Sequitur Energy Resources’ two-pad drilling rig on University Lands’ well in Irion County, Texas, is targeting Wolfcamp B in the Permian Basin. (Source: Ricardo Merendoni/Hart Energy)

[Editor's note: A version of this story appears in the November 2018 edition of Oil and Gas Investor. Subscribe to the magazine here.]

At the dusty intersection of U.S. 67 and Texas 163, across from a rail line, stands tiny Barnhart, Texas—an outpost on the fringes of the southern Midland Basin.

Beyond closed storefronts, a jumble of machinery and a windmill, a horse trailer is covered by Mars red rust.

This is Irion County, Texas’ southwest corner, which opens up to a big and empty West Texas prairieland. Barnhart arguably lacks probable cause to still exist. It was first a last-gasp railroad town in the 1910s, and later, an oil town besieged by a bust in the mid-2010s.

Yet not far off, oil and gas are flowing—despite the miles separating this Midland from the prestigious core in areas to the north.

It’s here that Sequitur Energy Resources LLC has set up part of its shop in the Permian Basin. Sequitur CEO Scott D. Josey took the initiative to look at a number of distressed and bankruptcy-related transactions in 2016, despite the crushing downturn in oil prices.

“Just because things aren’t so great, it doesn’t mean that there aren’t opportunities, and so, you still have to get up every day and do your best,” Josey told Oil and Gas Investor.

Eventually, the company would purchase its Permian home from a premiere seller that it couldn’t resist: EOG Resources Inc. (NYSE: EOG).

The E&Ps stationed on the boundaries of the Delaware and Midland basins persist. Some produce well results that pose larger, existential questions about what it means to be in the core: monster IPs or solid, low-decline performance.

The Permian is a once and future kind of basin. For nearly 100 years, operators have retaken the land, coaxing out production through vertical drilling, then horizontal wells and now through science, efficiency and precision. Like one of history’s most conquered cities—Palermo, Italy—the Permian may surrender to new things, but it never seems to stop giving.

Today, the southern Midland is knocked for its gassiness, particularly as it slopes off to the south. But the area played a crucial role in the Permian’s development and is credited by some for hosting the first wells into the Wolfcamp Formation—a discovery that would eventually send companies scrambling farther north and deeper into debt.

But there’s plenty of oil there. The lower Wolfcamp B, which encircles most of Regan, Upton and Irion counties and dips down into Crockett, holds an estimated 1.4 billion barrels (bbl) of oil, a 2016 U.S. Geological Survey assessment found.

In the Delaware, PCore Exploration & Production LLC ventured to the southern boundary of the known Delaware Basin, where prospects become less certain, information scarcer and risk more acute. There it snatched up disregarded, underperforming wells. While PCore’s wells are unlikely to mimic the monster IPs seen to the north of its acreage, initial decline rates have been impressively shallow, said CEO Mark Hiduke.

The company entered the area with the understanding it was taking a calculated risk, not a blind leap of faith. The company’s technical team had scrutinized offset wells, some dating back as far as 2013—an eternity in the Permian’s continued technology evolution.

In the southern Midland, companies are pushing boundaries in Irion, Crockett and Reagan counties. In far-southern Reeves County, Texas, exploration is extending deeper into the southern Delaware Basin. Even the Central Basin Platform is home to management teams with past Permian successes on their résumés that are testing.

Discounting such areas can be shortsighted and expensive. Diamondback Energy Inc. (NASDAQ: FANG) agreed in August to pay $1.25 billion in cash and stock for Ajax Resource LLC. The company’s acreage includes 21,000 net acres in northwest Midland and northeast Andrews counties.

Ajax purchased the assets about three years ago from W&T Offshore Inc. (NYSE: WTI) for $376 million. On a gross basis, that suggests a gross payout to Ajax of more than three times its acquisition costs.

In 2015, Ajax bought leasehold “viewed by the industry as the northernmost edge of the basin, and only the lower Spraberry was considered prospective,” Ajax executive chairman Forrest Wylie said in a news release. “I am proud of Ajax’s ability to prove up and execute on a very successful multizone program delivering repeatable, highly economic well results that compete favorably anywhere in the basin,” he said.

