Free cash flow is coursing through a sector that once exemplified value-destruction and some of the worst excesses in corporate America. (Source: Shutterstock.com; Hart Energy)

Living within their means has never been a strong point for U.S. shale producers.

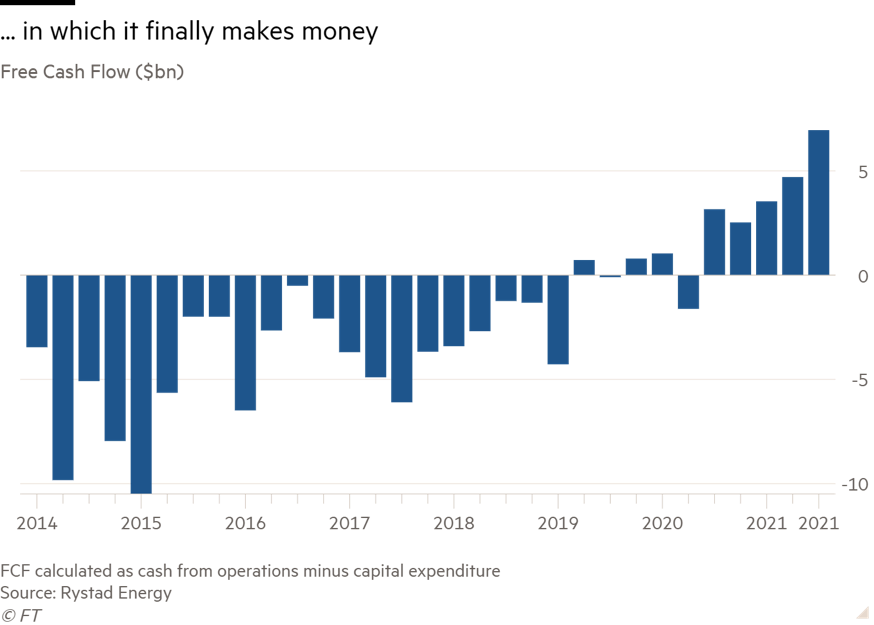

But last year’s crash, and colossal Wall Street pressure, have proven to be the nudge companies needed to get their houses in order. After years of burning through investor cash in pursuit of ever-greater growth, America’s shale patch is suddenly making money. Lots of money.

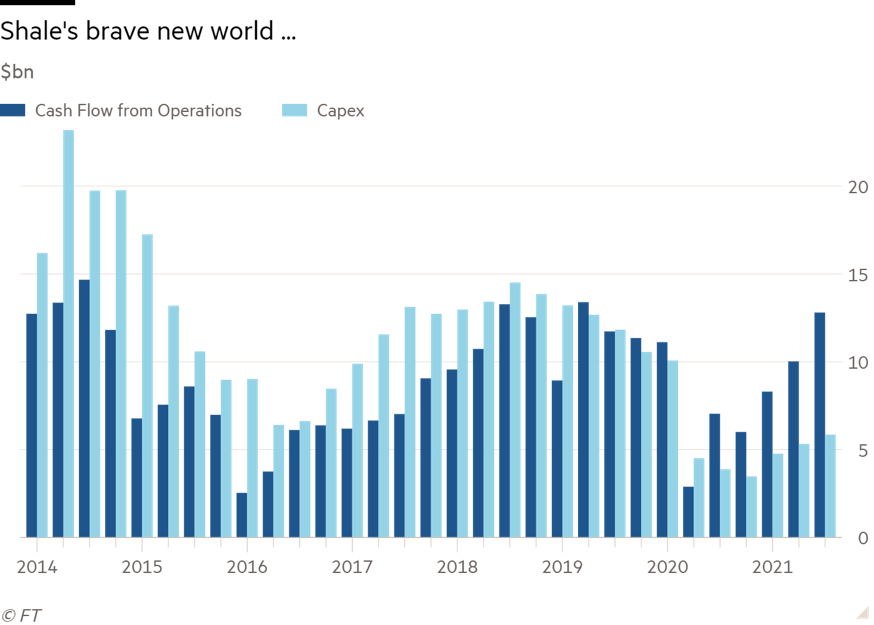

As 2021 rounds to a close, public shale companies shelled out a combined $6 billion in capex in the last quarter, according to consultancy Rystad Energy. That is less than a quarter of their levels at the height of the boom.

Cash from operations, meanwhile, sits at around $13 billion, approaching record levels.

All of which means that free cash flow, a key shale investor metric determined by the difference between cash from operations and capex, is coursing through a sector that once exemplified value-destruction and some of the worst excesses in corporate America.

The transformation—helped by a doubling in oil prices in the past 12 months—is stark, as the chart below shows.

It has been a long time coming. Investors have left oil and gas in droves in recent years, causing the sector to shrink from one of the biggest hitters on the S&P 500 to representing less than 3% of the index—half of Apple alone.

