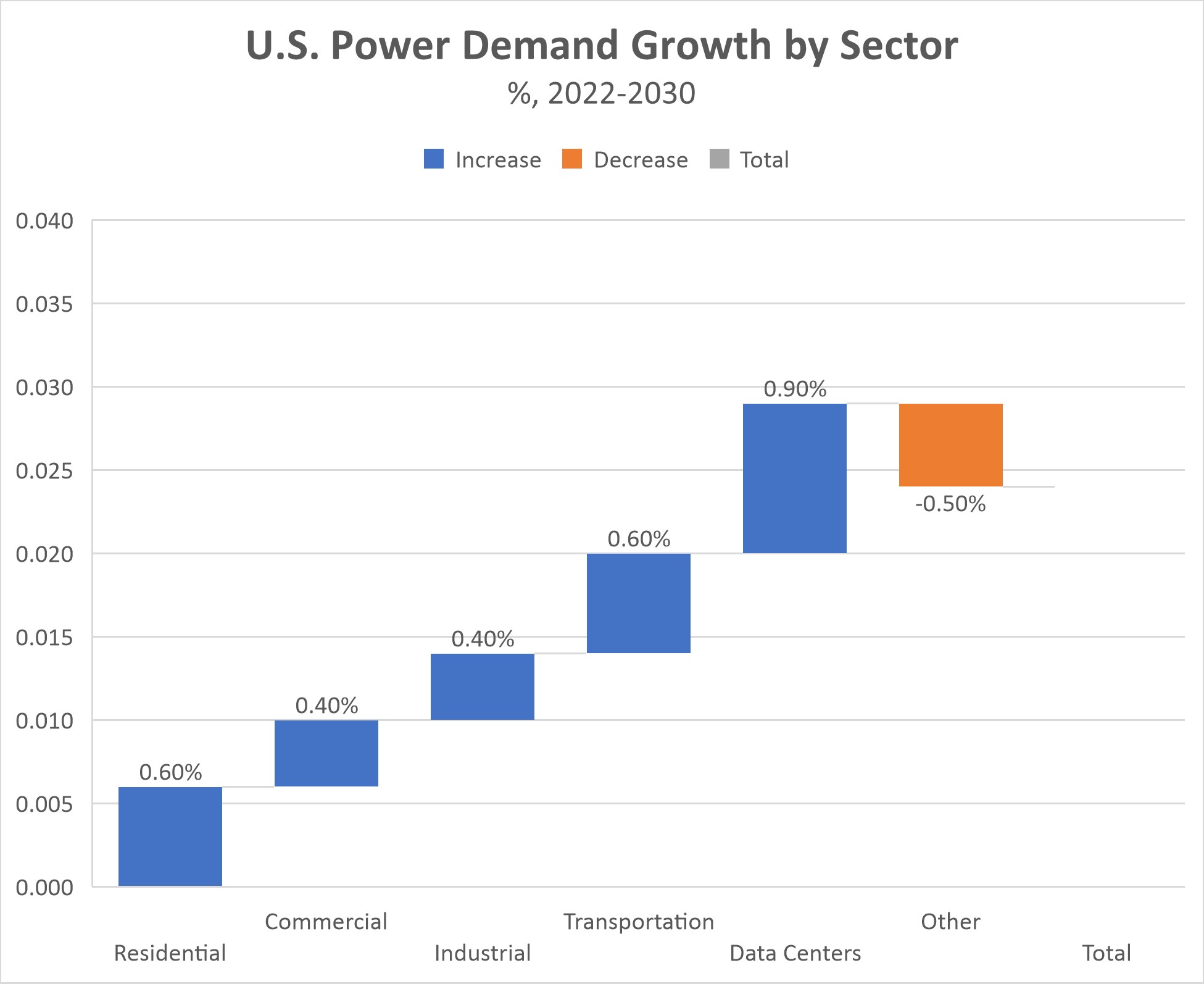

That’s set to change now from artificial intelligence (AI) and data center demand and the slow-but-steady electrification of transportation, although by how much is certainly up in the air. Forecasts of domestic demand range from almost 2% to nearly 5% by 2030. Those don’t seem like huge numbers, but they represent big jumps in required power generation.