Interest in the outlying areas of the basin make sense, and not just because of lower acquisition costs, said Pablo Prudencio, U.S. Lower 48 upstream analyst for Wood Mackenzie. Top-tier area wells aren’t inexhaustible.

“Our analysis shows that really massive wells are becoming less common in the top-tier ZIP codes,” Prudencio told Investor. “For companies potentially looking for a few company-making completions, this could impact where they drill.”

From a strategic viewpoint, companies are also likely to prove up land near that of companies that are natural consolidators.

The steady uptick in oil prices has also played a role in reopening the hinterlands to drillers.

“It’s natural for focus areas in shale plays to get larger with rising prices,” Prudencio said. “Sweet spots expand and contract all the time. That said, Permian activity is still massively concentrated. Half of Reeves County has close to 80 active rigs, so I wouldn’t say we’re establishing new focus areas at any great scale.”

But there’s also a brash confidence in oil explorers. Hiduke chose acreage in Reeves County by design. He was attracted by the promise of the acreage but also the possibilities of expanding the basin’s core.

“Our goal, to be honest, has always been to go where others haven’t and to new portions of the play as quickly as we can,” Hiduke told Investor. “And to be able to build upon the work that the industry’s done in general, that's our real goal.”

The Comeback

Like a chalk outline, the muddy road follows a methodical path past solar-powered, automatic fences, a tank battery and an occasional baffled cow.

On the horizon of the University Lands, the derrick of Sequitur’s two-pad apparatus rising over the flat plain, seems as anachronistic as a cell phone tower obliquely captured in a photo of the Old West.

Closer, the rig commands the world by sound alone. It endlessly revs and hums with power, chewing through 156 feet of earth and rock each hour.

Sequitur staked out this claim and the rest of its Permian acreage on the outskirts of the southern Midland in a September 2016 deal with EOG. At the time, Irion County had mustered two vertical rigs. In September 2018, the county had nearly six rigs running, all of them drilling horizontal oil wells, according to data collected by Baker Hughes Inc. (NYSE: BHGE), an affiliate of General Electric Co. (NYSE: GE).

Many E&Ps pulled back rigs during the downturn, particularly in 2016. As drillers returned, they’ve benefited not only from higher commodity prices but also from advancements in completion technology.

“As activity returns to those areas years later, we often see significant improvements in well productivity due to more effective completion designs,” Prudencio said.

Following the winter of 2014, activity drained out of areas on the periphery of the basin. In the southern Midland, Irion, Crockett and Reagan counties ran a combined 57 rigs, according to Baker Hughes data. By 2016, Irion and Crockett ran a single rig each and Reagan ran five. As of June 2017, rig counts had nearly recovered from the 2014 levels in Upton and Reagan counties while still lagging in Irion and Crockett.

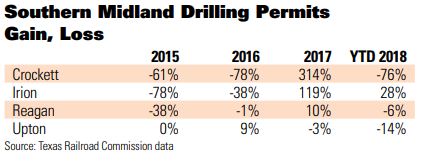

Similarly, approved drilling permits in Crockett, Irion and Reagan counties dipped a cumulative 64% before rebounding in 2017, particularly in Irion and Crockett. Upton permits remained relatively stable.

Sequitur runs two rigs, one in Irion and the other in Reagan.

Josey said the southern Midland’s reputation as a gas-heavy area often ignores the oil. “Our Reagan County acreage is low GOR [gas-oil ratio] and 80%-plus oil,” he said. “Our Irion County assets are around 30% oil, but those wells come online initially with production at around 80% oil.

“You’re fairly close to the bubble point in the reservoir in Irion County, and the GOR does increase over time,” he said. “If you don’t actively drill, the production will become gassier but with a lot of liquids. However, gas only accounts for around 10% of our revenues and about 70% of our revenues come from oil, even though it’s only about 40% of our overall production.” Sequitur is not alone on the southern edges of the Midland Basin. Companies such as PT Petroleum LLC, Fleur de Lis and Triple Crown Resources LLC are also targeting the Southern Midland.

PT Petroleum holds 63,769 contiguous acres in the corner pockets of southwest Upton and southeast Reagan counties, straddling the Crockett county line to the south for 19 miles. The company calls the acreage its Trinity Project.