The old guard of growth investors have run for the hills, to be replaced with a new breed of value investors, keen on returns rather than untrammeled expansion of drilling.

“Our investors have evolved,” a senior shale executive told Financial Times during a recent visit to Midland, Texas. “They pushed for growth at all costs and now they get the new model and they like it . . . it’s important to them.”

That new model involves not injecting cash back into drilling new wells but rather funneling cash back to investors in the form of healthy dividends.

Scott Sheffield, CEO of Pioneer Natural Resources Co., the biggest shale player, described it in Houston last week as a new “contract” between the industry investors. In Pioneer’s case that means growing by no more than 5% annually and distributing a hefty chunk of free cash flow back to investors.

And this new model is here to stay, he told me: “There’s no way that the industry is going to change overnight and start growing again.”

Even as private operators put rigs back out in the field and look to ramp up drilling, public operators will be conspicuously cautious.

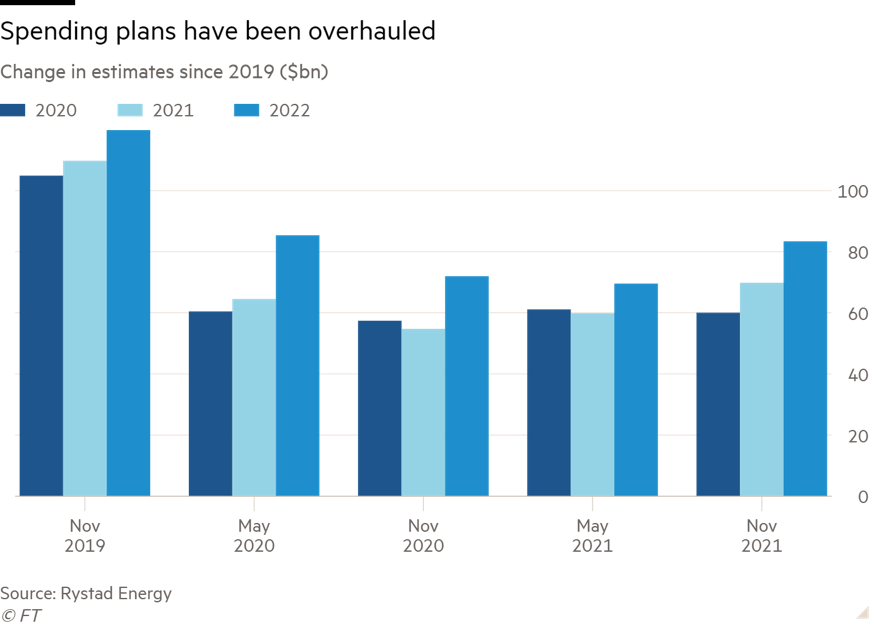

Before the pandemic, spending in 2022 was estimated to rise to $120 billion, according to Rystad. Now that figure looks closer to $80 billion.

It’s an easier approach, the Midland exec told Financial Times. It means companies don’t have to scramble to put out rigs, hire more workers and ramp up drilling every time the oil price picks up. Rather they can stick to a plan that stays constant whatever the price is doing.

“It’s a pretty volatile industry already,” he said. “So in the pyramid of craziness—oil price probably being the biggest—if we can control capital and control production, then investors can make a call on oil price, but we’re going to be OK in our plan.”

Will all this win back the old investors that fled the sector in recent years? The shale patch probably needs to get through another quarter or two of strong oil prices to prove its new fiscal discipline is here to stay. Judging from the XOP, an ETF often used as a proxy to judge market sentiment about the U.S. oil sector, which is up 63% this year, investors are warming to the new shale cash machines.

This article is an excerpt of Energy Source, a twice-weekly energy newsletter from the Financial Times.

Recommended Reading

New Jersey’s HYLAN Premiers Gas, Pipeline Division

2025-03-05 - HYLAN’s gas and pipeline division will offer services such as maintenance, construction, horizontal drilling and hydrostatic testing for operations across the Lower 48

McDermott Completes Project Offshore East Malaysia Ahead of Schedule

2025-02-05 - McDermott International replaced a gas lift riser and installed new equipment in water depth of 1,400 m for Thailand national oil company PTTEP.

Petrobras to Deploy Baker Hughes Completion Technology Offshore Brazil

2025-03-20 - Baker Hughes will be combining its completions technologies with conventional upper and lower completions solutions at Petrobras’ offshore developments.

PE Firm Voyager to Merge Haynesville OFS Firm with Permian’s Tejas

2025-03-17 - Private equity firm Voyager Interests’ Haynesville Shale portfolio company VooDoo Energy Services will merge with Tejas Completion Services as part of a transaction backing Tejas, Voyager said.

Equinor Begins Producing Gas at Development Offshore Norway

2025-03-17 - Equinor started production at its Halten East project, located in the Kristin-Åsgard area in the Norwegian Sea.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.