A Goldman Sachs Research report from May projects a 2.4% jump in U.S. power demand between 2022 and 2030, including nearly 1% just from data centers for AI and more—a 165% surge in data center power demand.

(Source: Goldman Sachs Research, U.S. Energy Information Administration)

The bottom line is this will require a lot more natural gas, regardless of how much more wind, solar and battery power come online.

Also, this anticipated spike comes during the same timeframe when U.S. LNG export capacity is expected to almost double. That’s a lot more U.S. gas being consumed domestically and abroad.

“It’s just astronomically taken off. It is a bit surprising how fast that’s gone,” said Sital Mody, president of Kinder Morgan’s natural gas pipeline group. “There’s discussion across the board on where to site [data] facilities. We’re having more discussions directly with data centers themselves, utilities, power providers.”

“It’s early in the process,” he added. “We absolutely are trying to see how the ultimate market is going to evolve. We do know the demand is there. They’re looking for clean power, but the reality is how you get that 24/7 reliability. Natural gas is going to have to be part of the story.”

New power and LNG demand will both come online in chunks and not always as quickly as anticipated. More pipelines, gas storage and transmission infrastructure will all be needed, and some aspects will be easier than others, which will all contribute to temporary volatility.

The midstream sector is set to benefit, especially those with strong gas footprints, Mody said. But it won’t be seamless.

“If everyone is calling on their capacity and you have a need, then you don’t have enough pipeline capacity. That’s really going to come to manifest itself sooner as all this LNG demand comes on here in the next year or so,” Mody said. “You’re going to see the volatility. We expect to see it. These aren’t predictions. This is kind of how we see the market coming together at a macro level.”

Ebel thinks a lot of prognosticators are underestimating the challenges for permitting and building new electric transmission from state to state.

“I have no doubt that the power demand is going to come. The question is how quickly is that? That’s why companies like ours and others in the midstream sector are careful how they do this,” Ebel said. “It’s about three years in the best jurisdictions to get an interconnect for electric transmission, and the laggards would run six [years], seven years to get interconnected. If that’s the case, then it’s going to take a little bit of time for all these data centers to actually get access to the power they need.”

This emphasis is partly why Enbridge recently spent $14 billion to dramatically expand its gas utility business by acquiring the East Ohio Gas Co., Questar Gas and the Public Service Company of North Carolina—all from Dominion Energy.

In the meantime, the immediate emphasis is on expanding gas takeaway capacity from the Permian. The 2.5 Bcf/d Matterhorn Pipeline to Houston is now online and slowly ramping up, which alleviates a lot of woes.

Kinder Morgan is strongly weighing an expansion of its Gulf Coast Express Pipeline (GCX) from the Permian to the Texas hub in Agua Dulce near Corpus Christi.

“GCX, from a timeline standpoint, has probably a little advantage in terms of how fast it can get to market given the nature that it’s just compression expansion,” Mody said. “But there is absolutely the need for a pipe, too.”

That new pipe is coming in the form of the recently announced Blackcomb Pipeline, which would come online by the end of 2026, carrying 2.5 Bcf/d 365 miles from the Permian to Agua Dulce.

The WhiteWater Midstream-operated Blackcomb project also involves MPLX, Targa Resources and Enbridge, the latter of which owns a 13.3% stake.

“All these projects are competitive, so they stay in the quiet zone until you’re confident you’ve got contracts signed up and you can move forward,” Ebel said, praising the joint venture (JV) and the pipeline project. “It’s exactly the kind of thing that we were looking for.”

WhiteWater and its partners also teamed up earlier this year with Enbridge for the initial JV that aimed to connect the Whistler Pipeline from the Permian with Enbridge’s Rio Bravo Pipeline project that would stretch from Agua Dulce to NextDecade’s Rio Grande LNG project in Brownsville at the southern tip of Texas along the Gulf of Mexico and the Mexican border. Blackcomb is designed to take a similar route to Whistler.

And Energy Transfer is still pushing forward with its proposed Warrior Pipeline from the Permian to East Texas, which, if built, would carry at least 1.5 Bcf/d to the Fort Worth region, potentially serving different markets.

