Ohio’s new No. 1 oil producer, Encino Energy, refrained from talking about its success until now. “We knew no one was going to believe the hypothesis was proven until it had been proven—and it’s proven now,” Ray Walker, COO, told Oil and Gas Investor in mid-June.

“So, I think it’s time Utica oil has its due.”

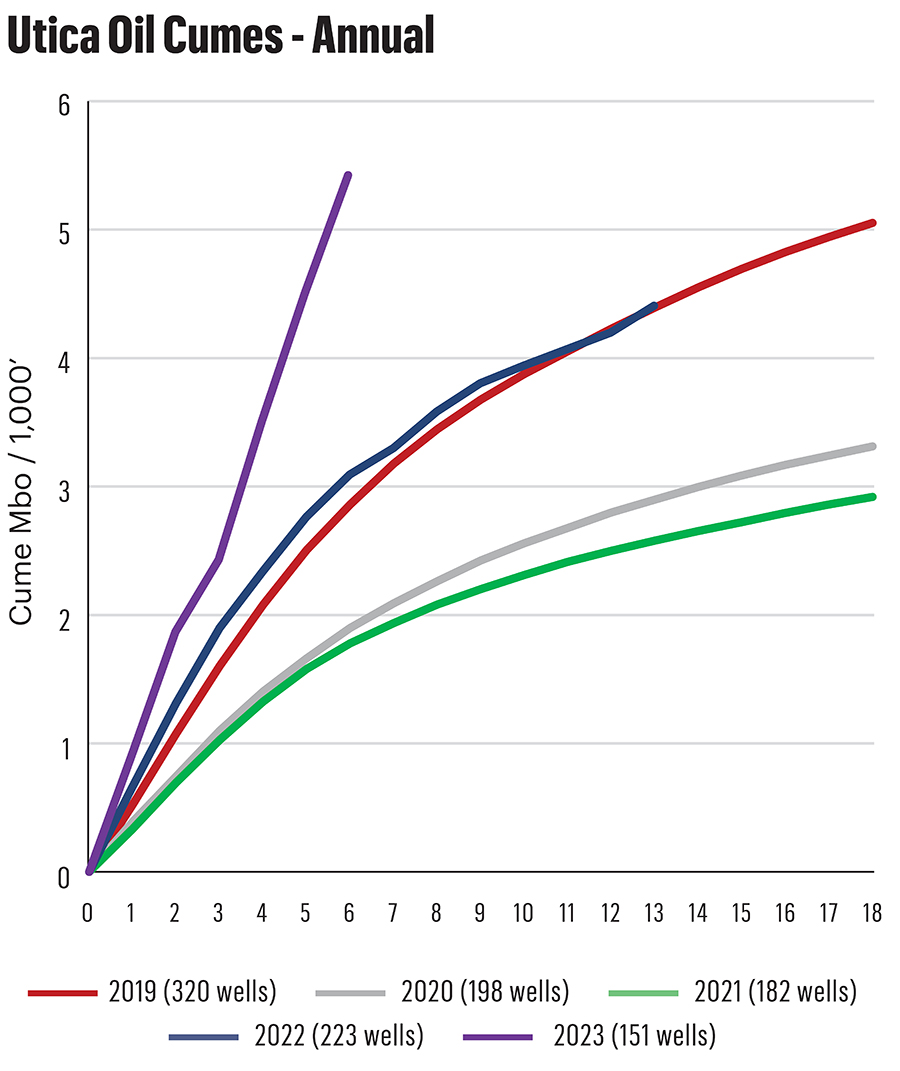

Six-month production from operators’ 151 new Utica oil wells in 2023 grew to more than 5,000 bbl/1,000 lateral ft from some 3,000 bbl in 2022 and 2,000 bbl in 2020 and 2021, according to J.P. Morgan Securities, citing Enverus data.

Recognition of the Late Ordovician-age Utica’s oil fairway has been more than a decade in the making, impeded by market forces rather than lithology and resource in place.

In the summer of 2011, Chesapeake Energy revealed it had put six horizontals and nine verticals in the rock, confirming nearly two years of industry rumors that it had been leasing.

It built the largest Utica position in the state: 1.25 million net acres.

And it projected the package could be worth between $15 billion and $20 billion.

It had five rigs drilling the rock and planned to increase that to eight by year-end, to 20 by year-end 2012 and to potentially as many as 40 by year-end 2014.

WTI was $90 at the time and reached $108 in the summer of 2014.

Well control

Chesapeake had pulled 3,200 ft of core and looked at more than 2,000 logs through the formation.

There was plenty of well control. Drilling in Ohio specifically for oil began in 1859 in Trumbull County a few months after the Drake well was made in Pennsylvania and launched what became the global oil industry.

