The importance of Apache’s infrastructure, such as its NGL loading facility, is easily lost in the vastness of the Permian Basin and its army of operators. E&Ps face the challenges not just of transporting hydrocarbons out of the basin but also opening investors’ eyes to the value of their infrastructure. (Source: Apache Corp.)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the October 2018 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

Not long after Brazos Midstream Holdings LLC was formed, the young company in need of a deal found a southern Delaware operator with an inwardly focused gathering system.

Jetta’s infrastructure was “what I’d call a starter kit,” Brazos chief commercial officer Stephen Luskey said.

The assets included a tank battery connected to about half of Jetta Operating Co. Inc.’s shallow crude oil wells. Brazos built out Jetta’s operations, looping the main trunk line with steel, and expanded Jetta’s production with steel high-pressure lines—all with the vision of building a grander system to connect with third parties and future growth.

“In essence, we biggie sized it,” Luskey said. And Brazos continued to do so, year after year. In May, the company was part of the recent wave of midstream M&A largely crashing down on the Permian Basin. Brazos and private-equity backer Old Ironsides Energy LLC sold the company to an investment fund run by Morgan Stanley for $1.75 billion.

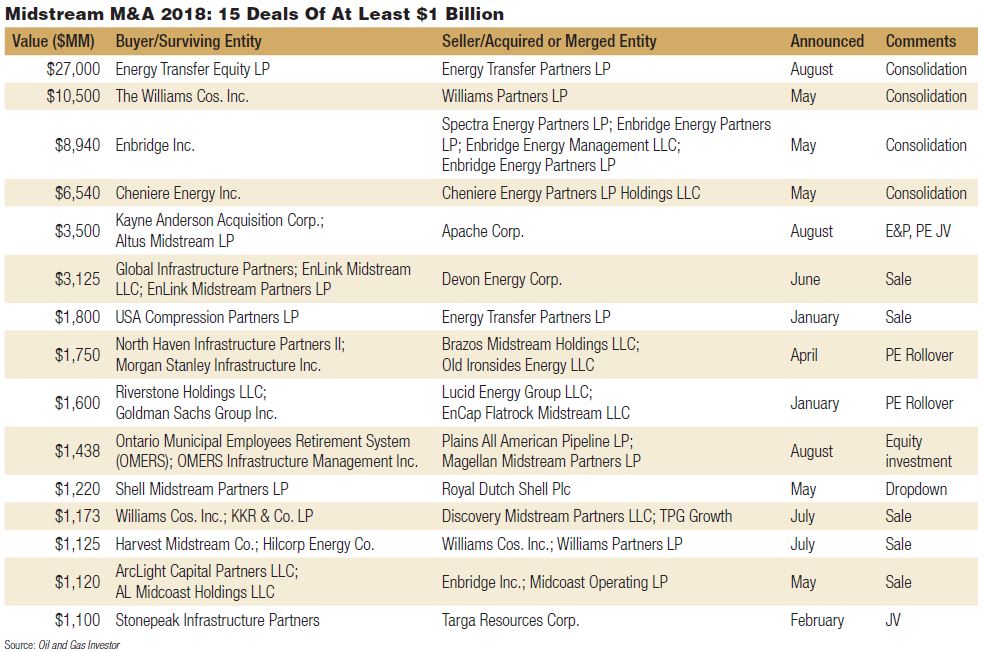

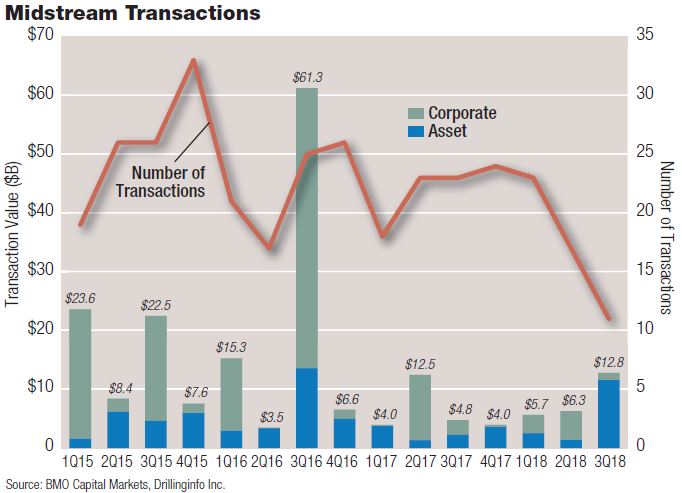

Brazos was part of the second quarter’s $35.15-billion deal flow, which PwC called “a record high second quarter” for the midstream sector. A year ago, the second-quarter produced 13 midstream deals valued at $9.4 billion, according to PwC. Those deals have in general fallen into the categories of outright purchases; companies streamlining their structures; and private-equity rollovers.

The transactions aren’t much of a surprise for Brazos executives, who can rattle off E&P deals by year.

“We’ve been living it real time for the last three and a half years,” William Butler, Brazos’ CFO, told Oil and Gas Investor.

“What I think is interesting … is that there’s sort of a new tier of buyer in the last two or three years that has really developed in the midstream space out here in the Permian,” he said. “The larger private-equity shops that, as you’ve seen … take these assets on and continue to grow them.”

“What we saw in the second quarter falls into three transaction types,” said Joe Dunleavy, PwC U.S. deals leader. “MLP to C-corp conversions … traditional MLP dropdowns and basic M&A transactions.”

Dunleavy said activity is likely to continue, particularly in areas such as the Permian where production continues to grow.

