Followers of the natural gas and midstream market couldn’t have missed the oncoming rise of LNG output on the Gulf Coast in Texas and Louisiana by the end of the decade.

The amount of U.S. LNG produced on a yearly basis is expected to more than double to 24.3 Bcf/d by 2028 from 11.4 Bcf/d in 2024, with the vast majority of new capacity coming from the Gulf. Major new pipelines, aimed toward the Texas and Louisiana coasts, have come online or are in the planning stages. The buildout has sparked national controversy, with environmental groups battling with businesses and the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in the courts.

Getting a little less attention: All of that extra gas will need a place to stay, and plenty of people in the business have taken notice.

It may seem counterintuitive that a lot of companies are publicly planning natural gas storage projects at a time when the prices have been low enough for many E&Ps to cut back on production. But the oncoming storage buildout, like any energy infrastructure, is not tied to immediate market shifts and instead a long-term bet made over the projected future jump in natural gas demand.

Midstream majors Williams Cos. and Enbridge have been acquiring storage over the past few years, according to an analysis by RBN. Some companies, such as Kinder Morgan, are planning to expand the facilities they already have, and some independents are planning to build the first salt dome storage project in the Houston area since 2008.

“Most of our storage is in these areas where LNG exports are going to be,” Alan Armstrong, co-CEO of Williams, told the audience at the Barclays Annual CEO Energy-Power Conference in September.

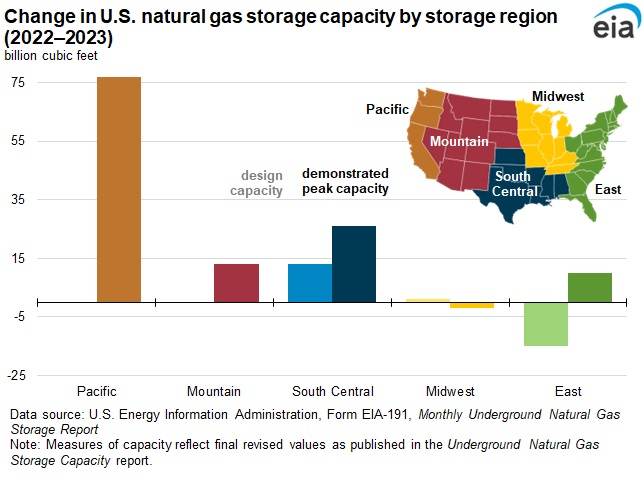

The overall level of natural gas storage in the U.S. has been flat for more than a decade, at about 4.6 Tcf, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Nameplate capacity in the U.S. dropped by 3 Bcf from 2022 to 2023.

However, demand for LNG and gas-fired power generation has been rising steadily in the 2020s and explosive growth in both sectors is expected well before 2030.

In the natural gas market, storage serves as a buffer, keeping supplies steady while demand jumps sporadically. LNG export terminals do not continuously offload product, and an electrical market heavily dependent on wind and solar tends to rely on gas as the steadiest backup.

“We think storage is going to be absolutely critical to both backing up renewables as well as being there for utilization as we start to build out the fleet of LNG exports here in the U.S.,” Armstrong said.

LNG facilities will usually not run at 100%, Armstrong said. “It will be coming off of that. And when you have that, you're going to put a lot of demands on both fast injection storage and storage that's close to where it can serve those facilities.”

Williams has experience in natural gas storage, thanks to its years of operating the 10,000-mile Transco pipeline. In January, Williams closed the $1.95 billion purchase of 115 Bcf of storage in Louisiana and Mississippi from an affiliate of Hartree Partners. The facilities included four underground salt domes and two depleted natural gas reservoirs.

Over the last three years, Enbridge has bought storage at either end of the Permian natural gas pathway: the Waha Hub near Pecos, Texas, and along the Gulf Coast. In April 2023, Enbridge closed a $335 million acquisition of the three-cavern Tres Palacios facility in Matagorda County, Texas.

RELATED

Heard from the Field: US Needs More Gas Storage

Brand new domes

Tres Palacios, the last salt dome cavern gas storage project on the coast, began service in 2008.

In 2024, the sponsors of two new salt dome projects aim to reach a final investment decision (FID) by the end of next year.

