McKinsey’s analysis comes as companies and countries across the world seek lower-carbon energy resources to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The goal is to limit the global temperature from rising more than 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels by 2050. (Source: Shutterstock)

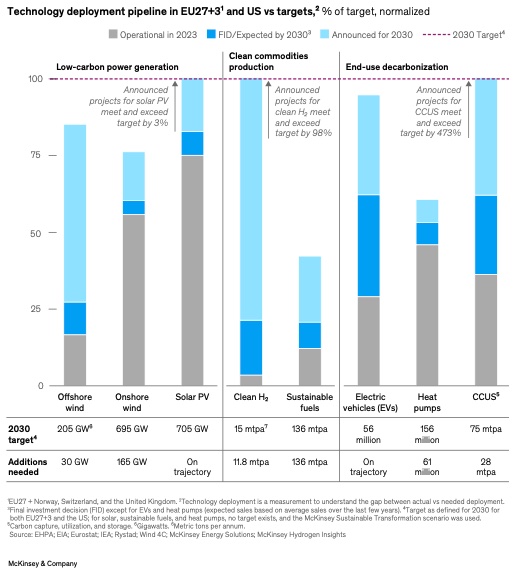

Despite regulatory moves in the U.S. and Europe, as well as progress on renewable power projects, deployment of low-emissions technology is only at about 10% of levels required to hit net-zero targets by 2050.

A report by consultancy McKinsey & Co. highlighted the so-called “widening reality gap” between decarbonization technology project commitments, progress made so far and what’s still needed.

The U.S. and Europe will need to add more capacity—nearly 200 gigawatts (GW) in wind capacity additions alone for example—to reach 2030 targets. Targets missed this decade could jeopardize net-zero 2050 ambitions. Much hinges on crucial final investment decisions (FIDs), when companies commit to projects by allocating funds.

With easier projects tackled, the more difficult decarbonization levers are left to pull. However, most companies have been slow to open their wallets and push the plethora of their project announcements from paper to reality.

For some projects, especially those dependent on building up a robust supply chain and market or reliant on technologies that haven’t reached at-scale deployment, the economics don’t pencil.

McKinsey’s analysis comes as companies and countries across the world seek lower-carbon energy resources to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The goal is to limit the global temperature from rising more than 1.5 C above pre-industrial levels by 2050. Decarbonization pathways include hydrogen, carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS), renewables and sustainable fuels, but the road to development has been bumpy.

Scaling technology, strengthening supply chains and incentivizing demand while keeping energy reliable, affordable—and for developers, profitable—are among the challenges.

“Transforming the energy system hinges on the coordinated deployment of interlinked and interdependent technologies. A slowdown in deployment in one area of the energy system can cause cascading delays and hamper the growth of other technologies,” said Humayun Tai, senior partner at McKinsey. “This data confirms the reality gap that we believe the industry is experiencing, especially through inflation and system shocks alongside geopolitical uncertainty, which is seeing international supply chain tensions and trade disruptions. It further underscores the need for companies to reassess the current strategies to further drive the transition.”

The McKinsey report, which focused on the U.S. and Europe, points out that there have been significant investment announcements, but many have failed to reach FID.

Awaiting more FIDs

The report shows that in the U.S., more than 1,000 green or blue hydrogen projects have been announced since 2015. Fewer than 15% have reached FID, which McKinsey said indicates a high risk for a project to fall through.

“Decarbonization technology projects have historically had a high fall-through rate, with only a small percentage of announced projects reaching FID, and an even smaller numbers of projects actually being realized,” the report shows. “Our analysis shows that many planned projects for key decarbonization technologies in the European Union and the United States are falling short of announced targets, some significantly so.”

Similarly, Europe’s pipeline of solar projects is off track for meeting 2030 capacity targets of 600 GW. Less than 390 GW of planned capacity is expected online by the end of the decade. Plus, of the approximately 114 GW of additional capacity expected online within the next five years, less than 20% has reached FID. It’s still possible to catch-up, McKinsey said.

Solar has been booming in the U.S., but McKinsey analysis projects that momentum will slow after 2028.

“Of the announced capacity to come online before 2030, around 60 percent is still pending FID, putting a significant proportion of planned solar at risk,” the report states. “However, again, here we would acknowledge that the nature of solar installation is such that the pipelines could indeed materialize in time.”

The story appears bleak for U.S. offshore wind, which has been rattled by unfavorable market conditions but is still adding capacity. “The United States currently has about 1 GW of installed offshore wind capacity—far off its national targets, which aim for 30 GW by 2030,” according to the report. “The 17 GW of offshore wind capacity that has been announced to come online by 2030 still only represents 60 percent of this goal—of which, 90 percent are still in the pre-FID phase.”

Offshore wind capacity is faring more favorably in Europe, where a more mature markets exist. Here, offshore wind development has a gap of only 18 GW left to meet its overall 2030 target.