“As production goes up, they’re going to have to move it,” he said. “And they’re going to move it to the midstream.”

Deals in the sector will continue as a matter of practicality.

“When you look at where we are in this country from an infrastructure perspective, there are only so many midstream assets,” he said. “And that scarcity makes them valuable.”

Combo Deals

Beyond the recent gaudy numbers, however, about 62% of the quarter’s deal value was tied to MLPs converting to C-corps or otherwise streamlining their structures. Since June, billions of dollars have continued to be tied to midstream deals that are largely companies buying their subsidiaries.

Companies with MLP subsidiaries have justified the moves, variously, as ways to tear down unnecessarily complex structures, eliminate costly incentive distribution rights (IDRs) to unitholders or to avoid tax liabilities that could affect MLPs.

In June, Tallgrass Energy Partners LP and Tallgrass Energy GP LP merged in a stock-for-unit transaction PwC valued at $3.14 million. A newly combined C-corp, Tallgrass Energy LP (NYSE: TEP), later said the transaction eliminated its “IDR burden” and “reduced complexity.”

Other MLPs rolled up assets over fears that an income tax policy, reversed by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in March, would penalize MLPs with interstate oil and natural gas lines.

RELATED: EnLink Continues Wave Of Midstream Consolidation

Citing those concerns, on Aug. 10, The Williams Cos. Inc. (NYSE: WMB) completed the acquisition of its MLP subsidiary, Williams Partners LP, for a stock-for-unit deal worth an estimated $15.9 billion. Canada’s Enbridge Inc. (NYSE: ENB) similarly rolled up four U.S. subsidiaries and converted to a corporation over tax worries in an $8.9-billion stock-unit transaction.

Energy Transfer Equity (ETE) was among the most recent to dismantle its MLP subsidiary. In August, ETE acquired Energy Transfer Partners, with a market cap of $22.2 billion, for ETE shares worth roughly $26.8 billion. As part of the agreement, ETE jettisoned its IDRs, which the company said would “reduce the cost of equity for the combined entity.”

Private-equity firms have also faced less competition as natural aggregators have dealt with the noise of reorganizations. Investors’ lingering distrust in commodity prices has also put MLPs in front of a public-equity market largely disinterested in them.

“They’ve had, I think, capital constraints,” said William R. Lemmons, managing partner and founder of Flatrock. “The more traditionally aggressive players in our business are not able to compete as aggressively as they have in the past, and so it’s opened up opportunities for us.”

