John D. Rockefeller figured it out back in 1869. All that was needed to stabilize the price of oil was a mechanism for crude refiners and drillers to agree on a price, then enforce production limits to maintain it.

The 1872 “Treaty of Titusville” between Rockefeller’s National Refiners’ Association and the Petroleum Producers Union in Pennsylvania did just that. It set a price of $5/bbl ($125.28/ bbl in 2023) and a production ceiling of 15,000 bbl/d. This landmark agreement proved that entities normally at odds with each other could make a mutually beneficial deal for long-term gain.

It lasted all of several hours.

“Just as the Treaty of Titusville was inked, discipline among producers once again collapsed and wild drilling resumed,” Robert McNally wrote in his 2017 book, “Crude Volatility: The History and the Future of Boom-Bust Oil Prices.” By January 1873, the market price had fallen to $3.29/bbl ($82.44/bbl in 2023) and spot prices had sunk as low as $2.60/bbl ($65.15/bbl), McNally wrote.

The volatile nature of oil prices has gripped the energy industry—in day-to-day operations and strategic planning—almost since Edwin L. Drake struck oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania, in 1859 and made drilling for crude a viable business.

“It’s always been a cyclical commodity,” Mark Finley, fellow in energy and global oil at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, told Hart Energy. “It’s also been a commodity that has been prone to someone trying to manage it, whether it was the Standard Oil monopoly or the ‘Seven Sisters’ or the Texas Railroad Commission or OPEC.”

Demand for oil is driven in large part by demand for refined oil products in transportation. That component of the equation is inelastic, in that motorists who drive to work are likely to fill their tanks with gasoline whether the price rises or falls. By contrast, a shopper in a grocery store engages in elastic demand. If apples are cheap, apples are bought. If apples become more expensive and oranges drop in price, then oranges end up in the shopping cart.

“The challenge with the oil market as it relates to boom and bust is really the imbalances that we see between supply and demand,” Angie Gildea, national sector lead for energy, natural resources and chemicals at KPMG, told Hart Energy. “As demand changes as the economy expands and contracts, you have changes in consumption and demand, which drives one side of the equation. But then, supply also changes with things like geopolitical events or weather or things like that.”

But unlike demand for oil, supply is elastic. When the price rises, producers have traditionally pumped more of it out of the ground. That greater supply on the market pulls the price down, which eventually motivates lower production. The lower supply creates scarcity on the market, which pushes the price up again. A lot of people make their livings tracking these trends.

Stability at last

Stung by the failure of unruly producers to stick to the Titusville deal, Rockefeller (who went by the code name “Chowder” among business associates) went back to work. In 1875, he organized the Central Association, a group of refiners who agreed to lease their assets to the association in exchange for stock in Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Co.

“In the rate war among the railroads, the Central Association occupied the enormously strategic position of controlling nine-tenths of the refining business of the country,” Gilbert Holland Montague declared in a 1905 article for The North American Review. “The dominance thus gained over the transportation situation firmly established the Standard Oil Company in its present supreme position.”

Rockefeller controlled not just the bulk of the refining sector but the bulk of the oil pipelines in the U.S., as well as a chunk of the country’s storage capacity. A wildcatter seeking to bypass the original oil baron would first need to find a non-Rockefeller refinery to buy his oil, then figure out a way to get it there without access to pipelines or the railroads, whose own robber barons were in cahoots with Rockefeller. Good luck with all that.

In essence, the price of oil was dictated by how much Rockefeller wanted to refine, and how much he was willing to pay to refine it. Excess production was no longer a problem because there was nowhere for the excess oil to go.

The result was the long-sought stability Rockefeller craved. In the 21 years prior to Standard Oil’s overwhelming control of the market, crude oil prices fluctuated an average of 53% per year, according to McNally’s calculations. During the Standard Oil era, with boom-and-bust a thing of the past, that fluctuation was reduced to a mere 24%.

