President Biden’s LNG pause turned financially struggling Tellurian Inc.’s LNG export permit into a golden ticket—just as the company was facing a toll of debts, global events and a lack of board oversight that nearly bankrupted it. (Source: Shutterstock)

Tellurian Inc.’s eight-year journey from startup to exit is steeped in Netflix-worthy tales.

There is an eye-popping under-sight, global plague, epic run of canceled contracts, war, demand notices, political windfall and a foreclosure on the executive chairman’s ranch, yacht, home and his children’s homes too.

The executive chairman, Tellurian’s co-founder Charif Souki, was dismissed from the post on Dec. 8 after an investigation into undisclosed personal dealmaking with a Tellurian lender.

The CEO quit and the CFO resigned.

There was a surprise $250 million employee bonus package.

And the company was on the cusp of selling its land, while it had little cash on hand most days to fend off its creditors and pay its 168 employees.

Then suddenly, President Biden suspended issuing permits to new U.S. LNG projects.

In an instant, the Jan. 26 announcement made Tellurian’s fledgling plans for an LNG export plant more valuable: It had an existing, active permit.

Putting its Haynesville shale E&P portfolio on the market would buy it time to summer while it was going broke. But it would net little cash: The proceeds were obligated already to pay off a debt that was secured by the E&P property.

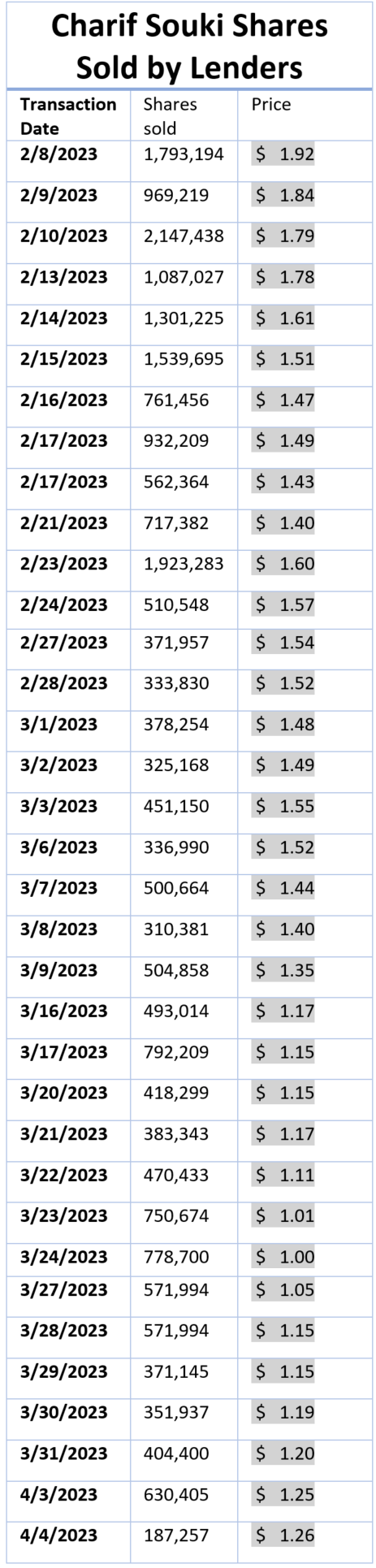

Its stock price tumbled as Souki lost 25 million Tellurian shares in a foreclosure on a personal loan and the lender dumped the stock into the market.

After a lender seized 25 million shares Tellurian shares from the company’s founder, Charif Souki, it began selling them off even as the weighted price began to drop. (Source: Securities & Exchange Commission filings, Hart Energy)

The company was running out of time to pursue solvency options other than to sell the rest of its property: an LNG export permit and the plant property.

In July, it had one firm bid: $1 a share.

Sold.

Souki told Hart Energy on Sept. 4 that he is now building a position in Woodside Energy stock, totaling at least six figures to date and on a path to seven figures.

He said he couldn’t comment on his dismissal and the Tellurian board’s decision to sell—due to a non-compete in effect through year-end.

But “I did read the proxy statement, so I know what they say,” he added.

“I don't agree with them, but I can understand how people can disagree in good faith.”

The review

Tellurian unpacked it for shareholders in its Aug. 27 proxy statement, explaining the background on the plan to exit to Australia’s Woodside Energy, a 35-year LNG exporter, in a deal for $900 million in cash for the stock.

