Capturing and burying a troublesome greenhouse gas deep underground is considered to be a solution for lowering emissions. But carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) must overcome some obstacles, experts say, as companies push to commercially scale technologies to bring down costs and U.S. regulators entice developers with tax incentives.

One impediment at this stage for CCS in the U.S. is the combination of regulatory hurdles, particularly for Class VI well injection, and development hurdles, such as navigating front-end engineering development, according to Rohan Dighe, analyst for Wood Mackenzie.

“Companies are really having to decide if they’re going to move forward with projects, how they’re going to execute them, when they’re going to execute them,” Dighe told Oil and Gas Investor. “We’ve seen a lot of companies move from early development to advanced development. But now what we’re seeing is companies are actually having to put money forward and move forward with FID…. We’re moving past the announcement phase more into an execution phase.”

Time will tell how many projects progress.

CCS is unfolding at varied rates in the U.S. and abroad amid global ambitions to cap global warming to about 1.5 C. The suite of technologies is seen as essential to helping hit the target. While progress is evident on some fronts, more action may be needed when it comes to infrastructure and economics to make projects a reality.

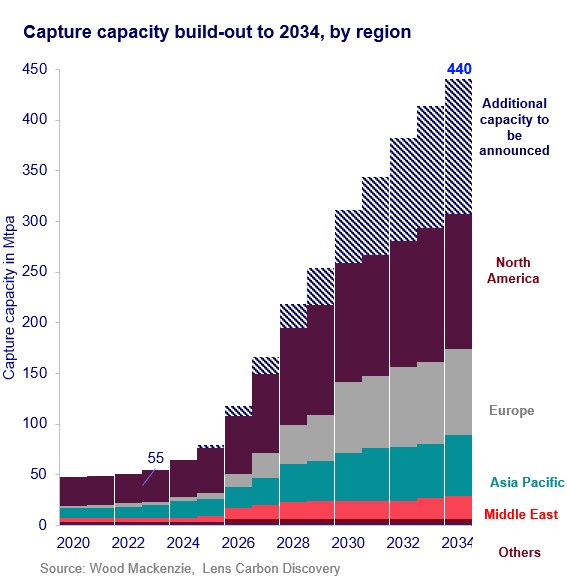

Currently, there is about 25.7 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) of capture capacity in the U.S. compared to about 56 mtpa globally, according to Wood Mackenzie. Ten years from now, the consultancy estimates there will be 125 mtpa of capture capacity in the in the U.S. and 448 mtpa globally.

Incentivizing action

Getting to that goal will require large investments: about $196 billion in total. About half of the investment needed is associated with carbon capture, with $53 billion for transport and $43 billion for storage. Most of the investment is expected to come from Europe and the U.S., where the 45Q tax credit is incentivizing CCS projects and bolstering the business case.

The U.S. 45Q tax credit offers $60/ton for storage associated with enhanced oil recovery (EOR); $85/ton for dedicated geologic storage; $130/ton for direct air capture with carbon utilization; and up to $180/ton for direct air capture with carbon storage.

But that likely will not be enough when it comes to deploying CCS for industrial applications such as steel production, cement production and petrochemical refining.

“The 45Q credit is not sufficient alone to justify deployment of CCS,” Dighe said. “So, these companies need to find other ways to monetize the CO2 captured. That could be in the form of premiums for things like steel, if they’re able to sell decarbonized steel at a higher price or if they’re willing to sell those credits. Or, if the company has internal carbon abatement targets they’ve set for themselves, there might be value there.”

At this point, without a clear idea of how much premiums could be, some companies do not have the economic incentive to move projects forward, he said.

On regulations, Louisiana, North Dakota and Wyoming have gained primacy over wells built to sequester CO2, putting the states in charge of permitting and enforcement responsibility instead of the federal government. Hoping to speed up the process, others states have lined up to follow suit.

“We’re waiting to see how long the life cycle is going to be for state-issued Class VI well permits,” Dighe said. “We’re not entirely sure, but it’s certainly going to be shorter than the EPA issued Class VI well permits, which take a particularly long amount of time.”

Leading on the Gulf

In Louisiana, legislators have been taking bold steps to strengthen CCS.

“You’re definitely starting to see an uptick in the development,” said Colleen Jarrott, a Louisiana-based energy attorney and partner with Hinshaw & Culbertson. “In Louisiana, we have about 55 projects that are pending.”