But that control was limited to the U.S. market, and wasn’t destined to last. The oil business had taken off globally and Royal Dutch Shell was developing into a powerhouse. Antitrust fervor in Washington—leading to passage of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act of 1890 and President Theodore Roosevelt’s effective use of it to go after conglomerates— resulted in the dissolution of Standard Oil by Supreme Court decision in 1911.

Texas takes a turn

Rockefeller understood how the oil price roller coaster cut into margins and drove some companies out of business. He cared about the former, not so much about the latter, and did everything he could to try to get it under his control.

When the federal government took control out of his hands, state governments took a crack at breaking the bucking bronco of an industry.

Oklahoma’s first major oil play was Glenn Pool, discovered about 12 miles south of Tulsa in 1905. Overproduction dragged the price down to only 30 cents/bbl. In 1914, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC), an agency of state government, responded by ordering oil from the Glenn Pool field to be priced at no less than 65 cents/bbl. There was no enforcement mechanism so the order was ignored.

The next year, the state legislature authorized the OCC to restrict production in particular fields in which supply exceeded demand. Those restrictions were ignored, as well. The oil business was so lucrative that operators were incentivized to produce more and risk repercussions. Even the declaration of martial law and dispatch of troops into the fields to shut down wells didn’t have much effect.

Texas had more success. The Railroad Commission of Texas (RRC) utilized a series of measures, including quotas on low-cost, highly productive wells that did not require artificial lift, to protect small producers from price busts and maintain stability for the state’s economy.

“Designed to help small, high-cost producers, (the) quota system added to overall oil production costs and kept oil prices higher than they would have been under purely competitive conditions,” McNally wrote.

Business historian William R. Childs estimates that the RRC controlled 35% to 45% of all oil and gas produced in the U.S. between 1930 and the 1970s. That’s a lot of power concentrated in one state government agency, but as far as boom/bust was concerned, it was a success. During that time, the price of oil varied by an average of 3.6%.

“Favoring small producers was economically wasteful, as it led the commission to approve the drilling of thousands of wells that were marginal producers,” the Texas State Library and Archives Commission says on its website. “The extra investment spurred exploration, but it also contributed to higher costs…. In the long run, these costs would hurt the ability of Texas oil to compete with foreign imports.”

That foreign oil was coming from the Middle East. And there was a lot of it.

Feelings of energy insecurity

The sheer volumes needed to satiate the world’s thirst for fossil fuels in the booming 1950s and 1960s shifted much of the global oil market power to producers in the Middle East.

In the years following World War II, seven large international oil companies (Exxon, Gulf, Texaco, Mobil, Standard Oil of California, BP and Shell), dubbed the “Seven Sisters,” pretty much controlled global production and price. In the mid-1950s, for example, the Seven Sisters in the Middle East held 12% of the world’s oil supply off the market to keep prices steady, McNally wrote. Some 23% of global output was held off in the U.S., mostly in Texas by the RRC, during that time.

Middle East oil was owned by the Arab countries but they had to strike deals with the Seven Sisters to produce and sell it. By the 1970s, they made clear they were done negotiating and would set supply limits unilaterally.

In October 1973, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel. In response to a major U.S. aid program to support Israel, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries banned crude exports to the U.S.

From a market perspective, the embargo had only a short-term effect and did not change U.S. policy. But from a psychological perspective, the long lines for gasoline and spiking fuel prices had a huge impact. Suddenly, the most powerful nation on earth found itself extremely vulnerable. Energy security joined the lexicon and U.S. energy independence became the goal.

Geopolitical shift

The full OPEC cartel, however, is not a modern Standard Oil or RRC or Seven Sisters. It has never held the stranglehold on supply and price like previous crude power brokers because too many forces—geopolitical and economic—have been beyond its control.

One of them was the Shale Revolution, which not only slashed U.S. imports but thrust the country back into the realm of oil exporters. Another is the energy transition, in which net-zero carbon emission goals have led many oil customers in the industrialized world to favor renewable and other cleaner fuel sources over fossil fuels.