With assumption of debt and other liabilities, the total deal value is $1.2 billion, according to Woodside.

Hart Energy reviewed more than 150 documents, including prior Tellurian filings with the Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC), filings involved in Souki's federal civil court and bankruptcy cases, and other public records.

Jacob Frenkel, a former senior counsel in the SEC’s Division of Enforcement and a former federal criminal prosecutor of securities violations, reviewed a Hart Energy summary of the details.

“SEC statutes and regulations are a robust disclosure regime that requires, among many things, reporting—accurately—related-party transactions and prohibiting providing material non-public information on which individuals may decide to trade,” he replied.

Frenkel is currently chair of law firm Dickinson Wright’s government investigations and securities-enforcement practice.

“Well-advised companies require their officers and directors, in connection with proxy disclosures and annual reporting, to report conflicts and potential conflicts of interest,” he added.

“In scenarios, as here, where there is an appearance both of non-disclosure of potential related-party transactions or conflicts of interest and possible trading while in possession of material non-public information, the SEC’s Division of Enforcement takes interest and investigates.”

The three contracts

To remain afloat the past four years, the aspiring LNG exporter had issued $825 million worth of shares; sold $50 million of preferred shares in 2018 to plant contractor Bechtel Corp.’s BDC Oil & Gas Holdings unit; sold notes; and took loans from various other parties.

Meanwhile, building all phases of its Driftwood LNG project south of Lake Charles, Louisiana, was estimated to cost $25 billion, according to the Aug. 27 proxy.

The first phase will include capacity of up to 11 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) or 1.5 Bcf/d. All phases would total 27.6 mtpa (3.7 Bcf/d) of liquefaction capacity on its 1,200 acres—mostly owned; some leased—on the Calcasieu River’s west bank near Sempra Infrastructure’s Cameron LNG plant.

It had a deal in 2019 with TotalEnergies, which at one time held a 19% position in outstanding Tellurian shares. But the international energy company withdrew in 2021 as Tellurian had not yet reached a final investment decision (FID) on plant construction.

As global LNG prices spiked in the first half of 2022 upon Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Souki ordered construction on Driftwood’s Phase 1 to begin, although Tellurian didn’t yet have enough financing to make a full FID on the project.

An FID is needed to keep a permit under Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) rules. Currently, FERC is requiring Driftwood’s completion by 2029.

In other deals, Tellurian had 10-year sales contracts with Gunvor Group, Vitol and Shell for a combined 9 mtpa by early 2022, which a J.P. Morgan Securities analyst said at the time would “more than cover the [11 mtpa] first phase of the Driftwood project.”

That summer, the company was able to raise $500 million by selling 6% convertible notes secured by its Haynesville E&P property in northwestern Louisiana.

Now, no contracts

Then the tide turned. Later in 2022 and into 2023, all of the buyers canceled.

Global LNG prices had retreated from an early 2022 price spike to more than $80/MMBtu as European countries secured non-Russian supplies.

And the owner of the 6% debt secured by the E&P property called in $166 million of the notes for cash.

While world LNG prices had returned to roughly $10/MMBtu, U.S. natural gas prices had free-fallen from about $9 to $2.

The Haynesville property’s value had declined in step.

Then, Tellurian discovered that Souki had loans from banker UBS O’Connor and three others that were secured by personal property, including Tellurian shares, while UBS O’Connor had also banked Tellurian.

The news broke when Souki sued UBS O’Connor, which describes itself on its website as a provider of “bespoke lending solutions,” and three others: its hedge fund Nineteen77 Capital Solutions, Cayman-based Bermudez Mutuari and a bank, Wilmington Trust.

UBS O’Connor had sold 25 million of Souki’s shares in February and March of 2023, “putting significant downward pressure on the trading price of the company’s stock,” Tellurian reported Aug. 27.

The stock’s price fell from about $2 at the beginning of February to $1 by the end of March.

Separately, two Souki-owned companies filed for bankruptcy—Ajax Holdings, which was the family’s Aspen, Colorado, real estate developer, and Ajax Cayman, which owned Souki’s 100-foot sailing yacht.

“The board formed a special committee to investigate these matters,” Tellurian stated Aug. 27.

