With the constant calls to reduce CO2 emissions, you could be excused for thinking the U.S. was already building one of the proposed solutions: A pipeline network to transport the greenhouse gas to deep wells for storage forever.

Clearly, that hasn’t been the case.

Some environmentalist groups say the projects will be ineffective. Some landowners have fought, successfully in one case, to kill projects before they began. The technical and economic issues required for a new type of line to deliver the project give some midstream companies pause.

However, at least two major interstate pipeline projects are on the drawing board in the Midwest, and the Louisiana state government recently completed a legislative overhaul to encourage the development of carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects that utilize the state’s advantageous geography.

There are no major U.S. pipelines that ship CO2 to permanent underground storage sites, but government and commercial actions over the first half of the 2020s has brought the new type of infrastructure closer to reality.

“Both 2023 and 2024 were big years as it relates to CCS,” said Colleen Jarrott, an energy attorney with the New Orleans firm Hinshaw & Culbertson.

On the table

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) granted Louisiana primacy (primary enforcement authority) over Class 6 wells at year-end 2023. The EPA categorizes Class 6 wells as the deep wells needed for CCS.

The primacy designation allows the state to come up with a regulation regime over the projects, which legislators created and Gov. Jeff Landry signed into law in June.

“We did go ahead and change a number of our regulations that we had on the books, both in the 2023 legislative session and again in 2024,” Jarrott said. “This most recent legislative session was to tighten up our regulatory scheme here in Louisiana to make sure that these projects are going to be safe and that they won’t negatively impact the environment.”

Critically for midstream companies, the legislation set up policies allowing for eminent domain in certain circumstances. The laws give pipeline developers more authority to secure rights to a pipeline pathway.

Louisiana is an ideal spot for developing CCS networks, Jarrott said. The state has one of the stronger energy industry sectors in the U.S., and its geographic make-up provides plenty of the “pore space” needed for permanent storage.

The idea is not new to the state. The legislature passed the Louisiana Geologic Sequestration of Carbon Dioxide Act in 2009, but it had little effect because CCS projects did not catch much attention at the time.

Over the last few years, however, companies have developed plans for intrastate CCS pipelines. About 30 carbon capture projects have been proposed in Louisiana, according to a tracker maintained by environmentalist group Clean Air Task Force.

Jarrott said it will take time for CCS pipeline and well developers to break ground on the proposals.

“Most folks are in the very preliminary stages of putting these projects together, which, as you can imagine, involve many steps before you even get to the construction phase,” she said. “They are probably about a year or more out from granting the first application just because they do have to do a very intensive review, and the state wants to get it right.”

Only two states besides Louisiana—Wyoming and North Dakota—have primacy for Class 6 wells, and both have major CCS projects in development.