RELATED

Louisiana ‘Ready to Roll’ After EPA Grants Authority Over CCS Wells

Many of the projects sprung up following the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act, she said, but Louisiana regulators have enacted rules to enhance these projects. Six made it through bipartisan politics and got the governor’s signature. The new laws, which took effect Aug. 1, include one that gives pipeline companies authority to expropriate property rights for pipelines transporting CO2 for CCS projects and another that authorizes unitization for CO2 sequestration.

“If one landowner is holding out, that won’t totally sink the entire project. As long as you’re able to show that you have 75% agreement of the other landowners, you’re able to use a unitization process and go to the commissioner of conservation and get a certificate of unitization,” Jarrott said. “You will be able to then use that for pore space.”

Jarrott does not see anything on the legislative side in Louisiana that would hinder the state’s ability to scale up CCS, though some issues could arise before the next session rolls around. Like others, she pointed out that the projects are still expensive—which may limit the participation of smaller companies.

Then, there’s the matter of infrastructure.

Dominating infrastructure

The Gulf Coast has dominated CCS activity in the U.S. because of its abundance of existing CO2 pipelines and infrastructure. Other areas are not as fortunate. Massive amounts of infrastructure will be needed to move CO2 from capture locations to sequestration sites.

Citing studies conducted by the Great Plains Institute and U.S. Department of Energy (DOE), the Global CCS Institute said the “current CO2 pipeline transportation network in the U.S. must increase by four to 18 times its current size by 2050 to reach our climate goals.”

Current incentives are insufficient for some pipeline companies to let new projects proceed, Dighe said. It may make more sense from a capex perspective to convert existing pipelines, he said, though he cautioned that involves considerable work.

“Transport capacity is a risk because people don’t want to build a pipeline if there’s no capture, but then no one’s going to build transport,” he said. “Capture becomes expensive and then it becomes a cycle of people not doing stuff. So, it’s like everyone’s trying to see who blinks first.”

RELATED

As Uncertainty Lingers, CCUS Caught in a Catch-22 for Now

Companies with money, technical know-how and access to infrastructure, however, are strategically moving forward.

