Editor’s note: This is part of an ongoing series of Oil and Gas Investor articles examining major shale play trends— from electrification to M&A to infrastructure needs— as E&Ps enter 2025.

Energy Transfer (ET)’s new pipeline project is an encouraging sign for people keeping an eye on the gas market.

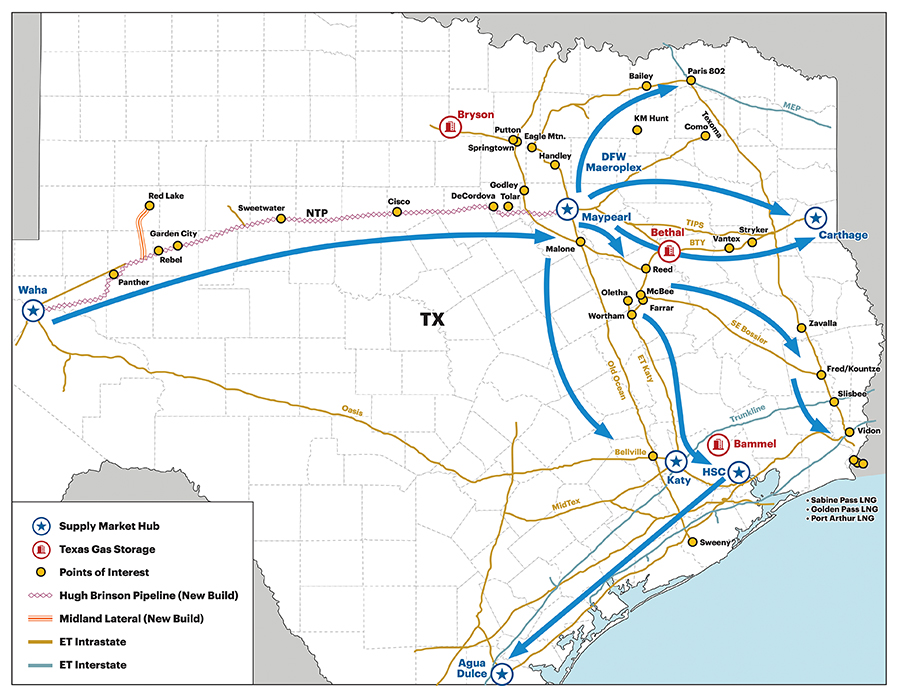

In early December, when the company announced the $2.7 billion Hugh Brinson Pipeline (formerly Warrior) had reached FID, ET signaled a potential market transformation.

The pipeline is being built in a Permian Basin, however, which had “solved” its egress problems after a couple of other pipeline projects were announced before Hugh Brinson, analysts said.

Building a pipeline where egress is not needed indicates that demand at the end of the line is driving production, which means that an oversupplied U.S. gas market could finally see the light at the end of a very low-priced tunnel.

The Permian

In 2023 and most of 2024, the primary problem in the Permian Basin and for producers nationwide has been too much natural gas in the system and not enough pipeline capacity to take it away.

Natural gas prices at the Waha Hub near Pecos, Texas, spent much of 2024 in negative territory. Associated gas-to-crude ratios continued to climb, and some E&Ps cut crude production as the only other option was paying the price for flaring.

The situation changed with the opening of the 2.5 Bcf/d Matterhorn Express Pipeline, which started operations at the beginning of October and delivers natural gas to the Katy, Texas, area near Houston. East Daley Analytics reported the new line ramped toward capacity faster than any other pipeline the firm had monitored before.

Before the Matterhorn had started flowing, the next natural gas pipeline slated for the Permian, the 2.5 Bcf/d Blackcomb, was announced by a JV led by WhiteWater Midstream. WhiteWater expects the line to be operational by the second half of 2026. Blackcomb will deliver to the Agua Dulce Hub near Corpus Christi in South Texas.

A few weeks later, Kinder Morgan announced it was moving forward on a 570 MMcf/d expansion of the Gulf Coast Express, a pipeline that also ships to South Texas ports.

