The 2.0 version of the Trump administration has the energy sector exuberant about the White House’s immediate declaration of a “national energy emergency” along with an executive order pledge to “unleash American energy.”

A more experienced President Donald Trump with a more loyal team surrounding him is wasting little time attacking the nation’s federal bureaucracy, but that convoluted web of bureaucracy can work to either streamline or impede the oil and gas industry at various points and under varying leadership.

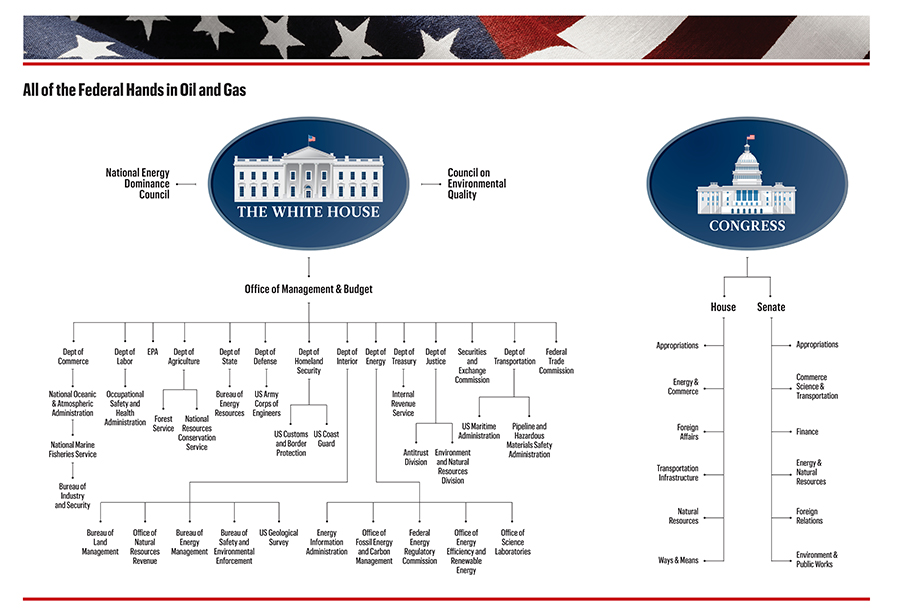

The domestic oil and gas upstream and midstream sectors are touched by close to 30 federal departments, divisions and councils, as well as at least a dozen congressional committees, not to mention federal and appellate courts.

Assigned with untangling the knots are Trump’s “dream team”—as dubbed by Harold Hamm, executive chairman of Continental Resources—of Energy Secretary Chris Wright, former CEO of Liberty Energy; Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, former North Dakota governor; and EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin, the former New York congressman. Burgum will oversee Trump’s new National Energy Dominance Council.

While the Department of the Interior and the Department of Energy touch the most aspects of oil and gas, there are a bevy of little-known but critical agencies and acronyms to know. Companies operating on federal lands often must work with the Department of Agriculture’s U.S. Forest Service, while offshore players deal with the Department of Commerce’s National Marine Fisheries Service, among many other agencies.

The Interior’s Office of Natural Resources Revenue is ONRR, pronounced like “honor,” while many, such as the Department of Justice’s Environment and Natural Resources Division, or ENRD, lack any fun pronunciations.

Dan Brouillette, Trump’s energy secretary from 2019 to 2021, has observed the bureaucratic mishmash from the inside and outside, recently leading Sempra Infrastructure until mid-2023 and then the Edison Electric Institute until late 2024.

“It does get confusing for some industry players, but certainly for the public itself,” Brouillette said in an interview with Oil and Gas Investor. “We can streamline a lot of processes, in my view.”

While bureaucratic nightmare scenarios certainly can exist, Brouillette does offer praise, in particular, for the energy and interior departments and how they usually balance each other.

“I think they work fairly well together,” Brouillette said. “I mean, I’m sure there are instances when there are disagreements, or you’ll have competing interests. But, nonetheless, I think they work well.”

What goes where and how

Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) handle the onshore and offshore leases, but the Energy Department’s scientific research on the shale and deepwater reservoirs plays key roles in the decision-making processes for lease sales, Brouillette said.

The DOE oversees the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management (FECM), the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE) and, most importantly, the Office of Science Laboratories and the 17 national labs, including Los Alamos, Oak Ridge and Sandia.