Major economic disruptions also factor in. The real estate bubble that burst in late 2008 tested the inelastic nature of gasoline demand. In fact, motorists showed that they would not buy as much fuel when their incomes decreased. The COVID-19 pandemic had the same effect. When the world shut down, the low price of gasoline was meaningless because there was nowhere to go.

If not an actual geopolitical sea change, there has, at least, been a perception of one. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter laid out what is known as the Carter Doctrine, in which he pledged U.S. military force to defend its interests in the Middle East, namely the flow of oil to the U.S. and western Europe.

Those interests were challenged in late 1990, when Iraq invaded Kuwait and took over the OPEC member’s oilfields. President George H.W. Bush responded by building a 38-nation coalition to oust the Iraqis.

Ostensibly, Operation Desert Storm was about defending an ally from aggression, but “we wouldn’t have defended Kuwait if Kuwait hadn’t been a big oil producer,” Finley said.

In 2019, however, the biggest oil producer of them all, Saudi Arabia, came under attack. Iran-backed Houthi rebels hit the Khurais and Abqaiq oil processing facilities, forcing the Saudis to suspend production of 5.7 MMbbl/d. While President Donald Trump offered U.S. support for Saudi self-defense, he didn’t offer U.S. forces.

“It was every energy security analyst’s worst nightmare,” Finley said. “And President Trump’s response was, ‘it’s not an attack on America. We don’t import that much oil from Saudi Arabia. Not our problem.’”

Finley disagrees. It still is a U.S. problem, he said, and noted that about 20% of the world’s oil traverses the Strait of Hormuz. The Navy’s Fifth Fleet remains based in Bahrain, where it patrols the Persian Gulf, Red Sea, Arabian Sea and parts of the Indian Ocean.

“It’s a global marketplace and oil is still the biggest fuel for the U.S. economy,” he said. “So, the United States is still vulnerable, even if we don’t import oil from Saudi Arabia. But I think the political reality was very clear and it was very clear to the Saudis, too.”

The more things change…

The world has changed in countless ways since John D. Rockefeller bought large tracts of oak timber in 1870 to produce his own 42-gallon barrels. The desire to control the price of oil, however, and the market’s refusal to cooperate, has not.

“I think we are going to see volatility in prices continue for the foreseeable future,” said Emma Richards, London-based associate director for oil and gas at BMI. “I don’t think that we are going to move away from the kind of cyclicality that has always characterized that industry.”

But the energy transition does introduce a twist: “I think, increasingly, those price swings will be policy led,” she said during an August webinar. “So, the nature of the cycles will change somewhat.”

What determines price in the energy transition really comes down to which progresses faster—policies that hold back supply or policies that curtail demand.

“We’re never going to find a perfect balance between those two things,” Richards said. “So, in periods where the supply is more heavily curtailed, we’ll see prices rise and vice versa when demand-side policies come more into effect.”

“Volatility is the name of the game,” Mike Blankenship, managing partner of Winston & Strawn’s Houston office and cohead of its energy and infrastructure industry group, told Hart Energy. “I do think that is changing, though, with the energy transition.”

KPMG’s Gildea believes the development of renewables and other non-fossil fuel sources could ultimately help to tame price volatility.

“There’s the potential that we could have some stability, more stability, in oil prices longer term as we have more options around different types of fuels,” she said. “Also, as we have more technology advances from energy storage and things like how we’re managing the grid system. That could potentially provide more stability from a price perspective.”

It won’t happen overnight, she said, but will evolve over the next 50 years. But will the energy transition impact prices in the short term?

“My reaction would be yes,” said Urszula Szalkowska, Poland-based managing director for Europe at EcoEngineers, a global consulting firm that works with companies to navigate the energy transition.

“Especially in Europe, where in road and aviation, there is a steep decarbonization through biofuels.

