Carbon capture and storage facilities capture CO2 emissions from industrial processes and power plants for underground storage, helping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. (Source: Shutterstock)

Economics, financing complexity, uncertainty and other challenges are putting carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) projects at risk despite the desire to get projects off the ground and across the finish line, experts say.

Potential pathways to revenue, however, could open new opportunities for companies and the investors backing them, according to a panel of executives from Kimmeridge, Bracewell, Enerflex and Exxon Mobil Low Carbon Solutions who gathered recently at a Wood Mackenzie conference to discuss funding CCUS projects.

Today, frequently “the base case doesn’t even work,” said Olivia Woodruff, director of decarbonization at private equity firm Kimmeridge. The firm uses a screening rubric to assess projects, but few can produce all the necessary components. “It’s very tough to invest dollars if you don’t have a binding contract; if you don’t have the value chain connected; if you’re in an area that has regulatory risk. The list can go on. When you go back to put pen to paper, the most optimistic case maybe barely skirts by.”

The U.S. and other parts of the world are counting on CCUS to help lower greenhouse-gas emissions. While the environmental benefits may be obvious to many, investors’ line of sight to revenue is blurry as developers contend with lengthy permitting wait times, some public opposition, securing offtake and transportation agreements and project economics.

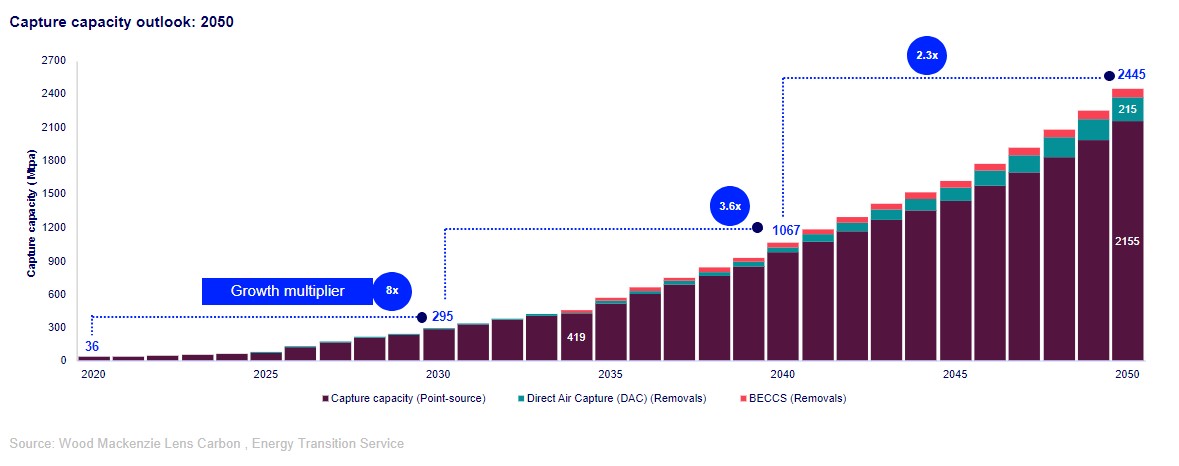

Still, analysts see potential for market growth. Wood Mackenzie forecasts capture capacity rising to 2,450 million tons per annum (mtpa) by 2050, up from an expected 295 mtpa by 2030—and a large increase from 2020’s 36 mtpa.

Some projects are challenged under current market conditions, said energy consultancy WoodMac, which is tracking about 1,200 projects.

CCUS uncertainty abounds

The biggest challenge to sanctioning projects is the lack of compelling economic returns for a given risk, according to Peter Findlay, CCUS economics and North America lead for Wood Mackenzie. Potential revenue could come from a variety of sources, he said:

- Carbon pricing;

- Government support such as grants or tax credits for capex or opex;

- A commercial price for CO2; or

- Product premiums and carbon offsets created or sold in voluntary carbon markets.

Kimmeridge sees cost uncertainty compounding, Woodruff said, adding “what gets more projects across line is seeing more projects getting across the line. … It’s tough, and I really do feel for these private developers out there trying to do something good. But, you know, it’s a Goldilocks situation.”

Many companies looking for capital for CCUS projects are in the pre-final investment decision (FID) stage, she said. “They’re maybe plus or minus 100% on their cost estimates. That’s a scary place to try to raise capital, especially when you’re asking for a $100 million check.”

Trying to determine whether a complex project with complex networks will qualify for 45Q tax credits adds to the uncertainty, according to Elizabeth McGinley, partner, tax department chair and energy transition practice chair for Bracewell.

“The guidance on 45Q is far more robust than it is for all of the other IRA [Inflation Reduction Act] credits, because remember, it wasn’t created by the IRA; it was created back in 2008, enhanced in 2018. So, it’s been around for a while. … There’s administrative guidance on it, but it doesn’t answer every question,” McGinley said. “So, people are trying to build projects with less than perfect information on credit qualification.”

The 45Q tax credit for carbon capture was raised to a maximum of $85 per ton for dedicated geologic storage and $180 per ton for direct air capture with carbon storage. The credit was created in 2008, enhanced in 2018 and updated in the IRA.

Complexity around financing such projects is another concern McGinley shared.