Of course, building long-haul pipelines is more challenging than ever. It’s nigh impossible on the East Coast—the recently completed Mountain Valley Pipeline took a decade to finally cross the finish line. But they’re not even easy to build in Texas, as recently shown by Kinder Morgan overcoming multiple right of way and eminent domain legal challenges in the Texas Hill Country for its now-operating Permian Highway Pipeline.

“Realistically, you can’t take shortcuts in your planning process. You need to reach out to all the stakeholders. You need to be reasonable,” Mody said. “Ultimately, when folks aren’t reasonable, you’ve just got to let the process play out and you’ve got to be patient. You can’t overcommit to something without thinking through all the consequences.”

“I think our legal and regulatory teams are some of the finest in the industry. How many challenges did we have? We had 14 challenges, and each one of them we overcame legally.”

Overall, Jamie Welch, president and CEO of Kinetik, is bullish but realistic on natural gas demand and building more infrastructure amid his gathering and processing empire in the Permian’s Delaware Basin.

“We’ve seen significant growth on the generation side. We’re seeing it going through the LNG side. And that’s obviously expected to continue. I remain constructive on gas,” Welch said. “I do not think gas is a $5/MMBtu commodity. I think we have such an abundance of gas that we will remain $3 or $4, and that’s OK, and I think everyone wins.”

Processing problems

Kinetik has quickly grown into the top Permian midstream pure play through mergers and organic growth.

So, Welch is both long-term optimistic but temporarily frustrated with Waha Hub pricing, takeaway issues, and stunted demand from more mild winter and summer seasons.

“We’ve never seen Waha this bad for this long. It’s bad,” Welch said. “It has significant negative economic value, and the duration that this has remained has, I think, stunned producers. They just don’t know what to do, because no one quite saw this.”

Granted, the still-young Kinetik has a nearly $3 billion market cap, earned $109 million in second-quarter net income, and recently acquired the Durango Permian gathering and processing assets in New Mexico for $765 million.

But Welch sees challenges—as well as opportunities—ahead in the Permian.

“I think processing remains tight, treating is very tight. As we continue to see different zones exploited by our customers—in those which have greater ranges of gas quality—that treating and blending is really critical and are areas that have for a long time been overlooked,” he said. “You can agree to something by contract, and you can build something that’s slightly different where you think it should be, but you couldn’t accommodate 5% CO2.”

Kinetik is focusing on moving gas out of New Mexico, especially Lea County, where there are more elevated levels of CO2 coming out of the production. “We’ve been a net beneficiary while others have struggled, and that means gas has been diverted our way versus going to other gathering and processing companies,” Welch said.

One thing that is catching the industry off guard is the different grades of gas coming out of the more exploratory benches in the Delaware, he said. Kinetik and others are rushing to quickly adapt and take advantage.

“When you look at Lea County and the preponderance of the development and drilling activity there, you’ve got a lot of Avalon [Shale] and Third Bone Spring that have much, much higher levels of CO2,” Welch said. “We discover these things as we go. There is no wonderful blueprint. We basically roll along with it, and we learn from the process of discovery. The process of discovery is the most important element in the midstream evolution. We understand what we’re seeing, and then we adapt. I think that’s sort of underestimated.”

Likewise, there are more challenges with a lot of Permian gas and higher nitrogen levels that make processing and liquefaction more cumbersome.

“One key issue on the LNG side is nitrogen. How are we going to handle that as we move forward?” Mody said. “From an infrastructure standpoint, how do you handle the nitrogen needs of the LNG facilities, given the high concentration of nitrogen out of the Permian?”

That also means building more gas infrastructure out of the Eagle Ford and Haynesville shale plays to continue serving the surging—if briefly slowed—LNG demand.

As such, Kinder Morgan is building the Evangeline Pass expansion project in Louisiana for Venture Global’s Plaquemines LNG project. And there are the pending Texas Louisiana Expansion and the South System Expansion 4 pipeline and processing projects moving Texas gas to LNG hubs.

“You’re going to need all the basins to meet the demand here,” Mody said.