Early on, Brouillette worked as a pipe welder in his native southern Louisiana, and then he eventually became a congressional staffer, working in the House Energy and Commerce Committee. Under President George W. Bush, Brouillette joined the DOE as assistant secretary for congressional and intergovernmental affairs. In the Trump administration, he became deputy secretary and then secretary after Rick Perry resigned.

The scientists and career staff in DOE, DOI, EPA and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which is independent but part of DOE, tend to work in cooperation, Brouillette said.

“They have long histories. I think there’s a lot of respect amongst the agencies and amongst the senior players in the agencies,” he said. “It doesn’t mean that they don’t disagree from time to time. They absolutely do, but that’s what you want in the scientific arena.”

While a lot of the staff may work together, the energy companies typically see things differently and more cynically. They often need help navigating the patchwork, said Jack Belcher, principal at Cornerstone Government Affairs.

“It’s like a real web of entities that don’t really work well with each other and their priorities are not aligned with yours, usually,” Belcher said. “Sometimes you’ll need approvals from two or more in order to get whatever it is you need. It gets quite complicated, and things take a long time. It’s inherently inefficient.

“Federal agencies are set up with jurisdictions. Those jurisdictions are set by the way they were organized by Congress. And Congress has its own fiefdoms, and it likes to control certain things,” he continued. “Some of it has to do with turf wars. Over time, they develop their own personalities and quirks and characteristics that you have to understand.”

Offshore, companies often must engage with the Department of Defense, the U.S. Coast Guard, the Department of Transportation’s U.S. Maritime Administration and the Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Onshore, there’s also the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, FERC, Transportation’s Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) and more.

Everyone has to work with the Department of Labor’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the EPA’s Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act and Endangered Species Act, which has introduced energy companies to the dunes sagebrush lizard, the lesser prairie-chicken, the Rice’s whale and many other obscure and endangered species.

A lot of rules, programs and tax credits are going under review under Trump, Belcher said, from the EPA’s Methane Emissions Reduction Program (MERP) to credits like 45Q for carbon sequestration and more.

“What’s going to happen? We don’t know. They’re going through this review process. The president doesn’t know, and he changes his mind a lot,” Belcher said. “We know that. He’s not afraid to change his mind. There’s an opportunity for industry to provide feedback and make its case. And then there’s going to be litigation.”

Interpreting executive orders and reforms

Brouillette is most eager to see reforms enacted with National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) processes to determine if energy projects have significant environmental impacts.

“The NEPA process is just out of control,” Brouillette said. “In today’s world, every agency wants to do an environmental impact statement. You go to FERC, they want to do one; you go to EPA, they want to do one; you go to Interior, they want to do one. In my view, it’s redundant, it’s bureaucratic and it’s expensive. That’s one of the reasons why consumers have not enjoyed the benefit of the increased production of oil and gas here in the United States over the last four years.”

He contends the DOE could handle the NEPA reviews for every agency. The nation needs to expedite infrastructure for pipelines, gas-fired power generation, data centers, LNG export hubs and more.

“Pipelines are critical and are sort of the weakest link in the chain right at the moment in the United States. It’s not the production elements, but it’s actually the infrastructure elements. We know full well how to produce molecules. That’s how we’ve become the largest producer in the world,” Brouillette said. “Our challenge today is actually getting the product to market, developing enough pipeline capacity to get the natural gas to the oceans, to get the oil to the markets. That’s been our challenge, and that leads back to the permitting challenges that we have here in the United States.”

The White House “lost a lot of time” in Trump’s first administration learning the ins and outs of government, but now Trump is operating at a “blistering pace,” Brouillette said.

“I think there’s a world of difference,” he said. “The president, when he was elected in 2016, had a wealth of business experience, and he understood very clearly what he was elected to do, but he wasn’t quite as comfortable in the governmental space.”

Brouillette also sees Trump’s declaration of a national energy emergency as “absolutely necessary,” especially for encouraging natural gas production and gas-fired power plant construction instead of just wind and solar.

“As we think about the demand coming on with AI data centers, increased industrial loads, we are very dangerously short of electricity generation,” he said.

When it comes to Trump, the challenge is often differentiating between what’s real and what’s rhetoric. The key is interpreting between Trump’s “signal versus noise” in his executive orders and language, and where they cross over on everything from energy production to data center construction, said Jamie Webster, non-resident fellow at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy.

“Some of the executive orders look like really clear signals, but many of these are not self-implementing. Some of them are already kind of in the system,” Webster said.