The hub approach

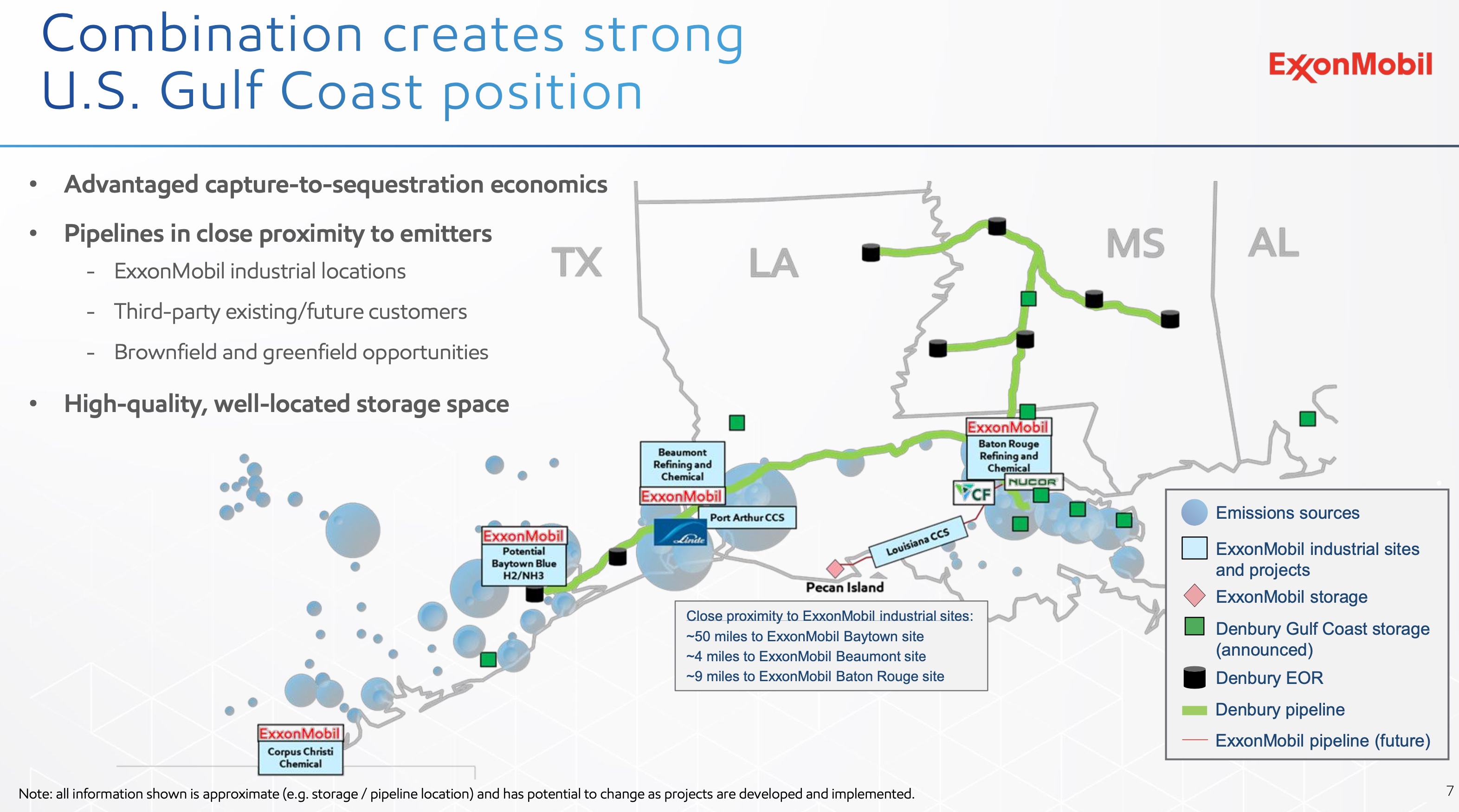

Texas-based Exxon Mobil is among the companies advancing ambitious plans to build out a CCS network. The company became the owner of the nation’s largest carbon pipeline network in 2023 when it acquired Denbury in a transaction valued at $4.9 billion. The deal added more than 1,300 miles of pipeline mostly in Louisiana, Texas and Mississippi and 10 onshore sequestrations sites, helping to pave the path toward a potential estimated 100 mtpa of CO2 emissions reduction.