Outside of such transactions, straightforward asset deals have largely been the domain of private-equity firms.

The Big Rollover

In the outwash plains of Reeves County, Texas, the prized southern Delaware Basin resides beneath a flat, sandy, no man’s land where less than a foot of rainfall trickles down each year.

Brazos Midstream’s management came to the area in 2015 with no assets, backing from Old Ironsides and the need for a deal.

Luskey described the team as “basically four guys in a truck.”

But the truck was fully loaded with expertise learned at EnLink Midstream LLC, Athlon Energy Inc., Wildcat Midstream Partners LLC and XTO Energy Inc.

Jetta’s operations in Ward and Reeves counties “really gave us a foothold in the Delaware Basin,” Butler said.

During the height of the A&D spree, Brazos worked with some of the largest companies and acquirers in the Permian—Parsley Energy Inc. (NYSE: PE), Diamondback Energy Inc. (NASDAQ: FANG), Concho Resources Inc. (NYSE: CXO) and Callon Petroleum Co. (NYSE: CPE)—giving the company a material platform in the emerging basin from the middle of 2015 through 2017.

“You saw the A&D explosion on the upstream side, and we were basically going along very methodically to make sure we were being aggressive, but not taking unnecessary, speculative risks.”

Within three years, Brazos executives began considering a sale. By then, the company had built out a 300-mile natural gas gathering pipeline and another 50 miles for crude—a distance exceeding all of the state, interstate and U.S. highways in Reeves and Ward, combined.

Brazos’ buyer: another private-equity fund, North Haven Infrastructure Partners II, which is managed by Morgan Stanley.

Over the course of the year, as Permian M&A activity has varied from one-off strategic transactions to auctions, private equity has often stepped in with offers of what Wesley P. Williams, a corporate and securities attorney at Thompson & Knight, calls “rollovers.”

In a rollover, a larger private-equity firm buys the assets of another firm.

“We’ve seen strategic buyers in the data rooms making bids,” Williams said. “But I think there’s been so much money raised by the private-equity funds over the course of the last 10 years and plenty of it to put to work that it makes them pretty formidable in a bid process.”

Some private-equity firms also play both sides.

Last year, EagleClaw Midstream Ventures LLC—backed by private-equity firm EnCap Flatrock Midstream—sold its southern Delaware Basin midstream asset for $2 billion. The buyer: private-equity funds Blackstone Energy Partners and Blackstone Capital Partners.

William R. Lemmons, a managing partner and founder of Flatrock, said private-equity’s investment role in midstream companies, and E&Ps, is becoming more visible as firms continue to generate headline transactions.

“Capital market challenges have had the strategics somewhat sidelined for a couple of years A number of private buyers are stepping into the opportunity and successfully acquiring some really great businesses,” said Lemmons.

The makeup of active buyers has changed in the past couple of years, Lemmons said.

“We’ve seen a lot more financial players show up,” he said. “They’ve always been in the processes, but in recent years they’ve been the ones to transact and close deals with the largest and most respected players in our industry.”

Matchmaking

Black Diamond Gathering LLC’s 160-mile pipeline system crisscrosses Weld County, Colo., fording the South Platte River—a scenic haven for fly fishing—in at least four places.

Black Diamond emerged as a marquee midstream name in the heart of the Denver-Julesburg (D-J) Basin, despite its recent born-on-date: Jan. 31. The company was built around a $638.5 million cash purchase of Saddle Butte Rockies Midstream LLC by Noble Midstream Partners LP (NYSE: NBLX) and Flatrock-backed Greenfield Midstream LLC.

The companies created Black Diamond through a JV, which Noble will operate while Greenfield works to grow its commercial success.

In addition to its 300,000 bbl/d of oil capacity, Black Diamond offers the D-J Basin the only midstream service provider able to deliver to all major long-haul crude outlets through connections to the White Cliffs, Saddlehorn, Grand Mesa and Pony Express pipelines.