Eye-popping under-sight

The filing did not state, though, whether the Tellurian board or shareholders had ever asked Souki about the loan counterparties’ identities, although Tellurian had reported annually that shares Souki controlled were collateral in a loan.

Tellurian did not reply to a Hart Energy request for comment by press time.

The company’s first disclosure of the discovery was in its May 2023 annual report.

“Our executive chairman, Charif Souki, has personal investments and interests that have at times become interrelated with the interests of the company. These investments and interests may result in conflicts of interest or other impacts on the company,” it wrote in the SEC filing.

In particular, Tellurian reported it discovered in Souki’s suit that he and UBS O’Connor “agreed in 2020 to approach the renegotiation of the terms of the Souki loans and the [2019] Tellurian loan ‘holistically,’ an agreement that was not disclosed to the company.”

It added, “Policies and procedures designed to mitigate potential conflicts of interest are subject to inherent limitations and may not result in all such conflicts being identified and addressed in a timely manner.”

Well known

Souki’s debt involving his Tellurian shares was well known by the company, according to its previous SEC filings, which do not also disclose whether Tellurian was aware of the identities of Souki’s lenders.

His first loan led by UBS O’Connor was made in 2017, according to his lawsuit.

An August 2017 Tellurian proxy statement disclosed that Souki pledged 2 million of his shares in June of 2017 to secure a $5 million bank line of credit.

In April 2018, Tellurian’s proxy statement reported that Souki pledged 1 million shares in a margin loan from a bank in October 2017 and that the 2 million shares pledged in a line of credit in June 2017 were moved to the margin account that held the 1 million shares.

In addition, Souki pledged 20 million shares in January 2018 in a “loan facility extended by another bank,” Tellurian added in the 2018 proxy statement.

At that time, UBS O’Connor did not have any deals with Tellurian itself, according to various documents.

In the spring of 2019, Tellurian’s proxy statement reported Souki had 25 million shares pledged in “a collateral package to secure a loan for certain real estate investments.”

Also, it reported, the Souki family trust had 23 million of its 26 million shares pledged “as part of a collateral package to secure financing for various investments.”

By then, Souki’s direct and indirect shares had grown to a meaningful amount of public float: 54.6 million (22.6% of outstanding).

Within a year, that fell to 28.5 million (10.7% of outstanding), according to the 2020 proxy statement. The family trust no longer held shares, which totaled 26 million a year earlier.

Meanwhile, of Souki’s remaining 28.5 million shares, Tellurian reported 25 million were “part of a collateral package to secure a loan for certain real estate investments.”

The SEC filings don’t indicate whether Tellurian’s board asked Souki what happened to the family trust’s shares.

Tellurian, UBS O’Connor

In May of 2019, Tellurian made deals with Souki’s lenders. It issued 1.5 million warrants to UBS O’Connor’s Nineteen77 Capital Solutions. Separately, it borrowed $60 million in a senior secured term loan from Wilmington Trust.

At least one of Souki’s fellow board members was aware of the Souki family trust’s loans. Brooke Peterson, who is also an Aspen municipal court judge, had held an irrevocable power of attorney through year-end 2020 to vote the family trust’s shares, according to the 2019 proxy statement.

Souki was the trustee and decisions were made by majority vote of his children, including Tarek Souki, who is Tellurian’s executive vice president, commercial.

At the time, Peterson was also manager of the Souki family’s Ajax Holdings since December 2012 as well as CEO since January 2013 of Aspen-based Coldwell Banker Mason Morse, the family’s real estate firm.

He left these posts in May 2022, according to a 2023 proxy statement.

Lost almost all of them

As Tellurian issued more stock to remain afloat, Souki’s holdings diminished to 7% of outstanding in 2021.

A footnote in that year’s proxy said simply again that 25 million of Souki’s shares were “part of a collateral package to secure a loan for certain real estate investments.”

With stock awards as part of compensation, his holding grew in 2022 to 30 million shares. But Tellurian’s continued equity sales diminished his position to 5.2% of outstanding.

Then suddenly, he lost almost all of them.

The April 27, 2023, proxy statement reported his holding as 8.3 million shares (1.5% of outstanding), including 6.7 million subject to options exercisable by June 20.

By this past spring, Souki owned just 1.7 million shares.

Boom, bust, bust

In late 2022 and early 2023, the lender group had foreclosed on the shares as well as the family’s homes, its other Aspen real estate held by Ajax Holdings and Souki’s yacht held by Ajax Cayman.

