A dispatch from Dacoma, Oklahoma, Monday, February 28, 2:41 p.m.: “Avard 1H-31. 24-hr oil production, 922 bbls. It came online at midnight on Feb. 26. While cleaning up, it made 298 bbls in the first 12 hrs. In the following 24 hrs, it made 922 bbls. We have only had it into the sales meter since 10 a.m. this morning. It came on spotting 0.8 MMcf to 1 MMcf through a partially plugged, 128/128 choke. Since the obstruction has been cleared, we have seen spot rates up to 4.5 MMcf…Worth sending an update to all of the folks looking at the property. This well is three-quarters of a mile east of the Edwards 1H-36. I don’t think we are seeing any drainage.”

This news was sent to Eagle Energy of Oklahoma LLC headquarters in Tulsa by Ladd Sullins, Eagle operations manager.

It’s Big Oil again in northern Oklahoma and southern Kansas—something the region hasn’t seen since the 1917 discovery of Burbank Field. That shallow-depth monster has produced 317 million barrels to date and launched Phillips Petroleum Corp. It was also pivotal to the growth of Conoco Inc.

The sweetest spot of all? How about under-$2.5-million well costs? Low reservoir risk, scalability and repeatability? Ready rigs? Low-cost proppant? Low-pressure fracs? Take-away infrastructure at the ready? $90 oil?

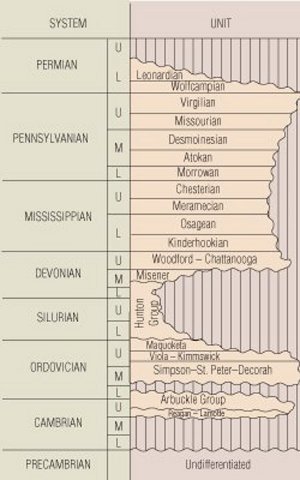

This newest U.S. oil play is horizontal production from the Mississippian-age Chester, Manning, Meramec and Osage mix of limestone, weathered chert or chat, and dolomite. It sits just under the long-drilled Pennsylvanian-age Atoka and Morrow and above the well-known Devonian-age Woodford and Silurian- age Hunton.

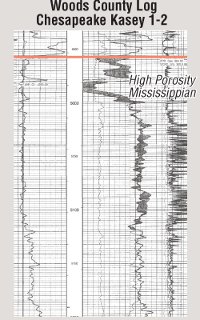

In the western area of the play—in Woods and Alfalfa counties, Oklahoma, and Barber County, Kansas—porosity of the shallow carbonate zones ranges from 5% to 15%; measures of permeability begin in the millidarcies—compared with shales, which have perms measured in nanodarcies. Net thickness of the formation is between 10 and 100 feet.

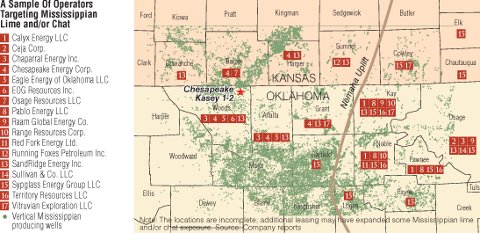

Eagle’s net leasehold over Mississippian was the subject of great industry interest at press time, as its roughly 60,000 net acres were in a data room. Bids this month are to provide other operators and investors with a current, open-market value for leasehold in the western part of the play, where Chesapeake Energy Corp. and SandRidge Energy Inc. have amassed large holdings.

Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. Securities Inc. analysts expect unconventional drilling and completion technology applied to conventional oil formations will make headlines—and possibly companies—this year. “Horizontal moves to conventional activity: If it’s good for the goose, it’s good for the gander. Horizontal drilling—combined with fracing—makes shales productive. So, why shouldn’t that make conventional reservoirs productive? Answer: It should,” the analysts said in January.

Operators have been applying horizontal-well technology to the conventional Granite Wash and Cleveland formations with economic results. Now, they’re targeting the Midcontinent’s Mississippian oil. “If it works, keep doing it. We’ll see more of this in 2011 and beyond,” say the TPH analysts.