“My thinking is that this is going to impact demand for fossil fuels,” she told Hart Energy. “[Producers] will have to look for different markets, like chemicals, where decarbonization is expected through more efficient processes, which also adds to the price.”

The difficulty in predicting prices between now and 2050, when the world aspires to be net zero, stems from the difficulty in predicting anything over the next 27 years. The past teaches us that we often have no clue as to what the future holds.

In 1996, for example, the Shale Revolution was but a twinkle in George Mitchell’s eye.

“People didn’t know that cell phones were going to be the way we live,” Blankenship said. “And that people are going to become billionaires because of apps on cell phones.”

In his opinion, the technology that will drive oil and gas and the energy transition has not been invented or, at least, perfected yet.

Rockefeller may have figured out how to manage the price swings inherent in energy, but he couldn’t manage them forever. Neither could anyone else.

And if past is prologue, the markets of the future offer this certainty: they will be volatile.

Nothing Beats Light and Sweet

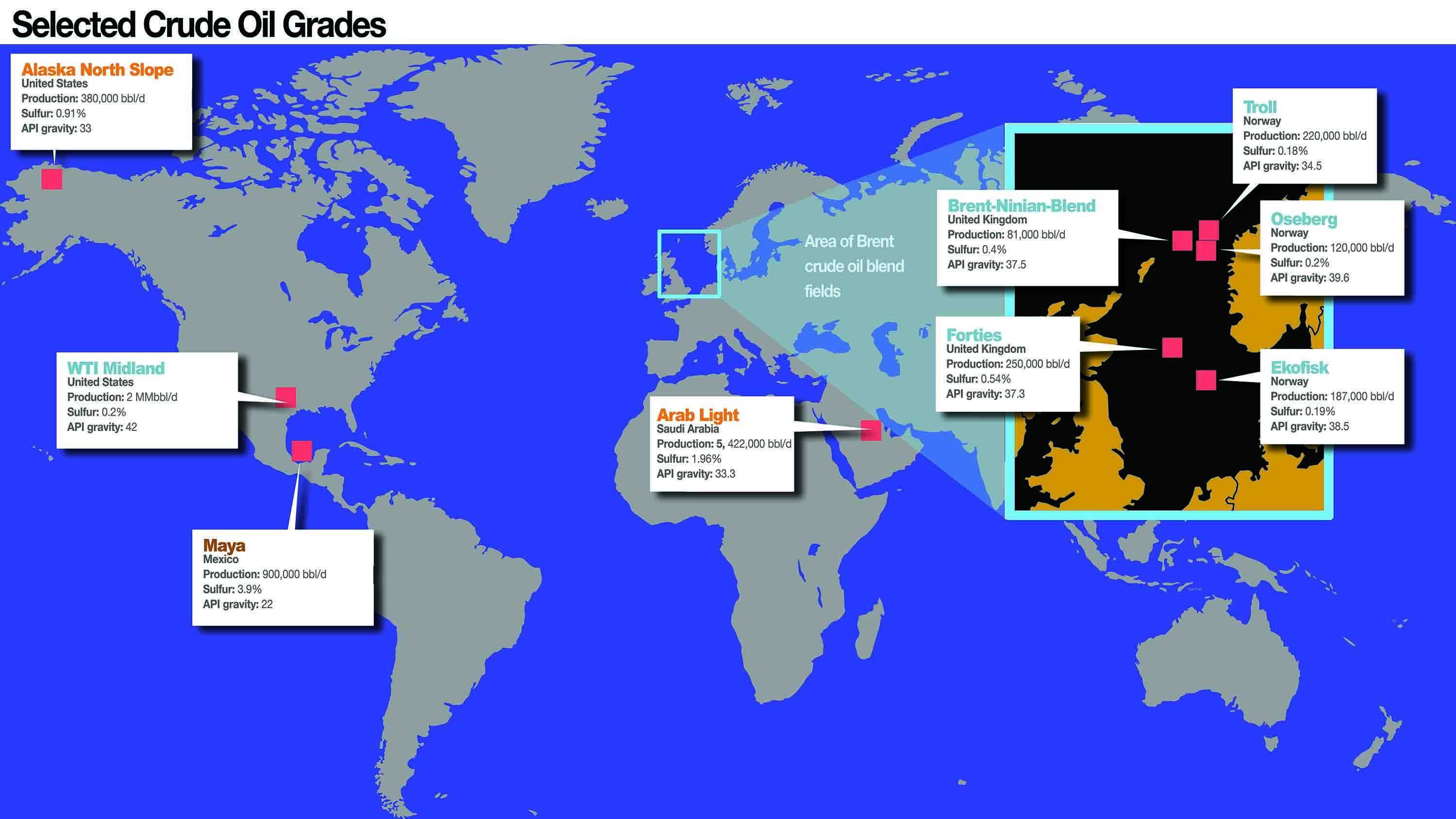

While the industry expression, “not all barrels are created equal” is true, it’s also true that if enough barrels are created in a way that is more or less the same, they can establish a benchmark price.

Two general criteria are typically used to set a benchmark. One is API gravity, which relates to viscosity, or how heavy or light a particular oil is compared to water. If an oil’s API gravity is greater than 10, it is lighter than water and will float. If less than 10, it is heavier and will sink. (Only one oil on Platts periodic table of oil, Sqepuri in Albania, is listed as less than 10.)

The other standard is sulfur content. Air quality regulations across the globe mandate that sulfur be removed in the refining process. The greater the presence of sulfur, the more expensive it will be to eliminate.

“When you bring a benchmark, you need to hit those specs in the blend,” Birol Dindoruk, professor of petroleum engineering, and chemical and biomolecular engineering at the University of Houston, told Hart Energy.