Roughly eight months later, Flatrock-backed Lotus Midstream LLC agreed to acquire Occidental Petroleum Corp.’s (NYSE: OXY) 3,000-mile Centurion pipeline system and a Southeast New Mexico oil gathering system. Separately, Flatrock-sponsored Moda Midstream LLC entered a deal to purchase Oxy’s Ingleside storage and export terminal. Together, the deals totaled $2.6 billion.

Flatrock and other companies have been keen to put money to work in similar deals for years. But Flatrock’s investments have a clear end in mind: “We are going to exit at some point in time. We are not a permanent form of capital,” Lemmons said.

Every player on the private side has their own model of investing, and that includes how they look at exits, he said.

“Some want to acquire or develop from the ground up, expand and sell. Others operate around building sufficient critical mass for an IPO,” he said. “Both models can be successful. We try to be open-minded around the goals of our management teams, but to date, all of our exits have been a cash sale, and I think that will always be our preferred path to liquidity.”

Its recent deals with Oxy will be no different, Lemmons said.

For Oxy, the deal unburdens any interference with its upstream focus. In a conference call, Oxy executives noted that the portion of its midstream assets wasn’t integral to operations, and the company would retain its long-term flow assurance, pipeline takeaway and most of its export capacity.

“I think that it is a good example of really a top-tier producer seeing the opportunity to do some other things,” Lemmons said.

Other E&Ps are eager to gain value from their midstream assets, but not merely by selling them off.

Isolation

What’s striking to some observers is the way strategic players and E&Ps have banded together to solve takeaway capacity in the Permian without resorting to building infrastructure from the ground up.

In early August, ExxonMobil Corp. (NYSE: XOM) was the latest operator to sign a letter of intent for the Permian Highway Pipeline Project, committing production generated by subsidiary XTO Energy.

The $2 billion project will move 2 billion cubic feet per day of natural gas along a 430-mile, 42-inch line from Waha to Katy, Texas. The project involves Kinder Morgan Inc. (NYSE: KMI), EagleClaw Midstream Ventures LLC and Apache Corp. (NYSE: APA). On the crude oil side, EPIC Midstream Holdings LP’s pipeline has picked up commitments from Apache, Noble Energy Inc. and a strategic partner in Diamondback Energy.

For some E&Ps, the dilemma they face is the value of their midstream assets becoming obscured by their upstream success. In August, Diamondback subsidiary Rattler Midstream Partners LP filed regulatory documents for an IPO of its 528-mile network of crude, natural gas and water pipelines.

Companies are “trying to isolate the value of a midstream asset embedded with an E&P company,” Kevin McCarthy, chairman of the Kayne Anderson Acquisition Corp. (KAAC) board of directors, told Investor.

To draw out that value, some E&Ps are also entering JVs—exchanging some control and interest for expertise in building out a pipeline.

In April 2017, McCarthy led KAAC, a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC), in an attempt to find a nearly idealistic deal: a moneymaker with no debt. Roughly 16 months after KAAC formed, Apache said in August it would form a $3.5-billion midstream company with KAAC called Altus Midstream LP.

McCarthy said KAAC was formed after it became clear an imbalance of midstream buyers and sellers was developing.

McCarthy has long supported IDRs and the MLP structure, but “clearly IDRs have a life cycle and they’re not well received in the market right now,” he said. “A lot of institutional investors can’t and won’t invest in MLPs, and IDR simplifications have been one of the major trends in the midstream space over the last 18 months. So we wanted to appeal to as broad an investor space as possible.”

The company instead pitched a conventional corporate structure with little to no leverage that would be self-financing. The seller would need to be willing to forgo debt, as well.

“What we were trying to do in the SPAC was create a new way for investors to participate in high-quality and high-growth midstream assets,” he said.

After an upsized IPO, KAAC began to scour transactions—“an awful lot of transactions,” McCarthy said. The company analyzed almost every one of the large midstream deals printed within the past 15 months.