SandRidge, Chesapeake, Range

Equity analysts were clamoring for more details about the play in operators’ quarterly conference calls in late February and early March. SandRidge has accumulated between 900,000 and 1 million acres over the Mississippian across northern Oklahoma and southern Kansas—the largest leasehold in the estimated 6.5-million-acre play. Its first 35 horizontals averaged 274 barrels of oil equivalent (BOE) per day apiece in their first 30 days; the most recent averaged 335 and its strongest producer has averaged 856.

Its IPO this spring of SandRidge Mississippian Trust I, with a 49.4% interest in less than 5% of its acreage, will—along with the Eagle Energy asset sale—also provide a market estimate of cost of entry to the play. The IPO is expected to raise $250 million to fund capex, and valuation is expected to be more than $5,000 an acre. SandRidge, which turned its attention to oil two years ago and to Mississippian oil, in particular, in late 2009, accumulated its leasehold for an average of $200 an acre, notes Tom Ward, SandRidge chairman and chief executive.

“While challenging during the process and viewed by many as a contrarian move, we can now look back and see that we not only made the right call on commodities, but we did so in size and scale that has transformed our company,” Ward told investors in a recent conference call.

SandRidge will spend 35% of its $1.3-billion drilling budget this year on the Mississippian; the balance, on its shallow Permian oil properties. At press time, it had eight rigs working the limestone and four drilling saltwater-disposal wells to handle the large water production of those and future wells. In a few months, all 12 rigs will be working the carbonate. Drill time for SandRidge is 21 days, down from 30, and well cost has improved to $2.5 million, down from $3 million.

More than 17,000 vertical wells have been drilled through the Mississippian in the past 30 years, with some 7,000 of these on the SandRidge acreage, Ward notes. Where SandRidge has drilled more than 40 horizontals—primarily in the northernmost reaches of Woods, Alfalfa and Grant counties, Oklahoma—the estimate of recoverable reserves (EUR) is between 300,000 and 500,000 BOE per well, using a hyperbolic decline curve—or “B factor”—of 1.5. Internally, SandRidge is using an EUR of 409,000 per well, 52% oil. It may have more than 4,000 potential drilling locations in the Mississippian based on three wells per section, it reports.

Ward notes many advantages to the play, which is in Oklahoma City-based SandRidge’s backyard. Rigs needed are among the abundant, conventional, 1,000-horsepower type, and for completions, only 10,000- to 12,000-hydraulic-horsepower (HHP) pressure pumping—in great contrast to the 40,000 HHP needed in deeper, tighter unconventional plays.

Fracing is done with fresh water and acid, and proppant is simple Ottawa sand—also plentiful in comparison with steep-demand ceramic proppant.

Ward says, “The entire industry has moved to tight, deep plays that require high-pressure drilling and completions. Consequently, there is an abundance of low-pressure equipment...So we have an excess capacity of equipment when other people don’t.”

SandRidge will drill 138 horizontal Mississippian wells this year for $248 million, plus spend $45 million for 24 saltwater-disposal wells. Most of its acreage has a five-year term, and it expects it could hold a half-million acres by production within that term with a 12-rig program. “We could double our rigs with no issue at all, operationally. It’s just a matter of capital. There are really no logistical issues in the Mississippian,” Ward says.

In February, there were 19 rigs at work on the play, including for Fort Worth-based Range Resources Corp., which holds some 22,000 net acres across the central region in Kay and Noble counties, Oklahoma. Some 50% of its acreage is held by production and it has 108 well locations with potential EUR of 300,000 BOE per well. At a cost of some $2.1 million apiece, the internal rate of return is some 80% at current oil and gas prices, according to John Pinkerton, Range chairman and CEO. Its two Mississippian horizontals tested 24-hour initial potential (IP) at a combined 1,314 BOE per day, 61% oil and 23% gas liquids from about 5,000 feet.

As a great deal of its leasehold is held by production, Range expects to devote only 6% of capex this year toward further proving and producing the formation, while 86% will be spent on its expiring Marcellus shale position.

Range is selling its producing acreage in the Barnett shale—20% of its daily production—to fund 2011 capex. Pinkerton says its Marcellus returns per drilling location are three to four times better than what’s in the Barnett. “That’s what gave us the confidence—along with the Mississippian well…(to) sell 20% of our production…Not a lot of companies do that.”

Meanwhile, Chesapeake’s Serenity 1-3H well in northern Woods County, Oklahoma, came in at 1,609 BOE per day, 84% oil and gas liquids. By October, it had accumulated some 230,000 net acres over Mississippian, and leasing has continued.