Several analysts reported that the natural gas egress capacity problems for the Permian were solved, and that another pipeline would therefore not be needed for operators to ship all of the associated gas they produce.

Which was why Energy Transfer’s announcement that the company would build the Hugh Brinson pointed to growing demand for natural gas—a situation for which the U.S. gas market has been waiting, analysts said.

Unlike other recent pipeline projects, both built and planned, ET’s line does not head directly to the LNG and processing centers on the Gulf Coast. Instead, the line heads directly east from the Permian to North Texas.

“There is only one reason [Hugh Brinson] would still get built: demand pull from the DFW [Dallas/Fort Worth] area from data centers and electric utilities,” said Ajay Bakshani, director of analytics for East Daley Analytics.

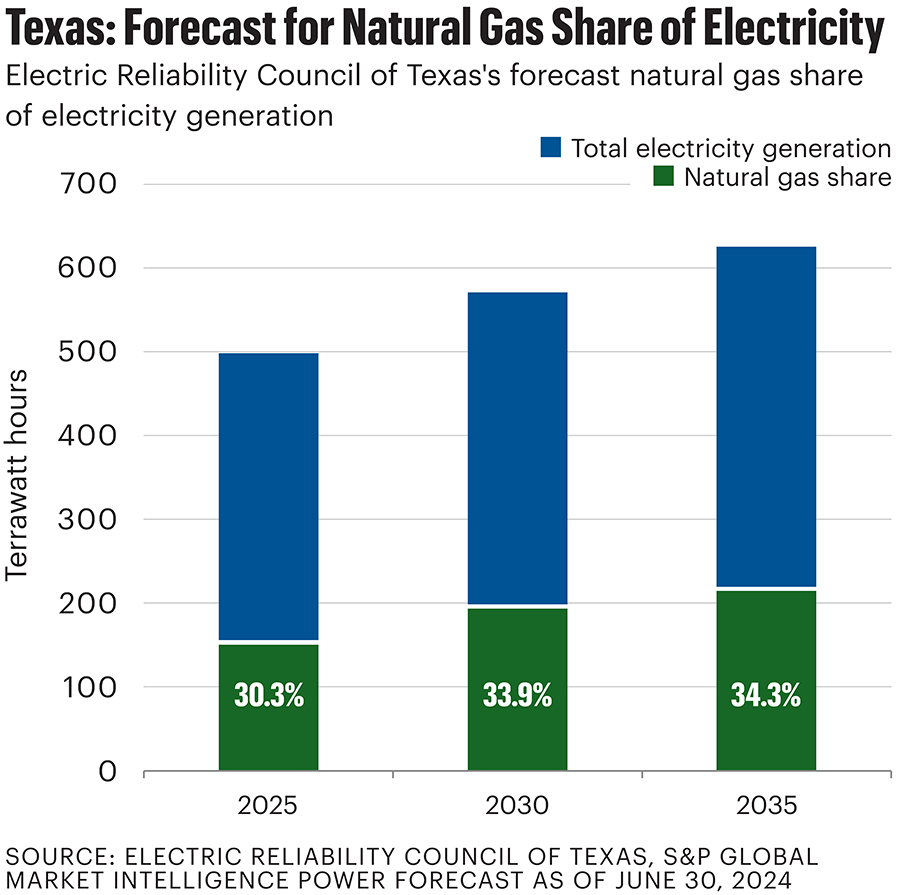

Midstream companies and gas producers spent much of 2024 discussing the upcoming increase in demand to keep up with a rapidly growing need for electricity in the U.S. market.

“In my decades of experience in the mid-term arena, I’ve never seen a macro environment so rich with opportunities for incremental build-out of natural gas infrastructure,” Rich Kinder, executive chairman at Kinder Morgan, said during his company’s third-quarter conference call.

Multiple executives at other midstream and gas production companies have said similar things, but the details of upcoming moves were not available.