(In 1814, the shallow Thorla-McKee well was drilled in Noble County with the intention of extracting salt. It produced salt, but it also produced oil, which the well’s partners bottled and sold as a topical medicine: “Seneca Oil.”)

(John D. Rockefeller, 20 years old in 1859, formed a transportation company that year in Cleveland and Standard Oil in 1870.)

And oil is found where it’s been found before: In 1884, a discovery in the Trenton Limestone, which underlies the Utica, set off a boom in the state, lasting 20 years and culminating between 1895 and 1903 with Ohio ranking as the No. 1 U.S. oil producer.

In 1896, the state made a then-record 23 MMbbl or 63,000 bbl/d, according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (DNR).

Another 78,000 wells were made by the early 2000s in the Early Silurian-age Clinton Sandstone that overlies the Utica.

By 2011, there were logs of more than 220,000 productive verticals throughout the state and some 60,000 were still producing, according to the DNR.

Also by then, Ohio drillers had made more than 1 Bbbl and 9 Tcf from 69 counties and 30 formations—mostly limestone, dolomite and sandstone—ranging from Pennsylvanian to Cambrian at between 50 and 10,300 feet.

‘Uticulous’

When Chesapeake announced its Utica oil play in 2011, research analyst Michael Bodino, who is now with the investment-banking group at Texas Capital, took a look.

He declared it “Uticulous.”

The first four horizontals each IP’ed more than 1,000 boe/d. “If the play wasn’t on your radar screen before this announcement, it definitely should be now,” Bodino reported.

By 2014, Chesapeake and others had landed 925 wells in the Utica.

But later that year, OPEC refused to pare its output, while Permian Basin shale was on a trajectory to what is 6 MMbbl/d today.

By early 2016, WTI was as low as $26/bbl, according to historical Energy Information Administration (EIA) data.

The Utica oil window’s associated gas’ economics had tanked, too, as the Marcellus—and then the Haynesville—overwhelmed U.S. gas demand. The price fell below $2/MMBtu in spring 2012 from as much as $13/MMBtu in 2008, according to the EIA.

Rigs were stacked. Ohio’s oil output fell from 73,000 bbl/d in 2015 to 55,000 bbl/d in 2017, according to the DNR. In 2021, it was 44,910 bbl/d.

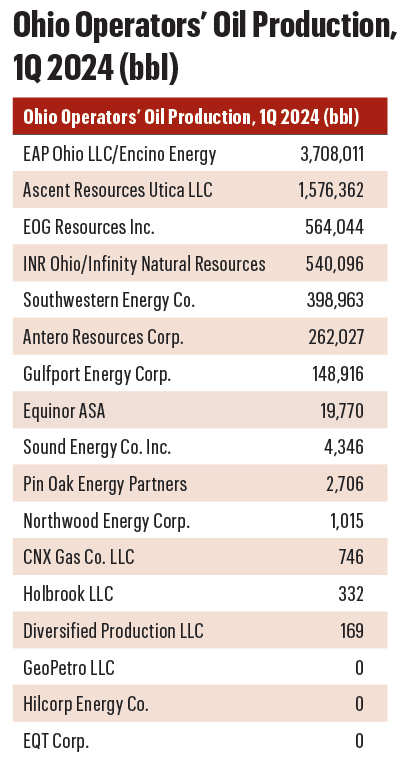

But the numbers have turned around in this decade. The state’s first-quarter 2024 oil production was 79,423 bbl/d as privately held Encino, Ascent Resources and Infinity Natural Resources picked up past operators’ fallow acreage and began making new holes.

Still, investors hadn’t been making much of what was underway, while the Permian was throwing shade on other Lower 48 oil plays and privately held E&Ps without Wall Street coverage dominated.

That was until November 2022: EOG Resources—famously choosy about where it will make new holes and typically spot on in its choices—confirmed that it had amassed 395,000 net acres in the Utica’s volatile oil and black oil windows.

Also, it acquired minerals under 135,000 acres.