Kinder Morgan also is moving more gas to Mexico for planned West Coast LNG, and to the western U.S. to serve growing domestic demand and anticipated data centers.

Newer processing plants can extract more ethane from the production stream. That has contributed to more NGL conversions along the midstream systems. Enterprise Products Partners recently converted its Seminole Red Pipeline to NGL service from the Permian.

Likewise, in the Bakken, Kinder Morgan is now switching its Double H Pipeline from crude oil to NGL service. In North Dakota, this is related to growing gas-to-oil ratios (GORs) in the Bakken, Mody said.

“This is another example of us looking at the macro and seeing an opportunity to help our producers extract incremental value on their side by not having a limitation on the NGL side,” Mody said. “I think you’d be surprised by the GORs. The need for NGL and gas is probably going to go up more than the existing infrastructure out there, even after these expansions.”

While most of the crude midstream buildout already occurred in the Permian and Bakken in previous years, East Daley analysts warned that crude constraints could return sooner than anticipated in the coming years.

“Where the market might be overlooking things a little bit is on the crude side,” said Ajay Bakshani, East Daley director of energy analytics. “We have Permian crude egress tightening and, as far as liquids go, things tend to tighten up out of nowhere. It’s an area the market still hasn’t paid much attention to in a while.”

“There’s a couple of capacity expansions that I think could still be on the table, but I wouldn’t be surprised if we see another [crude] long haul as well.”

In August, Enbridge announced the 120,000 bbl/d expansion to its Gray Oak Pipeline. Gray Oak is the 850-mile crude long haul connecting the Permian to Enbridge’s Ingleside Energy Center, which is the largest crude oil storage and export terminal by volume in the U.S.

Enbridge also is exploring more capacity expansions along its massive Mainline network stretching from the Canadian oil sands down to the Texas Gulf Coast.

“We’re in discussion about additional pipeline capacity coming in around 2027 for our Canadian customers that are either trying to get to refineries in the United States or getting all the way to the Gulf,” Ebel said.

Meanwhile, the Double H project could inadvertently trigger some crude egress issues from the Bakken, Bakshani said, who noted that Energy Transfer’s major artery, the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), is almost 90% utilized.

“If you asked a year ago if that was going to be the case, I probably would’ve said no,” Bakshani said of DAPL. “But now that pipe might be full, and we’re seeing a surge in Bakken production as well. There are going to be infrastructure issues across most commodities.”

There are crude activity upticks in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin and in Utah’s waxy Uinta Basin that need more takeaway capacity, too, he said. And it’s not just for oil. Kinder Morgan, for instance, just pushed forward with the $263 million Altamont Green River Pipeline project in the Uinta for additional gas egress.

Financing some of these major pipeline projects can be difficult. But one solution is the growing trend of more and larger JVs to finance them, such as with the new Matterhorn, Blackcomb and Rio Bravo projects.

And JVs can invariably lead to more dealmaking, especially in a midstream sector that needs more consolidation to thrive, according to East Daley.

After record-breaking periods of ongoing upstream M&A, the midstream sector is getting busy, too.

“We’re still very much in a consolidating period right now,” Wilson of East Daley said. “I think that has another 18 [months] to 24 months to it.”

Consolidation concentration

As with the E&Ps, the midstream space is consolidating with a very Permian-centric mindset. But the dealmaking is not West Texas exclusive, either.

Greenfield pipelines are harder to build, making existing pipe in the ground more valuable and ensuring that acquisitions represent the strongest growth option. The trend seems to be for the biggest pipeline operators to buy up more gathering and processing players to provide more full-service offerings to their customers.

The big buzz phrase now is “from the wellhead to the water.” As Ebel said, “It’s being able to competitively put a full path from where the product is produced to actually where it’s ultimately being either shipped offshore or being used in the country.”

“We’ve definitely seen the maturation of midstream companies,” Wilson said, adding that the industry is essentially in the middle of an acquire-or-be-acquired spree. “If you don’t own the full value chain going forward, your long-term strategy is in question,”

The biggest names remain Enbridge, Enterprise, Energy Transfer, Phillips 66, MPLX, Kinder Morgan, Williams Cos., Targa and ONEOK—the latter three of which have especially seen their market cap values soar of late. Anyone else, including even some of the aforementioned, could be scooped up, Wilson and Bakshani said.

