BP finally dove more heavily into the U.S. shale game when it acquired the onshore assets of BHP in 2018 for $10.5 billion—its largest deal this century—formally launching the BPX Energy brand for the British supermajor.

What followed was a rapid race to save leaseholds, a trudge through pandemic-era price swings, the sale of non-core assets in Colorado, New Mexico, Wyoming and Oklahoma, and an infrastructure buildout in the BHP-purchased Permian Basin position.

Now, under the leadership of new CEO Kyle Koontz, BPX can finally focus on ramping up the volumes in its core basins in the West Texas Permian and South Texas Eagle Ford Shale. Activity will pick back up in the Haynesville Shale as soon as natural gas prices recover.

“There’s renewed purpose, and it’s shown in the numbers in the business,” Koontz said. “We’re ahead of schedule in our production growth plans, and it’s showing up big for BP.”

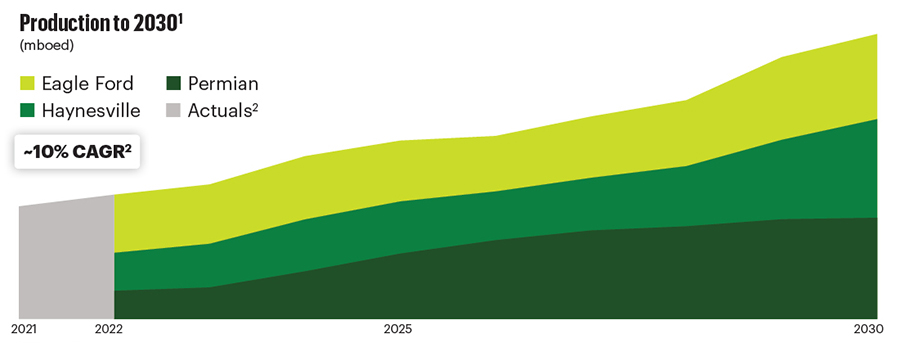

BPX’s production averaged 406,000 boe/d in fourth-quarter 2023, up 28% from 318,000 boe/d in the final quarter of 2022. The stated goal is to hit 650,000 boe/d by 2030, more than double the 2022 volumes. And BP is committing an average of $2.5 billion in annual capex to BPX from now through 2030, compared to $1.8 billion in 2022.

Koontz and Clark Edwards, BPX vice president and COO of development, spoke exclusively with E&P to discuss their field development plans in each of the three core basins.

“We love the portfolio. We’re kind of hitting our stride, so to speak. We’ve been mostly doing lease-obligation drilling for the last couple years, but we’re now in growth mode,” Koontz said during an interview at BPX’s Denver headquarters.

“I like the focused, concentrated position. I think it fits well with where we’re headed with BP focusing on just high-quality assets and then delivering on those assets. That’s kind of where BPX’s head is right now. I don’t see any big changes happening. I do think we are going to need to add inventory,” Koontz said. “Renewals of assets is always a strong part of the growth strategy, but one of the benefits of having the core position and the size of the BHP deal is we have the luxury of time. We’re not pressed to do anything, so we really want to make sure we buy right.”

Prior to the BHP deal in 2018, BP’s very gassy onshore U.S. production only churned out 5% crude oil. While it still skews gassier, BPX is leaning into liquids and aiming for a more balanced mix, especially in this current environment of weak gas prices.

The stronger emphasis on U.S. shale also coincides with parent BP more vocally embracing hydrocarbons again after emphasizing renewable energy.

“Oil and gas have always been the cornerstone of the strategy. I think we’ve learned some lessons, and we are now going to move at the pace of society, and we’re going to be pragmatic about it,” Koontz said. “BPX fits within that. It’s the resilient hydrocarbon strategy. Not only do we need to be profitable, but we need to be environmentally sensitive and conscious about how we impact the Earth and the communities around us.”

Overall strategies

BPX is currently running a nine-rig program with four each in the Permian and Eagle Ford and one in the Haynesville—with the ability to scale up as needed. A fifth rig in the Permian was recently eliminated because efficiency gains had led to equivalent well completions with fewer rigs.

“We basically want to run as few rigs as possible and get the same volume and profile,” Koontz said. “That’s not what our drilling partners want to hear, but that’s how we try to optimize the business.”

He said the goal is to drill as few wells as possible to drain the section.

