What if it rains?

No, not “what’s Plan B for the Father’s Day picnic?” What if it really rains, like a Category 4 or 5 hurricane in the Gulf of Mexico with the force to tear apart infrastructure and cripple an economy?

The answer is a big fat “it depends.”

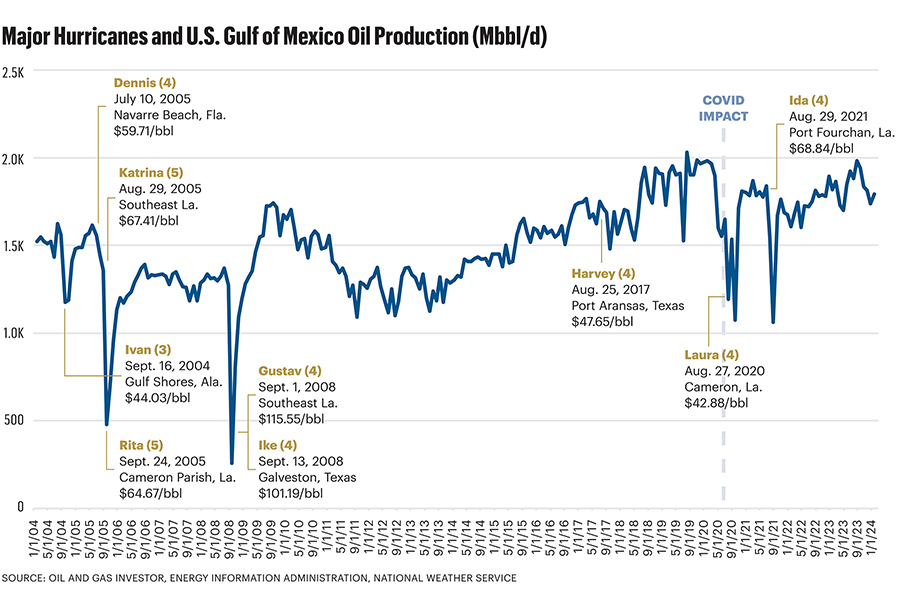

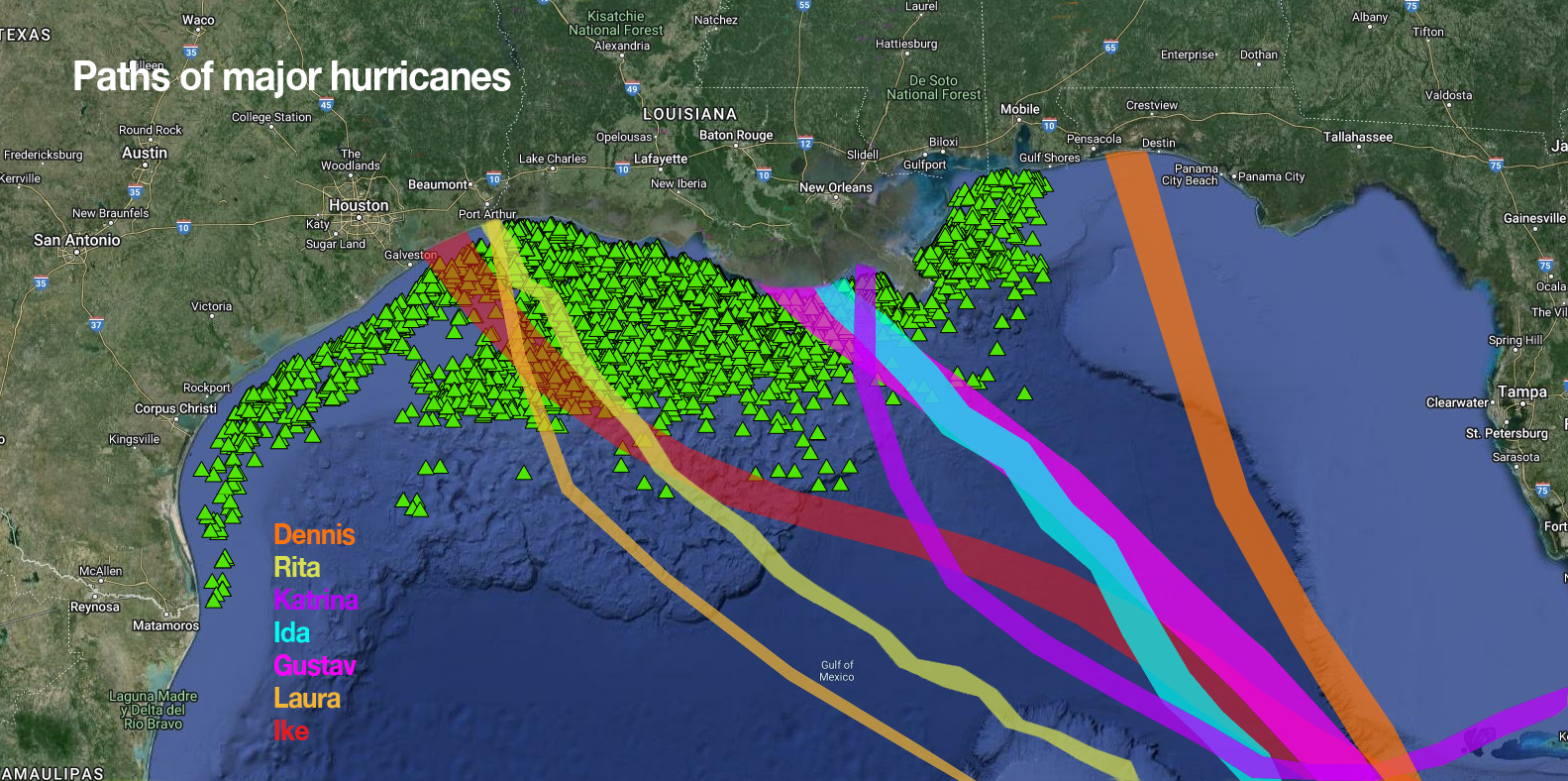

From July 2025 through September 2005, three major hurricanes tore through the Gulf. The first was Dennis in July. Katrina in August and Rita in September collided with more than 3,000 platforms and 22,000 miles of pipelines in their direct paths.