In June, CEO Cory Richards told Investor that its Wolfcamp C well stood to be transformational, not merely for the company’s Trinity Project but the southern Midland Basin as a whole.

In April, PT Petroleum unveiled results for the well, the Orange 6091C. In six months, the well produced 130,000 bbl of oil. The results were on par or better than Callon Petroleum Co. and Parsley Energy Inc.’s Wolfcamp C wells to the north, with a third-party engineering firm predicting a 900,000 bbl EUR with a GOR of less than 500 to 1.

In a May presentation, 15 Trinity Area wells highlighted by PT Petroleum showed that all but two produced 85% oil or greater.

Richards said the well results set up a large-scale development opportunity.

“Very shortly after we got positive results on the well, we drilled three Wolfcamp C delineation wells,” he said.

New Old Hands

The breadth of the nearly empty water pit and its 18-feet depth seem like an oversight of terrestrial planning. In time, the 3-million-gallon reclamation and recycling pond, covered with multiple layers of black material rolled out by hand like an enormous shroud, is expected to save Sequitur on water costs.

Sequitur has busily ramped up its facilities in the basin—signs of a recovery in the oil industry and also in the bottlenecks in piping crude out of the basin.

Along with its water system, the company was completing construction of two 10,000-bbl oil tanks—part of an elaborate storage and transportation system that will tie into a nearby rail line. The company intends to move oil out by rail and help beat differential costs as high as $15/bbl.

Some of Sequitur’s staff and management have spent years working in the Permian. Like many E&Ps returning to the far-flung reaches of the Midland and Delaware basins, Sequitur is not a newcomer.

The company is led by former members of Mariner Energy Inc.’s executive team, an E&P known more for its Gulf of Mexico assets that merged with Apache Corp. in 2011 in a deal worth more than $4 billion.

Less well-known is Mariner’s early pioneering work in the Permian, where it once held 150,000 net acres that today would be “considered core of the core and very valuable,” Josey said. Mariner’s successes included the discovery of the Midland’s Deadwood Field in Glasscock and Howard counties.

In 2008, the company assembled a 70,000-net-acre position in the Deadwood for a pittance: about $250 to $300 per acre.

“We were one of the first players in the eastern part of the Permian,” Josey said.

At the start of 2011, Deadwood produced about 2,000 bbl/d of oil and 6 million cubic feet per day (MMcf/d) from 58 delineation wells. By 2013, its volumes had mushroomed to 25,400 barrels of oil equivalent per day (boe/d), including about 15,300 bbl/d of oil.

Sequitur was off and running a matter of months after the Apache transaction with a new name but the same investment strategy: a focus on rate of return, cash flow and contiguous acreage with running room.

At first, Sequitur weighed transactions in the $3-to $5-billion range. “We probably submitted offers on roughly a total of $20 billion worth of corporate-type transactions,” Josey said. “We got close on a couple of deals, but nothing came to fruition.”

Sequitur also pursued smaller transactions with a concentration on the Permian, but acreage costs had increased as much as a hundredfold since Mariner’s time in the basin.

The company passed up some opportunities because they were just too scattered. In retrospect that might have been the wrong call, Josey said, since the Permian Basin has become one of the hottest basins on the planet.

“It takes a while when you’re starting over from scratch,” he said. “We looked at a lot of deals.”

In 2013, Sequitur headed into uncharted territory, buying about 60,000 net acres in East Texas’ Buda-Rose play. The area held stacked pay Josey saw as somewhat “Permianesque.” The oil content ranges from 80% to 85% of production, he said.

“Our East Texas position was what I would call an emerging play and we were certainly pushing a boundary, but we felt that we were in a good area,” Josey said, noting that its position was adjacent to acreage controlled by EOG Resources, “a company that we highly respect.”

By the time the downturn began to play havoc with producers in the Lower 48, Sequitur felt that there should be an opportunity to take advantage.

In June 2016, Sequitur acquired from EOG a position in the southern Midland Basin, primarily in Reagan and Irion Counties, Texas, as well as parts of northern Crockett and Schleicher counties, Texas.