The Hugh Brinson announcement provides a fairly good tell that electrical and data center demand is solidifying.

Dallas/Fort Worth has the second-highest concentration of data centers outside of Northern Virginia and ET’s management also hinted that growing demand drove the pipeline decision, saying the Hugh Brinson’s contracting is “weighted a little bit heavier towards market pull than it is on producer push” during its third-quarter earnings call.

“Unlike producers, demand-pull customers like electric utilities do not care about overbuilding the basin as much as securing supply,” Bakshani said. In two years, the natural gas egress out of the Permian could potentially be overbuilt.

However, at least one analyst said the usual production scenario could still be in play in the Permian, with Energy Transfer’s decision coming about because producers still want more natural gas egress.

“In general, natural gas pipelines only FID when they get customer commitments to build the pipeline,” said Hinds Howard of CBRE Investment Management.

“So, the takeaway from the [Hugh Brinson] FID is that producers are willing to commit to takeaway capacity because it is needed to avoid bottlenecks on the horizon.”

Howard said ET did call out that project’s advantageous position with power plants and data centers, but believes the bulk of the commitment for the pipeline came from producers pushing for more egress instead of the pull from downstream customers.

Analysts easily come to different conclusions about Texas production.

Gauging the activity levels of the Permian always takes some guesswork. Basin production numbers are a black box, thanks to the Permian being in the same state where most of its crude and natural gas are shipped for refining and processing. Pipelines do not have to register the amount of product they ship unless they cross state lines or international borders. Therefore, analysts for the Permian have to rely on secondary indicators to determine production numbers.

Appalachia

In the mid-Atlantic and Southeast, midstream power players have been building up their infrastructure to supply gas fired power systems. This year could find producers able to unlock a supply that’s been backed up thanks to antidevelopment sentiment that has held sway in the region.

“A tremendous amount of demand has been building up,” said Williams Cos. CEO Alan Armstrong during a broadcast interview on CNBC in November.

Large utilities are contracting with Williams now for future capacity, while new data centers developers are seeking on-site power generation. Before the end of 2024, the company signed a precedent agreement for expansion of the existing Dalton lateral line that serves northern Georgia. This expansion will support load growth from increased electric power generation driven by industrial reshoring and data center growth.

“We’re seeing people contacting us directly, wanting to get natural gas off of our big systems to fuel new power generation in what they call behind the meter,” Armstrong said. “So, rather than going through the utilities, they’re actually wanting to install their own ower generation and not have to deal with the long queues that exist in a lot of places right now to get connected to the grid.”