Scotia Waterous, which is marketing the Eagle package, estimates that more than 100 horizontal Mississippian wells have been drilled in the past two years. SandRidge has drilled more than 40; Chesapeake, 30-plus; Ceja Corp., approximately 20; Eagle, 18; and EOG Resources Inc., five.

Eastern Stage: Spyglass

Charles Wickstrom has been working the Mississippian vertically since 1978, since he was hired by the late Charles W. Oliphant, the legendary founder of Ceja Corp. in Tulsa, when just out of grad school. “The first Mississippian well I ever caused to be drilled was the Kuhn B No. 1 in Osage County in 1979. It is still producing to this day,” says Wickstrom, managing member of Tulsa-based Spyglass Energy Group LLC.

Oliphant may have attempted the first horizontal in the limestone in 1992 in Northeast Lyle Field in Grant County, he adds, where the rock produces from a fractured zone in the lower 200 feet. “Unfortunately, the technology at that time was not up to the task and the well was unsuccessful,” Wickstrom says. “Charles Oliphant was usually 25 years ahead of everyone else and taught me the value of being first.”

In January 2003, Wickstrom did that, drilling the first successful horizontal into the formation. And, in the past year, he applied the lesson of being first again: The privately held company owns an interest in or controls 478,000 gross acres and 379,000 net mineral acres over the Mississippian in the oilier window of the formation, east of the Nemaha Ridge that runs from Nebraska to Oklahoma City.

It’s possibly the second-largest position in the play—second to SandRidge and depending on how much more acreage Chesapeake has accumulated since it last reported its holding in October. Spyglass’ leasehold is in central and northeastern Oklahoma and southeastern Kansas.

“When we saw what was happening in our own wells, we immediately started acquiring acreage and, being on the east side of the Nemaha Ridge, away from what was getting attention in the western region,” Wickstrom says. “We were able to secure that position before all hell broke loose on the leasing front and really drove up the price.”

His active leasing efforts have wound down. “We have enough to say grace over today,” he says.

What’s on his plate is more than 600 prospective drilling locations on 640-acre spacing. Spyglass was in discussions in early March with potential E&P partners. At possibly $2.1 million per well, if only five frac stages and including saltwater-disposal wells, some $1.5 billion may be needed to fully develop its lease and hold the acreage by production in the next five to seven years. Most of its acreage has a more than three-year term, Wickstrom says.

“There is a lot of interest from financial firms to partner with us, but this program can’t be done just with money. You need people and expertise. A bare minimum of 10 rigs running full time will be required. Then, increased-density drilling will require even more rigs and more personnel.”

The company is owned by Wickstrom and fellow, long-time, Tulsa-based producers Nadel & Gussman LLC, which is operator, and Mike Graves, a second-generation Oklahoma oil man whose father founded and sold Calumet Oil Co. to Chaparral Energy Inc. in 2006. In some acreage, Spyglass is already partnered with former Southwestern Energy Co. executive vice president Richard Lane’s start-up, The Woodlands, Texas-based Vitruvian Exploration LLC.

Wickstrom is using findings from his work in Grant County as a model for Spyglass’ present exploration program. From the 2003 well, he learned that it is critical to design the wellbore to handle the tremendous amount of produced saltwater—at times, 17 times the barrels of oil. The company’s Shaw No. 1A-8H had an IP of 196 barrels of oil and 3,400 barrels of water a day, for example.

“We have seen some of the early wells drilled by shale-gas players not take the volume of water-handling required into account in their initial wellbore designs,” Wickstrom says. “This has limited the drawdown capacity of the pump in relation to the reservoir. Newer wells are being designed to correct these problems.”

In estimating reserves, he knows the vertical wells in the area have historically produced 30,000 to 40,000 barrels of oil. “Knowing that this is a fracture-enhanced reservoir, we use a multiple of four to five times the production of a vertical well for a horizontal well.” Thus, he estimates EUR of 120,000 barrels per well.

Since the Spyglass acreage is in the 100% oil window, these estimates do not include any gas, he notes. It’s all Oklahoma sweet crude, with 38- to 42-degree gravity.

