Exxon Mobil is getting serious about CCS. (Source: Shutterstock)

Developing carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) is no easy—or cheap—task. But Exxon Mobil is showing that its projects are not all talk, according to Carl Fortin, global business manager of carbon capture and storage for the supermajor.

That is the case on the U.S. Gulf Coast, where the energy giant and its partners are making moves in what Fortin said could be a $6 trillion global market by 2050. With its $4.9 billion acquisition of Denbury in 2023, Exxon Mobil now has the world’s largest CO2 pipeline. More than 900 miles of the company’s 1,700 miles of CO2 pipeline is on the U.S. Gulf Coast, where industrial emissions emitters make for a large customer base, plus storage.

In Baytown, Texas, Exxon is developing a low-carbon intensity hydrogen plant, using natural gas as feedstock and carbon capture. It plans to produce up to 1 Bcf/d of hydrogen while capturing more than 98% of the CO2 for storage underground. The CCS part of the project would be among the world’s largest, storing up to 10 million metric tons (mt) of CO2 per year—equal to the emissions from more than 2 million cars.

The CCS project is part of the Houston carbon capture hub that has brought together roughly a dozen companies to reduce industrial CO2 emissions. Exxon has lined up definitive agreements with customers from three industries: Linde, industrial gases; CF Industries, fertilizer manufacturing; and Nucor Corp., steel.

“These are actual projects in motion. The definitive agreements, the civil works, are either done or progressing well,” Fortin said on June 26 at the Hydrogen Technology Expo and CCUS North America conference in Houston. “The first one of these projects will roll out next year. So, CCS is alive and happening. … It’s not all just talk.”

Companies in the U.S. and abroad are turning to CCUS as a way to wrangle emissions amid global ambitions to cap global warming to about 1.5 C. Experts say CCS technologies are critical to hitting the target.

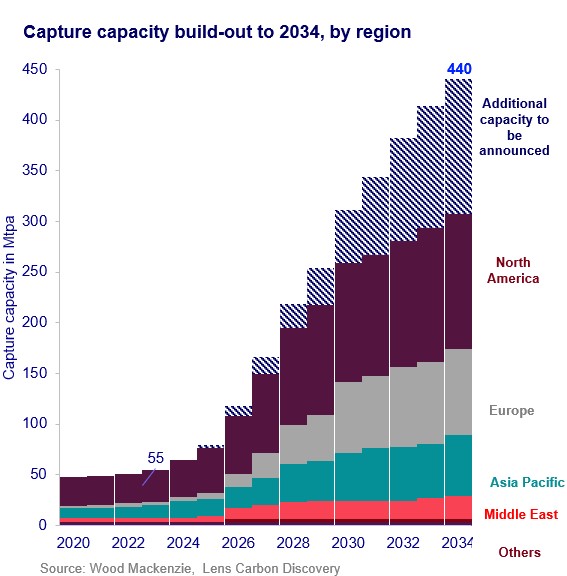

Soaring capacity

Global carbon capture capacity could reach 440 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) and storage capacity could rise to 664 mtpa by 2034. But the technology requires large investments: about $196 billion in total, according to a report released this week by energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie. About half of the investment needed is associated with carbon capture, with $53 billion for transport and $43 billion for storage. Most of the investment is expected to come from Europe and the U.S., where the 45Q tax credit is incentivizing CCS projects and bolstering the business case.

The U.S.’ 45Q tax credit offers $17/mt for sequestered, qualified CO2. However, the value jumps to $60 per ton for storage associated with enhanced oil recovery (EOR); $85 per ton for dedicated geologic storage; $130 per ton for direct air capture with carbon utilization; and up to $180 per ton for direct air capture with carbon storage.

“We see governments offering capex grants, opex subsidies, tax incentives and contracts for differences for CCUS,” Hetal Gandhi, APAC CCUS lead with Wood Mackenzie, said in a news release. “While no single mechanism has been used predominantly and each country devises novel methods to incentivize investments, nearly US$80 billion is directly committed to CCUS across five key countries.”

The U.S. accounts for half of the funding, according to Wood Mackenzie.

Getting more players

Many challenges remain to get some projects to final investment decision (FID). Expanding the opportunity for revenue for the captured carbon could encourage more investor buy-in.

“Policy is very important from an incentive standpoint to prime the pump. But also, we need to transition that to market-based valuation of the carbon,” Fortin said. “The more we can do that and bring more value and more certainty to it, you’re going to grow.”

Incentives are a big piece of a successful and investable CCS market, but “governments can’t afford to do it all forever,” he said, acknowledging the Inflation Reduction Act got the U.S. off to a start but only scratched the surface.

While more states granted primacy over CO2 injection wells will help, he added more sectors need to participate in unlocking the market.

CCS serves as the backbone for different decarbonization alternatives, he added.

CO2 is primarily used today in fertilizer production and for EOR, but it could also be used to produce e-fuels when combined with hydrogen.

Among the momentum builders for CCS, according to Fortin, is getting the cost of carbon reflected in low-carbon intensity products and having end consumers willing to pay to incentivize more decarbonization.

“It costs money to decarbonize to lower emissions. Somebody’s got to pay for it,” Fortin said. “We need to make sure we think of it from an investment standpoint so that those early projects are attractive. They’re robust. They serve as examples of the cash flows that can result, so that opportunities, in general, would be much more bankable.”

Lowering costs and improving the efficiency of networks with technology and partnerships such as those formed along the U.S. Gulf Coast can be replicated in other areas. “Those will go a long way to de-risk projects and get more to FID,” Fortin said.

Recommended Reading

Trump Says 25% Canada, Mexico Tariffs to Take Effect March 4

2025-03-03 - Financial markets fell on news that President Donald Trump would enact 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada and both countries promised to respond.

US Tariffs on Canada, Mexico Hit an Interconnected Crude System

2025-03-04 - Canadian producers and U.S. refiners are likely to continue at current business levels despite a brewing trade war, analysts say.

Oil Prices Fall into Negative Territory as Trump Announces New Tariffs

2025-04-02 - U.S. futures rose by a dollar and then turned negative over the course of Trump's press conference on April 2 in which he announced tariffs on trading partners including the European Union, China and South Korea.

Trump to Host Top US Oil Chief Executives as Trade Wars Loom

2025-03-19 - U.S. President Donald Trump will host top oil executives at the White House on March 19 as he charts plans to boost domestic energy production in the midst of falling crude prices and looming trade wars.

Trump Fires Off Energy Executive Orders on Alaska, LNG, EVs

2025-01-21 - President Donald Trump opened his term with a flurry of executive orders, many reversing the Biden administration’s policies on LNG permitting, the Paris Agreement and drilling in Alaska.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.