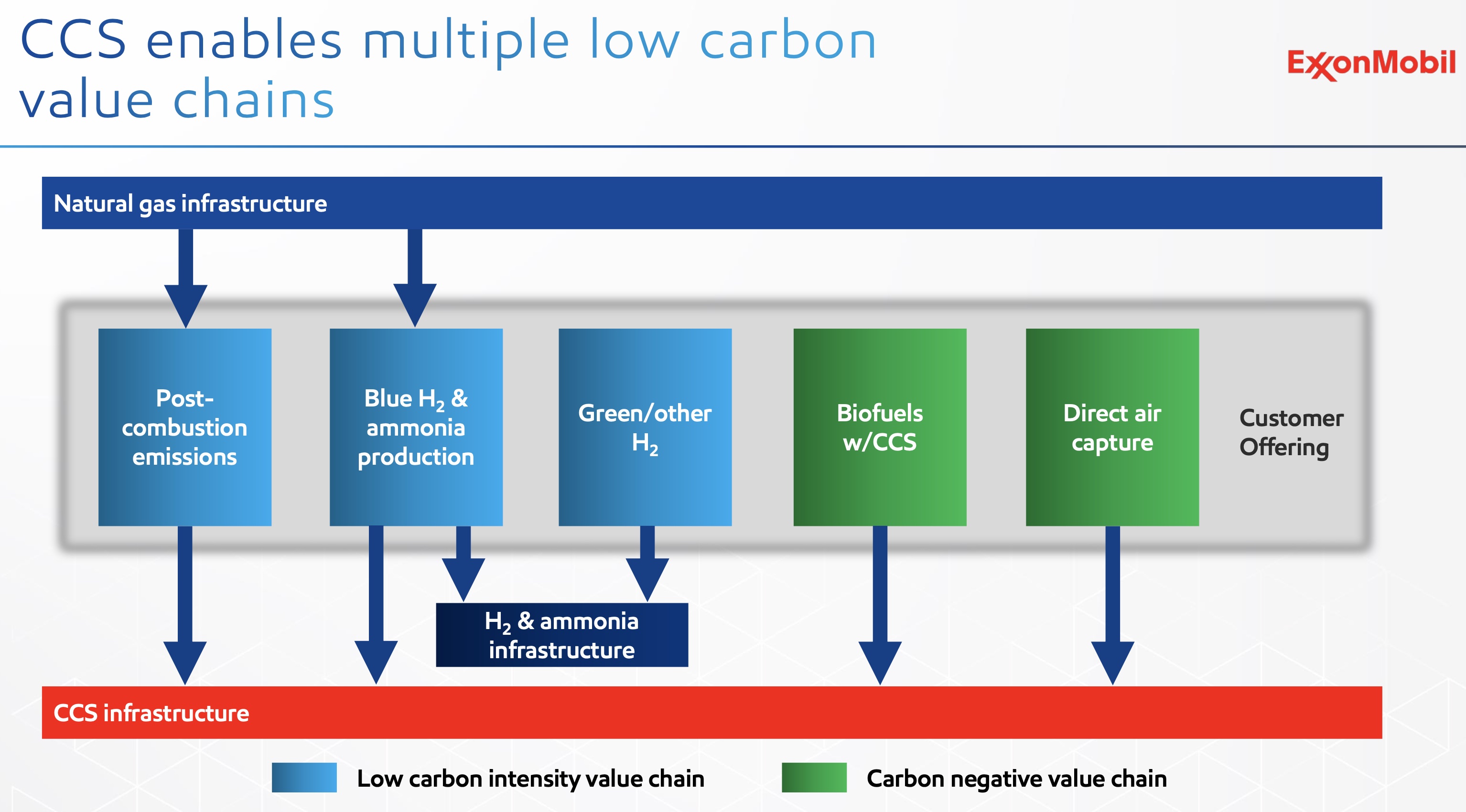

Now, with access to more than 15 onshore storage sites and more than 1,700 miles of CO2 pipeline, plus natural gas infrastructure, CCS customers on contract and access to large industrial emitters along the U.S. Gulf Coast, Exxon Mobil is driving CCS growth.

In Baytown, Texas, Exxon is developing a low-carbon intensity hydrogen plant, using natural gas as feedstock alongside carbon capture. The company plans to produce up to 1 Bcf/d of hydrogen while capturing more than 98% of the CO2 for storage underground. The CCS piece of the project would be among the world’s largest, storing up to 10 million metric tons (mt) of CO2 per year—equal to the emissions from more than 2 million cars.

This CCS project is part of the Houston carbon capture hub that has brought together roughly a dozen companies to reduce industrial CO2 emissions. Exxon has lined up definitive agreements with customers from three industries: Linde, industrial gases; CF Industries, fertilizer manufacturing; and Nucor Corp., steel.

“These are actual projects in motion. The definitive agreements, the civil works, are either done or progressing well,” Carl Fortin, global business manager of carbon capture and storage for the supermajor, said during an energy conference in Houston. “The first one of these projects will roll out next year. So, CCS is alive and happening. … It’s not all just talk.”

One-stop shop

Putting its CANSOLV CO2 technology to work capturing CO2 post-combustion, Shell is betting big on CCS. In addition to licensing its technology, the company has three operating CCS sites and about a dozen CCS projects in development globally, according to the company’s website.

However, “fast forwarding to this year. You can see that our pipeline of projects, our active projects have doubled. We’ve doubled our reference list,” Alexis Griffin, decarbonization technology licensing director for Shell, said during the energy conference. She referred to projects in play implementing Shell’s CANSOLV technology.

Shell teamed up with TechnipEnergies to serve as a one-stop shop to deliver CCS projects from concept to completion, said Venki Desai, commercial director for Technip. Shell provides the technology, and Technip serves as the EPC provider.

“What we have is a commercially proven, robust technology. We have high loading efficiencies, even at lower concentrations at 3-4% in flue gas. We can achieve up to 95% capture. And as you go higher into 8-10% concentration, then we can go all the way up to 99%,” Desai said. “So, from our experience on having operated these units over several years now and also working closely with our experts and Shell’s experts, we have been able to improve the technology in terms of emissions, lower degradation rates and lower energy consumption when compared to what it was 10 years ago.”

In June, Shell took final investment decisions (FID) on the Polaris carbon capture project at its Scotford refinery and chemicals complex in Alberta, Canada, and the Atlas Carbon Storage Hub with partner ATCO EnPower. Both projects are expected to start operations near the end of 2028.