Other operators might estimate 230,000 barrels EUR based on 250 feet of limestone, he adds, but he uses 120,000 because—well, frankly—as an internally funded company, it doesn’t have to prove anything but profitability. “If it’s better than that, terrific, but 120,000 barrels per well are wonderful.”

To date, Wickstrom has drilled six horizontals into the limestone and five saltwater-disposal wells into the deep Arbuckle and basement, in its initial project—Pearsonia West. In Osage County, the project involves a 128,000-acre block it holds in a concession from the Osage Native American tribe, which owns all the mineral rights in Osage County.

The first horizontal attempt went through 13 tri-cone bits to tackle 2,000 feet of lateral. He changed brands of tri-cone; the last lateral was drilled 1,500 feet with only one bit. “We’ve had no success with PDC bits because of the chat content. It’s just too hard,” he says. The limestone, dolomite and chat mix is at least 50% chat. “It’s tough drilling.”

In Osage County, he adds, the formation is found between 3,000 and 3,500 feet, which is shallower than in the western region of the play. Spyglass has two full Mississippian cores as well as microfracture imaging on all of its verticals as well as on four of its horizontals.

It is initially making 2,500- to 3,000-foot laterals. “Those numbers will probably increase as we get into better technology and improve development. As we get up the learning curve, I’m sure we’ll be drilling farther and farther.”

Roughly, operators in the play are applying one frac stage per 400 or 500 feet of lateral to date. As in the western region of the play, proppant is sand, he says.

In terms of infrastructure, there is sufficient take-away capacity, although more will be needed as the play develops. The vast, lightly populated leasehold often lacks roads to access drillsites or electricity to run water-disposal pumps. But, Wickstrom says, it includes the Tallgrass Prairie National Reserve, home to thousands of wild horses and bison, protected by the Bureau of Indian Affairs and private entities. Like the oily leasehold, “it’s a beautiful spot.”

Eastern Stage: Sullivan & Co.

Bob Sullivan’s 102,000 acres abut Spyglass’ in Osage County and are also a concession from the Osage tribe. In late February, the family-owned, Tulsa-based Sullivan & Co. LLC was fresh from the biannual NAPE prospect show in Houston, as was Wickstrom, where the Mississippian was a hot topic.

The company has drilled 50 Red Fork wells in its Osage concession and 25 Simpson wells. The Red Fork sits above the Mississippian and Simpson sits below it. When drilling to Red Fork, which is also known as Burbank, Sullivan presciently took all of his vertical holes deeper into the Mississippian limestone and chat, which is at about 3,200 feet on his acreage, for a look. He completed them uphole, so the company has Mississippian potential behind pipe currently in those 50 locations, plus in his 25 Simpson wells.

“It’s as good as it gets in terms of mapping. We never have any surprises,” says Sullivan, principal and the second of three generations working the Osage County region. He describes it as largely an engineering play.

“The nature of the risk in this horizontal play is not really in terms of what you’ll experience with the drilling phase; the risk comes in whether you can successfully frac it and produce it without big cost overruns and if you can get rid of the water efficiently. It’s really an engineering play.”

The company’s 155-square-mile concession with the tribe in western Osage County began with 80 square miles it picked up in 2000 when Chevron Corp. relinquished its rights over it. Initially, Sullivan was looking at the Simpson. “It’s a familiar story: We came in with new technology in an old producing province.” Of the 25 Simpson wells, 18 produced. “We made some money.”

Meanwhile, the company attempted two horizontals in the Mississippian seven years ago—without modern horizontal drilling and fracture techniques. They both met with hole problems. “In the first, we put a hump in the 3,000-foot lateral in the first 500 feet, so only the first 500 feet are open to production.” Without fracing the well, it IP’ed at 40 barrels of oil a day and lots of water. “We think the hole collapsed around that hump. So it wasn’t a very good read, not a very economic outcome. It will pay out over time, but it’s not what we came for.”

A second horizontal met with similar trouble, but it is performing better. “Both of those were drilled before Packers Plus and other modern completion technologies were mature. So what we have from our own experience is only those two, murky pieces of evidence.”

For greater evidence, he turns to Ceja Corp., a neighbor both in office building as well as in acreage, and that has drilled 20 horizontals into the Mississippian chat in Osage County. In a presentation by the traditionally quiet Ceja to a geologic association, it reported that its 20 Mississippian horizontals—including the best and the worst—have an average EUR of about 70,000 barrels of oil.