Through a number of bolt-on acquisitions, Sequitur expanded its position to more than 77,000 “mostly contiguous acres,” he said.

Josey is quick to acknowledge the challenges of operating in southern Midland, which still gets a bad rap. But he feels fortunate to have purchased the properties when it did and believes that there are more opportunities in the area.

Sequitur Energy’s centrally located tank battery in Irion County, Texas, separates produced water from oil recovered from the Wolfcamp B.

Other industry luminaries such as Steve Chazen, former CEO of Occidental Petroleum Corp., have liked the southern Midland Basin as a potential home. Chazen looked at the area before settling down in the Eagle Ford and forming Magnolia Oil & Gas Corp.

In an April interview, Chazen told Investor he saw a number of small, largely unknown operators and an area that offered consolidation opportunities.

“There is a lot of oil in place there, and it should work,” Chazen said. “Sometimes it’s technique.”

Sequitur’s techniques appear to be working just fine. In less than two years, the company has more than tripled its production to more than 27,000 boe/d from the Permian. The acreage has provided good results and economics as the company has applied modern completion production techniques and benefited from improving commodity prices.

“Our position may not be in the deeper part of the basin, but it’s in a very good spot in the basin,” he said.

The Bogeyman

The Grand Canyon Skywalk, a horseshoe-shaped glass bridge, allows tourists to venture out 70 feet from the canyon wall, offering a brave view of 4,000 feet of rocky chasm.

In the Permian subterranean, such distances are trifling. So it was with PCore’s first well, the Graef 1-12 #1HA, drilled out to an unassuming 4,711 feet in the lower Wolfcamp A in Reeves County.

The test well, drilled far to the south, is a stunner—not because of an earth-shattering first day or even 90-day results, but rather its relentless, nearly unflagging production.

In nine months, the well has produced more than 120,000 bbl of oil.

“We’re thrilled,” Hiduke said. “Based on our math and running [results of] all the different wells, it’s in the top 20% of all performers per lateral foot of oil in the Delaware Basin.”

Hiduke doesn’t expect to mimic the monster IPs seen to the north of PCore’s acreage. What’s been most impressive is the shallowness of its decline rate, with production averaging 300 bbl/d of oil.

“Right now, our southernmost well and our acreage is one of our best looking logs” in the Permian, he said. “We’ve gotten more excited about some of the acreage that’s farther south of our position.”

Beginning in 2016, PCore bought into the southern Delaware expecting a one-interval play, expanding out to 35,000 net acres. PCore added more acreage in 2017 and closed an acquisition this year following about a year of negotiation.

“The reason we were able to enter this position was because of poor performing wells drilled in older, ‘vintage’ completions techniques,” Hiduke said.

The position’s wells weren’t stellar, but PCore’s technical team, after a rigorous study, liked the geology.

“Even though some of the results were not compelling, that was due to any number of various factors,” he said. Time had not been kind to the vintage completion methods used.

PCore surmised that the area clearly needed tighter cluster spacing, more pounds of sand per foot and more water. Add the right chemical mix, get the pump schedule right, and higher recovery factors were realistic.

As with its operations in the southern Midland Basin, PCore would pick its landings carefully, bring in modern completion techniques and “tweak” where to land wells. PCore had previously developed a Midland Basin position in Upton, Reagan and Glasscock counties. The company sold to Parsley Energy in 2016 for $148.5 million.

“Our feel-good factor was that all the wells that were of older vintage, but still had the right variables there, were still good performers and were still economic at the time.”

The company also found decent pressure, which Hiduke called “one of the original bogeymen that we did not have enough data on.”

“That was kind of more of a bet on our side that the pressure was going to be there. And what we found was a really tight shale that had great deliverability,” he said.

The Graef delivered nothing short of remarkable results after it was put online at the end of 2017, quickly surpassing PCore’s optimistic outlooks. So far, the well has delivered 20% above production expectations, Hiduke said.

More tests also led to greater comfort. PCore found higher than projected oil-in-place. It found thicker reservoir in some of the areas than originally projected, 350 to 400 feet in thickness in the Wolfcamp A with more than 70 million standard barrels of oil per section and 30 MMbbl in the Wolfcamp B.