“How do you how do you finance them? What does it look like for tax equity? Does tax equity make sense in pre-combustion projects, or does it only makes sense in post-combustion projects where we have a lot more depreciation potentially to monetize?” she asked. “What about using the credits yourself, doing a combination of tax equity investment and transferability and direct pay?”

There’s more: “What is the timing for direct pay and how do we get parties offering financing comfortable with the uncertainty and timing of direct pay payments and then also the interaction between private financing and DOE [Department of Energy] loans in the space, subordination issues, structural issues. … [There are] a lot of challenges out there. Hopefully, the election is not one of them,” McGinley said.

Getting off the ground

For Joe Colletti, a U.S. Gulf Coast CCUS venture executive for Exxon Mobil Low Carbon Solutions, getting the timing right on various aspects of a project is a concern.

“Everything’s there to deliver carbon capture, to decarbonize existing facilities, reduce the carbon intensity of products. But the timeline still seems unknown,” he said.

The timing could involve permitting, policy and when others will move forward.

“Some of our more recent hurdles, not on execution side [but] on how we are building the business up, is how lukewarm some folks are. And when they get excited to want to move forward on an opportunity but then maybe hold because they start thinking about policy risk or what happens with this election cycle,” he said.

However, the energy giant is developing a CCS project as part of its planned low-carbon hydrogen plant in Baytown, Texas. It will store up to 10 million metric tons (mt) of CO2 per year—equal to the emissions from more than 2 million cars.

Exxon, which strengthened its CCS business with its acquisition of Denbury, has more than 6.7 million tons of CO2 under definitive agreements where it’s either the capturer, transporter and/or storage provider, according to Colletti.

RELATED

Exxon Adds 270,000 Acres for Largest Carbon Storage Site in the US

Findlay earlier pointed out that companies like Exxon have made FID on projects, in part by building the whole value chain themselves or having one partner and a straightforward commercial agreement that works for both parties.

Having fewer players involved in projects can also help get projects moving faster, according to Stefan Ali, vice president of energy transition for Enerflex.

“You’re de-risking by taking multiple players away from the table.… When you bring in a whole bunch of parties that are trying to take one component of the value chain, you end up with risk in the system, and cost of capital that differ across the system, which makes it really challenging to put investment dollars to work,” Ali said.

Advancing technology also has a role to play in bringing down costs.

Enerflex is piloting some of these new technologies that are coming to market, examining what it would cost to use those technologies in the field and further optimization, he said.

“We’re seeing some improvements upward of 10%-15% of cost dropping out of the system just on the kit and process designs themselves,” he said.

Utilizing carbon

Utilizing carbon is another promising route to add value. EOR appears to be an obvious choice, given it’s already one of the top uses for CO2 in the U.S.

However, that can be an inconvenient and uncomfortable conversation when it can be seen today as perpetuating the fossil fuel industry, according to Chuck McConnell, executive director of the University of Houston’s Center for Carbon Management in Energy. That hasn’t deterred McConnell from backing CO2 for EOR, especially in “places like the Permian, where the opportunity for it is enormous beyond where it is today, limited by the amount of CO2 that can get to the Permian.”

Looking 20 years from now, the days of finding naturally-occurring CO2 underground will likely be gone, added Alex Shelby, director of investment banking for Barclays. “It’s more likely that we would see industrial sources of CO2 being earmarked and steered more towards EOR in the future,” he said.

Some companies are already advancing technologies that utilize CO2. These include combining CO2 with hydrogen to create e-fuels, a synthetic fuel that can be used in place of fossil fuels.

Chemically upgrading CO2 is difficult, according to Edward Stones, business vice president of energy and climate for Dow. In some cases, companies have been using process such as Fischer-Tropsch to convert CO2 into hydrocarbons.

However, “the economics get quite difficult. There’s some places you can develop methanol production, but the costs get pretty difficult to deal with in the industry that’s very focused on cost,” Stones said. “There’s a lot of saline aquifers that can be used properly for storage and for some people that’s more important for them.”

Recommended Reading

Not Sweating DeepSeek: Exxon, Chevron Plow Ahead on Data Center Power

2025-02-02 - The launch of the energy-efficient DeepSeek chatbot roiled tech and power markets in late January. But supermajors Exxon Mobil and Chevron continue to field intense demand for data-center power supply, driven by AI technology customers.

Phillips 66’s NGL Focus, Midstream Acquisitions Pay Off in 2024

2025-02-04 - Phillips 66 reported record volumes for 2024 as it advances a wellhead-to-market strategy within its midstream business.

Viper to Buy Diamondback Mineral, Royalty Interests in $4.45B Drop-Down

2025-01-30 - Working to reduce debt after a $26 billion acquisition of Endeavor Energy Resources, Diamondback will drop down $4.45 billion in mineral and royalty interests to its subsidiary Viper Energy.

Phillips 66’s Brouhaha with Activist Investor Elliott Gets Testy

2025-03-05 - Mark E. Lashier, Phillips 66 chairman and CEO, said Elliott Investment Management’s proposals have devolved into a “series of attacks” after the firm proposed seven candidates for the company’s board of directors.

EnLink Investors Vote in Favor of ONEOK Buyout

2025-01-30 - Holders of EnLink units voted in favor of ONEOK’s $4.3 billion acquisition of the stock, ONEOK announced Jan. 30.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.