“They didn’t frac any of them,” Sullivan says. “We figure—and they probably figure—that, if you make 70,000 barrels without any treatment, then, with a modern frac, you ought to get at least twice that—maybe more.”

On its 26,000-acre Wildcreek project, Sullivan is seeking a financial or E&P partner for up to 80 horizontals, which he estimates may cost $2 million each. Water-disposal wells may run as much as $1 million each. Plans are to commence the lateral in the middle of the naturally fractured limestone and turn up into hard chat, so the frac affects both rocks in a “toes up” configuration that Sullivan likens to the Nike swoosh.

“We’re pleased with the evidence we have of what kind of reserves can realistically be expected in Wildcreek, and what is key to our situation is that we have this large acreage block tied up.”

And, he is encouraged that the play doesn’t appear to be wildcatting.

“We’ve been through a lot of feverish plays during the past 40 years. This one seems to have legs on it, and for two reasons. First, we are pursuing significant reserves that are predominantly oil in a favorable oil-price environment. And, second, it is a clear-cut technology play. Without modern fracturing techniques, this play wouldn’t mean a lot.”

Northern Stage, Kansas

Bob Murdock and partners took another vertical look at the Mississippian chat in southern Barber County, Kansas, beginning in 2005. They had worked the area in the 1990s, and divested the position when rolling several partnerships up into the IPO of Rockies-focused Petroglyph Energy Inc., which has since gone private.

Holding 25,000 acres thus far in two townships, it continues to lease and Murdock, president of Hutchinson, Kansas-based Osage Resources LLC, notes that, without revealing prices, six months ago, acreage costs were a tenth of what they are now.

Its first horizontal is to kick off this month with a 4,000- to 5,000-foot lateral and eight frac stages, using a proprietary proppant within zone, for a total cost of some $2.5 million. “We’re kicking off the program this spring. We’ve been preparing for about two years, and now we’re ready,” Murdock says.

Osage’s horizontal expectations are based on the performance of its 26 vertical wells, each approximately one mile apart, across its leasehold. From these vertical wells alone, with five years of production history, the EUR is about 110,000 BOE apiece, he says.

Murdock expects Osage’s acreage may hold 78 million BOE, about 55% oil and gas liquids. “All these verticals are oily or laden with liquids. It’s a nice position to have.” Osage has 130 undeveloped horizontal drillsites over Mississippian and another 100 that are prospective for horizontal production from other reservoirs. Osage holds its acreage 100%, top to bottom.

“The Mississippian is not the only target, but we believe it is a real company-maker for all of us.”

Like Spyglass and Sullivan, Osage is looking to bring in a drilling partner to develop its leasehold and expand it. “I’m not sure how many we’ll be able to drill this year. We might drill as few as four and as many as 12.”

It’s unclear yet whether the Kansas side of the play is any more or less prolific than the Oklahoma side, he adds. “I believe it’s going to be very similar in terms of the total hydrocarbons that can be produced from a horizontal well.”

But water production appears to differ. “We simply don’t see the large water production that we’ve heard about from some of the players developing along the border in Oklahoma.”

Because the chat is heterogeneous, porosities in the Barber County play can range from zero to 25% within short distances. Murdock says that’s why horizontally tackling the formation is key to unleashing its further bounty. “You end up not putting your wellbore only in an impermeable zone or a zone that lacks porosity. You are able to drill through the heterogeneity.”

West and East, Chaparral

Also holding acreage—and the promise of Big Oil from the Mississippian—is Chaparral Energy Inc. The Oklahoma City-based, privately held company was in the midst of a financial restructuring in 2009-10, and is fully loaded now with free cash flow and debt capacity. It holds some 16,000 net acres in two townships in Woods and Alfalfa counties, Oklahoma, and as much as 30,000 gross in Osage County—all of it held by production in the play area.

This conventional story in a midstream-laden area may have an unconventional problem, however. “The farther east you move in the play, the more issues you’ll have in terms of pipelines and even roads,” says Mark Fischer, chairman, CEO and president.

Another issue is as simple as electricity supply. “These wells typically make a lot of water, and to run these submersible (dewatering) pumps, you need electricity—and three-phase electricity, at that. On our Mississippian horizontal, we have a generator running the pump.”