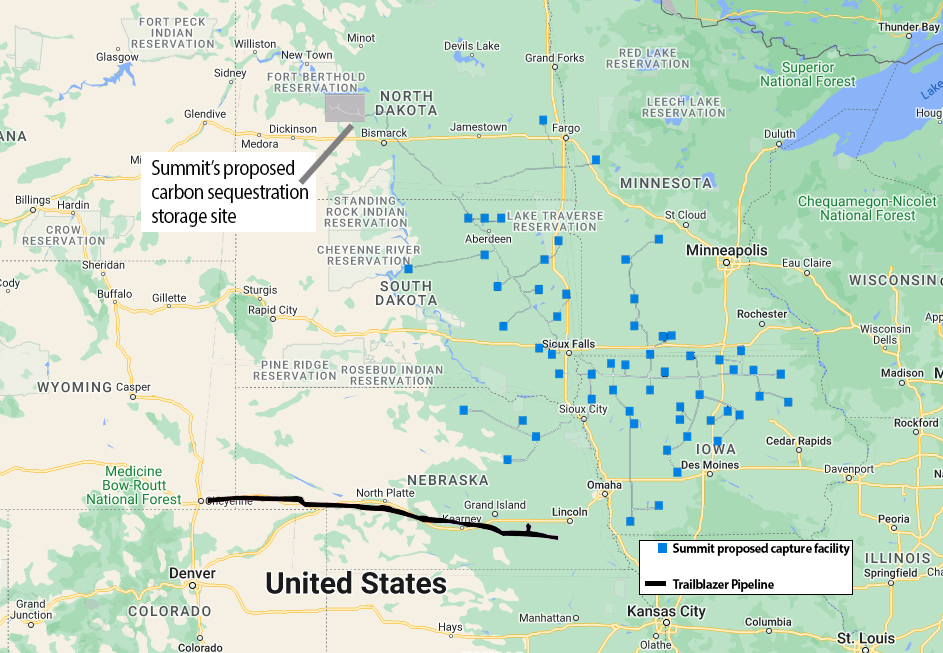

Tallgrass, one of the largest independent midstream companies in the U.S., plans to convert its 436-mile natural gas Trailblazer pipeline into a backbone for a regional network that would gather CO2 for well injection in Wyoming. The line would have a yearly CO2 capacity of 10 million tons/year and serve industries in Nebraska and Colorado, as well as Wyoming.

Tallgrass announced the plan after reaching an agreement with ADM in 2022 to take away CO2 from ADM’s corn-processing complex in Nebraska, according to analytical firm RBN. Tallgrass announced an open season for available capacity on Trailblazer in May.

As the midstream company with rights of way for Trailblazer, Tallgrass has a major advantage over other companies that are starting a pipeline network from scratch.

In Iowa, Summit Carbon Solutions is a company focused solely on creating a CCS network. Summit has planned a CO2 gathering network that will run through five states before depositing the gas in North Dakota. The company has planned more than 40 overall capture facilities, tied primarily to ethanol plants in the corn belt.

The project made news in June, when the Iowa Utilities Board granted Summit permission to build in the state. None of the other states along the line have given Summit permission to build, and opponents of the network have announced their plans to take the Iowa board to court, possibly delaying any further progress until next year.

The federal government has also become an active participant in CCS projects. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 increased federal spending on CCS to $4 billion in 2023. Most of the funds were for low-interest loans for eligible pipeline projects. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 also increased a federal tax credit for carbon capture from $50/ton to $80/ton for industrial removal and $180/ton for direct capture.

Old tech, new times

Carbon capture has been in use since the 1920s, when scrubbers were used to separate marketable gases in the oil and gas industry, according to a study published by the Environmental Law Industry.

In the 1960s, the energy industry discovered that CO2 could be injected into productive oil wells to enhance recovery. In 1972, Chevron put into service the world’s first large-scale CO2-enhanced crude recovery project in Scurry County, Texas.

The usage of CO2 to enhance crude production is widespread today. CO2 is the most commonly used material in the enhanced oil recovery process, according to the Congressional Research Service.

Jarrott said the CO2 networks currently in use to produce more oil are different from those that will permanently store gas underground. The infrastructure requirements are not as resilient and require a Class 2 well instead of a Class 6 well.

According to the EPA, Class 6 wells are usually about 1 mile below ground. The rock in the area needs to be porous enough to absorb CO2 like a sponge absorbs water. Proponents of CCS point to the potential a nationwide system could have in reducing the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced in the U.S.

In 2017, the EPA estimated that the U.S. has underground space to store 1 trillion to 4 trillion tons of CO2. The U.S. produced 6.3 billion tons of CO2 in 2022.

Unsure implementation

Despite the potential, the plans face challenges from several sectors of the public.

Last year, prior to the COP 28 Conference in Dubai, the International Energy Agency (IEA) threw cold water on the likelihood of CCS developing rapidly enough to meet global standards.

“The industry needs to commit to genuinely helping the world meet its energy needs and climate goals—which means letting go of the illusion that implausibly large amounts of carbon capture are the solution,” said Faith Birol, IEA executive director. Birol made the comment in November 2023, when the IEA released a report called “The Oil and Gas Industry in Net Zero Transitions.”

The report stated the energy industry was not doing enough to cut emissions overall, and current reduction plans would not come close to the targets set by the Net Zero by 2050 goals.