“What we found in Apache is a perfect match between our objectives, starting with little to no leverage and a sponsor that is willing to take back some paper because they saw a significant appreciation going forward,” he said.

Apache had two objectives: offload its midstream capex from the E&P’s balance sheet and unlock the tremendous value of the Alpine High assets while retaining as much ownership of the business as possible.

“From a structure standpoint, it was a meeting of the minds, our structure and what we were looking fit well with what Apache was looking to accomplish,” he said.

Apache also wants a separate spotlight on its assets. The company has secured valuable options for equity participation on five planned pipelines offering connectivity from the Permian to the Texas Gulf Coast.

“We think that those [options] are very attractive, which really transforms the company from what some could see as a captive gathering system to a fully integrated midstream service provider,” he said. “Those are all high-quality pipelines with really good partners, and Apache was able to negotiate those options because of its large presence in the Permian Basin.”

As part of its deal with Apache, KAAC will contribute up to $952 million in cash, comprised of $380 million in proceeds raised in its IPO and $572 million in proceeds raised in a private placement.

Altus will start business with no debt at closing and cash-on-hand to fund ongoing investments.

Stock

Toward the end of August, the midstream deals kept coming.

Plains All American Pipeline LP (NYSE: PAA), Magellan Midstream Partners LP (NYSE: MMP) and OMERS entered into an agreement in which the trio of companies will sell a collective 50% interest in the crude oil BridgeTex Pipeline Co. LLC for $1.44 billion.

And competition remains stiff, including outside of the Permian. Discovery Midstream Partners, which operated oil and natural gas gathering in the D-J Basin, was purchased last July. Almost exactly a year later, Williams and KKR & Co. LP said they would form a joint venture to buy Discovery from TPG Growth for $1.2 billion.

As the pool of potential buyers dries up, McCarthy wonders how much more M&A is left in the sector. He sees the pace of deals generally slowing during the next 12 to 18 months.

“We’ve already seen the majority of transactions that we had anticipated 18 months ago occur,” he said. “The question is how many buyers out there remain? Because there’s only so many dedicated energy private-equity firms that are big enough to acquire these businesses.”

Luskey said companies such as Brazos are equally rare and, at some point, the inventory will run out. “There’s only a handful of guys that you could actually buy,” Luskey said. “And to the extent that you miss that acquisition, it’s virtually impossible to get into the basin.”

Williams said midstream M&A will likely continue through the remainder of the year. But he suspects deal activity will hit a more rapid pace in 2019 and 2020. The reason: greenfield pipeline projects, staked by large capital investments.

“We’ve got a lot of midstream teams that are doing a lot of hard work on building the infrastructure out,” he said.

As if on cue, Flatrock announced Aug. 21 a $200-million commitment to back Candor Midstream LLC, which will hunt for greenfield projects.

Darren Barbee can be reached at dbarbee@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

ADNOC Contracts Flowserve to Supply Tech for CCS, EOR Project

2025-01-14 - Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. has contracted Flowserve Corp. for the supply of dry gas seal systems for EOR and a carbon capture project at its Habshan facility in the Middle East.

Enchanted Rock’s Microgrids Pull Double Duty with Both Backup, Grid Support

2025-02-21 - Enchanted Rock’s natural gas-fired generators can start up with just a few seconds of notice to easily provide support for a stressed ERCOT grid.

McDermott Completes Project for Shell Offshore in Gulf of Mexico

2025-03-05 - McDermott installed about 40 miles of pipelines and connections to Shell’s Whale platform.

DNO Makes Another Norwegian North Sea Discovery

2024-12-17 - DNO ASA estimated gross recoverable resources in the range of 2 million to 13 million barrels of oil equivalent at its discovery on the Ringand prospect in the North Sea.

Baker Hughes: US Drillers Keep Oil, NatGas Rigs Unchanged for Second Week

2024-12-20 - U.S. energy firms this week kept the number of oil and natural gas rigs unchanged for the second week in a row.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.