Chaparral is excited about the play, though, and is adding to its holding, which is pushing past $1,200 an acre in northern Oklahoma. “We hope we can build a much bigger position. This is better than a shale play,” he says, referring to permeability, porosity and the somewhat shallow depth of the formation. But, he cautions, “It’s an emerging play.”

The horizontal test Chaparral drilled recently into the Warsaw interval of the Mississippian in western Oklahoma is making 300 barrels of oil, 800,000 cubic feet of gas and 2,000 barrels of water per day. The vertical depth is about 5,000 feet; the lateral length, approximately 3,500 feet. It was completed with an eight-stage frac treatment.

The test well was designed for a 4,200-foot lateral, but it was stopped short and the frac stages cut back from 10. The frac was with water and sand. “It turned out very well.”

Neighbors’ laterals are between 2,500 and 4,800 feet, and the trend is to longer laterals as production is indicating yet more economic drainage is possible with greater exposure to the zone. Since Chaparral’s leasehold is held by production and it doesn’t have to rush to drill, it plans to spend $5 million on two or three Mississippian wells this year with partners, and to continue leasing while other operators further develop best practices in the play.

Fischer expects EUR per well across its western-play acreage is going to be some 200,000 BOE. Porosity is as low as 4% in some of the tighter limestone, Fischer says; 15% in the more dolomitized area, and as much as 50% in the chat in the Oswego County area. Permeability can range from 1 millidarcy to 50. In the Warsaw interval Chaparral tested, porosity was 15%. Without a core sample, though, permeability is unknown there, he says.

“What is the best producing interval? The Warsaw seems to be one. The tighter limestones are still being proved up, and the chat in the Osage County area, we’re unsure about right now. Time is going to tell. I would advise caution, but early results are definitely of strong interest.”

Western Stage, Eagle Energy

Industry is anticipating initial open-market valuation of some western Mississippian leasehold with bids due this month for approximately 60,000 net acres over some 85,000 gross in Woods and Alfalfa counties, offered by Eagle Energy.

Steve Antry, CEO, and the Eagle team were working the deeper Hunton Lime play horizontally over its acreage in mid-2009 with funding from Riverstone Holdings. A long-time Oklahoma operator, Antry’s Beta Oil & Gas Inc. provided the publicly traded platform for Floyd Wilson’s newest E&P, Petrohawk Energy Corp., in 2004.

In building his own, new start-up, Antry consolidated nine Hunton Lime players in a short time with only one hold-out—New York-based US Oil and Gas Holdings LLC, which remains a working-interest owner in most of the acreage and is, obviously, excited about the potential value of its holding. Eagle estimates it has 350 prospective horizontal Mississippian drilling locations on its leasehold, based on 160-acre spacing.

Getting Eagle started, the team drilled two Hunton horizontals in February 2010 as gas prices were dropping, although it was getting a bonus for that because the Hunton was making 1,400 Btu per thousand cubic feet of gas.

“As gas prices began to drop, we had begun evaluating the Mississippian limestone that SandRidge and Chesapeake were drilling with varying degrees of success,” says Mike O’Kelley, Eagle chief operating officer. As the Mississippian was behind pipe in Eagle’s wells, it began reentering, looking at different points in the shallower formation. “We put our Hunton project on hold.”

Antry says, “The Hunton is really good and solid. It’s not going anywhere. And we like having that, but it’s become our secondary asset.”

After the early results, it picked up an additional 20,000 acres by drawing on Riverstone’s $250-million equity commitment. It has supplemented capital outlay with just under $100 million of bank debt, led by Societe Generale and including Key Bank and Union Bank.

After 18 wells, Eagle has posted the highest IP to date: in excess of 2,000 barrels of oil and about 3.2 million cubic feet of gas. Total reserves over the acreage are estimated at more than 60 million BOE, about 50% oil. Gross company production is 8,400 BOE per day, with the Mississippian making about two-thirds of that; the balance, Hunton.

O’Kelley says, “Going back into the limestone, we realized there was very little depletion of the reservoir by the vertical wells. These horizontals that we, SandRidge, Chesapeake and others are drilling have virgin pressures and IPs.”

