The U.S. natural gas market is in the midst of a sea change.

Prices, adjusted for inflation, are as low as they’ve been in the last 30 years. Energy companies, however, continue to spend billions on new infrastructure in the hopes of a massive demand increase expected to hit before the end of the decade.

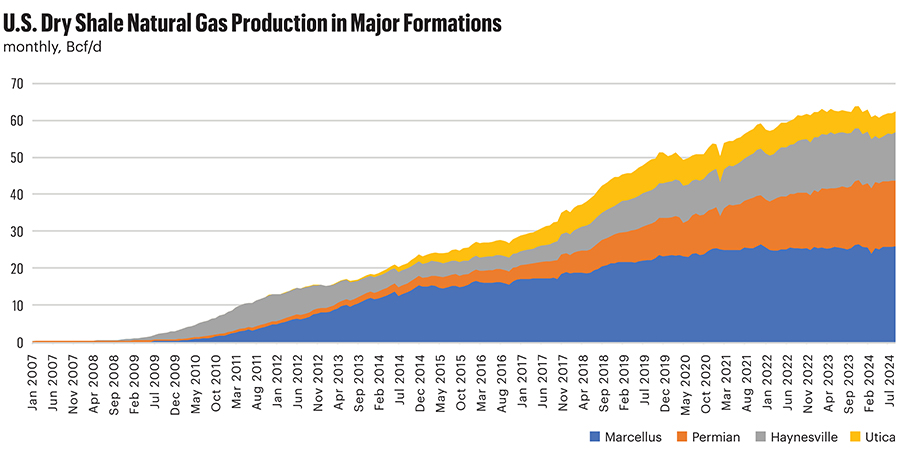

Yet most of that development is happening on the Gulf Coast, via pipelines in Texas and LNG plants in Louisiana. The nation’s largest gas field on the eastern side of the U.S., the Marcellus Shale, has seen little of the transformations shaking the industry along the Gulf Coast.

The Marcellus has steadily produced natural gas for more than a century and has plenty of reserves for a future of increased demand for exports and power generation. While producers continue to develop the region and extol the basin’s low-cost, high-quality virtues, low prices have led to flattened and—in some cases reduced—production.

CEOs are often fighting political battles for permission to build infrastructure. An appeals court recently revoked a permit for a pipeline infrastructure project that was already operational, and the Mountain Valley Pipeline faced never-ending protests and court actions until the government intervened.

“It’s never been more important for us to produce energy in this country—whether it’s increasing LNG exports to protect our allies, addressing the situation in Ukraine or powering the AI boom that’s taking place,” Toby Rice, president and CEO of EQT Corp., told Oil and Gas Investor (OGI). EQT bases its operations primarily in the Marcellus and the Upper Devonian in West Virginia.

Shallow and dry

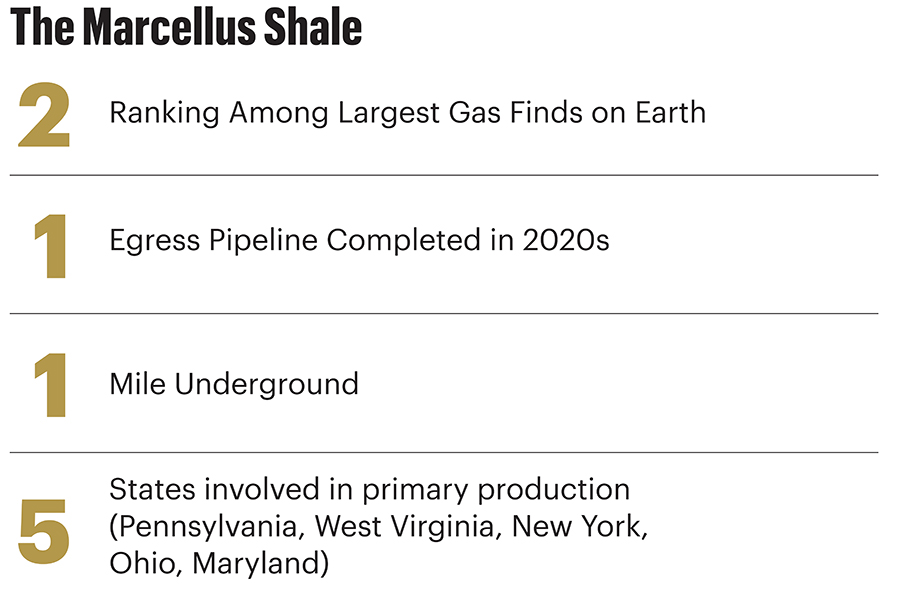

The Middle Devonian Marcellus Shale stretches from the northeast in New York, to the mid-Atlantic in Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Maryland, and to the Midwest in Ohio.