Born in Egypt and spending his youth in Lebanon, Souki, the son of a foreign news correspondent, had settled in Aspen after retiring in the early 1980s while in his early 30s from the international investment banking lifestyle of home- and hotel-hopping in New York, Paris and the Middle East.

In Aspen, he opened a successful restaurant, Mezzaluna, which he sold in 1993 and remains in operation today.

From that venture, he set off for the oil and gas business in Houston, founding an E&P, Cheniere Energy Inc., in 1996 that became an LNG importer in 2008 and was virtually mothballed on opening day when colliding with a newly flush supply of U.S. shale gas.

Undeterred, he built an adjacent plant to export LNG from the southwestern Louisiana property that has since grown to 4.6 Bcf/d of capacity with three berths.

But activist investor Carl Icahn pushed Souki out in 2015 over Souki’s compensation package—estimated at $142 million a year—that made him what was considered to be the highest paid executive in the U.S. at the time.

He swiftly founded Tellurian with friend Martin Houston, a former BG Group executive, in 2016 and took it public via a reverse merger in 2017 with penny stock Magellan Petroleum Corp.

‘Begged’ him

In his lawsuit filed against UBS O’Connor and the three other lenders in March of 2023 over their foreclosure, Souki called their actions “unconscionable.”

They loaned him $90 million in 2017 and 2018 against collateral of 25 million Tellurian shares, the 800-acre Aspen ranch that included his and his children’s homes, “and his prized sailboat,” he told the New York Southern District federal court.

He added that, “in 2019, defendants loaned $60 million to Tellurian without disclosing the Souki loans to Tellurian” and “in 2020, when Tellurian was near bankruptcy,” they “begged” him to ensure Tellurian would repay its debt.

“In exchange, [the lenders] promised Souki they would be flexible in their approach to repayment of his loans and would not act in ways that materially disrupt Tellurian’s stock price,” he told the court.

But “these were empty promises” that the lenders “had no intention of honoring,” he added.

Tellurian paid off the lenders in March of 2021, a year before maturity.

“Almost immediately” they demanded $5 million from Souki and full repayment, which had grown to $103 million with interest, by Oct. 30, 2021, Souki told the court.

They also “threatened to foreclose on his ranch and pressured him to sell his Tellurian stock in ways that would likely violate securities laws,” his suit reported.

He refused their demands and they increased the interest rate, he added.

The lenders were now “selling his sailboat at a bargain basement price and are now selling Souki’s Tellurian stock so recklessly that it has driven the stock price down nearly 25%,” he said in the March 2023 suit.

Souki had paid a $50 million loan taken in 2017 down to $30 million in early 2018, he wrote. He borrowed another $70 million and brought the balance down to $90 million, secured by the Tellurian shares, the family’s Aspen Valley Ranch and his equity interest in Ajax Holdings and Ajax Cayman.

Maturity was initially January of 2019.

They didn’t say; he didn’t say

In May of 2019, he told the court, he introduced the Tellurian board to UBS O’Connor and the lending group but didn’t get involved in negotiations.

The group didn’t disclose to the board its relationship with him, he added, when UBS O’Connor’s Nineteen77 Capital Solutions bought stock warrants and Wilmington Trust loaned Tellurian $60 million.

Souki did not mention to the court if he disclosed the relationship to the board.

But, he told the court, “this created an inherent conflict of interest for [the lenders].”

The lenders could have affected Tellurian’s stock price if foreclosing on and dumping Souki’s stock and “this is something Tellurian would have wanted to know and protect against before entering into the loan,” he told the court.

Throughout this time, Tellurian shares were averaging about $8 on the market.

But they tanked to less than $1 in early 2020 as global gas demand slumped in the midst of COVID lockdowns.

The 25 million shares were worth about $24 million then.

He got the lenders to agree to not foreclose on him “while he focused on repayment of the Tellurian loan,” he wrote in the lawsuit.

Souki, who had been Tellurian’s chairman, took the executive chairman position in June of 2020 to work on “righting its financial ship and in repaying expensive debt, including the Tellurian loan [that involved his own lenders],” he told the court.

Moving out

With the UBS O’Connor group at the ranch’s gate, Souki asked family members who lived in some of the homes on the property, “most of which had been built by my family,” to move out and listed the homes for rent and for sale, he told the court.