Following the unyielding success of the Graef well, PCore is now fracking its first well, the Stallion, on its Pecos County acreage, with completion expected in October. The company chose Pecos after the first appraisal well’s results.

“We decided to start delineating the acreage and then really growing cash flow by attacking from west to east as we are right now,” he said.

PCore plans to end 2018 with about six to seven producing wells as well as three drilled uncompleted wells.

Hiduke said the company often takes inspiration from other exploration-oriented operators such as Brigham Resources LLC, which first built its position in Pecos and used science to improve efficiency.

“We’re looking to do something very similar here,” he said. “Just to be able to build on that knowledge base of what’s out there in the industry and try to accelerate going from your initial test well.”

Permian Pushback

Permian stardom can be fleeting.

In Barnhart, a diner called The Oil Can is carefully stocked with idiosyncrasies: a taxidermied deer and wild boar, pool tables and a small sign warning that police will be called, regardless of who starts the fight.

Not too long ago, the building housed Sawyers, a feed-vet-hardware-hunting supply and pipe fitting store.

Pushing the Permian boundaries in coming years will be all about understanding formations that are shallower or deeper than those being actively developed today, WoodMac’s Prudencio said.

“This involves more than simply knowing that the formation is present, but more importantly, understanding the optimal completion design and ideal well spacing for long-term development,” he said. “Operators are becoming more and more active in this department across both the Midland and Delaware Basins.”

For instance, Pioneer Natural Resources Co. has conducting appraisal work in the Wolfcamp D and different Spraberry zones this year. In the Delaware Basin, Matador Resources Co. plans to test the Wolfcamp D and Third Bone Spring formations this year.

“These are two examples out of many,” he said.

The Permian constantly changes, expanding and contracting to the north and south, just as it has done in the past.

“If you think about the original maps of the Midland Basin, most of Howard County was left out,” he said. “That’s where the highest transaction values have been recently, in Martin and western Howard counties.

“But it took a couple of years beyond the initial explosion of the Midland Basin play to really showcase that,” he said. “I think we’re kind of getting there now, to the southern extent of the Delaware and we’re starting to see that north as well as you start to expand these areas, where you look into landing zones and completions, really unlocking a lot of value here.”

He suspects other companies are also looking to push the boundaries through frack design and other innovations.

“I think things will continue to move and evolve in that way, and I think a lot of the edges of these basins will start to really look attractive when you start seeing prices above $60, and when the Midland to Cushing differential shrinks in 2019.”

Sequitur finds itself rolling with the punches and thankful for its advantages.

“When the Mid-Cush differential deteriorated, we were able to secure a rail option to the Gulf Coast that should substantially improve our economics until the oil takeaway issue is resolved. Not many companies, particularly companies of our size, can pull that off,” Josey said.

Josey credits Sequitur’s private-equity-backer, Acon Investment LLC, which supported Sequitur not only in East Texas during the downturn, but also doubled down to “buy these assets when we did.”

“They deserve a lot of credit for staying with us,” Josey said. “I know there have been other PE-backed firms that when things got bad, the sponsors turned off the tap.”

Sequitur entered the basin, like many other private companies, hoping to find resources, develop them and sell them or launch a public company.

“These are the same things that every private-equity-backed firm thinks about; however, it seems that we have been dealing with a weird market ever since, including roller-coaster commodity prices and lack of equity capital markets,” Josey said.

Nevertheless, the company expects to be free-cash-flow positive by the second-half of 2019, assuming projections are right.

“We begin to throw off a fair amount of cash thereafter,” he said, “which we feel is a great accomplishment.”

Considering all the E&Ps on the edge of the Permian map, an accomplishment indeed.

[SIDEBAR]

Cinderellas And Pumpkins

The rep of the Southern Midland Basin—a giant gas field with marginal value—is hard to shake.

