Chord Energy could be the quintessential example of what other E&Ps are trying to achieve in the recent lightning round of upstream M&A. Poised to become the Williston’s largest producer upon completion of its acquisition of Enerplus—expected at the end of May—leadership gears to take the best of every practice it absorbs. Shareholders have taken notice and the firm’s stock price is soaring, with expectations of more upside by year end.

How did a company that didn’t exist in 2021 do it? CEO Danny Brown tells Deon Daugherty, Oil and Gas Investor editor-in-chief, how it all came together and what’s next for the emerging behemoth in the Bakken.

Editor’s note: Chord Energy closed its deal to acquire Enerplus Corp. on May 31.

RELATED

Chord Closes $4B Enerplus Acquisition for Williston Basin Scale

Chord Juggles Closing $4B Enerplus Deal, Plans to Drill 4-mile Laterals

Deon Daugherty, editor-in-chief, Oil & Gas Investor: Walk us through the genesis of Chord Energy.

Danny Brown, president and CEO, Chord Energy: You’ve got to go back into the legacy organizations. I came into Oasis [Petroleum] in April of 2021. We were through the depths of COVID, through the Saudi-Russia oil price wars, but still in the midst of a very, very heavy investor focus on ESG and certainly a lot of questions about the durability of the industry and the durability of our product.

Like many E&P companies at the time, we were somewhat struggling for relevance. We were a very small-cap company in a basin that was [given] as much attention as those companies within the Permian Basin.

Both Whiting and Oasis had entered restructuring into 2020. After the COVID demand loss and the Saudi-Russia price wars, it was a terrible time with negative oil prices and high debt. So many companies couldn’t make it through. They both went into bankruptcy and both got new boards and hired new CEOs. I was hired on the Oasis side, and I think both of us—the CEO of Whiting Oil & Gas and myself over at Oasis, as well as our boards—realized that we were subscale at our current size. I think it was my second day on the job that I called the CEO of Whiting.

DD: What was that conversation like?

DB: Well, there was just a recognition that we were two small companies fighting for investor relevance. We had assets that were beside one another within the basin, and we discussed the strategic merit in investigating whether or not a combination would make sense. And we both agreed that it would, but we also both agreed that we had a lot of work to do for ourselves before we could really seriously pursue something.

So, we both went on a “journey of self-help” for ourselves. [Oasis] had an asset in the Permian Basin, which was acreage that we liked, but it had some drilling commitments associated with it and it really distracted us from where we wanted to focus our attention, which was in the Bakken. We divested the Permian position [and] we picked up a position in the Bakken from QEP.

Diamondback previously had bought QEP really for their West Texas acreage. They also picked up their Bakken acreage. It didn’t fit that fantastically within Diamondback’s portfolio. And so they ended up selling that asset. We picked that up.

We announced these within a few days of one another. We had sold our Permian position, but we increased our Bakken position by 50%. That was a big part of our portfolio cleanup to position us to do the next big thing.

DD: The next big thing?

DB: Well, Oasis Petroleum had an affiliated midstream, separately traded company called Oasis Midstream Partners, OMP. And we recognized that we were not seeing the full value of that midstream company within our company. Generally, a midstream company will trade at 7x-8x EBITDA, whereas an oil and gas company at the time was trading, let’s call it between 3x-4X EBITDA.

The risk of the cash flows is less for the midstream company because you’ve got contracts guaranteeing those cash flows, and generally those cash flows command to higher multiple. Well, here we had this huge midstream company that Oasis owned outright, but we were trading as if we were only an E&P company and we didn’t have these other cash flows in it, so we weren’t realizing the full value.

It would be hard for someone to do a merger with us because we would say, “Hey, you need to recognize the value there.” And they’d say, “Well, the value’s not in your stock price.” We needed to do something about that. The second big thing we did after we did the portfolio repositioning from an asset standpoint is we merged our OMP holdings into Crestwood Equity Partners, which was a pure-play midstream company.

DD: That’s a lot of work within a fairly short amount of time.

DB: We didn’t want to sit on our hands. Another thing we were really active about was a really progressive and forward-leaning return of capital program back to our shareholders. There’s a lot of companies that have done that now, but when we did it, I think we were one of the first ones to come out to the degree that we did. And we got a lot of good attention from shareholders along the way.