Hopes are to see FID for the Calpine CCS project in Baytown by first-quarter 2025. The project, which was in the FEED phase in June, is designed to capture 95% of the CO2 emitted from Calpine Energy’s 830-MW gas-fired power station, using Shell’s CANSOLV solvent to capture more tha 2.2 million metric tons (MMmt) of CO2 annually. The captured CO2 will be transported and sequestered in a saline storage site on the Gulf Coast.

The project would be the first full-scale implementation of CCS technology at a natural gas combined cycle power plant in the U.S., according to the DOE, which awarded the project funding.

Eyeing economics

As companies move into FEED with government support, Dighe said some are going through different engineering providers to better understand costs, how various technologies compare and how costs can be lowered from a capture perspective.

“CCS technology in general is at this kind of point in its life cycle where it’s both relatively well understood, but also there’s these new technologies for carbon capture that that are not as well understood,” he said. “We don’t really know what they’re going to cost. We don’t know how they’re going to be executed at scale. They promise to reduce a lot of the costs of legacy CCS technologies.”

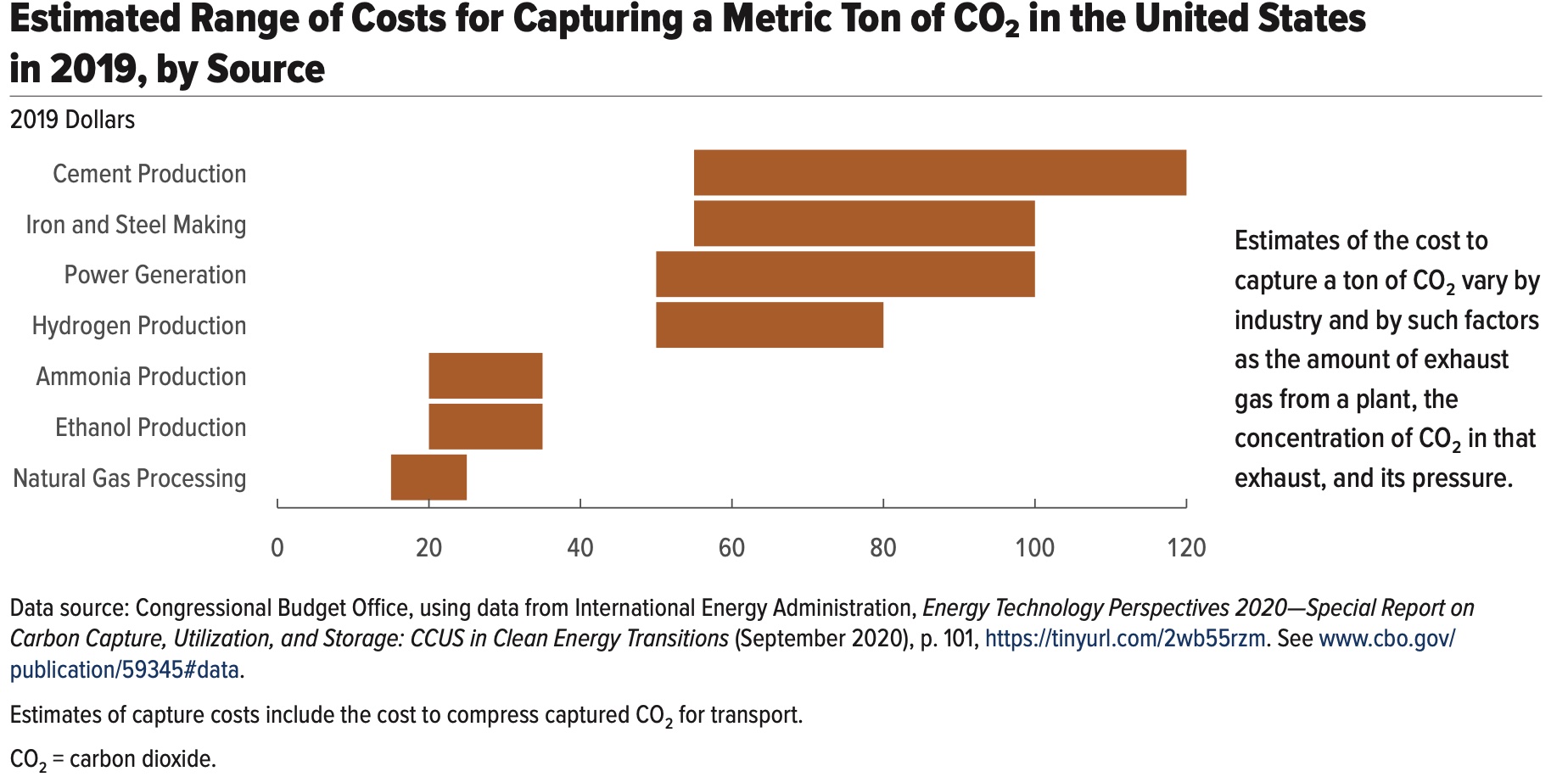

Estimates from the International Energy Agency show CO2 capture is roughly $15/mt to $35/mt (in 2019 dollars) in natural gas processing and ammonia and ethanol production, according to a 2023 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report on CCS. Capture costs are about $50/mt to $120/mt in power generation and other industrial processes such as the production of cement, iron, steel, or hydrogen.

Factors affecting costs include the concentration or purity of CO2 captured, but storage is also a concern.

“It hasn’t really been done at scale yet,” Dighe said.

“The revenue side is more complicated because it’s a market problem…. The market needs to be willing to pay for decarbonized goods in order to… overcome the cost difference between 45Q and the actual capture costs.”

According to Dighe, global markets with consumers willing to pay premiums for green cement or green steel do not exist, so reliance today is on government mandates.

“To alleviate some of those issues, some companies are trying really hard to focus on getting offtake agreements in places like Europe where you have regulatory environments that require decarbonized goods,” Dighe said.

Utilization has a role to play, as well.

Main ingredient

Today, CO2 is mainly used in fertilizer production and EOR, but tech companies have expanded the possibilities.