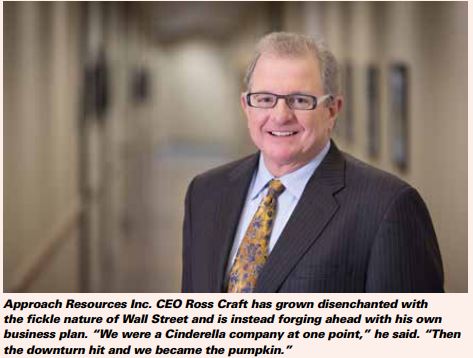

Ross Craft, CEO of Approach Resources Inc. (NASDAQ: AREX), is frank and unapologetic about the position he’s been working since 2002 and which was recently expanded with a roughly 40,000-acre bolt-on acquisition in an area the company calls Pangea West. The deal was funded through equity.

Craft has a somewhat jaded view of Wall Street, which has prized and spurned Approach’s value, particularly since 2010. As one of the first companies to discover the Wolfcamp Shale, Approach’s position has remained essentially fixed as perceptions moved it from cutting-edge (at $38 per share in 2012) to the fraying edges ($2 per share in 2018).

“There are a lot of Cinderella companies out there, and we were a Cinderella company at one point, in 2011 through 2014,” he said. “We were in full-scale development and then the downturn hit and we became the pumpkin.”

Approach has persisted through several downturns, in part because of its engineers and geologists, but also because it was the Permian’s first practicing detective agency.

Approach formed in 2002, and about a year later entered into a farm-out agreement covering about 48,000 acres located in northeastern Crockett County, Texas, in a field called Ozona Northeast.

Four years later, the company made a 50-MMboe Canyon discovery in an area located roughly 7 miles northwest of its Ozona Northeast Field.

“We found a canyon tight gas reservoir that had been overlooked” Craft said. “We were in the northeastern part of Crockett County, about 5 miles south of Irion County, in an area where there had not been much activity.”

The company drilled close to 500 vertical gas wells, ranging in depth from 8,000 to 9,000 feet, from 2004 to 2010 using compressed air and foam.

Unlike fluids, any type of subsurface hydrocarbon flows the air encountered would show as drilling flares. “We would often get robust oil and gas shows from the Wolfcamp Shale as we drilled through it on our way to the targeted deeper formations,” Craft said.

Though Craft’s focus at the time was on tight gas due to attractive gas prices, signs of something else beneath his leasehold sparked his curiosity. “Most companies in the area, at the time, didn’t run a full suite of openhole logs, only running a gamma ray-temperature log across the targeted formation, and they seldom acquired mud logs for the full wellbore,” Craft said. He ran a full openhole logging suite and used mud loggers on at least one well per section of land prior to setting production casing.

What Craft had found were the first “shows of the Wolfcamp.”

During the economic crisis of 2008, natural gas prices fell from a high of $10.79 in July 2008 to below $3 in September 2009.

“As a result of the falling gas prices, it was necessary to explore other opportunities,” Craft said.

“We were looking at a way to rebrand the company, so we started looking at the Wolfcamp Shale. Through our vertical program we collected a large amount of data across the Wolfcamp Shale.”

About the same time, Broad Oak Energy and EOG Resources had started to venture into the Wolfcamp. Broad Oak entered Irion County and EOG settled in just north of Approach.

As it happened, the majority of Approach’s acreage “had the Wolfcamp underneath it,” he said. The company embarked on a series of Wolfcamp tests and modeling exercises in the Permian beginning in 2009. In October 2010, the company announced the Wolfcamp Shale discovery to a large group of investors and analysts in New York.

As development got underway on the Wolfcamp, however, the expense of wells grew exponentially.

“We started out slowly,” he said. “We went from drilling vertical wells at $800,000 to drilling $8.6-million horizontal wells. So it had to work.”

For a time, Approach was rewarded by investors for its southern Midland assets.

By the start of the downturn, toward the end of 2014, Approach had fallen from investor favor. A&D activity flared up in the northern Midland and, later, the Delaware Basin.

“The market basically turned a deaf ear to the southern Midland Basin,” Craft said.

He recalled analysts telling him that IPs being reported by operators in other parts of the basin were far better. Craft could only respond that it wasn’t about IPs but total returns.

Craft has no regrets about his position. Instead, he plans to focus on his business plan: reduce debt, improve efficiency and expand his footprint in the southern Midland Basin. The company has strengthened its balance sheet and reduced long-term debt by $127.1 million, eliminating $35 million in future interest expense in 2017.