“Carbon capture, currently the linchpin of many firms’ transition strategies, cannot be used to maintain the status quo. If oil and natural gas consumption were to evolve as projected under today’s policy settings, limiting the temperature rise to 1.5 degrees C would require an entirely inconceivable 32 billion tons of carbon captured for utilization or storage by 2050, including 23 billion tons via direct air capture,” Birol said in his statement.

“The amount of electricity needed to power these technologies would be greater than the entire world’s electricity demand today.”

The pipeline projects also face opposition from local opponents.

A third CCS project on the table, Navigator CO2 Ventures’ Heartland Greenway pipeline, died in October after the South Dakota government denied a permit. The project would have had a capacity of 15 MMmt/y of CO2 from Midwest ethanol plants.

The opposition to these projects tends to consist of people typically on opposite ends of the political spectrum—environmentalists and people concerned about land rights.

In Iowa, opposition groups announced in mid-July that they would continue to fight Summit’s plan. The groups include Republican legislatures and the Sierra Club.

“Our allies are our allies,” said state Rep. Charley Thomson, who is part of a group of Iowan Republican legislators who have challenged Summit’s permit application, according to a report in the Iowa Capital Dispatch. “I’m not going to pick a fight with the Sierra Club because we differ on some other issues. We are going to march together.”

Carbonized complications

Another concern for developers is the actual product. Shipping CO2 through pipelines is not as straightforward as shipping natural gas.

CO2 has almost three times the weight of methane, the primary ingredient in natural gas. CO2 also has a much lower freezing point than methane, meaning that the greenhouse gas can turn to ice during pressurization and depressurization activities, said Ashutosh Nischal, a senior director of the low-carbon energy sector at Worley Group.

The technical challenges facing CO2 pipelines are significant, he said during a session at the Carbon Capture Technology Expo in June at the NRG Center in Houston. Companies also face the problem of a lack of experience handling long-haul CO2 pipelines.

“There’s limited experimental data available for the designers, the manufacturers and the operators to use, which obviously stretches the confidence level of the industry,” Nischal said.

One of the biggest problems researchers are currently studying is the reactivity of impurities within the CO2 stream. Any water that is not filtered out of the CO2 will tend to create inorganic acids, including sulfuric acid, he said. Corrosion will therefore tend to be a larger problem on CO2 pipelines, as opposed to natural gas lines, which do not have the same kind of reactivity.

CO2 also causes different problems during pressurization. The high pressures required to move the product essentially do not give midstreamers the option of building the pipe above ground under normal circumstances, he said.

Midstream companies will therefore have to make strong efforts to take into the new technical information for the systems.

“If you’re not aware of it, then obviously you won’t design for it,” he said.

Nevertheless, Nischal said his company sees a strong market developing for CCS networks. The key for those entering the sector will be getting over the learning curve.

“We see a lot of interest by organizations trying to set up a carbon management business that is tapping into the ever-increasing demand of CO2 transport,” he said. “The industry data shows that the pipelines are one of the best-suited and most efficient ways of transporting the CO2. Hence, there’s an urgent need to facilitate pipelines for carbon management.”

Recommended Reading

Appalachia, Haynesville Minerals M&A Heats Up as NatGas Prices Rise

2025-04-03 - Several large Appalachia and Haynesville minerals and royalties packages are expected to hit the market as buyer interest grows for U.S. natural gas.

NOG Spends $67MM on Midland Bolt-On, Ground Game M&A

2025-02-13 - Non-operated specialist Northern Oil & Gas (NOG) is growing in the Midland Basin with a $40 million bolt-on acquisition.

Nabors SPAC, e2Companies $1B Merger to Take On-Site Powergen Public

2025-02-12 - Nabors Industries’ blank check company will merge with e2Companies at a time when oilfield service companies are increasingly seeking on-site power solutions for E&Ps in the oil patch.

Report: Diamondback in Talks to Buy Double Eagle IV for ~$5B

2025-02-14 - Diamondback Energy is reportedly in talks to potentially buy fellow Permian producer Double Eagle IV. A deal could be valued at over $5 billion.

Ring Energy Closes Central Basin Platform M&A from Lime Rock

2025-04-01 - Ring Energy added 17,700 net acres and 2,300 boe/d of production in the Central Basin Platform through an acquisition from Lime Rock Resources IV.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.