In the U.S., only 39 GW of offshore wind capacity is expected to be online after 2025. Of that, 16 GW, or 41% of the total pipeline, has secured FID.

For CCUS, the U.S. pipeline expects 170 million tonnes per annum (mpta) of capacity, but 132 mpta of projects lack an FID.

In Europe, 60 times the current CCUS capacity is due online by 2030 with a pipeline of 148 mpta—yet 44 mpta of potential capacity is still awaiting FID.

“Facing this hard truth, innovation and policy resets will be needed for the increasing number of country and company net-zero commitments to be achieved in practice and move projects to FID and quickly beyond to subsequent deployment,” according to the report.

Breaking through barriers

Governments in the U.S. and Europe have rolled out legislation and funding to incentivize development, and many companies have moved forward with projects.

However, several other factors are at play and may be behind the delays.

These, according to McKinsey, include challenging macroeconomic environments; technology and business case maturity; lack of reference projects; long permitting procedures; specialized labor shortages; raw material shortages; and geopolitical uncertainty.

The report concluded that the U.S. and Europe risk missing crucial climate targets across critical technologies, creating a ripple effect that would hinder 2050 net-zero goals.

Despite the widening gap, there is still a chance for governments and companies to act, according to Thomas Hundertmark, senior partner at McKinsey.

“Doing so will require revaluation of existing strategies and regulatory regimes, many of which were devised to assume a different economic and policy landscape than exists today,” he said. “With a clear view of the reality gap emerging, now is the time for stakeholders across the energy value chain to revisit decarbonization plans to pioneer the next wave of progress.”

Other steps the analysts said could de-risk developments include forming partnerships; actively engaging in discussions; addressing offtake and infrastructure needs; and staying on top of developments by adjusting strategies based on market intel and sector developments.

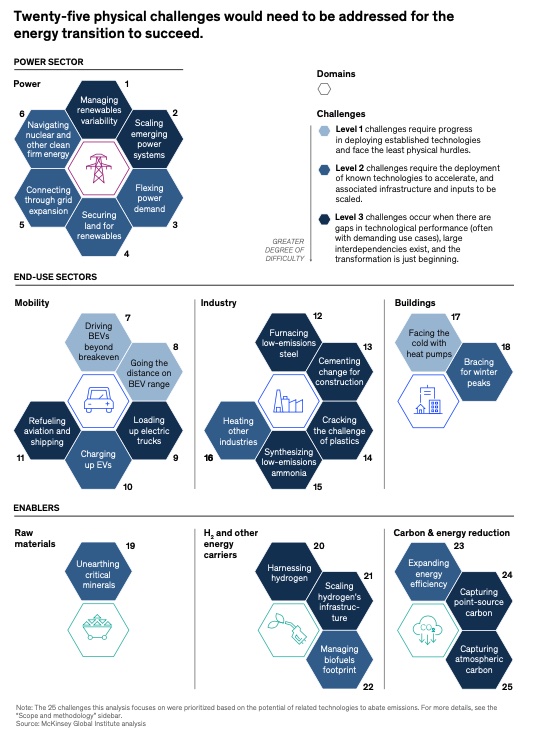

In all, McKinsey identified more than two dozen physical challenges that must be addressed to make progress. These physical challenges relate to developing new low-emissions technologies and actually switching high-emissions infrastructure and processes to lower emitting ones.

“Addressing these physical challenges would involve improving the performance of low-emissions technologies, addressing the interdependencies between multiple challenges, and achieving massive scale-ups, even in technologies where a strong track record has not yet been established,” McKinsey said in the report. “And, of course, this is only one side of the equation. To overcome these physical challenges, significant firm investment into low-emission technologies needs to be unlocked.”

McKinsey plans to release more analysis on the topic, focusing on technology deployment, policy, and incentives as part of its Global Energy Perspective.

Recommended Reading

Saudi Aramco Discovers 14 Minor Oil, Gas Reservoirs

2025-04-10 - Saudi Aramco’s discoveries in the eastern region and Empty Quarter totaled about 8,200 bbl/d.

Analysts’ Oilfield Services Forecast: Muddling Through 2025

2025-01-21 - Industry analysts see flat spending and production affecting key OFS players in the year ahead.

SM Energy Marries Wildcatting and Analytics in the Oil Patch

2025-04-01 - As E&P SM Energy explores in Texas and Utah, Herb Vogel’s approach is far from a Hail Mary.

Winter Storm Snarls Gulf Coast LNG Traffic, Boosts NatGas Use

2025-01-22 - A winter storm along the Gulf Coast had ERCOT under strain and ports waiting out freezing temperatures before reopening.

US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Eight Weeks

2025-01-31 - For January, total oil and gas rigs fell by seven, the most in a month since June, with both oil and gas rigs down by four in January.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.