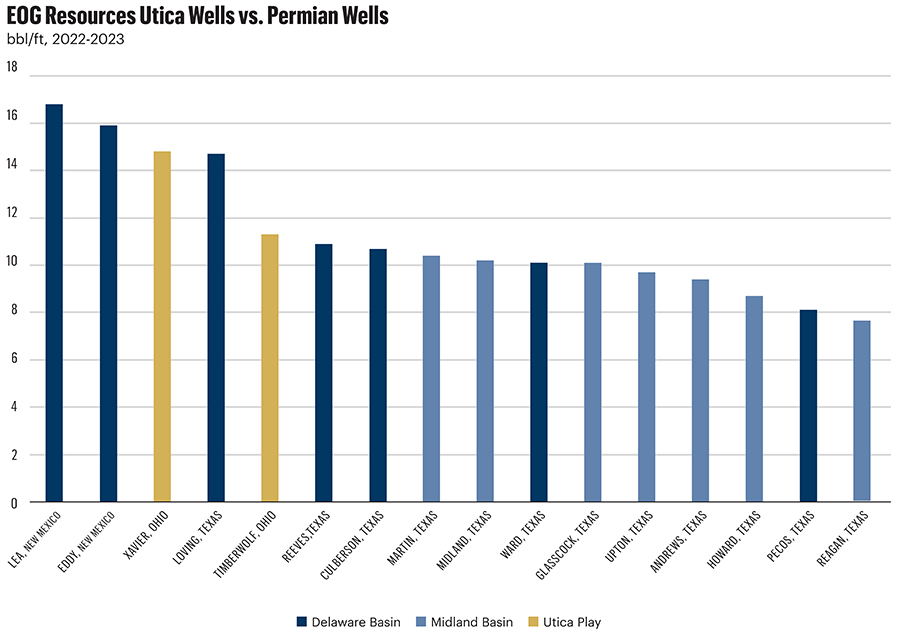

In May, it declared that the Utica oil window will “compete with the best plays in America” and wells are “very comparable to the Permian on a production-per-foot basis, both in oil and equivalent.”

Encino’s origin story

In the first quarter, Encino averaged 40,747 bbl/d, up from 19,765 bbl/d in 2020.

The company’s Ohio oil story began in 2018.

Ray Walker was retiring from Range Resources, where he was COO, when he got a call from his old boss, John Pinkerton, Encino’s executive chairman.

Encino had been founded in 2011 by Hardy Murchison, who had worked on portfolio investments at First Reserve and began his career as an energy investment banker. Murchison had worked for Pinkerton in the 1990s.

“Until about 2016,” Walker said, “Encino had focused on smaller acquisitions, mineral interests, small things.”

Pinkerton began his career with Range via a predecessor in 1980, long before shale development. Over the years, he had worked the Appalachian Basin’s conventional oil and gas fields of Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Virginia.

And Range eventually accumulated 1.7 million net acres.

In 2004, it drilled an initial Marcellus well and launched full-field horizontal development in 2007. By then, Pinkerton was Range’s president and CEO.

Walker had joined in 2006, opening the Pennsylvania office that would be headquarters for the Marcellus, which eventually became Range’s entire portfolio.

Since Murchison had been at Range before Walker, they hadn’t met, “but John was sort of the bridge,” Walker said.

Pinkerton resigned from the Range board in the spring of 2016 to join Murchison at Encino, taking the executive chairman position. They began looking at large asset packages other operators might sell. Not only was WTI just crawling out of a $26 low, gas was still below $2.

“These companies had multiple assets in different basins that were going to be challenged,” Walker said.

Pinkerton and Murchison settled in on one particular target—one Pinkerton knew well and that both he and Murchison had worked in their time at Range many years before: Ohio oil.

Pinkerton had drilled through the Utica plenty of times in his earlier career, putting verticals in the Trenton Limestone. Some 16,000 wells targeted that formation through the early 2000s, according to Bernstein Research.

Chesapeake still had a large footprint of HBP’ed property in the volatile oil window. Its Utica oil production had declined in 2017 to 10,000 bbl/d, according to an annual report.

The behemoth investor Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPP Investments) liked the look of it, too. In June 2017, it showed up with a $1 billion commitment, forming Encino Acquisition Partners (EAP) for 98% interest. The Encino Energy team committed an additional $25 million.

“The Canada Pension Plan was key to the story,” Walker said. “They were really attracted to the fact that John and Hardy had a big idea.”

Encino signed a deal for the Chesapeake property in July 2018 for $2 billion. Walker rejoined Pinkerton in September. The deal closed in October.

“When we took over the Chesapeake asset, it was about 900,000 net acres and about 600 MMcfe/d from about 900 operated wells, all horizontal,” Walker said. The leasehold was 85% HBP.

Today, Encino has 1.1 million net acres and 1,000 wells, making 40,747 bbl/d of oil and 936 MMcf/d of associated gas and NGL. Its acreage is 95% HBP.

Oil and NGL make up about 40% of the mix, “but about two-thirds of our revenue is oil and NGL. Liquids are worth so much more than gas,” Walker said.

In this past first quarter, Encino produced 3.7 MMbbl of oil, averaging 40,747 bbl/d. Its 2023 oil production was 13.9 MMbbl, averaging 38,019 bbl/d.

It’s running four rigs and two completion crews—the most among all operators in Appalachia, including those drilling the Marcellus in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, as of mid-June, according to Enverus data.

