Former President Donald Trump met with a cadre of top oil and gas CEOs in April and reportedly proposed a deal: provide $1 billion for his campaign and he would fast-track federal permitting for energy projects, including drilling and LNG export terminals.

“Scandal!” the environmentalists shrieked. “It’s a quid pro quo!”

Not so. Unless he promised to advance specific projects in exchange for donations, there was no violation of campaign finance laws. It was a campaign promise, and not exactly a secret.

As the 2024 Republican Party platform states: “Republicans will increase energy production across the board, streamline permitting, and end market-distorting restrictions on oil, natural gas and coal.”

What Trump said, in effect, was that he needed funds to run his campaign, and if donors were to provide those funds, he would be in a better position to win and do what he already said he was going to do. Or, what every politician says while running for office, more or less.

What is omitted from the telling of this pearl-clutching episode is the underlying purpose of campaign contributions for the donor: access.

Want to share a chopped steak dinner at Mar-a-Lago with the former and possibly future president of the United States? It’ll cost in political contributions. A lot.

But is the spending on political donations and lobbying to gain access to Washington’s powerful people in the executive branch and in Congress a worthwhile investment? Oh, heck yeah, and it can be quantified.

“The average returns from lobbying expenditures are estimated to be over 130%,” wrote economist Karam Kang in an article about policy influence, specifically concerning the energy sector.

In her peer-reviewed paper, Kang, now at the University of Wisconsin, analyzed how lobbying on behalf of the energy industry influenced energy policy that resulted in financial benefit to the industry.

Jack Belcher, principal at Cornerstone Government Affairs, was not surprised.

“Money makes a difference,” he told Oil and Gas Investor. “It makes a difference in getting your voice heard.”

Belcher’s job is to influence lawmakers, and he finds it a lot easier if his clients are willing to engage in the political process and make campaign donations, particularly through corporate political action committees (PACs), where the sky is the limit in terms of how much can be spent.

“That’s not to say you’re not going to get your voice heard if you don’t spend money,” he said. “I’ve got clients that don’t. We still get what we need done. But it helps.”

How it works

To be heard, it’s not necessary for a special interest group like oil and gas to carpet bomb Capitol Hill with cash. A little selectivity can go a long way.

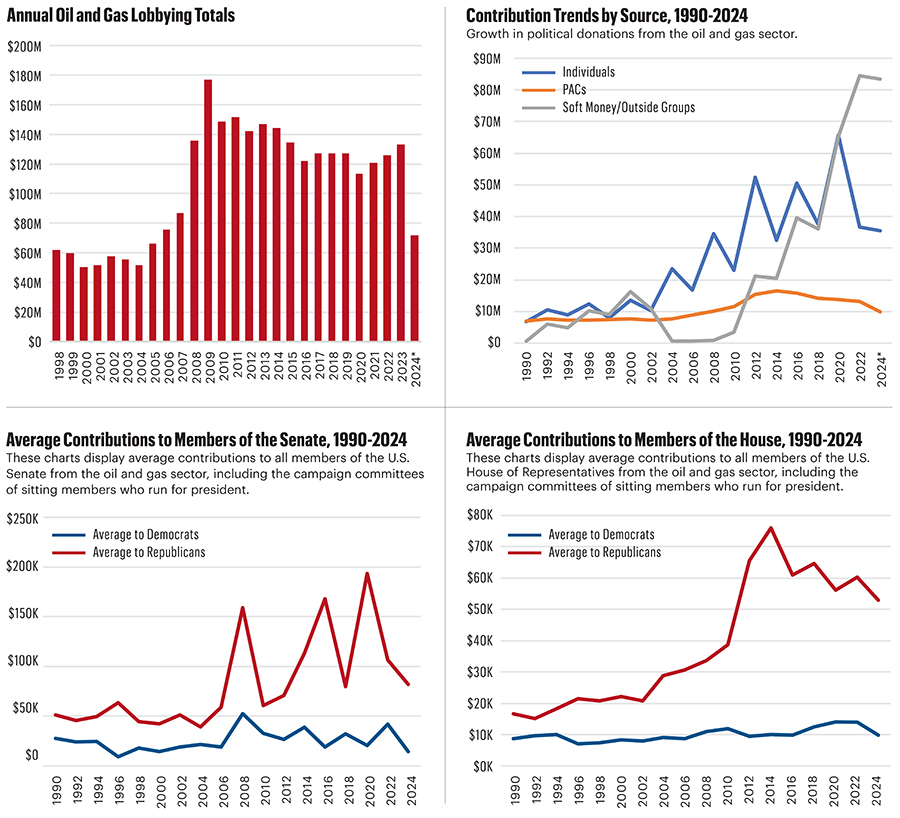

As a sector, energy and natural resources trails most in political donations, according to OpenSecrets, a nonpartisan research group that tracks money in U.S. politics. As of the end of July, the finance/insurance/real estate, health, communications/electronics and lawyer and lobbyist sectors spent more.

The industry, with donations totaling $182 million as of July 29 in the 2023-2024 election cycle, ranked ahead of the labor, transportation, agribusiness, construction and defense sectors.

What a company or industry group needs to decide, Belcher said, is what it wants to accomplish. Is it gaining tax breaks? Fending off regulations? Disposing of the Jones Act? Lobbyists can help determine who to target and how to target them.

An E&P, for example, benefits most from influencing lawmakers who sit on the Natural Resources Committees of both the House of Representatives and the Senate, along with the House Energy and Commerce Committee and Senate Environment and Public Works Committee.

A company that operates globally will pay attention to members of House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations. If taxes are the concern, then it might be necessary to seek out a champion on House Ways and Means or Senate Finance.