Eagle’s laterals are roughly 3,500 feet and fracs are seven stages. O’Kelley says, “I think the economic break today is somewhere between 3,000 and 4,000 feet. You get into diminishing returns as you extend that lateral, although you won’t know this with certainty until you see the production over five years.”

All-in, including water disposal, costs are about $3 million per well, for an EUR of 425,000 BOE per well. “So it’s extremely economic,” Antry says. “We’re at 100%-plus rate of return. And, the repeatability is there for that kind of ROR in this play.”

Eagle is also using Ottawa white sand in its completions. O’Kelley says, “We’re at about 6,000 feet, so we don’t need any resin-coated or top-shelf proppant. I don’t think the sand has any real effect of propping the rock, either. We don’t need it to. We have nice permeability.”

Initially, the rate of decline appears to be similar to SandRidge’s estimate, which is a B factor of 1.5. “We level out at 100 to 150 barrels a day,” O’Kelley says.

Gross thickness of the Mississippian under its leasehold is 500 feet. Eagle has been drilling its laterals through the top 60 feet of the Mississippian that is mostly limestone, making less water and more oil and gas. “Deeper than 100 feet, then we’re having to get more water out of our way,” O’Kelley says. “There are areas of the Mississippian that are predominantly water with gas and oil, and then some areas that are gas and oil with some water.”

Water production can be as much as five barrels per barrel of oil, and this ratio declines to 5:2 in time. But, the persistent water production is desirable, O’Kelley adds. “As long as you’re moving fluid through it, you’re moving gas and oil.”

He notes another of the play’s attributes—no need for seismic. He worked the nearby, deeper Woodford shale for Newfield Exploration Co. through 100 of these wells. “A critical issue we had is that we had to have seismic to delineate the faults. It’s critical to the drilling success. In the Mississippian, however, we have data from, literally, thousands of vertical wells.

“We’re working strictly off mud logs. There’s a whole cost component that isn’t even here to be able to access this resource.”

Antry says Eagle’s work at proving its leasehold is done, thus the sale that is expected this spring. “We feel like we’ve pretty much delineated the acreage we have. It’s as contiguous as you can be out here.”

Next Stage?

Where does the play end? Acreage is being leased and existing holdings are being considered from Comanche to Chautauqua counties, Kansas, and from Woods to Osage counties, Oklahoma. As the Mississippian sits nearer to the surface in the east than in the west, that trend continues even farther east.

Wickstrom notes that, in those eastern-most counties, the formation becomes politically complicated by acreage that is held by coalbed-methane production at as few as 2,000 feet.

The oil is still good, though. Wickstrom says, “You’re still in the 30-plus gravity range, and it’s sweet.”

In February, a publicly held producer that isn’t active in the Mississippian play was quizzed about it by analysts in a quarterly conference call. The producer has some acreage over the chat and limestone, but its executive vice president said the company hasn’t been pursuing it.

"We looked at that sometime back and elected not to get aggressive there," he said. "There are some things there that we were just unable to understand…If we missed that one, it goes on our list of plays we missed."

Contact the author, Nissa Darbonne, at ndarbonne@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

LNG, Crude Markets and Tariffs Muddy Analysts’ 2025 Outlooks

2024-12-12 - Energy demand is forecast to grow as data centers gobble up more electricity and LNG liquefaction capacity comes online in North America, but gasoline demand may peak by 2025, analysts say.

Predictions 2025: Downward Trend for Oil and Gas, Lots of Electricity

2025-01-07 - Prognostications abound for 2025, but no surprise: ample supplies are expected to keep fuel prices down and data centers will gobble up power.

DOE: ‘Astounding’ US LNG Growth Will Raise Prices, GHG Emissions

2024-12-17 - The Biden administration released Dec. 17 a long-awaited report analyzing the effects of new LNG export projects, which was swiftly criticized by the energy industry.

Dallas Fed: Trump Can Cut Red Tape, but Raising Prices Trickier

2025-01-02 - U.S. oil and gas executives expect fewer regulatory headaches under Trump but some see oil prices sliding, according to the fourth-quarter Dallas Fed Energy Survey.

Paisie: Trump’s Impact on All Things Energy

2024-12-11 - President-elect Donald Trump’s policies are expected to benefit the U.S. oil and gas sector, but also bring economic and geopolitical risks.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.