“We’re the most active operator in Appalachia now and we’re enjoying that,” Walker said.

Modern completion

As Chesapeake was putting its leasehold together, it also put together firm transportation (FT) and minimum-volume commitments (MVC) for the takeaway.

The takeaway is ample. The late Aubrey McClendon, Chesapeake’s co-founder, “did a lot of good things,” Walker said, “but one of the good things he did here is he went really big."

“He leased a bunch of land. He came in with a bang, drilled a bunch of wells and bought a ton of FT very early on.”

When Encino took over the asset in late 2018, it went to work on, at least, raising production to meet the FT and MVCs, which the property was underwater on. “It took us about a year to get things back in shape,” Walker said.

And then COVID happened. WTI fell from a New Year’s start of $60/bbl to about $40. In a trading anomaly, it closed at a negative $37 on April 20, 2020.

Natural gas demand fell, too: The price was $1.42/MMBtu and tankers of U.S. LNG were at sea without orders.

In 2021, though, WTI improved to $70.

“We started in earnest on the oil play because we knew there was a lot of potential there that was untapped,” Walker said. Despite a decade of work by then, “people didn’t know how to get it out.”

While the dolomitic Middle Bakken oil play had been underway for more than a decade by 2011, it had two frac barriers: the Upper and Lower Bakken shales. Meanwhile, making economic wells in the Permian’s oily tight rock had only just begun.

There wasn’t a recipe for how to make an economically successful, stimulated, horizontal Ohio oil well, specifically.

Encino reentered a few Chesapeake Utica oil wells with a modern completion. But, with plenty of new-drill opportunities in its leasehold, “it’s hard to justify [recompletions],” Walker said.

“It’s just cheaper to go drill new wells and it’s a better use of our capital.”

CPP Adds $300MM

The new-drills are making headlines. Five wells on one Encino pad, the Burdette in Harrison County, took all Top Five spots in Ohio’s first-quarter oil-production ranking.

Burdette was brought online Dec. 1. In its first four months, it produced 740,162 or 1,213 bbl/d of oil per well.

Meanwhile, Encino’s Oliver pad’s four wells in Carroll County produced 450,281 bbl in their first 91 days of full production.

In Columbiana County, Encino returned to the 2012 vintage one-well Sanor Farms pad in 2023 with four new-drills, producing 421,903 bbl combined in their first 184 days online.

In April, CPP invested another $300 million in Encino toward accelerating development.

The investment horizon is long. A private-equity fund typically aims to monetize an investment within seven years; a pension plan seeks returns from harvesting in situ—via dividends.

“They’re very long-term focused,” Walker noted. “And they focus a lot on [asset] sustainability, low risk and good, solid returns.”

At Encino’s current four-rig count, it has 10 years of core inventory—what works at $40 and $50 oil. It is continuing to lease. “And we’re filling in holes in what we already have. But we’re not looking to just buy somebody.”

Infinity Natural Resources

Zack Arnold was among Chesapeake team members who drilled those Utica wells in the 2010s.

A petroleum engineering grad of Ohio’s Marietta College, Arnold and four colleagues from his Chesapeake and Northeast Natural Energy days formed Infinity Natural Resources in 2017 with private equity from Pearl Energy Investments and NGP.

Based in Morgantown, West Virgina, the group—all career Appalachian drillers—kicked off by putting horizontals in the Marcellus in Pennsylvania.

In 2021, it went to work in Ohio, picking up a package in Carroll County from PennEnergy Resources for $32 million.

And, like Encino, Infinity came for the oil.

“We focused on well returns,” Arnold, Infinity president and CEO, said. “In Ohio, that points you to the volatile oil fairway. If you’re in a dry-gas or a wet-gas environment, your single-well economics are more challenged.”

His and colleagues’ familiarity with Ohio’s Utica “gave us a bit more confidence in understanding how the rock would perform with modern techniques—the right fluids, sand loadings, landings and, then, longer laterals, of course,” he said.

“We were confident that modern completion optimization would result in our wells outperforming the historical dataset.”

The past demise of the Utica oil play wasn’t because of the rock. “Each operator had its own focus.”

Sometimes the priority was to fulfill MVCs. “Sometimes they spent the least amount of capex possible because they were having financial problems. Sometimes they were seeking gas; sometimes they were seeking oil.

“So, each of these operators had their own drivers.”

All the data was there. “But it was kind of cloudy as to what anybody had done at any point in time and why they did it,” he said.

Except for Chesapeake, that is. Because Arnold had worked on many of those Utica oil wells, “I got to see a lot of what they did and I understood some of the context.”

Perry pad

Upon closing the PennEnergy deal, Infinity picked up a rig and drilled three Perry pad wells in Carroll County, bringing them online in November 2021.