The formation is generally about a mile beneath the surface and about 1,000 feet above the Utica Shale. Due to the different depths, the two basins provide different products.

The Utica is a major producer of oil and NGL. The Marcellus provides mostly dry gas, meaning it’s composed primarily of methane and requires little processing before being shipped to market. API describes it as the second-largest natural gas find on Earth.

There are advantages and disadvantages to the Marcellus’ makeup. As of a result of its shallower depth, it’s cheaper to drill into the Marcellus than the Utica. Dry gas also costs less to commercialize because of lower processing fees.

However, NGL can be a useful buffer for producers when natural gas prices dip. The NGL composite price held steady for much of the first half of the year at $6.91/MMbtu, while the cost of natural gas had fallen by about one-third, the Energy Information Administration said.

The Marcellus does produce some NGL, but natural gas is the primary product by far. Pennsylvania led the basin in gas production, producing 85% of the region’s output in 2024, according to Rextag.

At the end of 2023, the region had almost 40 rigs in operation. That figure declined to around 25 by the middle of the summer, according to East Daley Analytics, as low prices forced production cuts.

“What’s happening in the U.S. over the last 15 years is that demand has grown 50% for natural gas but natural gas infrastructure has only grown 25%,” Rice said in a separate interview with NPR. “Most importantly, natural gas storage infrastructure has only grown 12%. That means that we haven’t built up enough pipelines to keep up with demand and the infrastructure is maxed out. We need more infrastructure built in America and, if you have the opportunity, build it in Appalachia.”

Appalachia, known for its coal production, has usually trailed in the development of its petroleum resources. The Marcellus, however, did play a pioneering role in the shale gas revolution.

The Yom Kippur War connection

The discovery and eventual exploitation of the Marcellus was triggered by the Yom Kippur War in 1973.

U.S. support for Israel led to an oil embargo by Arab members of OPEC, which caused a panic on the international market. The price of a barrel of crude in the U.S. doubled and then quadrupled, eventually leading to long lines and short supplies at the country’s gasoline stations.

President Richard Nixon declared the need for energy independence and began several programs aiming to boost domestic energy supplies. President Jimmy Carter placed those programs under the umbrella of the newly formed Department of Energy (DOE) in 1977.

One of the first projects brought under the DOE’s purview was the Eastern Gas Shales Program, which focused on developing gas fields that had been marginal or unreachable.

Appalachian gas deposits were known since the late 1800s, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior. The department estimates that the first natural gas companies had already extracted 3 Tcf by the end of the 1970s from the area’s shallow deposits.

The Eastern Gas Shales Program, run by the DOE’s Bureau of Mines, focused on the Dunkirk and Huron shales in Ohio, said Terry Engelder, who took part in the DOE research as a professor of geosciences at Penn State University.

“The Marcellus was actually an afterthought in terms of sampling, and there were only three or four wells of those 32 (in the program) that penetrated the Marcellus off of that program,” Engelder said.

Engelder would play a large role in the eventual development of the Marcellus, and he’s currently writing a book about the basin’s history, with the working title, “Breaking Rocks.”

Engelder grew up in Wellsville, New York, a small town in the western part of the state, close to the Pennsylvania border. He had an early interest in geology and once won a high school science fair with his project on geological faulting near his home town.

As an academic, Engelder studied the Marcellus with the sponsorship of a DOE grant in 1978. The formation is geologically interesting, and Engelder found evidence that a wealth of gas in the formation was pushing upward, causing vertical cracks in the horizontal layers noticeable through cuts made by rivers.

Nothing immediately happened in the Marcellus after the studies, and the Eastern Gas Shales Program ended in 1992.

The program’s research, however, aided Barnett Shale pioneer George Mitchell and his team in Texas in their project to build the world’s first successful unconventional shale play.

As Mitchell’s success opened up new plays, attention focused back on the Marcellus and the earlier studies that had shown the potential for development.

By 2004, Range Resources, convinced by company geologist Bill Zagorski, decided to “put a massive frack on the Marcellus,” Engelder said. “They started leasing land like mad in southeastern Pennsylvania—Washington County mainly.”