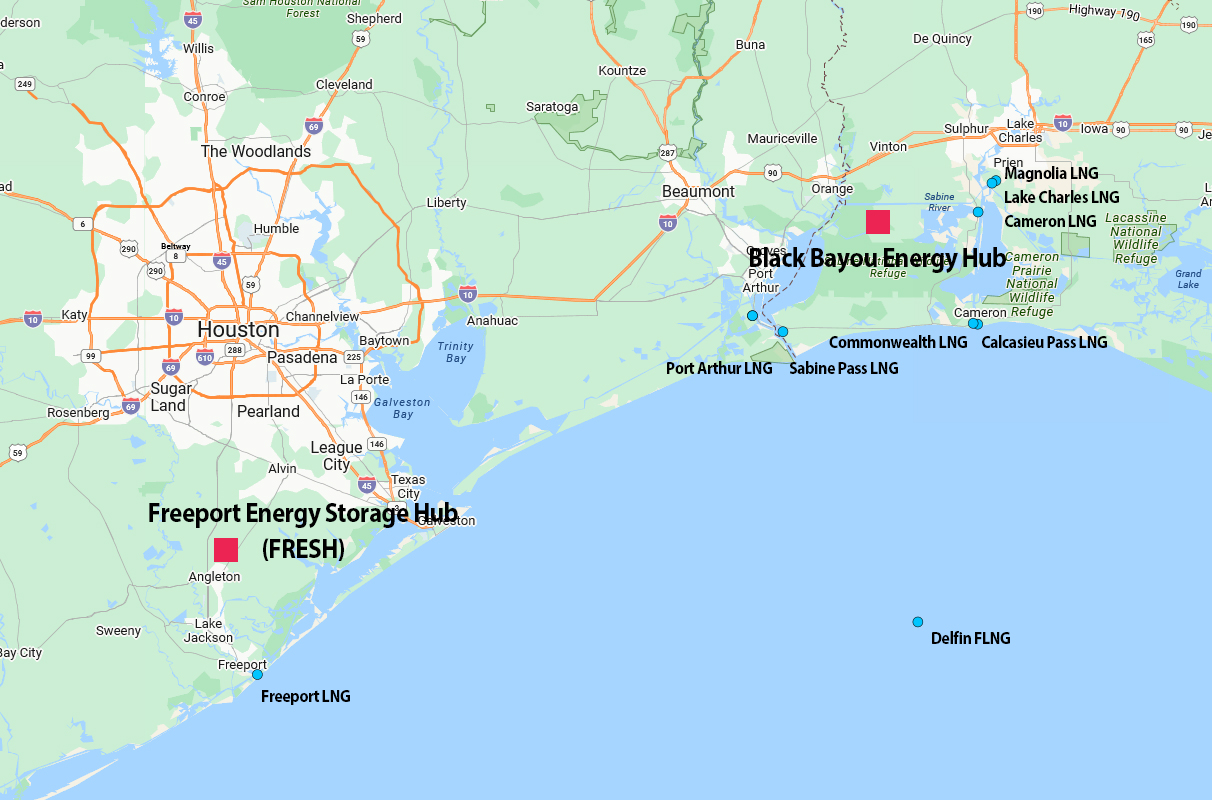

The proposed Black Bayou Energy Hub in Cameron Parish, Louisiana, would be halfway between some of the country’s major LNG facilities in Port Arthur, Texas, and Lake Charles, Louisiana.

According to RBN, the company held an open season for capacity in June. Thirty-five bidders requested 70 Bcf of space—more than four times the available capacity. After the season, the company announced it planned to double the scope of the project, from two salt domes to four.

On the other side of the Louisiana-Texas border, the Freeport Energy Storage Hub (FRESH) held an open season in October. The facility is also in the middle of several major natural gas pipeline pathways and the Freeport LNG terminal, already in operation.

FRESH plans to open two salt caverns with potentially 20 Bcf capacity in the first phase of the project, with additional capacity to be determined by customer demand.

Gulf Coast Midstream Partners, the company developing FRESH, hopes to reach FID next year. Black Bayou developers have targeted FID within a year or two, according to RBN. Both plan to start operations in 2028.

Building new salt domes is the most difficult sector of the storage market, RBN said in its analysis. Demand for storage is definitely up, but customers are usually going to be picky over where they ultimately put their product.

“While gas storage capacity is increasingly valued for its role in providing volume assurance and the opportunities created by high deliverability, that doesn’t necessarily mean storage values will be high enough to support the large-scale buildout of new facilities,” wrote RBN analyst Housley Carr. “Instead, the development of new storage capacity is likely to be very targeted— it will happen only where it has strong customer support and makes economic sense.”

Recommended Reading

SM Energy Marries Wildcatting and Analytics in the Oil Patch

2025-04-01 - As E&P SM Energy explores in Texas and Utah, Herb Vogel’s approach is far from a Hail Mary.

BlackRock’s Fink Calls for Reliable US Power Grid—Now

2025-03-31 - “That starts with fixing the slow, broken permitting processes in the U.S. and Europe,” Larry Fink, the co-founder, chairman and CEO of $12 trillion investment-management firm BlackRock Inc., told shareholders March 31.

E&P Highlights: March 31, 2025

2025-03-31 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, from a big CNOOC discovery in the South China Sea to Shell’s development offshore Brazil.

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Three Weeks

2025-03-28 - The oil and gas rig count fell by one to 592 in the week to March 28.

BP Earns Approval to Redevelop Oil Fields in Northern Iraq

2025-03-27 - The agreement with Iraq’s government is for an initial phase that includes oil and gas production of more than 3 Bboe, BP stated.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.