The company has focused on lowering lease operating expenses (LOE). In 2017, such costs were down 35% since 2014. The company ended 2017 with LOE of $4.23 compared to the company’s peer group, with $5.75 to $6 in similar costs. And that’s in an area where, since 2010, more than 2,000 horizontal wells have been drilled.

Along with advancements in technology, Approach’s rate of return on its wells ranges from the high teens to as high as 40% based on May 2018 strip pricing. Company wells typically produced 65% liquids with EURs averaging north of 700,000 boe.

The company also foresaw the need for robust infrastructure. Since 2012, it has invested more than $100 million in infrastructure. The infrastructure system is 100% company owned. Gas is still a meaningful product for the company.

“I joke around, gas keeps the lights on,” he said.

But gas is a fact of life in the Permian, and it will continue to increase in the basin with time.

“Whether you’re in the northern part of the basin or the southern part, increasing GORs will be realized by all operators, it is simply a mobility issue within the fracture network.”

Since most of the Midland Wolfcamp is a normally pressured reservoir, liquids will have a harder time moving through the nano and microfractures due to the size of the liquid molecules.

“Gas molecules, on the other hand, are quite small and able to move through the nano and microfractures with little effort,” he said. “We predicted this in 2013; it’s just the nature of the beast.”

The company has moved into newer phases of resource recovery, noting that recoveries within the basin are low, ranging from 2% to 5% oil and 7% to 12% gas. That only means a lot of hydrocarbons remain trapped.

Approach has started experimenting with a variety of enhanced recovery techniques including miscible gas flooding. In early 2015, the company also modified its completion designs with tighter stage spacing, more sand and fluid per lateral foot.

In mid-2017 the company incorporated nanoparticles in the stimulation fluids.

”Originally, we utilized metal oxide particles through the stimulation treatment, but recently we switched to silica oxide particles,” Craft said.

First-year cumulative oil production from the original three wells treated with nanoparticles lifted the company’s type curves to 700,000 boe.

The average first-year cumulative oil production from the three wells, each in a different Wolfcamp bench, “exceeded our new type curve with the A bench well outperforming the oil type curve by 93%,” Craft said.

As an early mover in the play, Approach has roughly 140,000 net acres at an average cost of about $500 per acre. That compares to peers in the northern Midland, where stellar results require investments of up to $60,000 per acre.

The majority of Approach’s core Wolfcamp acreage is held by production, which allows it to match its development pace with commodity prices. Though the southern Midland is shallower in depth, Craft noted it also has the thickest productive shale section in the basin.

Craft muses that perhaps the southern Midland simply needs to be rebranded. Could consolidation be the key?

“Any consolidation opportunities within the southern part of the basin, ranging from small complementary bolt-ons to larger accretive acreage positions, that can be assimilated, we’ll definitely look hard at that. We know the basin as well as anyone,” Craft said. “Looking at total returns and the vast amount of hydrocarbons in place, I think the southern Midland Basin is a good place to be, especially for low-cost operators who can think outside the box.”

Darren Barbee can be reached at dbarbee@hartenergy.com.

Recommended Reading

E&P Highlights: Dec. 16, 2024

2024-12-16 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including a pair of contracts awarded offshore Brazil, development progress in the Tishomingo Field in Oklahoma and a partnership that will deploy advanced electric simul-frac fleets across the Permian Basin.

E&P Highlights: Jan. 21, 2025

2025-01-21 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, with Flowserve getting a contract from ADNOC and a couple of offshore oil and gas discoveries.

Watch for Falling Gas DUCs: E&Ps Resume Completions at $4 Gas

2025-01-23 - Drilled but uncompleted (DUC) gas wells that totaled some 500 into September 2024 have declined to just under 400, according to a J.P. Morgan Securities analysis of Enverus data.

New Jersey’s HYLAN Premiers Gas, Pipeline Division

2025-03-05 - HYLAN’s gas and pipeline division will offer services such as maintenance, construction, horizontal drilling and hydrostatic testing for operations across the Lower 48

Wildcatting is Back: The New Lower 48 Oil Plays

2024-12-15 - Operators wanting to grow oil inventory organically are finding promising potential as modern drilling and completion costs have dropped while adding inventory via M&A is increasingly costly.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.