The combination of making these other strategic moves was largely applauded by investors. They loved the focus for us back in the Bakken, they recognized the trap value we had with OMP. Combining the two organizations made us more resilient. It was an all-equity deal. And so, both sets of shareholders participated in the upside in the pro forma organization. And we were able to wring out synergies from the deal, which we thought would be around $65 million when we announced between Whiting and Oasis, but turned out to be $100 million of synergy annual savings. Both sets of shareholders benefited from that. And because we were larger, more investors were noticing us.

Slowly, our share price went up. And as we went through the integration, we said, well, that’s great. We’re twice the size that we were before. We’re a new company. We really did try to do something new, not have this be Oasis 2.0 or Whiting 2.0—let’s be something new as we move forward.

RELATED

Whiting, Oasis Petroleum Become Chord Energy as Merger Closes

As we went through the integration, we made sure that all of our systems, all of our processes, would be scalable so that if we potentially double in size again, we would be able to do that fairly easily. And I think that’s paying dividends now for our transaction with Enerplus.

DD: So, you doubled in size, and then Enerplus is another big add.

DB: [Enerplus is] about half our size currently. When I came into this role in April of 2021, there were three, not quite pure-play, but three almost pure-play Bakken companies that were all about the same size: Enerplus, Whiting and Oasis. And from an outsider’s perspective, it made so much sense to me at the time that they should all be part of the same company.

DD: What have been the challenges along the way?

DB: No integration is easy. We tried to take a “best of” approach as we build core. And one of the nice things about being a new CEO to Oasis is that some of the legacy practices, the legacy processes and the legacy way of doing things, candidly, I didn’t have an emotional attachment to them because they weren’t a product of something that I’d come up with. I probably had an opportunity to be a little more unbiased around those things and no need to defend my previous way of thinking.

And the CEO on the Whiting side was in the same boat. It really unshackled us as we put the two organizations together.

If there’s a great process that Oasis is implementing, let’s keep that. And if there’s a great process that Whiting is implementing, let’s use that. And if we find out in this process that really neither one of them is a best practice, well let’s ditch them both and go to option C and we’ll move forward. Those were the marching orders given to everyone.

I think that’s the harder way of doing something as opposed to saying, “Well, we’re just going to adopt company A’s or company B’s practice and we’re going to jam everything together.” That’s the easier way to do it. It’s probably a less risky way of doing it, but I don’t think you have as strong as the potential value that you can get out of a deal. I wanted to get every bit of value out of the deal as we could. It wasn’t just the assets that I was looking for, but also the processes and then maybe catalyzing some new thinking within the organization.

DD: How did Enerplus become part of the equation?

DB: Well, bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better, but there’s more ways to be better if you’re bigger. I think my counterpart at Enerplus had some similar feelings.

On occasion, I would speak with the Enerplus CEO, and we would have discussions about that. Was there strategic merit to putting our two organizations together? And I’ll say, ultimately, both sides saw that there was, and we were able to put something together that I think really made sense for all parties. I think the most telling thing is that it’s a 90% equity deal, which means that their side really believed in the future of the company because they’re betting their equity stake on the future performance of the company.

RELATED

Williston Warriors: Enerplus’ Long Bakken Run Ends in $4B Chord Deal

DD: What makes the Williston special in your view? You divested your Permian assets, but the Permian gets the industry excited. Why do you want to be the behemoth in the Bakken?

DB: I am an oil bull. I like oil. Not to say I don’t like natural gas and other forms of energy. I’m a hydrocarbons guy, but I think oil is a great commodity to be involved in. And the Bakken really is the oiliest basin of the major unconventional basins around. The proportion of oil we produce is higher than any other basin.

As a comparison, the Permian is a much larger basin and it produces about five times the oil that’s produced in the Bakken. But it also produces about seven times the gas that’s in the Bakken. And so, it’s a gassier basin than we’ve got within Williston.

We’re only really going after one zone. We’re a middle Bakken and development player generally. And so you can imagine all the stack pay zones that are in the Permian, which are fantastic from a resource potential standpoint. But it also leads to some uncertainty on what the deliverability is going to be. And then there are all of the things that have been talking about, certainly increasing conversations over the past, say three or four years on parent-child relationships offset drainage both vertically and horizontally. We just don’t deal with as much of that here. We’re not developing as densely as it’s developed within the Permian, and we’re only really developing in one zone.

DD: What are the challenges of operating in the Bakken? When you talk about ensuring that your processes are scalable, to what end?

DB: When we put Oasis and Whiting Petroleum together, at the time we were both a little under $3 billion in market cap. We put these together, we made a company that was over $5 billion in market cap that still struggled for relevance, to get attention.