But influencing legislation is not the only goal of political spending. Issues pop up that are not even anticipated during election campaigns.

One example was the Biden administration’s freeze on approvals for LNG export applications, which took effect in January. Oil and gas lobbyists immediately reached out to the powers that be on Capitol Hill, and the powers that be took their calls. Again, money equals access.

In April, a subcommittee of the House Oversight and Accountability Committee held a hearing to examine the political nature of the permitting pause. It may not have accomplished much more than putting a Department of Energy official on the hot seat, but it demonstrated that allies in the House were responsive to industry concerns.

In fact, the pause was reversed in July by a federal judge’s ruling in a lawsuit brought by 16 state attorneys general. The reversal turned out to be an example of influence at the state level, rather than the federal.

Not left out

Decisionmakers in the oil and gas industry are well known for favoring Republican lawmakers in Washington. As of the end of August, 75% of energy industry donations went to Republicans, according to OpenSecrets. But sticking with one party over the other isn’t the best strategy, Belcher said.

“If you’re an oil and gas company, you’re trying to find those Democrats that are somewhat reasonable on oil and gas,” he said. “You try to find the candidates that are good on their issues; you want to have a go-to in both parties.”

That’s not always easy for oil and gas lobbyists. Ideally, he said, there would be more of a balance in donations to lawmakers of the two major parties, but many Democrats have refused contributions from fossil fuel companies.

“They don’t even want to take the money, or they’re just not going to be supportive of your position,” Belcher said. In that case, he sometimes recommends sending money to certain members of Congress anyway, just to remind them that people employed in the industry live in their districts.

Not all Democratic representatives are averse to industry funds. Among those who have accepted donations from industry PACs in the past are Texas Reps. Henry Cuellar, Lizzie Fletcher and the late Sheila Jackson Lee, and South Carolina Rep. James Clyburn, the former House majority whip.

The political polarization of the country is to blame. In this with-us-or-against-us era, it has become untenable for many Democrats to be in contact with the oil and gas industry lest factions in their party disown them. Same for Republicans with the renewable energy sector. Critical issues like energy security and climate change have become so politically charged that progress on solutions is agonizing at best.

The value of speaking up

But even if money talks, it’s no substitute for the donor actually saying the words. There are those who choose not to speak, in which case, their voices are rarely heard in the corridors of power.

“Companies are really weird this way,” Belcher said. “Some companies have a cultural aversion to all of this, especially European companies.”

And then there’s Harold Hamm.

“You’ll have companies that are … willing to take a lead on an issue that maybe is a lot bigger than themselves,” he said, referring to the executive chairman of Continental Resources. “You see that happen a lot.”

![“We’d go office to office and office, and [Harold Hamm was] tireless out there,” Belcher said. “They loved him. You’ve got people like that who just get passionate about things and play this kind of role.” —Jack Belcher, principal, Cornerstone Government Affairs](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Harold%20Hamm_1.jpg)

Hamm, who heads the nation’s top-producing private E&P, was among those who lobbied ferociously to lift the crude oil export ban, an effort that resulted in its repeal as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act that was signed into law by President Barack Obama in December 2015. But Belcher witnessed Hamm’s political savvy firsthand during his time at IPAA, when he would escort Hamm around Capitol Hill. In that period, the Continental portfolio included operations on federal land.

“We’d go office to office and office, and [Hamm was] tireless out there,” Belcher said. “They loved him. You’ve got people like that that just get passionate about things and play this kind of role.”

Like oil and gas, politics is a relationship business. Most politicians are, by their nature, extroverts. They need money and votes to keep their jobs, but they thrive on interpersonal connections and attention, too, especially with those who are also in positions of power. When captains of industry come to town, they perk up.

Trump could have just as easily made his fundraising pitch via Zoom. By gathering the executives for dinner, he made it personal (not to mention giving himself the homefield advantage). The executives benefit from the connection, as well.

“When I think about all of these big, consequential pieces of legislation that get passed, it isn’t just the organizations,” Belcher said. “It’s the individuals that actually go out there and champion something and help make it happen.”

Few industries are regulated to the degree experienced by the oil and gas industry. Not engaging in the political process via campaign donations and lobbying can deny companies and executives access to those who make impactful decisions, and it can limit input when legislation is proposed and debated.

It’s not just the return on investment due to the results of particular legislation.

“The total amount of lobbying expenditures is relatively small when compared to the value of the government policies they are intended to influence,” the economist Kang wrote in her paper, noting that “the content of a bill can and often does change throughout the entirety of the legislative process.”

That’s why influencing policy is more important than trying to alter the direction of a particular bill. It comes down to making a call to a powerful person in Washington and having that person pick up.

That kind of access costs. But it’s worth it.

Recommended Reading

BlackRock’s Fink Calls for Reliable US Power Grid—Now

2025-03-31 - “That starts with fixing the slow, broken permitting processes in the U.S. and Europe,” Larry Fink, the co-founder, chairman and CEO of $12 trillion investment-management firm BlackRock Inc., told shareholders March 31.

E&P Highlights: March 31, 2025

2025-03-31 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, from a big CNOOC discovery in the South China Sea to Shell’s development offshore Brazil.

US Drillers Cut Oil, Gas Rigs for First Time in Three Weeks

2025-03-28 - The oil and gas rig count fell by one to 592 in the week to March 28.

BP Earns Approval to Redevelop Oil Fields in Northern Iraq

2025-03-27 - The agreement with Iraq’s government is for an initial phase that includes oil and gas production of more than 3 Bboe, BP stated.

DNO ‘Hot Streak’ Continues with North Sea Discovery

2025-03-26 - DNO ASA has made 10 discoveries since 2021 in the Troll-Gjøa exploration and development area.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.