Katrina entered the outer continental shelf as a Category 5 and destroyed 46 platforms, damaging 20 others, the Minerals Management Service said in its 2006 assessment. Rita, a Category 4 when it entered the area, knocked out 69 platforms and damaged 32 others.

Prior to those three storms, Gulf of Mexico oil production averaged 1.56 MMbbl/d in June. Production would not reach that level again until July 2009.

Many of those offshore facilities were older and not as equipped for powerful storms as they are now. Still, in July 2021, Gulf oil production was 1.85 MMbbl/d. Hurricane Ida struck in August and production would not recover until January 2023.

But those figures are restricted to the U.S. Gulf of Mexico. Overall U.S. production dipped temporarily but shale fields were able to compensate. Oil prices barely sustained a scratch.

Busy season ahead?

In 2023, the U.S. produced more crude oil than any other country in the world. More than one of every seven of those barrels was produced in the offshore Gulf of Mexico.

Offshore production is expected to grow, with the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management forecasting output to peak at an average of 2.06 MMbbl/d in 2027 (compared to an average of 1.8 MMbbl/d in February).

But again, what if it rains?

Researchers at Colorado State University predict 23 named storms for the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season, well above the average of 14.4. Of those, 11 are expected to be hurricanes, with five major hurricanes. There were 19 named storms in 2023, with four coming onshore: Hurricane Idalia, and Tropical Storms Harold, Lee and Ophelia.

The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts predicts 23 named storms for 2024, as well. AccuWeather forecasts 20-25 named storms, eight to 12 of which are hurricanes, with four to seven major hurricanes and four to six direct U.S. impacts. A team at the University of Pennsylvania forecasts an unprecedented 33 named storms.

Before dismissing these forecasts as climate change hokum designed to goose electric vehicle sales, remember that the “Great Storm” that devastated Galveston, Texas in 1900—the deadliest weather event in U.S. history—was what is now defined as a Category 4 hurricane.

It struck eight years before Ford’s first Model T rolled off the assembly line, so auto emissions were not a factor. It also happened to be a year of very high-water temperatures.

Like this year.

In hot water

“This year’s sea surface temperatures in the eastern and central tropical Atlantic are much warmer than normal, also favoring an active Atlantic hurricane season via dynamic and thermodynamic conditions that are conducive to developing hurricanes,” the Colorado State researchers wrote.

They compared this year’s January-March sea surface temperatures to other years with the same conditions. In 1926, there were only 11 named storms, but eight were hurricanes and six were major hurricanes. In 2020, there were 30 named storms, 14 of which were hurricanes, with seven major hurricanes.

Hurricanes enter coastal lore based on relative levels of destruction. When storms begin to touch land, they start to lose energy. Rarely does a storm come ashore above Category 3, with exceptions of monsters like Camille, Andrew and Hugo. By contrast, there is no easing in the outer continental shelf. A Category 4 or 5 hurricane will smack a platform with everything it’s got.

The advantage is in people affected. Casualties are rare on offshore facilities because they are evacuated well before a storm can wreak havoc. There are no odd characters determined to ride it out at sea.

So, again, what if it rains?

Those of us who have lived on the Gulf Coast for a while have vivid memories of Allison, Ike, Katrina, Harvey and other storms. My neighborhood in Houston is far better prepared for flooding after improvements to the nearby bayou following Harvey’s deluge. Out in the Gulf, platforms are now able to withstand waves higher than Katrina’s 82 feet and winds up to 144 mph.

Past hurricane performance is not a guarantee of future gales, of course, but given how the offshore oil industry specifically and the Gulf Coast in general have been clobbered previously, it’s best to be prepared. And we are prepared as we can be … for the last storm, at least.

Recommended Reading

E&P Highlights: June 17, 2024

2024-06-17 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including Woodside’s Sangomar project reaching first oil and TotalEnergies divesting from Brunei.

Beetaloo Juice: US Shale Explores Down Under

2024-06-28 - Tamboran Resources has put together the largest shale-gas leasehold in Australia’s Beetaloo Basin, with plans for a 1.5+ Bcf/d play. Behind its move now to manufacturing mode are American geologists and E&P-builders, a longtime Australian wildcatter, a U.S. shale-rig operator and a U.S. shale pressure-pumper.

Deepwater Roundup 2024: Americas

2024-04-23 - The final part of Hart Energy E&P’s Deepwater Roundup focuses on projects coming online in the Americas from 2023 until the end of the decade.

Empire Petroleum’s Williston Drilling Program Identifies New Zones

2024-05-16 - Empire Petroleum provided updates on its Williston Basin development drilling program in its first quarter 2024 earnings results.

Trio Petroleum to Increase Monterey County Oil Production

2024-04-15 - Trio Petroleum’s HH-1 well in McCool Ranch and the HV-3A well in the Presidents Field collectively produce about 75 bbl/d.