Buyers offered a combined $46.5 million for three of them. He expected the net proceeds would allow him to pay $30 million to Alpine Bank, which had a lien on the homes and lots, leaving $12.6 million to send to the UBS O’Connor group.

In April of 2022, the lenders increased the interest on his loans to the 15% default rate.

A few days before Christmas, they seized Souki’s sailboat, Tango, which was undergoing regular maintenance and repairs, listing it for sale “as is, where is,” he wrote.

On Feb. 8, 2023, they followed with seizing the 25 million Tellurian shares, dumping them into the market during the next 57 days, initially for nearly $2 and down to as low as $1.

Souki concluded in his lawsuit that, if the lenders had sold the shares in April of 2022 while they were $6, his debt would have been paid, he would have shares left over “and the rest of his collateral would not be subject to foreclosure.”

Ultimately, the 25 million shares went for $37 million.

He told the court that the lenders violated securities law for trading stock while having Tellurian insider information, which he had been provided to them when he argued for giving him more time to improve Tellurian’s stock price.

The yacht, the house

Built in 2017, the Cayman-flagged sailing yacht, Tango, was sold in the spring of 2023. Now known as V, the boat is a 100-foot Wally-built monohull designed by naval architect Mark Mills and accommodating four crew and six guests, according to SuperYacht Times.

Souki told the court that it took him three years to design and build the boat “and I was intimately involved in that process. It is very much a unique asset that I treasure.”

As for his and his wife’s home on the ranch, he wrote in the lawsuit that “the ranch is still my primary residence and it is an extraordinarily unique property that has taken nearly two decades to put together and cannot be replicated.”

In addition, “the sentimental and familial value … could never be replaced.”

To lose his own home “would render me homeless [in the U.S.],” he added. (He has two homes in France, he told Hart Energy earlier this month.)

He no longer had the ranch for sale, he added in a supplemental court filing. “We plan to keep the ranch in the family.”

His separate bankruptcy case, filed in Houston, was dismissed Aug. 16 after mediation.

What was left of the collateral—the downtown Aspen commercial real estate—was sold to a Chicago-based developer for $62 million in early August, according to Aspen Daily News.

Peterson, the Aspen city judge, remained on the board until this past March when he resigned, citing health.

Tellurian’s ‘going concern’

In the midst of the 2023 fallout from the Souki loans discovery, Tellurian launched a new round of looking for takers for its LNG—contracts it needed to finance continued construction of Driftwood to meet the FERC-issued 2029 deadline for completion.

The targets were “large investment-grade energy companies with LNG trading expertise,” it reported in the Aug. 27 proxy statement.

Among them, it met with Woodside CEO Meg O’Neill at an LNG conference in Vancouver that July.

In September, it met with a company it identified in the proxy statement as “a global investment fund focusing on energy infrastructure.”

Tellurian had refinanced its remaining convertible notes by issuing $83 million of new notes as well as $250 million in non-convertible.

That plugged one hole, but continued Driftwood construction costs as well as a sub-$3 price for its Haynesville gas resulted in less cash on hand.

By early October, it reported to shareholders “there was substantial doubt regarding its ability to continue as a going concern for the next 12 months.”

Signing up long-term LNG offtakers was essential to refinance its debt, sell equity at a decent price or have any cash on hand, it reported in the Aug. 27 proxy statement.

Another unidentified entity described as “an energy-focused investment fund that held an interest in another LNG liquefaction project” got in touch in September 2023 and received a briefing on progress to date on Driftwood.

At an industry conference in London, Tellurian co-founder Houston, who was vice chairman at the time, let O’Neill know that the board “would consider any transaction proposed by Woodside, including a sale of the company,” the proxy statement reported.

A couple of months later, the board learned that the investment fund was interested but that it intended to partner with Woodside in any proposal.

O’Neill added that any proposal to Tellurian depended on winning a reduced contract cost from Bechtel for building the Driftwood plant. (Bechtel was already Woodside’s contractor in its Australian LNG export operations.)

Souki out

Souki’s lawsuit against UBS O’Connor and the other lenders was set for trial on Dec. 11.

The board fired him on Dec. 8 after discussing the “impact of the trial on the trading price of the company’s stock, potential financing transactions and its ongoing commercial discussions,” Tellurian reported.