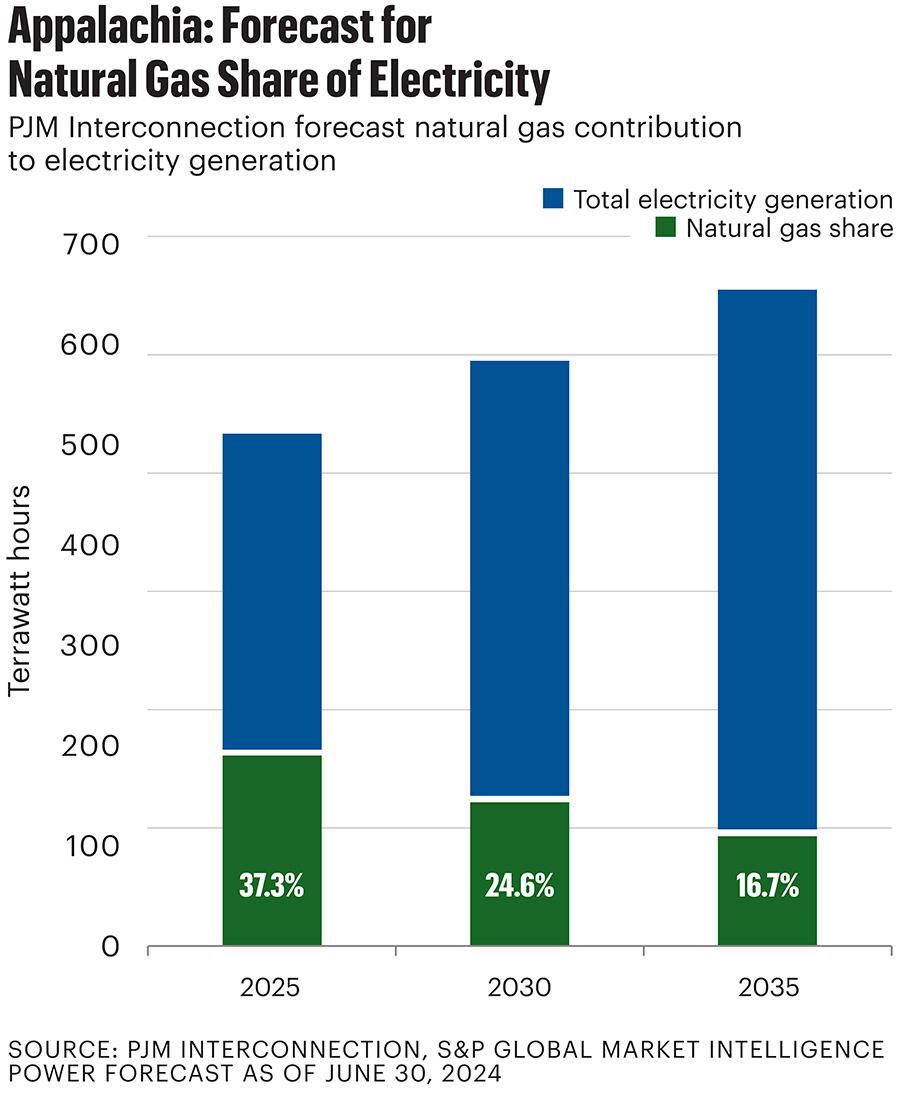

EQT’s CFO Jeremy Knop noted during his company’s third-quarter earnings call that much of the new demand is coming from the eastern U.S., thanks to concentration of data centers and the reshoring industrial movement.

“This demand will be regional, with more than half likely to come from the Southeast in the PJM markets,” Knop said. PJM Interconnection is the largest U.S. electrical grid operator and provides services to parts of 13 states, including Pennsylvania, Kentucky and West Virginia.

Knop forecast during the meeting that data centers, coupled with the ongoing retirement of coal plants in the region, could add up to 10 Bcf/d of natural gas demand by 2030.

Haynesville

Producers in the Haynesville Shale, located in northeastern Texas and northwest Louisiana, are also expecting to see a demand increase, but one driven primarily by the long-awaited opening of several LNG liquefication and export terminals along the Gulf Coast.

The region’s proximity to the heaviest concentration of LNG production in the U.S. will enable it to play a major role as several plants start to come online.

Venture Global’s Plaquemines LNG loaded its first cargo in mid-December. The plant will have an intake capacity of 2.6 Bcf/d once fully operational.

Expand Energy, the nation’s largest natural gas provider, put an emphasis on Haynesville development toward the end of 2024. In November, the company reported 12 rigs in operation, with eight in the Haynesville and four in the Appalachian Basin.

Uinta

One of the smaller basins in the U.S. may also have a major role in the industry’s future.