As you mentioned, there is much more focus on the Permian. I like many things about the Bakken, but there’s not as many investor eyes on Bakken as there is in the Permian, despite some of the advantages. When we went into this, we said, “Well, we need to be bigger, and so we need to be on the lookout.” We’re the product of consolidation. By putting Oasis and Whiting together, we need to continue to look at that as we move forward.

What we didn’t want to do is create a solution that worked great for Chord, but was limited in its applicability. Say you’ve got an accounting system that can only handle so much data and now you’re running it ragged. Maybe it was working fine for Chord, but if we were 50% bigger or a 100% bigger, it just wouldn’t have the bandwidth in order to be able to accomplish that. So, let’s not lock ourselves into that. Let’s recognize that if we can grow sensibly, we should look to do that. Let’s make sure that the systems are scalable in order for us to do that.

DD: I’ve read that Chord has something like $586 million allocated toward M&A if the opportunity arises. Is that accurate?

DB: We don’t really have a slush fund set aside for M&A, but what we do have is a balance sheet that’s very strong. We are sitting right now essentially unlevered. We’ve got debt, but we’ve got an equal amount of cash to offset that debt. We’re sitting essentially unlevered as an organization, but we have capacity to put a significant amount of debt on the organization if we think it’s the right thing. So, one of the first things they’ll teach you, one of the first things I learned when I went to business school was, leverage isn’t necessarily a bad thing so long as it allows the organization to enhance returns while maintaining a comfortable margin of safety from a risk standpoint.

DD: Would the intent be to remain a pure play in the Williston or Bakken?

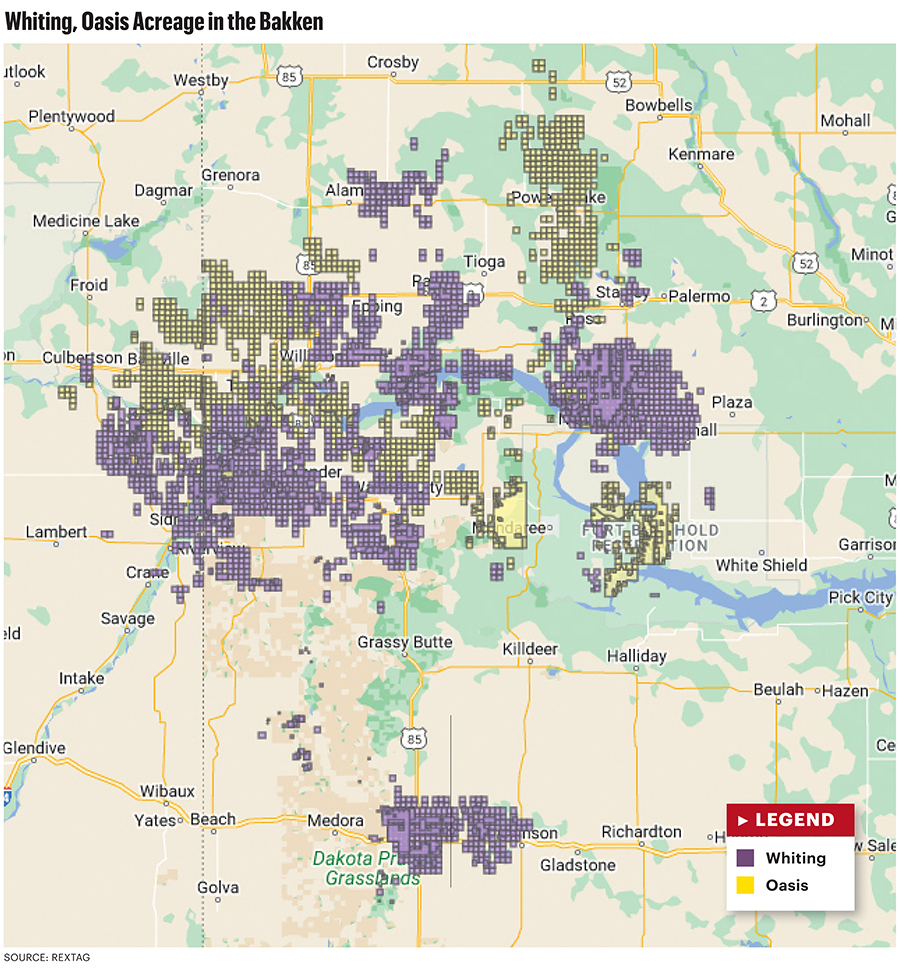

DB: It’s a sensible question. I think the bar for us to consolidate within the Bakken is low relative to the bar for us to go outside the basin. And it’s for all the reasons you think: We know the basin really well. We’ve got over a million acres in the basin, so we stretch from east to west, from north to south; we kind of touch every part of the basin. Anything that we would acquire in the basin we’re probably going to be adjacent to or very close to, which means not only will we know the subsurface there, and so we will know what we’re getting into, but there’s probably true operational synergies that we can wring out of it too.