In-house attorney Daniel Belhumeur became president. Octavio Simoes remained CEO but resigned this past March after his contract was not renewed. He remained a special advisor as of last month.

Kian Granmayeh had departed as CFO in March of 2023 for another job. Simon Oxley, an investment banker for Barclays, was hired for the post the following May.

Houston assumed the chairman post and, in February, the executive chairman position Souki had been dismissed from in December.

While Souki was going to bankruptcy court in Houston on Dec. 11, Tellurian met in Washington, D.C., with Reston, Virginia-based Bechtel along with Woodside’s O’Neill.

Separately, while Woodside and its investor partner continued discussions with Bechtel, Tellurian board members received an update just before Christmas on the company’s solvency.

Meanwhile, an unidentified, publicly traded, pipeline company initiated a conversation with Tellurian about signing an LNG offtake contract.

Separately, Tellurian hired investment banker Lazard Inc. to look into how it could raise some money.

The pause

A sale of the company was not yet being discussed, although Houston had told Woodside in London that Tellurian would consider a sale of the company, according to the Aug. 27 proxy.

Then, Biden issued a pause on issuing permits to new LNG projects on Jan. 26.

Suddenly, the Driftwood permit was of limited edition.

The Tellurian board’s meeting a few days later included discussion of progress in raising capital “and recent market and regulatory developments,” it reported in the proxy.

The investment fund that held a permit for another LNG project met with Tellurian on Feb. 1 about combining the projects. A week later, the two discussed the fund taking an offtake contract with Driftwood, buying some of Tellurian’s debt and/or other financing.

Tellurian press-released that its Haynesville E&P property was for sale. By late May, 28 potential buyers had signed confidentiality agreements and five bid.

As for the balance of Tellurian’s property—the land and the LNG permit—Woodside informally said in a videoconference that its offer would be $700 million.

To check other options, Lazard was hired to reach out to more than 40 parties, in addition to leading the E&P divestment assignment.

Among them, 10 signed non-disclosure agreements and, in the next 60 days, eight listened to Tellurian management presentations.

The pipeline company that had earlier indicated interest in a deal with Tellurian joined with two E&P companies and proposed they become a co-owner with Tellurian in Driftwood.

But the trio later said the structure was no longer viable.

The bonuses

In March, Woodside and its investor partner offered $1.15 worth of Woodside stock per Tellurian share.

But the offer was only if it could win a cost cut from Bechtel, get financing, Tellurian continued to retain its permit and there would be no surprises in change-of-control payments due employees post-closing.

Soon, it learned it would have to pay current and former Tellurian employees $250 million in bonuses in a “construction incentive program” (CIP) if the company is sold.

At year-end 2023, Tellurian had 168 full-time employees. Woodside learned that 80% of the $250 million would go to 20 current and former employees.

It replied that the sum would have to be reduced or the difference in what Woodside had estimated bonuses would total versus the real sum would be trimmed from the purchase price.

And it twisted Tellurian’s arm one more turn: It added that it wouldn’t pay Tellurian’s bills prior to signing a definitive purchase agreement.

Souki with a term sheet

Tellurian had options but it was running out of money, which “could affect its ability to pursue those options,” it reported in the Aug. 27 proxy statement.

Among them by late April, it had a buyout offer from Woodside, bids in on its E&P assets, an investor’s offer of a direct investment if Tellurian would combine its Driftwood project with its own, two other offers of direct investment and several potential offtakers with interest.

Although having an active bankruptcy filing, Souki showed up with an offer to buy between $100 million and $200 million of newly issued Tellurian shares, which were trading at about $0.40 at the time.

The board was doubtful about the option “due to concerns about the likelihood a transaction would be completed and potential regulatory issues,” Tellurian reported.

Souki got a meeting, reiterating that he would raise $100 million to invest in Tellurian and followed it up with a term sheet 10 days later.

The board declined, deeming Souki’s offer “to be, among other things, highly speculative,” it reported Aug. 27.

Aethon shows up with cash

In early May, Tellurian and Woodside commenced pencil-fencing on merger terms and Woodside’s investor partner bowed out, saying one of its principals couldn’t approve a deal for at least the following two months.

On May 28, privately held Haynesville-focused operator Aethon Energy placed a winning $260 million bid on Tellurian’s E&P property, consisting of 31,000 net acres and up to 100 MMcf/d of treating and gathering capacity.

