As decarbonization policy continues to evolve on a global scale, carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) adoption is gaining momentum. Endorsed by many prominent trade bodies as a necessary catalyst for unlocking decarbonization at scale, CCUS offers a pathway for industries that previously would have found it hard to decarbonize, such as cement, glass and pulp and paper.

With the increase of the 45Q tax credit for carbon capture projects through the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022, coupled with the funding in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Legislation (BIL), the U.S. government is signaling a shift in focus from research and development to scale and commercialization of carbon capture technologies. Companies in the U.S. can potentially access government grants to build carbon capture projects, as well as incentives to operate them.

To successfully deploy carbon capture at scale, projects must consider the carbon capture itself, in addition to the transport and final destination of the CO2. Installing a new CO2 pipeline and planning for sequestration and/or end-use is an expensive effort for just one company to undertake.

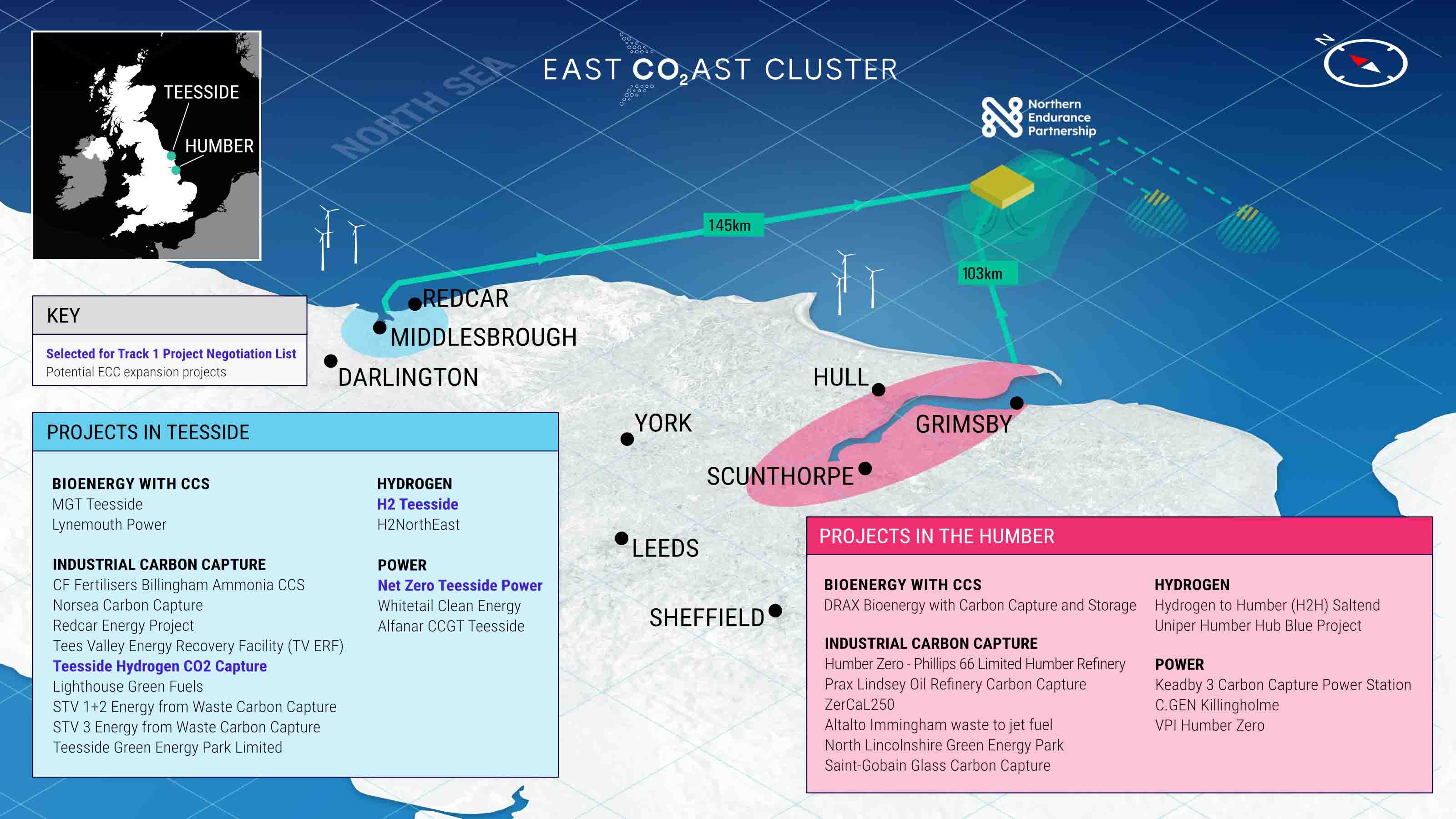

A more cost-effective approach is for groups of emitters to partner on transportation and storage projects for mutual benefit, a practice now commonly referred to as a “hub” or “cluster.” Hubs are increasing in popularity in the U.S. and beyond and are recognized as a viable model for advancing industrial decarbonization projects. Well-known examples include the U.K.’s East Coast Cluster, Canada’s Pathways Alliance and Houston’s HyVelocity hydrogen hub, which includes a significant carbon capture component; however, these projects are still being developed and have not yet delivered emissions reductions.

RELATED

Hydrogen Hubs Across US Submit Plans for $7 Billion in DOE Funding

With most carbon capture projects still in the FEED and pre-FEED phases, early engagement with experts is essential. Without a clear understanding of which carbon capture technology will work best or a clear plan to transport, store or use the CO2, CCUS will not reach the commercial status it needs to maintain momentum.

CCUS in action

Providing the world with clean, affordable, secure energy and materials will require us to balance the investment of capital and technology between existing facilities and greenfield developments. The reality is, we do not yet have commercially viable routes to produce all the commodities we rely on today without the use of fossil fuels as a key feedstock. But CCUS could offer us a practical way to address this issue.

With billions of dollars in grants from the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) and increased tax incentives from 45Q, Wood is moving forward with projects focused on accelerating the commercial deployment of CCUS technologies at scale. Solutions such as direct air capture (DAC) hubs, carbon capture for industrial decarbonization and hard-to-abate sectors, and CO2 pipelines are advancing at an accelerating pace, indicating carbon capture’s growing appeal.

