Rendering of a clean hydrogen electrolysis production site. (Source: U.S. Department of Energy)

Backers of the Pacific Northwest Hydrogen Hub (PNWH2) are on a mission to replace diesel and other fossil-derived fuels and products with hydrogen—where it makes sense.

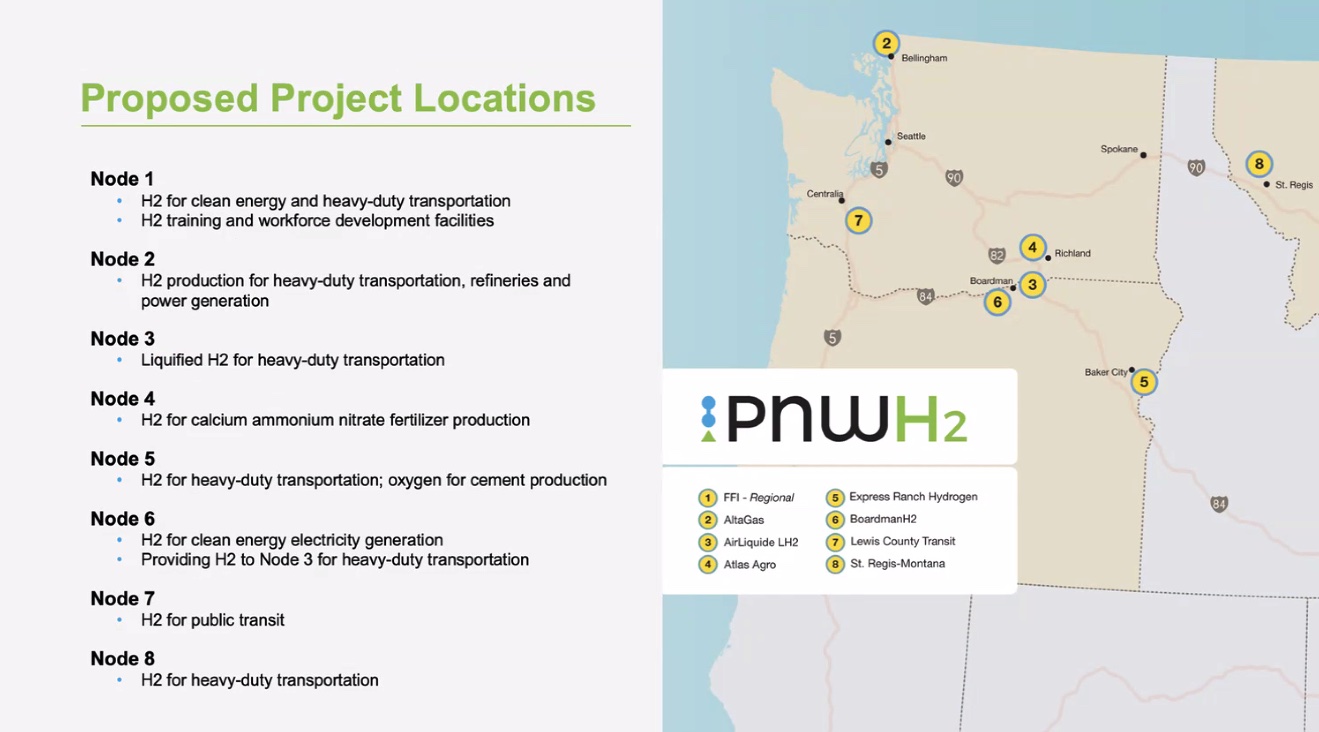

The hub, which includes about eight project locations called “nodes” across Washington, Oregon and Montana, is specifically targeting hard-to-abate industries. Strategically positioned along the region’s major thoroughfares, the projects seek to replace fossil fuels used in public transit, agriculture products, medium-and-heavy-duty transport and electric power with hydrogen.

But it won’t be easy, given the hub—one of seven selected to be a part of the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs Program—has committed to using electrolytic hydrogen. At present, electrolytic hydrogen faces stiff competition from lower-cost fossil fuel-based hydrogen, which doesn’t rely on renewables for electricity and the energy-and-water-intensive electrolysis process that use electrolyzers to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen.

Then, there is the supply and demand dilemma.

“This hydrogen hub program is not going to be easy to do. We have to basically create supply and demand for a new energy commodity at the same time. And that’s not been done as far as I know, any time recently,” Chris Green, president of the Pacific Northwest Hydrogen Association, said during a webcast Aug. 21. “There’s a lot of work to do there. There’s no doubt lots of work to make sure that the economics of these projects actually work.”

Lots of money also will be needed.

PNWH2 is one of three regional hydrogen hubs that have been awarded the first tranche of federal funding. In all, the DOE will dole out up to $7 billion to establish the regional hubs. PNWH2 has been awarded $27.5 million of its share of up to $1 billion.

