Michel Halbouty

Editor's note: This profile is part of Hart Energy's 50th anniversary Hall of Fame series honoring industry pioneers of the past 50 years and the Agents of Change (ACEs) who are leading the energy sector into the future.

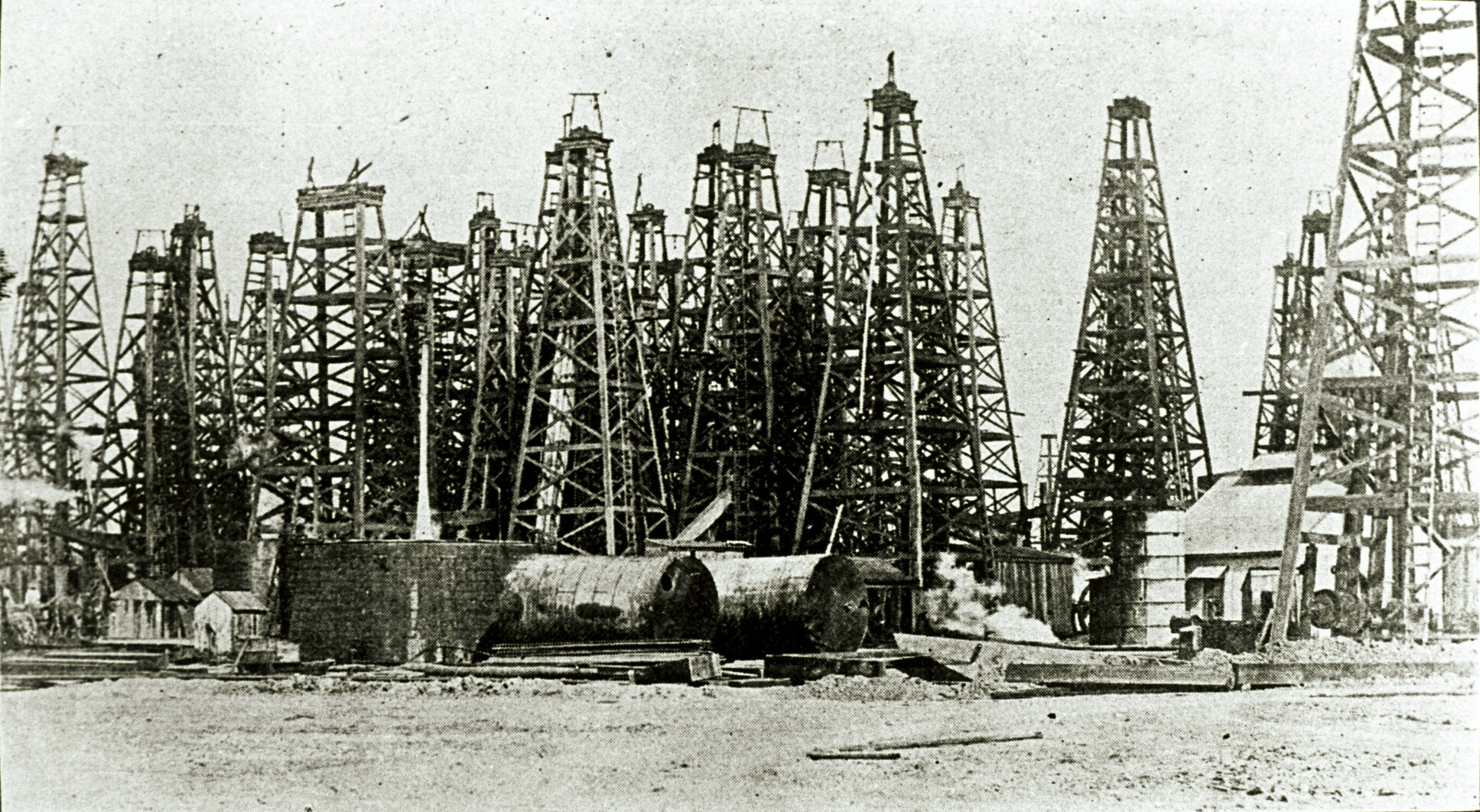

Michel Halbouty’s (1909-2004) entrance to the oil patch was as a boy lugging ice water to crews working the Spindletop field near his hometown of Beaumont, Texas. Throughout an illustrious career, he combined the resourcefulness and nerve of a wildcatter with the education and scientific discipline of an academic.

After graduation from Texas A&M University in 1931, he landed a job as a roughneck—one of the few in industry history with multiple degrees in geology and petroleum engineering. After Halbouty went out on his own and succeeded in bringing in well after well, he gained a platform to share his knowledge and concerns about threats to the industry and the country.

“I remember going to a speech that he gave one time, and I walked up to him and I said, ‘Daddy, how in the world could you talk like that for that length of time extemporaneously?’” his daughter Linda Fay Halbouty told Hart Energy. “He looked at me and he said, ‘When you know your subject, you can talk about anything.’”

In 1960, he spoke to the American Association of Petroleum Geologists in Los Angeles, decrying the country’s increased dependence on foreign oil imports and reduced investments in domestic exploration and production. It was a subject he knew well.

“History has demonstrated through such crises as World War II and Suez that foreign governments by deliberate action can deny the United States the use of foreign oil,” he said.

In a 1964 speech, he again implored his audience to take seriously the risk of a coming cutoff. “Probably before 1975 … the United States will have to start playing catch-up, the day someone, some group, some country, shuts down the valve on foreign oil.”

It was a prescient warning of the 1973 OPEC oil embargo, but received little notice outside the industry at the time, wrote Jack Donahue in his 1979 biography of Halbouty.

His first job after college was at a Yount-Lee Oil Co. field near Houston. The site, at High Island, was atop a salt dome, just as Spindletop was, but little oil had been found over the years and most drilling resulted in dry holes. Halbouty pored over drilling logs and maps in his off hours, trying to understand why this salt dome was not yielding hydrocarbons.

And then it came to him, Donahue wrote. The dome subsurface was shaped like a mushroom, not a barber’s pole like Spindletop. The oft-told story has Halbouty racing from the drilling site in his jalopy, slipping into Miles Frank Yount’s mansion during a formal party and convincing the furious oilman not to stop drilling Cade 21 because the most recent core sample showed that discovery was imminent.

Yount was convinced. Halbouty was right and the company was soon producing 75,000 bbl/d. A legend was born.

He would go on to drill in 26 states, including the first successful natural gas well in Alaska. He also wrote 370 articles and four books. He also received the Legendary Geoscientist Award from the American Geological Institute, as well as an honorary doctorate from the Soviet Union’s Academy of Sciences.

One of the greatest and most moving he received, said his daughter Linda Fay, was the Ellis Island Medal of Honor. It is “to those who have shown an outstanding commitment to serving our nation either professionally, culturally or civically,” the organization says on its website. Halbouty was among the 1994 class that included Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, Sen. Phil Gramm and magazine publisher Steven Florio.