Despite the increased interest in CCUS, as of 2023, only 40 commercial facilities were operational in industrial processes, fuel transformation and power generation; that’s a small share of the 500 projects in the pipeline. The Energy Transitions Commission (ETC) has estimated that by 2050, the world will need to capture and either use or store 7 gigatons to 10 gigatons per year of CO2, a huge jump from today’s 46 million tonnes per annum. The current pace of deployment for carbon capture technology falls short of allowing us to meet this goal, meaning serious action must be taken to ramp up CCUS if we are to reach sufficient capacity in the coming decades.

Barriers to scaling up

The scale and deployment of CCUS poses technical, commercial and policy challenges. Understanding the basics of carbon capture technology is fundamental. Typically, when companies decide to decarbonize, they must select a licensor’s technology from a pool of many options. Not all emissions are the same. The range of concentrations and contaminants can vary widely in industry. It is critical that stakeholders understand the carbon capture technology’s capabilities and operating parameters to ensure it will meet their decarbonization needs.

For some of these industries, the most well-proven technology for post-combustion CO2 capture, an amine system, is a significantly different type of unit to the existing processes on the site. Similarly, the project development process may also be unfamiliar. Many producers in the commodities industries are accustomed to an off-the-shelf approach to buying units or system components. However, carbon capture units, especially amine-based ones, are typically bespoke designs that need to go through the pre-FEED and FEED development steps. This enables operators to optimize the system while minimizing investment and operating costs. It also stops existing operations and the surrounding environment from being seriously impacted during the carbon capture system’s implementation.

Historically, project economics have been a “make or break” factor for carbon capture projects as well. For example, in 2017, Petra Nova began capturing CO2 at a Texas power plant and transported the CO2 by pipeline for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) in a nearby oil field. The project originally cost around $1 billion to build. When the price of oil plummeted in 2020, the carbon capture unit was turned off because the increased oil production no longer produced enough profit to justify running the CO2 capture operation. The carbon capture unit restarted in 2023, but the lesson on the importance of CCUS project economics remains.

Ensuring projects are technically and economically sound is imperative if carbon capture technology is to achieve its full potential. This is why operators and manufacturers are encouraged to engage specialist decarbonization and technical advisers from the onset.