“We really liked the return profile and were excited to confirm our view of the play,” Arnold said. “We recognized quickly what EOG has now said out loud: These are high-quality oil wells.”

The three Perry wells’ first-36-day average was 628 bbl/d each and production through this past March 31 totaled 520,414 bbl, or 202 bbl/d each, in their first 28 months, according to the DNR file.

First-quarter production was 80 bbl/d from each.

From its anchor position in Carroll County, Infinity began bolt-on leasing. In October, it added Utica Resource Operating’s portfolio, gaining 49 wells, all producing oil and 39 of them in Guernsey County. The price is undisclosed.

Among the adds is the two-well Stillion pad in Guernsey County that Utica Resources brought online in April 2023. First-361-day production was 341,200 combined or 473 bbl/d per well, according to DNR data.

Adding the portfolio to its own, Infinity held the No. 4 rank in first-quarter 2024 oil production, overcome by EOG, which had three pads for a total of 11 new wells online before quarter-end and rising to the No. 3 position.

To further add to its Guernsey position, Infinity won a bid earlier this year to drill under Ohio’s Salt Fork State Park, picking up 5,705 net acres.

It now has 60,000 net acres in Ohio and 30,000 net in Pennsylvania.

Its Ohio oil output on June 30 was some 14,500 bbl/d gross and 10,000 bbl/d net from 111 operated horizontal wells.

It’s looking to continue to add leasehold.

The frac recipe

Operators are landing in the porosity-enhanced dolomitic Point Pleasant member of the Utica Formation. (The Ohio Supreme Court sent a lease dispute back to a lower court recently that questioned whether leasing the Utica includes rights to the underlying Point Pleasant.)

Like Chesapeake had estimated in 2011, Encino’s Walker said the Utica compares more to the Eagle Ford than it does the Permian’s Wolfcamp in reservoir characteristics. The formation has no water, he added.

“The only water that we produce out of these wells is what we put in them. That’s an added advantage to the economics: We don’t have a lot of produced water to get rid of,” Walker said.

In comparison with the Marcellus, Infinity’s Arnold said, “the TOC [total organic carbon] of the Marcellus tends to be higher, near 6%, and the Utica tends to be closer to 4%.”

Typically, Infinity pumps about 2,200 pounds of sand per foot in the Utica.

“We’re doing a very similar job as most of our neighbors. I think we all have non-op positions in each other’s wells in Ohio once you get a meaningful scale,” Arnold said.

The frac formula is consistently similar when moving north and south, east and west, he added. “Each operator probably has its own flavor, but I don’t think there’s a widely variable design at this point in the volatile oil window.”

Any change in the formula is more likely to come from whether it’s completing wells at 700-ft spacing or 900-ft spacing. “Or are we co-developing?” Arnold said. “Those philosophies are going to drive our recipe much more than which county we’re in.”

The Bauer pad

Meanwhile, Encino is keeping its current D&C recipe tight but Walker said the formula will vary from well to well.

At its Bauer pad in Carroll County, the five wells were completed with 2,225 pounds of sand and 70 bbl of slickwater per foot in stages some 200 feet apart. Spacing was 800 feet.

Lateral length averaged 18,600 feet. The wells made 1.68 MMbbl through March 31 since coming online in July of 2022, according to the DNR.

One of the wells had a first-30-day IP of 1,948 bbl/d. Reserves are 875,000 bbl per well or 47 bbl/ft. Cost was $650 per lateral foot.

Encino’s IRR at $60 oil and $3 gas is 84%. Drilling averaged 2,100 ft/d.

Wells on the pad prior to Encino taking over the lease had been completed with 1,812 pounds and 27 bbl/foot. The fluid was gel. They averaged 9,400 ft in lateral length.

Spacing was 1,000 ft for four wells. The cost was $900/lateral foot. Reserves were 367,000 bbl per well or 39 bbl/ft.

The IRR was 5% at $60 oil and $3 natural gas. Drilling averaged 1,500 ft/d.

“We’re not necessarily focused on making the most production or the biggest barrels per foot or even getting the lowest cost per foot,” Walker said. “We’re truly focused on the best economics rather than just looking at the oil rate for the first 12 months.”

Big IPs make headlines, “but if you spent too much money, it was a bad economic decision.”

More than 200 wells into the oil play now, Encino’s results are “still getting better,” he added. “We’re probably in the fourth inning of a baseball game from an optimization standpoint.

“There’s a lot more we want to do. It just takes time.”

Geologically quiet

The Utica is mostly homogenous across the oil window in contrast to some other oil plays, but there are variations, particularly when moving west.

Walker said, “It’s a gradual change from the [far eastern] dry-gas side of the field to the [far western] black oil side of the field. You’re changing depth.”

