SRI’s proprietary CoEx printing technology was used at a pilot scale for printing silver gridlines on solar panels (photo is that printer set-up). (Source: SRI International)

An energy project affiliated with the University of Houston (UH) that could solve three problems at once has received funding from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

Reducing emissions, improving the efficiency of renewable power, and cutting the cost of liquid fuel are problems the project tackles.

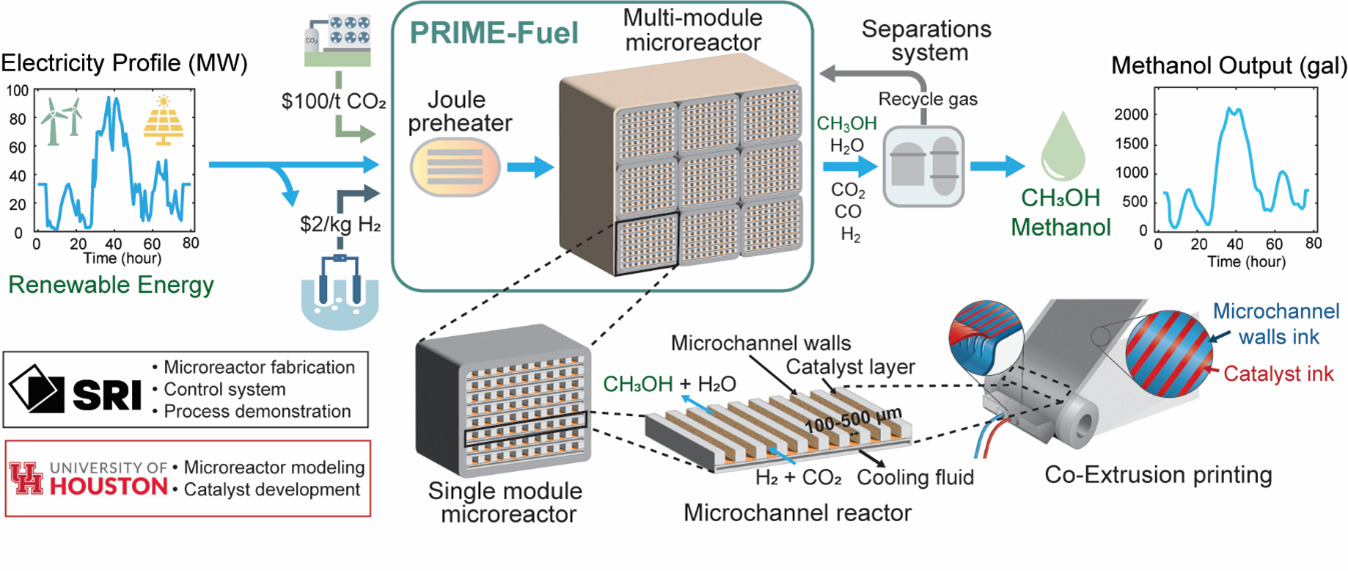

The proposed solution? A modular microreactor that uses variable supplies of renewable energy to convert CO2 into methanol.

The DOE announced the $3.6 million grant in November to a group led by the nonprofit research institute SRI International and UH. The award is part of $41 million in funding toward developing technologies that use renewable power to produce low-carbon liquid fuels.

“We can help combat climate change while providing valuable resources for various industries by leading to cost-effective and sustainable methanol production,” said Rahul Pandey, a UH graduate who is now a senior scientist at SRI and principal investigator on the project. UH faculty members Vemuri Balakotaiah and Praveen Bollini are co-investigators.

Methanol can serve as a versatile energy carrier and high-energy density liquid fuel, potentially replacing fossil fuels in various applications, according to SRI. It is also a valuable chemical feedstock that is easily stored and transported.

Converting CO2 into methanol (CH3OH) requires high pressure and temperature that typically call for a grid-connected power source, Pandey told Hart Energy. That source would generate both costs and emissions.

The output of the SRI microreactor would rise and fall based on power availability. The reactor would run hard to take advantage of cheap renewable power when wind and solar come online in times of low demand, then dial back as higher demand pushed up prices. The reactor could run even when the renewable energy supply dipped to 5% capacity.

“Because of the nature of this renewable energy, we cannot rely on the energy directly coming into the plant,” Pandey said. “We have to come up with a design which can adapt itself as these feeds are changing and still continue to produce methanol.”

In this project, the researchers will develop a prototype that can produce 30 megajoules per day of methanol. Associated emissions would drop by almost 90%.

Also, Pandey said, the technology has wider applications.

“Right now, we are aiming to produce methanol,” he said. “But this technology can actually be applied to a much broader set of energy carriers and chemicals.”

Recommended Reading

PrePad Tosses Spreadsheets for Drilling Completions Simulation Models

2025-02-18 - Startup PrePad’s discrete-event simulation model condenses the dozens of variables in a drilling operation to optimize the economics of drilling and completions. Big names such as Devon Energy, Chevron Technology Ventures and Coterra Energy have taken notice.

Digital Twins ‘Fad’ Takes on New Life as Tool to Advance Long-Term Goals

2025-02-13 - As top E&P players such as BP, Chevron and Shell adopt the use of digital twins, the technology has gone from what engineers thought of as a ‘fad’ to a useful tool to solve business problems and hit long-term goals.

Aris CEO Brock Foresees Consolidation as Need for Water Management Grows

2025-02-14 - As E&Ps get more efficient and operators drill longer laterals, the sheer amount of produced water continues to grow. Aris Water Solutions CEO Amanda Brock says consolidation is likely to handle the needed infrastructure expansions.

How DeepSeek Made Jevons Trend Again

2025-03-25 - As tech and energy investors began scrambling to revise stock valuations after the news broke, Microsoft Corp.’s CEO called it before markets open: “Jevons paradox strikes again!”

Halliburton, Sekal Partner on World’s First Automated On-Bottom Drilling System

2025-02-26 - Halliburton Co. and Sekal AS delivered the well for Equinor on the Norwegian Continental Shelf.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.