Beyond this, policy momentum must continue to accelerate to fully unlock the potential of CCUS to advance the energy transition. We have already made exceptional policy progress in the U.S., but replicating this on a global scale is far more difficult. Creating standard forms of carbon accounting for the global supply chain will be key for driving further engagement with CCUS solutions. A clearer understanding of the emissions associated with the production of a particular product can enable countries to implement policy to further their own objectives.

The EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is a brilliant example of bringing this into practice. By putting a price on the carbon emitted during the production of goods entering the EU, it encourages cleaner industrial production in non-EU countries. Policies such as CBAM help move the needle on decarbonization projects worldwide. We have seen projects in the U.S. pivot their strategies to optimize U.S. tax incentives as well as CBAM.

Pulling this type of targeted carbon policy to the global market will be no easy feat, but the benefits associated with doing so will be instrumental in scaling and commercializing technology that will make inroads toward reducing our global carbon footprint.

Learning from successes

As with any technical advancement, we must continue to learn from what has come before us. As U.K. cluster projects approach final investment decisions (FID) and we continue to scale-up DAC and hydrogen hubs in the U.S., there's optimism for accelerated growth in CCUS deployment.

The hope is that as technology develops and deploys, the overall cost of decarbonization solutions will be reduced. Part of what we will learn from successful projects is how to make carbon capture work economically. The projects we are doing to advance CCUS with the U.K. clusters and North American hubs are prime examples of success stories that can be replicated across the globe.

Net Zero Teesside (NZT) Power is a prime example of this. In partnership with the Northern Endurance Partnership, NZT Power aims to be one of the world’s first commercial scale gas-fired power stations with carbon capture. The scheme could generate up to 860 megawatts of flexible, dispatchable, low-carbon power equivalent to the average electricity requirements of around 1.3 million U.K. homes. Wood has been engaged to support from an integrated project management standpoint for this pioneering carbon capture project. Onboarding a host of experienced and knowledgeable industry partners will be key to ensuring the sustainability of this project and facilitating industrywide learnings for years to come.