But the formation is quiet. “There’s not a lot of structural complexity. There’s not a lot of geohazard.” Wells are landed in a 10 ft- to 15-ft window.

Arnold said the Utica oil fairway is an easier drill than Infinity’s Marcellus wells in Pennsylvania—again, because the Utica fairway is geologically quiet.

“We can do very long laterals with very few changes to our directional plan.”

Infinity TD’ed a 14,000-footer in mid-June that stayed in the 3.5-ft zone the entire time.

“That’s hard to do in some areas of the Marcellus because you have more complexity and you have to chase that formation a little bit more,” Arnold said. “We don’t have to do that in Ohio.”

Still, the difference isn’t meaningful. “It just might save you a day on rig time.”

That particular well is on a pad that had four existing wells. “It’s what we do right now—return to pads that have some development on them,” Arnold said.

Infinity’s optimal lateral is between 14,000 ft and 20,000 ft.

At Encino, Walker said, “We’re routinely drilling 4-mile laterals now.”

Its average lateral length this year will likely be 17,000 ft, plus or minus. “Some 14,000 and some 22,000. But we try to shoot for around 18,000, just from a design standpoint,” he said.

Enter EOG

In May, EOG declared the Utica’s volatile oil window can “compete with the best plays in America.”

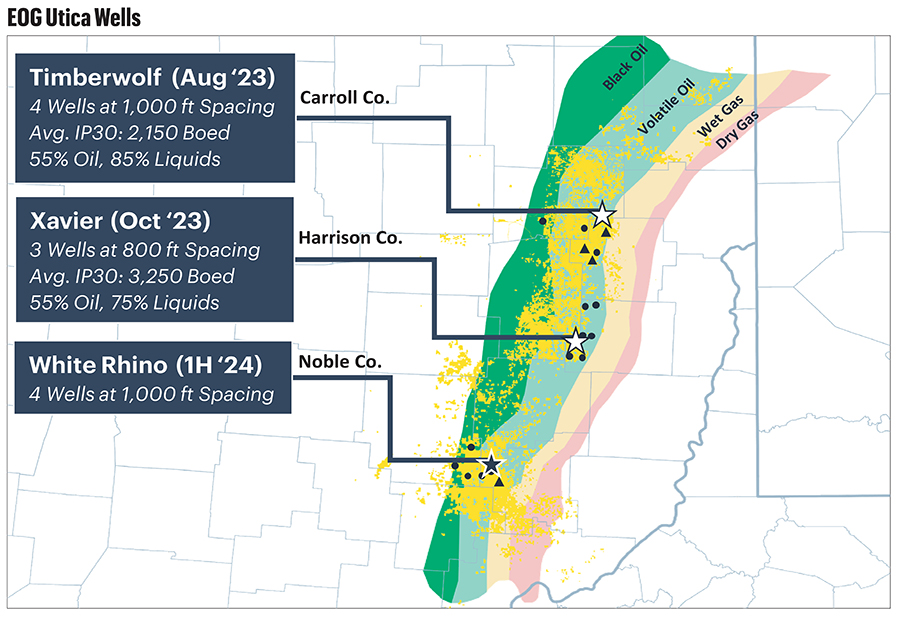

It now has 435,000 net acres, acquired for an average of $600 an acre—all in the volatile-oil and adjacent black-oil fairways 140 miles north to south.

It owns the minerals under 135,000 acres, blocked up in the south, for $1,800 an acre. There, it has 100% net revenue interest, “which makes those 135,000 acres extremely attractive,” EOG COO Jeff Leitzell said at a J.P. Morgan Securities conference in June.

The leasehold and minerals were bought in 2022 from Encino and Artex Energy Group for $500 million, according to J.P. Morgan Securities, citing Enverus. It came with 18 legacy wells.

Walker said the attention EOG has brought has given validation to the oil window’s economics. When the play had its first start in 2011, it “was kind of the last one and it was in the shadow of all those other big oil plays [in the Permian, Bakken and Eagle Ford].

“So, it got a bad rap upfront.”

Like Encino, Infinity had been working on the down low. With EOG’s entry and Infinity’s recent state lease win, “we’ve lost anonymity,” Arnold said. “A lot of people ask us what’s going on.”

EOG has brought “a credibility to the play that it hasn’t really had outside of Ohio over the last several years,” he said. “EOG brought a legitimacy and a focus the play deserves and the operators in the play deserve as well.”

Raising capital, such as last fall to buy Utica Resources, was “a little bit easier than before as our investors saw the results we were generating in the play,” he said.

EOG’s wells

EOG had one rig drilling the play in early July. At the June conference, Leitzell noted, in telling the back story on its initial look at the Utica, that U.S. oil-producing basins are well understood at this point of the industry’s 165 years.