“There’s a lot of decent-sized Permian G&P systems that are available,” Bakshani said. “We’re looking at when they were invested in, when these PE companies are probably trying to exit, which is about now. So that’s mostly in the Permian.

“I think one of the drivers is going to be on the G&P side and capturing that barrel at the wellhead.”

Some of the recent deals include Energy Transfer buying Lotus Midstream, Crestwood Equity Partners and WTG Midstream. Energy Transfer’s Sunoco also acquired NuStar Energy.

Otherwise, Enterprise is buying Piñon Midstream in the Permian, Phillips 66 is acquiring Pinnacle Midstream, ONEOK is scooping up Magellan Midstream and more NGL assets from Easton Energy, and upstream gas leader EQT is rolling up Equitrans Midstream.

The most obvious publicly traded acquisition targets, Bakshani and Wilson said, are EnLink Midstream, Western Midstream and, yes, Kinetik, even though it just expanded with the Durango deal. As a side note, producer Occidental Petroleum owns a large chunk of Western, and Oxy is eyeing divestments. Oxy recently sold some Western units for about $700 million.

Kinetik’s Welch is not blind to that portrayal. In fact, he embraces it.

“We’re pragmatists. We’ll continue to be a catalyst for growth—whether it’s organic or it’s acquisitive—until such time as we are no longer tasked with that role, and we are now just being swept up by a much larger competitor,” Welch said. “I think the realization we have is that time is finite and that we won’t be around too long, and then we will fit into someone else’s plans.”

“I think the need for consolidation remains because it creates capital discipline as we’ve seen. On the customer side, it’s important to have that growing capital access and scale on the midstream side. That’s just the reality. That’s just an evolution of the market. They realize the multiple services that larger companies can offer—the wellhead-to-water opportunities.”

Kinetik has grown rapidly—it was created through the combination of EagleClaw Midstream and Altus Midstream—but not in comparison to the three Es—Enbridge, Enterprise and Energy Transfer.

“We are literally a minnow; we are like fish food,” Welch said. “We’re going to continue doing what we’re doing until we’re told to stop, and that’s all you can do.”

But Welch agrees that the private players also will go the way of the dinosaurs. The end of an era is on the horizon.

“The midstream sector remains probably in just about the healthiest place it ever has because balance sheets are much improved, leverage ratios are down, there’s much more discipline on distribution growth, and there’s not the proliferation of lots of new management teams and lots of new IPO vehicles or public companies,” Welch said. “There are fewer customers, there are fewer real impactful basins, and there will be fewer competitors on the midstream side, and that’s just a fact of life.”

The private players can grow, but only in the short term because they lack the necessary growth capital. And the public producers are reticent to contract with them when they could be “here today, gone tomorrow,” Welch said.

The bottom line: “I think all of these private companies are going to be gone in two years.”

Recommended Reading

Origis Completes $415MM Funding for Texas Solar Project

2025-01-09 - Origis Energy’s Swift Air Solar project, which is currently under construction, will enter commercial production in mid-2025.

National Grid Agrees to Sell $1.7B Onshore US Renewables Business

2025-02-24 - The sale of National Grid Renewables to Brookfield comes as the utility continues efforts to streamline its business and focus on networks.

CarbonQuest Lands $20MM Funding for Carbon Capture Projects

2025-02-27 - The new funding is aimed at helping CarbonQuest achieve the lowest cost per ton in the carbon capture industry and improve system efficiency for North American customers.

Baker Hughes, Hanwha Partner to Develop Small Ammonia Turbines

2025-02-03 - Baker Hughes, in partnership with Hanwha Power Systems and Hanwha Ocean, aim to complete a full engine test with ammonia by year-end 2027, Baker Hughes says.

PE Firm Hy24 Commits $50MM to StormFisher Hydrogen

2025-02-11 - The funding, made via Hy24’s Clean Hydrogen Infrastructure Fund, will go toward StormFisher Hydrogen’s efforts to produce clean fuel in North America.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.