There’s a lot of operational synergies we would have within the Bakken. We know that regulatory environment well, we’ve got field offices up there, we’ve got all of our supply chain put in place and so we can get services. If you go out of a basin, you don’t have all of those same things.

It’s important to clarify that we look at opportunities out of the basin, but we’re pretty clear-eyed about the risk of going out of basin.

DD: Have generalist investors decided that perhaps oil and gas isn’t going away?

DB: It’s certainly so much more encouraging than it was two years ago. We couldn’t get a meeting with the generalist investor two years ago. We’re getting more meetings now. We’re seeing certainly more what I would say larger names and more passive investments within our stocks certainly. Larger organizations seeing more and more interest as you get bigger. I think it’s not what it was 10 years ago, but it’s a far cry from where we were two or three years ago.

And so I do think generalist investors have some interest in the space. Now, regaining some interest in the space doesn’t necessarily mean investing as heavily as they did before. We’re certainly not back to that spot.

DD: What else should we know about the Chord story?

DB: One thing that I’m really excited about is we have been able to—not only streamline our operations position ourselves to do some of these big strategic transactions—we’ve also done a lot of work internally.

I’ve talked about “self-help” in the context of getting ourselves prepared to do a big deal, but I didn’t talk as much about the most important self-help that we’ve done to focus on how to generate high returns within the assets that we have.

So, forget doing a deal with Whiting, forget doing a deal with Enerplus. How do we ensure that the capital efficiencies and margins of our existing asset base are as high as they can possibly be? And we’ve seen tremendous success with that.

DD: What excites you about Chord’s future?

DB: We have widened the spacing of our development. One of the things we recognized is that in the early time of the basin, we were likely developing too closely together with our different wells. And as we were developing too closely together, we were overcapitalizing. And so, just by definition, for a given amount of oil, we were spending too much capital.

On a per-section basis, we were generally drilling our wells, call it between eight and 12 wells per section. And we’re probably between four and six wells per section now. Almost half the number of wells that we would’ve done previously and still getting essentially the same amount of oil out of the ground. And so you can imagine how much more capitally efficient that program is.

Now you can accelerate some value by putting more sticks in because you get it quicker, but over the long term, the rate of return you’re going to get is far superior if you do it by widening out. We’ve combined widening out our well spacing with drilling longer laterals.

DD: How does this translate to your shareholders?

DB: It’s a combination of our base dividend and the variable dividend that we declare every quarter and then share repurchases. And so, 75% of the free cash flow that we generate every quarter will go back to shareholders in a combination of those three methods. But you can’t have good return of capital unless you have good return on capital in the first place. You’ve got to make money in the first place. Return on capital is the foundation of everything.

Recommended Reading

Early Innings: Uinta’s Oily Stacked Pay Exploration Only Just Starting

2025-03-04 - Operators are testing horizontal wells in less developed Uinta Basin zones, including the Douglas Creek, Castle Peak, Wasatch and deeper benches.

Williams Cos. Targets Lewis Shale After $307MM Green River JV Buyout

2025-04-14 - Williams Cos., known as a midstream company, is landing laterals in the oily Lewis Shale after completing a $307 million buyout from a joint venture partner in Wyoming’s Wamsutter Field last year.

SM’s First 18 Uinta Wells Outproducing Industry-Wide Midland, South Texas Results

2025-02-20 - Shallow tests came on with 685 boe/d, 95% oil, while deeper new wells averaged 1,366 boe/d, 92% oil, from two-mile laterals, SM Energy reported.

Follow the Rigs: Minerals M&A Could Top $11B in ’25—Trauber

2025-04-15 - Minerals dealmaking could surpass $11 billion in 2025, fueled by deals in the Permian and in natural gas shale plays, says M&A expert Stephen Trauber.

Oklahoma E&P Canvas Energy Explores Midcon Sale, Sources Say

2025-04-04 - Canvas Energy, formerly Chaparral Energy, holds 223,000 net acres in the Anadarko Basin, where M&A has been gathering momentum.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.