But many have been drilled with old technology and recipes—including technology as young as just 10 years. “Technology has evolved so much that you can go in … and you can get just absolutely outstanding returns,” Leitzell said.

Initially, EOG drilled four delineation wells to test performance with new tech and to identify the formation’s structural features.

Its findings were similar to Encino’s and Infinity’s: The target zone is consistent, allowing for a precise landing at the most productive depth, even with extra-long laterals.

Since then, it’s put three multi-well pads online: Timberwolf, Xavier and White Rhino.

In Harrison County, the three-well Xavier made 667,366 bbl in its first 179 days online, averaging 1,243 bbl/d each. First-88-day production was 1,536 bbl/d each.

The IP-30 production mix was 55% oil, 75% liquids, according to EOG.

In Carroll County, its four-well Timberwolf pad came on in the third quarter and made 780,068 bbl through first-quarter’s end, averaging 886 bbl/d per well in their first 220 days. First-37-day production averaged 1,214 bbl/d per well.

Its newly online four-well White Rhino in Noble County made 30,800 bbl in its first eight days, averaging 963 bbl/d per well.

The Xavier wells were placed at 800-ft spacing; Timberwolf and White Rhino, 1,000-ft. The wells are 3-mile laterals.

‘Comparable to the Permian’

EOG’s Xavier and Timberwolf wells are comparable to Permian wells’ bbl/ft, the company told investors in May.

Xavier’s first-six-month bbl/ft is 14.8/well. When including NGL and natural gas, it’s 25.1 boe/ft. At Timberwolf, the average is 11.3 bbl/ft and 20.3 boe/ft.

Timberwolf and Xavier “are fantastic,” Ezra Yacob, EOG chairman and CEO, told investors. “They’re exceeding what we initially had in our type curves and they’re more than confirming some of our early thoughts on spacing.”

Keith Trasko, EOG’s senior vice president of E&P, said, “We see that these compete with the best plays in America—very comparable to the Permian on a production-per-foot basis, both in oil and equivalent.”

Yacob added that the Utica “will be competitive with the premier unconventional plays across North America.”

EOG plans 20 net wells in the Utica this year throughout the volatile-oil window, north to south. Its Ohio leasehold is more than 90% HBP.

Not quite Midland

Piper Sandler securities analyst Mark Lear reported in June that, so far, “the Utica oil window is close but still not on par with Midland [Basin] oil productivity.”

Noble and Guernsey counties—the southern part of the Utica volatile oil fairway—produced better cumulative oil than the northern fairway, he added, and EOG’s minerals ownership in its leasehold there should boost returns.

“While difficult to compare with Permian well productivity, the basin does benefit from a lower royalty regime, the ability to drill extended laterals of up to 4 miles and significantly less produced formation water …,” Lear reported.

He estimates EOG’s returns in the oil fairway in the 50% range at $70 oil and $3.50 gas based on 15-month payback and D&C of $1,150 per lateral foot.

Private operators are making wells for $750/ft, he added.

The black-oil phase

When Chesapeake announced its Utica oil discovery in 2011, it noted that the rock has four phases, west to east: black oil, volatile oil, wet gas and dry gas.

It likened the phase changes to those in the Eagle Ford, “but economically superior,” it reported.

In the Utica’s black oil window, EOG plans to shoot seismic before beginning delineation. “It does shallow up a little bit,” Leitzell said in June. “But it is also just as thick and it looks like very, very good rock.”

The lower thermal maturity of the black-oil phase will mean less pressure, which typically “reduces the well productivity a little bit,” Yacob said in May.

“But it also reduces costs. So, your economics are still really comparable to all the other portions of the play.”

That the window hasn’t been developed yet is a result of efforts in the past decade that focused on the volatile oil and wet-gas fairways, Infinity’s Arnold said. “People were doing things that they needed to do for other reasons.”

But nothing suggests the black oil window won’t work, he added.

“I haven’t seen anything that makes me call that we found the western boundary of economics. We’ll sit back and watch. We’re excited to see what they do [at EOG].”

A ‘pro-business’ state

“The operating environment in Ohio is constructive for oil and gas development,” Arnold said. “There’s a clear permitting and regulatory process, which guides how to operate, how to get permits, how to function.”

The state also implemented unitization in 2019. That has helped in consolidating and extending operators’ acreage positions, Arnold said.

Like in Texas, for example, Ohio’s rules make sure mineral owners can develop their resources, while also assuring the resources aren’t wasted.

“It’s a strength of Ohio,” Arnold said. “The regulatory environment in Ohio is clear. That puts us in a position to operate with clarity, which is what every operator wants.”