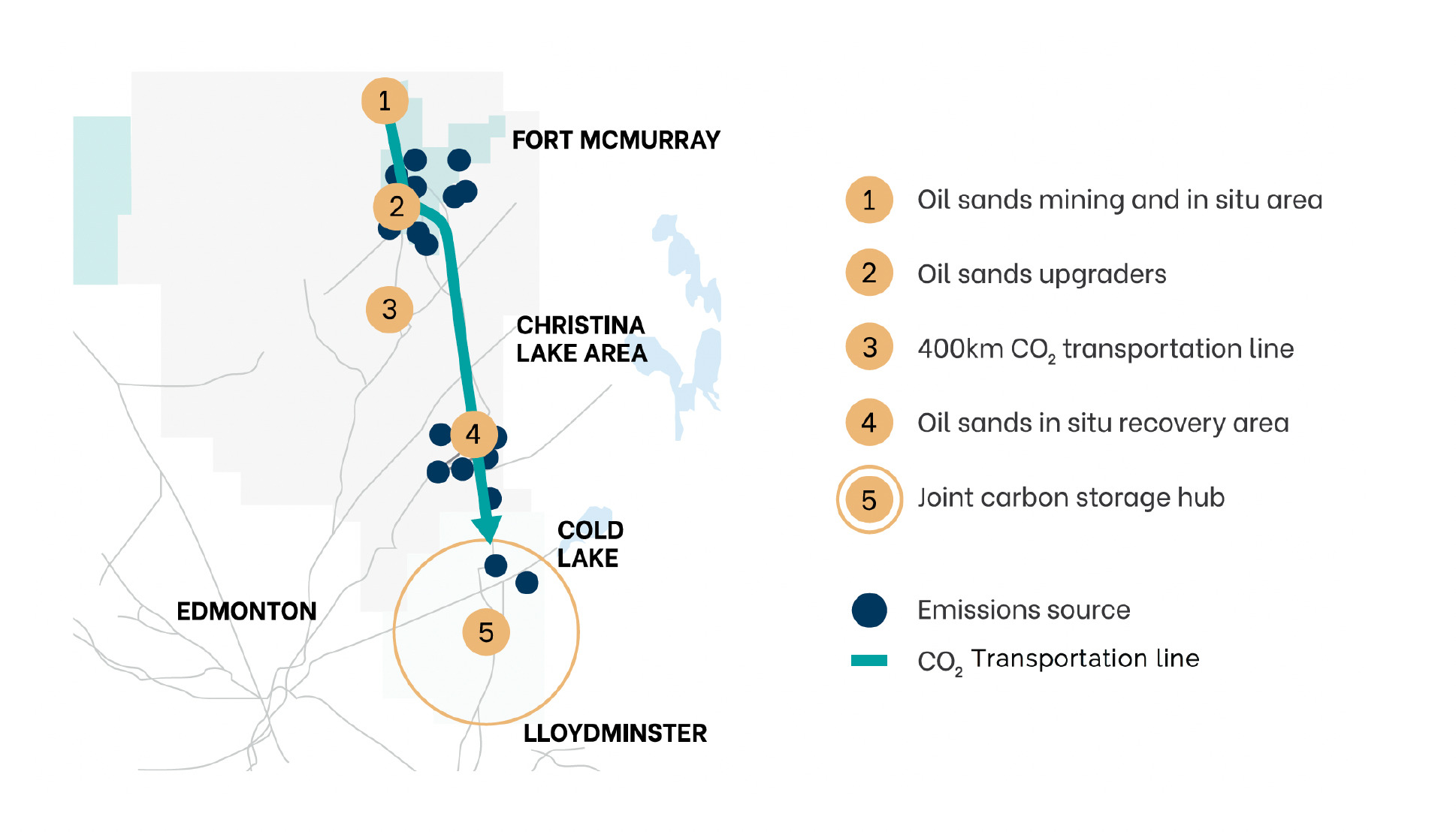

About 97% of Canada’s proven oil reserves are from oil sands, so decarbonizing oil sands production is vital. In addition to carbon capture at the oil sands, the transport of CO2 is critical to the success of the decarbonization effort. Wood is designing the CO2 pipeline system to transport CO2 captured by Canada’s six largest oil sands producers. Determining the correct CO2 pipeline specification can greatly impact the viability of pipeline networks that will cover hundreds of miles and need to operate safely and reliably for decades to come.

Similar to the projects in the U.K. and Canada, Wood is working on hub projects along the U.S. Gulf Coast to capture CO2 from multiple industrial emitters across multiple sectors. Ensuring that the pipeline system will operate as intended with varying compositions and contaminants at different flow rates requires a lot of engineering. Understanding the varying permitting requirements along pipeline routes adds additional complexity as well.

Maintaining momentum

Industrial decarbonization requires collaboration and problem-solving across multiple sectors and disciplines. Technical, economic and policy aspects of projects will have to align to deploy commercial solutions at scale. Lessons learned from both successful and failed projects and initiatives will be instrumental as we continue to decarbonize industry globally.

CCUS is on an upward trajectory. As one of the leading technologies for enabling large-scale decarbonization, it is important that we do everything in our power to safeguard this trend.

While government incentives have had a positive effect on the uptick in project development, incentives alone will not ensure sustainability. Engaging the market on the role of CCUS, the different variations and how to effectively design CO2 transport systems will be essential in ensuring its adoption and longevity. In our experience, there isn’t a “one size fits all” approach to CCUS. What determines success is designing a decarbonization strategy that is specific to a company’s carbon reduction goals and asset portfolios.

Recommended Reading

Energy Sector Sees Dramatic Increase in Private Equity Funding

2024-11-21 - In a 10-day period, private equity firms announced almost $20 billion in energy funding. Is an end in sight for the fossil fuel capital drought?

Quantum’s VanLoh: New ‘Wave’ of Private Equity Investment Unlikely

2024-10-10 - Private equity titan Wil VanLoh, founder of Quantum Capital Group, shares his perspective on the dearth of oil and gas exploration, family office and private equity funding limitations and where M&A is headed next.

Companies Take Advantage of ABSs to Finance Acquisitions

2024-10-17 - Some companies have taken advantage of asset-backed securitizations to monetize some of their cash flows and better position themselves for a sale.

Raising Capital When Private Equity Has Seen Better Days

2024-10-17 - Oil and gas private equity firms remain active in the market though fundraising hit its peak in 2017.

Private Equity Gears Up for Big Opportunities

2024-10-04 - The private equity sector is having a moment in the upstream space.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.