Hydrogen, which has near-zero greenhouse gas emissions, is seen as a solution to climate woes, serving as a route to decarbonize hard-to-abate sectors and reduce reliance on fossil fuels used in transportation. Combined, the hubs are targeting more than 3 million metric tons of hydrogen per year. The hubs, which put producers near supply and will eventually connect to other hubs, are intended to help bolster the sector.

“It is a quite wonderful thing that the federal government has invested so much money in hydrogen. But, you know, for the $7 billion or so that the DOE has put toward all these hydrogen hubs, there’s another $30 [billion] to $50 billion in private sector funding behind that,” Green said. He added, “We think our hub has a good chance of doing really well, but it’s going to take a little time and effort and vision to try to continue to make this stuff happen.”

Addressing concerns

The webcast gave stakeholders and others a chance to ask questions and gain more insight about the hub and its projects as developers move through Phase One planning, analyzing, designing and engaging with the community.

Concerns included mitigating the impact on limited water supplies in the region.

It takes about 15 kilograms (kg) to 20 kg, or five gallons, of water to produce 1 kg of hydrogen, according to Janine Benner, vice chair of PNWH2 and director at the Oregon Department of Energy. The amount of water required can vary depending on factors such as the type of system used, time of year and cooling water and water purification needs.

“The good news is that electrolyzers … can use potable or non-potable water,” Benner said, noting this includes recycled water, wastewater from treatment plants and desalinated seawater. “Hydrogen is not the only energy resource that uses water. A lot of energy generation is very water intensive.”

The entire PNWH2 hub would use about three Olympic-sized swimming pools worth of water a day, Benner said. “That is the same as 200 acres of typical irrigated eastern Washington farmland. So, it’s significant water use, but it’s not actually inconsistent with other existing uses in the region.”

Each project in the hub is working to secure water rights and working to recycle as much of the water as possible, she added.

Powering up

Others wanted to know whether the region had enough renewable energy to power electrolyzers, especially considering growing electricity demand. Will steam methane reforming—the process used to produce hydrogen from natural gas—be needed?

Steven Schueneman, hydrogen development manager for Puget Sound Energy, said PNWH2 is “solely focused on electrolysis at this point.” Getting a clearer picture on demand and how well electrolytic hydrogen squares up with hard-to-decarbonize sectors from a total load perspective will be needed, he said. That will involve getting insight from policymakers and utilities.

“But to really reach scale, we are going to need more renewable energy,” Schueneman said. “How we can move renewable energy really is a story about transmission pipelines as well as electric transmission lines. There’s a future where both will be required, probably too early to tell how big and what proportion each one of those is going to be. But we are going to need a lot of new energy on the grid here in the not too distant future.”

Green added that with a large amount of electricity demand, including from data centers, “we want to make sure we use it [electricity] as judiciously as possible. … There’s a new era upon us about how we think about our grid and how we think about total energy portfolio utilization because of all the cars we have to electrify and because of all these data centers and because of all the heat pumps.”

Making sense

Being judicious means using hydrogen where it makes the most sense.

“Because we don’t have an unlimited supply and because it is kind of expensive to make and takes a lot of electricity, there’s lots of folks that have an interest and intention to make sure we focus on things that are really hard to decarbonize, things that you can’t just plug in,” Green said.

That’s why PNWH2 is focused on decarbonizing the transportation sector, for example, targeting big trucks, boats, planes, transit buses and other “industrial processes that don’t quite easily lend themselves to just plugging into the grid or plugging into electricity or using a battery.”

End-users in these harder-to-decarbonize sectors is where hydrogen demand is coming from, Green said.

“It’s not just about all our aspirational goals about climate. It is about trying to achieve those goals in the constraints and in the context and confines of what economically will actually pencil,” he said. “So, we have to get hydrogen down to a price that is reasonable and we have to convince customers to buy it. Right now, the places where we think there are customers that will buy hydrogen and make it a viable energy commodity product are those harder to decarbonize uses, and so that’s where our focus has been.”

PNWH2 said it aims to reduce carbon emissions by 1.7 million metric tons per year, roughly equivalent to the annual emissions of 400,000 gasoline-powered cars. The hub intends to produce at least 335 metric tons per day of clean hydrogen powered by at least 95% carbon-free energy feedstock, reaching 100% carbon-free energy feedstock by 2035.

Recommended Reading

E&P Highlights: Feb. 18, 2025

2025-02-18 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, from new activity in the Búzios field offshore Brazil to new production in the Mediterranean.

E&P Highlights: Feb. 10, 2025

2025-02-10 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, from a Beetaloo well stimulated in Australia to new oil production in China.

E&P Highlights: Jan. 27, 2025

2025-01-27 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines including new drilling in the eastern Mediterranean and new contracts in Australia.

E&P Highlights: Jan. 21, 2025

2025-01-21 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, with Flowserve getting a contract from ADNOC and a couple of offshore oil and gas discoveries.

E&P Highlights: March 24, 2025

2025-03-24 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, from an oil find in western Hungary to new gas exploration licenses offshore Israel.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.