An executive order, “Unleashing American Energy,” is a clear signal for the industry, but what it will accomplish is less clear. The industry wants high oil and natural gas prices—but not too high—while Trump wants to bring prices down for consumers. And oil and gas producers won’t want to produce more in low-price environments.

“I think there’s a lot of uncertainty that is out there, and we’ll continue to try to figure that out,” Webster said. “But, what’s pretty clear to me, I think the longer-term trend and focus is going to be on lower prices because that has a lot of positive economic implications for the United States.”

What also is clear is the short-lived, Biden-era LNG pause is over, although the timeline for speeding up permitting is murky. And Trump is already pushing for new exploration and production on federal lands and waters, as well as in Alaska, including Alaska LNG in a potential partnership with Japan.

Already, FERC is citing Trump’s executive orders to move past judicial hindrances on NextDecade’s Rio Grande LNG and Glenfarne Group’s Texas LNG projects. So, the orders are clearly not without some teeth.

Even if U.S. production ticks up more slowly under Trump, he can still “declare victory” because volumes still rose, Webster said.

Trump also is moving with orders to ramp up pressure and potentially sanctions on Iran and Venezuela, which ultimately could remove more crude from the markets and increase prices, said Matt Reed, vice president of Foreign Reports. U.S. and Saudi barrels could fill the void.

“Sanctions could mean the difference between a supply surplus or deficit this year,” Reed said. “Remember, in his first term, Trump managed to slash Iran and Venezuela’s combined exports by over 2 million barrels a day compared to where they stand now.”

As such, Trump will lean more on Saudi Arabia and give them the benefit of the doubt, he added.

“There may be disagreements on policy, but the Saudis are going to focus on fundamentals, as usual, and Trump’s affinity for them should shield OPEC from any retaliation,” Reed said.

Talking tariffs

The other big uncertainty revolves around Trump’s love of threatening and occasionally implementing market-destabilizing tariffs.

He had already set and then delayed major tariffs on Canada and Mexico, while implementing smaller 10% tariffs on China, and then broader ones on foreign aluminum and steel. Then, on March 4, Trump's 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada went into effect, with duties on Canadian energy set at 10%.

Trump is more recently focused on planning reciprocal tariffs worldwide, from the European Union to India, which could easily upset global trading networks either in the short term or permanently.

“That is where the tension is,” Webster said. Tariffs raise prices, but they also incentivize more manufacturing within the United States.

“The real question is going to be, does he ever actually pull the trigger on these in a broad way, or is it used as a cudgel to get other things that would be useful for the administration, which is increased investment?”

Brouillette acknowledged the constant tariff threats create anxiety and disruption and the last thing that energy project developers want is unnecessary uncertainty.

Yes, tariffs on Canada could raise U.S. fuel prices, he said, but it’s not that simple.

“What options do the Canadians have?” Brouillette said. “Well, their primary export market for heavy crude is the United States. It’s not easy for them to build another pipeline to get their product to Asia or Europe. They’re not likely to do that. What they want to do is to maintain access to the U.S. market. So, what they’ll do in that instance is actually to lower prices to maintain access. In that sense, the tariffs are actually born by Canadians, not by Americans.”

Webster agreed that Western Canadian Select prices would have to be discounted, but he also sees U.S. pain as inevitable, too, which is why he does not believe Canadian crude will ever fall under tariffs, at least not for long.

“I don’t see how this is a long-term strategic option for the United States without significant economic difficulties,” Webster said. “So, I don’t see that happening on a long-term basis.”

And much of this will require some degree of patience to see what actually comes to fruition, Belcher said.

“A lot of this is symbolic. A lot of it is a message, and I think that’s very aligned with what Trump likes to do … create a momentum and support,” Belcher said. “These executive orders and tariff talks are kind of a first round with more granularity to come.”

Maybe the most important longer-term development could be how Trump’s new Energy Dominance Council shakes out under Burgum.

“It’s a nexus. It’s bringing federal agencies together to focus on national energy policy,” Belcher said. “That’s going to be interesting to see how that group works and if it can work through the rough edges where these departments kind of stick with one another.

“I think it’s a really exciting time. There’s no doubt about it. You can feel it when you’re talking to people. There’s a little concern about tariffs, projects, federal money. But, overall, it’s the sort of notion that the oil and gas industry is not a bad word anymore. It’s a return to government being pro-production.”

Recommended Reading

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.