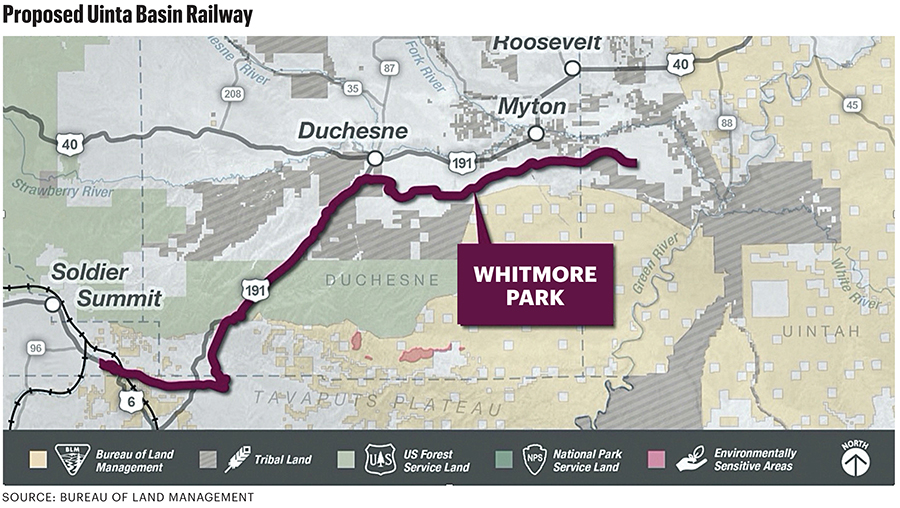

As 2024 drew to a close, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments in the Uinta Basin railway case.

Producers in the play have long tried to expand takeaway capacity for the basin’s waxy crude, which is so thick that it can only be shipped by rail.

A proposed new railway was stymied by a lawsuit by Eagle County, Colorado, and environmental group Center for Biological Diversity.

The railway builder lost the case on its appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. The panel ruled that to be approved, the railway project designers must consider not only the CO2 produced in the direct operation of the railway, but in the follow-on effects of delivering more crude to producers.

The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which heard arguments in early December.

Tom Sharp, director of permitting intelligence for analytical firm Arbo, said there was no clear signal of which way the court would turn. “The justices probed two competing approaches. Industry advocates pushed for a bright-line test based on ‘proximate cause,’ which is a concept borrowed from tort law that limits liability to reasonably direct harms, just as a negligent driver wouldn’t be liable if a delayed doctor’s patient died across town,” Sharp said in an email to Oil and Gas Investor.

“Along these lines, the industry counsel’s standard would be that agencies shouldn’t be faulted for not evaluating impacts that are both remote in time and place, when another agency has regulatory authority.”

Attorneys for the government argued, however, that strengthening federal agencies’ discretion “to determine ‘reasonable’ scope of the environment review could reduce litigation without creating regulatory gaps due to the extraordinary breadth of varied actions the government needs to analyze,” Sharp said.

The follow-on effects of adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere was a major issue for the LNG industry in 2024.

The D.C. appeals court vacated two federal permits for developing plants in Texas, saying that more consideration needed to be given to the total CO2 the projects would produce overall.

The Supreme Court is expected to release its decision in the spring.

Recommended Reading

Expand Lands 5.6-Miler in Appalachia in Five Days With One Bit Run

2025-03-11 - Expand Energy reported its Shannon Fields OHI #3H in northern West Virginia was drilled with just one bit run in some 30,000 ft.

Baker Hughes: US Drillers Add Oil, Gas Rigs for Third Week in a Row

2025-02-14 - U.S. energy firms added oil and natural gas rigs for a third week in a row for the first time since December 2023.

Blackstone Buys NatGas Plant in ‘Data Center Valley’ for $1B

2025-01-24 - Ares Management’s Potomac Energy Center, sited in Virginia near more than 130 data centers, is expected to see “significant further growth,” Blackstone Energy Transition Partners said.

Huddleston: Haynesville E&P Aethon Ready for LNG, AI and Even an IPO

2025-01-22 - Gordon Huddleston, president and partner of Aethon Energy, talks about well costs in the western Haynesville, prepping for LNG and AI power demand and the company’s readiness for an IPO— if the conditions are right.

Cummins, Liberty Energy to Deploy New Engine for Fracking Platform This Year

2025-01-29 - Liberty Energy Inc. and Cummins Inc. are deploying the natural gas large displacement engine developed in a partnership formed in 2024.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.