U.S. Steel signed an agreement this year to capture and mineralize up to 50,000 metric tons of CO2 annually using CarbonFree’s SkyCycle technology. CarbonFree’s technology converts CO2 into a version of calcium carbonate that can be used to make paper, plastics, personal care products, paint and building products.

Biotechnology companies are using CO2 to make fertilizer, fuel, food proteins and other applications. It could also be used to produce e-fuels when combined with hydrogen.

“That is a really expensive technology because you need green hydrogen along with it. And so, that becomes less likely to alleviate these concerns about high cost of capture right now in the near term,” Dighe said.

There are about 15 CCS sites operating in the U.S., according to the CBO report. Combined, the facilities have the capacity to capture 0.4% of total annual CO2 emissions. That percentage could increase to 3% if the more than 120 facilities are under construction or in development are completed.

“Those percentages are small, in part, because CCS is generally used in sectors that have the lowest costs for capturing CO2—such as natural gas processing and ammonia and ethanol production—and those sectors account for a small share of total U.S. CO2 emissions,” the report states. “Almost all CCS facilities recoup some of their costs by using the captured CO2 to force more oil out of partially depleted oil wells.”

Recommended Reading

2025 Hamm Summit Goal: Make US NatGas ‘Hero’ for Powergen

2025-04-11 - Stepping up power for data centers “is a phenomenal opportunity here that our industry has to take advantage of. We have to get this right,” the Hamm Institute for American Energy’s executive director Ann Bluntzer Pullin said.

Trio Petroleum Deal Marks Entry into Canada’s Heavy Oil Region

2025-04-10 - California’s Trio Petroleum will acquire producing wells in the Lloydminster, Saskatchewan heavy oil region in a deal valued at roughly $1.38 million.

Prairie Operating Hedged D-J Production Ahead of Market Downturn

2025-04-10 - Approximately 85% of Prairie’s remaining 2025 daily production is locked in at $68.27/bbl WTI and $4.28/MMBtu Henry Hub as part of a strategic hedging program, the company said.

EIA: Tariff Chaos, OPEC Output Increases Spell $57/bbl WTI in 2026

2025-04-10 - Energy Information Administration price estimates for 2025 and 2026 are bad news for producers—if they come to pass—as breakeven prices for operators, even in the Permian Basin, require between $61/bbl and $62/bbl to remain profitable.

Oil Falls More Than 4% as Investors Reassess Trump's Tariff Flip

2025-04-10 - Oil prices fell by nearly $3/ bbl on April 10, wiping out the prior session's rally, as investors reassessed the details of a planned pause in sweeping U.S. tariffs and focus shifted to a deepening trade war between Washington and Beijing.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.