The international benchmark is a blend commonly referred to as Brent, but actually refers to production from five fields in the North Sea: Brent and Forties (UK) and Oseberg, Ekofisk and Troll (Norway). Output from the original Brent field is a small fraction of what it was and, in May, WTI Midland was added to the group to add muscle to a weakening brand.

But gravity and sulfur content are not the only metrics used to determine price.

“Your oil may have some metals in it that people don’t want,” Dindoruk said. “When you look at these benchmarks, they don’t cite it, but of course, the buyers know that from analysis. You may think that you are selling it as WTI but if you have some nasty stuff in it, the buyer is going to discount the price as well.”

So, not only are all barrels not created equal, they are not equal even within the U.S. benchmark WTI traded in Cushing, Oklahoma. The WTI grade that was added to the international Brent benchmark collective is restricted to a particular light, sweet crude extracted in fields near Midland, Texas, in the Permian Basin.

Recommended Reading

Production Begins at Shell’s GoM Whale Facility

2025-01-09 - Shell’s Whale floating production facility in the Gulf of Mexico has reached first oil less than eight years after the field’s discovery of 480 MMboe of estimated recoverable resources.

Analysts’ Oilfield Services Forecast: Muddling Through 2025

2025-01-21 - Industry analysts see flat spending and production affecting key OFS players in the year ahead.

Exxon Seeks Permit for its Eighth Oil, Gas Project in Guyana as Output Rises

2025-02-12 - A consortium led by Exxon Mobil has requested environmental permits from Guyana for its eighth project, the first that will generate gas not linked to oil production.

Analysis: Middle Three Forks Bench Holds Vast Untapped Oil Potential

2025-01-07 - Williston Basin operators have mostly landed laterals in the shallower upper Three Forks bench. But the deeper middle Three Forks contains hundreds of millions of barrels of oil yet to be recovered, North Dakota state researchers report.

E&P Highlights: Jan. 13, 2025

2025-01-13 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, including Chevron starting production from a platform in the Gulf of Mexico and several new products for pipelines.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.