It also signed a heads of agreement (HOA) to discuss a 20-year deal to buy 2 mtpa (267 MMcf/d) of LNG from Driftwood.

Aethon and Tellurian issued the press release on May 29.

The stock price improved from about $0.50 to $0.88.

With the E&P property jettisoned, its negotiations were now for a pureplay LNG company—and one with at least one HOA in hand.

Tellurian by the tail

While the company was to receive $260 million from Aethon at closing June 28, most of the proceeds went to the 6% lender, since the property was collateral in the note.

Fund-raising options were now to sell the rest of Tellurian’s real property, sell shares and win financing from the investment fund that was developing another LNG project.

It had received a bid from another potential offtaker but the offer was too low, Tellurian reported, and “could establish a precedent for discussions with other potential purchasers.”

The offer was declined.

While the HOA with Aethon increased interest from other potential offtakers, “new agreements were unlikely to be entered … in the near term,” the board concluded.

Woodside arrived with a revised bid: $0.94 in cash per Tellurian share.

In addition to being less than the $1.15 worth of Woodside stock per Tellurian share that was initially offered, a cash buyout would be a taxable event for Tellurian shareholders.

Woodside explained that the reduced bid was the result of its due diligence and because Tellurian had more shares outstanding than when it made the $1.15 offer, according to the Aug. 27 proxy.

But it threw in a bridge loan—sweetening the pot with something that could keep Tellurian afloat, which Woodside would need if wanting to buy a solvent company with an active LNG export permit.

Houston told O’Neill that the board would likely find the offer “inadequate.”

Woodside returned in late June with $1 per share and said that was “the maximum amount it was willing to pay.”

Meanwhile, Tellurian said some of its senior officers would agree to 40% less CIP bonus. Woodside replied that they would have to agree to a 70% reduction.

As for the investment fund that was interested in combining its LNG project with Driftwood, odds of a potential deal getting done quickly “were insufficient to justify continued negotiations,” the board determined.

The end

On July 8, Tellurian pushed back on Woodside’s offer, but O’Neill didn’t budge and instead submitted “a draft of the merger agreement which largely reverted back to Woodside’s initial positions,” the proxy statement reported.

Tellurian convinced nearly all of the officers involved in the CIP bonus to take a 70% cut.

No one but Woodside had made a firm offer to buy Tellurian, the board noted in a July 21 meeting.

It voted to do the deal for $1 share that came with a bridge loan of up to $230 million, representing “the best combination of value and certainty for the company’s stockholders,” Tellurian reported in the recent proxy statement.

The company borrowed $75.2 million from the line of credit the next day.

Cash on hand had been $19 million. Debt totaled $134 million due 2025 and 2028.

Shareholders are to vote on the deal Oct. 3.

Next for Souki

Souki spoke to Hart Energy on Sept. 4 from his home in Paris—he also has one on the coast of France—and planned to return this fall to his Aspen home, which he kept.

He has moved on from the yacht. “I wish the person who owns her now enjoys her as much as I did,” he said.

He is in a non-compete with Tellurian through year-end.

“So at the moment, I'm going to stay on the sidelines. But as you can imagine, I have some ideas.”

(Editor’s note: A Q&A with Charif Souki will be published separately.)

Recommended Reading

Congress Kills Biden Era Methane Fee on Oil, Gas Producers

2025-02-28 - The methane fee was mandated by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, which directed the EPA to set a charge on methane emissions for facilities that emit more than 25,000 tons per year of CO2e.

Belcher: Texas Considers Funding for Abandoned Wells, Emissions Reduction

2025-03-20 - With uncertainly surrounding federal aid as the Trump administration attempts cost cutting measures, the state is exploring its own incentive system to plug wells and reduce emissions.

Report: Trump to Declare 'National Energy Emergency'

2025-01-20 - President-elect Donald Trump will also sign an executive order focused on Alaska, an incoming White House official said.

Industry Players Get Laser Focused on Emissions Reduction

2025-01-16 - Faced with progressively stringent requirements, companies are seeking methane monitoring technologies that make compliance easier.

Pickering Prognosticates 2025 Political Winds and Shale M&A

2025-01-14 - For oil and gas, big M&A deals will probably encounter less resistance, tariffs could be a threat and the industry will likely shrug off “drill, baby, drill” entreaties.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.