Chesapeake Energy (now Expand Energy) followed with a major move in the area. In 2007, Engelder, now a full-time academic at Penn State, was asked after a lecture just how big the potential natural gas reserves were in the area. His initial calculations, using the latest geologic data, showed a potential for more than 40 Tcf.

After Penn State published the data, accompanied by some of Range Resources production numbers, lease rates in the area jumped from under $100 an acre to as much $5,000.

Slow build

That initial boom has slowed, as compared to the continued rapid development of the Permian Basin in Texas and New Mexico. However, infrastructure companies have seen their deliveries increasing.

“Over the past five years we have grown volumes significantly, and increased margins without any large-scale acquisitions, but instead through expansion projects,” said Williams Cos.’ Larry Larsen, senior vice president of gathering and processing.

The recent focus in the Marcellus has been on infrastructure projects needed to take the natural gas to market. Williams, the largest gas gatherer in the Appalachians, has spent the latter part of 2024 battling in the courts to continue operating a project that was already completed.

In July, the Court of Appeals for the D.C. District vacated the Federal Energy Reserve Commission’s (FERC) permits for the Regional Energy Access (REA) project, which delivers natural gas to utilities in the mid-Atlantic. The move came after the company had completed the project.

The REA is a $950 million expansion that adds about 829,000 dekatherms of energy capacity to an existing pipeline system.

The appeals court ruled that the market need for the gas had not been sufficiently proved to FERC. The company filed for a temporary permit to continue operations until the courts and FERC could work through the problem.

“The United States has a vast natural gas resource in the Marcellus, but supplies are constrained due to lack of infrastructure. Costly pipeline project delays occur due to duplicative permitting processes, a lack of cooperation among regulatory agencies, and inadequate judicial review standards,” Larsen told OGI.

“In fact, between 2013 and 2022, natural gas demand has grown by 43%, with only 25% growth in infrastructure to handle it. We can, and should, modernize the federal permitting process to benefit all energy sources, not just natural gas. Specifically, we are calling on Congress to restore the balance intended in the Natural Gas Act by removing the one-state veto power loophole in the current law.”

Williams plans to continue expanding in the Northeast and delivering gas to other markets. The Transco Southeast Supply Enhancement project will distribute supplies from the newly operational Mountain Valley Pipeline to the southeastern United States. Once approved by FERC, the system will add about 1.6 Bcf/d of natural gas capacity to Williams’ Transco system in 2027.

Old and hale

Engelder said he was hopeful about production in the Marcellus. Some of the first wells drilled in the region continue to provide strong output for producers.

“It’s very difficult to say when you talk about the foreseeable future, but we know that gas wells last up to 40 years,” he said. “My suspicion is that a well that is drilled in 2020—it is pretty easy to imagine that that well will still be going in the year 2060.”

He said the key for producers was to keep active, as the market for gas in the region will eventually catch up to other parts of the U.S.

“I’m optimistic that these gas wells will just really keep going,” he said. “Like the Energizer Bunny.”

Recommended Reading

Buying Time: Continuation Funds Easing Private Equity Exits

2025-01-31 - An emerging option to extend portfolio company deadlines is gaining momentum, eclipsing go-public strategies or M&A.

Phillips 66’s Brouhaha with Activist Investor Elliott Gets Testy

2025-03-05 - Mark E. Lashier, Phillips 66 chairman and CEO, said Elliott Investment Management’s proposals have devolved into a “series of attacks” after the firm proposed seven candidates for the company’s board of directors.

EON Deal Adds Permian Interests, Restructures Balance Sheet

2025-02-11 - EON Resources Inc. will acquire Permian overriding royalty interests in a cash-and-equity deal with Pogo Royalty LLC, which has agreed to reduce certain liabilities and obligations owed to it by EON.

Not Sweating DeepSeek: Exxon, Chevron Plow Ahead on Data Center Power

2025-02-02 - The launch of the energy-efficient DeepSeek chatbot roiled tech and power markets in late January. But supermajors Exxon Mobil and Chevron continue to field intense demand for data-center power supply, driven by AI technology customers.

Chevron to Lay Off 15% to 20% of Global Workforce

2025-02-12 - At the end of 2023, Chevron employed 40,212 people across its operations. A layoff of 20% of total employees would be about 8,000 people.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.