Encino’s Walker said that, in Ohio, “people are extremely pro-business.

“Ohio is probably closer to Louisiana, Texas and Oklahoma [in sentiment toward oil and gas],” he said.

The attitude in Ohio is “‘Let’s figure out how to do this correctly.’ It’s not immediately ‘We can’t do it’ or ‘Let’s figure out how to not do this at all’ like in some other states.”

‘The right guardrails’

The rules make sense, Arnold added. When Infinity begins drilling under Salt Fork State Park, “you won’t know we’re there because we’re not permitted to operate in the park.”

The vertical hole will be made outside the park’s perimeter. The deal also requires water-quality testing and restricted drilling times.

Drilling, completion and other oilfield equipment are largely prohibited from traveling through the park. Light pollution is to be mitigated.

“The state’s done a good job of making sure the operators have the right guardrails so their lands are protected, while we’ll also be able to develop their resources,” Arnold said.

State parks are operated by the DNR. In February, Infinity won the 5,705 Salt Fork acres for $10,250 an acre, totaling $58.5 million.

The royalty is the standard 12.5%. Infinity sweetened its offer with an additional 7.5%.

Separately, Encino placed the high bid, $3,500 an acre, on 302.3 acres in Valley Run Wildlife Area for $1.1 million along with the 12.5% royalty and an extra 5.5%. It also won 66.2 acres in Zepernick Wildlife Area for $3,500 an acre, totaling $231,700, and also with an extra 5.5% for a total royalty of 18%.

An example of the state’s support for oil and gas production: In 2022, it declared natural gas a green energy.

“It doubles down on where the state’s elected officials are,” Rob Brundrett, president of the Ohio Oil & Gas Association, said at Hart Energy’s DUG Appalachia conference in November.

He estimated energy investments during the past decade have been more than $100 billion.

“And [most of] that money is going into eastern Ohio,” Brundrett said. “I can’t overstate the importance of that kind of … investment in, really, one of the poorest regions in our state.”

The last oil frontier

Walker views Ohio as the Lower 48’s last oil frontier—one that works at sustainable oil prices. More formations could work at higher oil prices, but $150-oil doesn’t last long; demand shrinks.

Ohio oil works at current oil prices, he said.

Consolidation in other oil basins is as operators are looking for more well inventory. Ohio’s oil window, on the other hand, is in just the beginning of its modern development.

“All the other big oil plays are completely leased up,” Walker said. “There’s just not a lot of opportunity for people to grab inventory anywhere else.”

Walker’s oil and gas career began in 1975, working summers and winters as a roughneck to pay his way through engineering undergrad studies at Texas A&M.

Is Utica oil easy in comparison with all the other fields he’s worked in his 49-year career?

Utica oil “feels pretty easy,” he said. “But I’m also a lot smarter and wiser than I used to be. So, I don’t know.”

Modern equipment and technology do “make it seem a lot easier. I don’t remember many times in my career where I’ve done over 200 wells as fast as we’ve done them and not had some kind of failure.”

In the Cotton Valley in the 1990s while he was with Union Pacific Resources, Walker and others screened out in those years, for example. “We don’t do that very often anymore,” he said.

His first Marcellus well after joining Range in 2006 took 30 days to drill and it was a 3,000-ft lateral.

“Now we’re drilling 18,000 feet in 72 hours. It’s hard to even compare how far we’ve come—and even just in the last 10 years.”

And today, after drilling an 18,000-ft lateral in three days, the rig lifts itself, walks a few feet over and makes the next hole.

Recommended Reading

Crescent Energy Closes $905MM Acquisition in Central Eagle Ford

2025-01-31 - Crescent Energy’s cash-and-stock acquisition of Carnelian Energy Capital Management-backed Ridgemar Energy includes potential contingency payments of up to $170 million through 2027.

Petro-Victory Buys Oil Fields in Brazil’s Potiguar Basin

2025-02-10 - Petro-Victory Energy is growing its footprint in Brazil’s onshore Potiguar Basin with 13 new blocks, the company said Feb. 10.

Apollo Funds Acquires NatGas Treatment Provider Bold Production Services

2025-02-12 - Funds managed by Apollo Global Management Inc. have acquired a majority interest in Bold Production Services LLC, a provider of natural gas treatment solutions.

Report: Diamondback in Talks to Buy Double Eagle IV for ~$5B

2025-02-14 - Diamondback Energy is reportedly in talks to potentially buy fellow Permian producer Double Eagle IV. A deal could be valued at over $5 billion.

VAALCO Acquires 70% Interest in Offshore Côte D’Ivoire Block

2025-03-03 - Vaalco Energy announced a farm-in of CI-705 Block offshore West Africa, which it will operate under the terms of an acquisition agreement.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.