“We typically try to up-space as much as we can for that reason. In the Eagle Ford and the Permian, there’s usually three to five wells per pad, and we’ll do a full pad at a time. In the Haynesville, it’s been a little bit more spread out because it was underdeveloped relative to the other assets. So, we had some catching up to do. We had to drill around the field to shore up all of our leases and finish all of our obligations. We’ll shift into next year, and it’ll be more multi-well per pad,” he said.

Edwards is helping lead the charge into the oilier portions of the Permian and Eagle Ford.

“We are dramatically increasing our liquids content through 2025 and 2026. Then, post-2026 and toward the latter part of the decade, the investment shifts a little bit back into more gas in the Haynesville if the strip holds,” Edwards said.

“Our opinion—and my opinion—is that we bought elite, top-tier acreage from BHP back in 2018. What you see right now is our strategy to go out and develop that acreage position and to really maximize on it,” he added. “We’ve been able to go in and organically develop those assets, and our growth profile continues to fit that strategy. We are planning to grow in a significant way through the bit.”

BPX is leaning on a mix of longer laterals, more intense zipper fracs and additional proprietary tools to maximize efficiencies and gain advantages, such as its RTAN system (rate-transient analytics for frac designs).

“It’s allowing us to better define the efficiency of our fracs and exactly how we are interacting with that SRV [stimulated reservoir volume], and what are the most efficient ways to complete these wells,” Edwards said. “You’re constantly solving for the efficiency of your frac and the efficiency of the economics of those wells. It’s not always the biggest well that creates the best value. Sometimes, a smaller, less expensive frac can be a more valuable well, and there’s tension there all the time. This proprietary suite of tools that we use allows us to solve that tension in a way that gives us a competitive advantage.”

The best advancement on the drilling side, according to Koontz, was the Drilling Automation Software (DAS) system developed by Exxon Mobil, which is licensed through Pason. Cycle times were reduced by 20% as a result, he said.

“It is primarily looking to solve for weight on bit,” Koontz said. “Our guys in the field may have had a mentorship-style experience that says we should put 45,000 pounds of weight on bit. But now they’re putting 80,000-plus because they’re setting boundary conditions, but they’re letting the algorithm—the smart drill—solve for what’s the best weight on bit.”

Edwards broke down some of the challenges by basin.

“In the Haynesville, you’re dealing with temperature and fairly weak rock. Those two things work against you because you’ve got high pressure, and you need heavy mud. And the heavy mud breaks down the rock. You’re kind of constantly in this tenuous balance between how do you solve for those things.

“In the Eagle Ford, it’s understanding how tight you can go on redevelopment spacing and how those parent-well fracs affect the area that you’re drilling. It’s really a question of lateral stability and how much mud weight you can apply to keep a stable lateral without breaking down something in the shallow part of the well.

“When you go to the Permian, the drilling process from a rock perspective is not the complication. The complication there is just some of the pressure that we’re seeing shallower in the wellbore, how we control that pressure and where that intermediate casing set point is. That is not something unique to BPX, and it’s something that we’re working on,” he said.

Permian plans

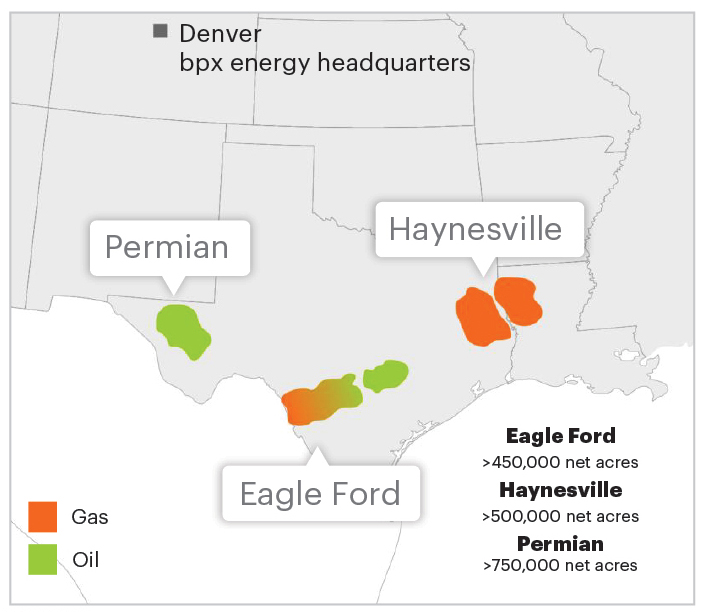

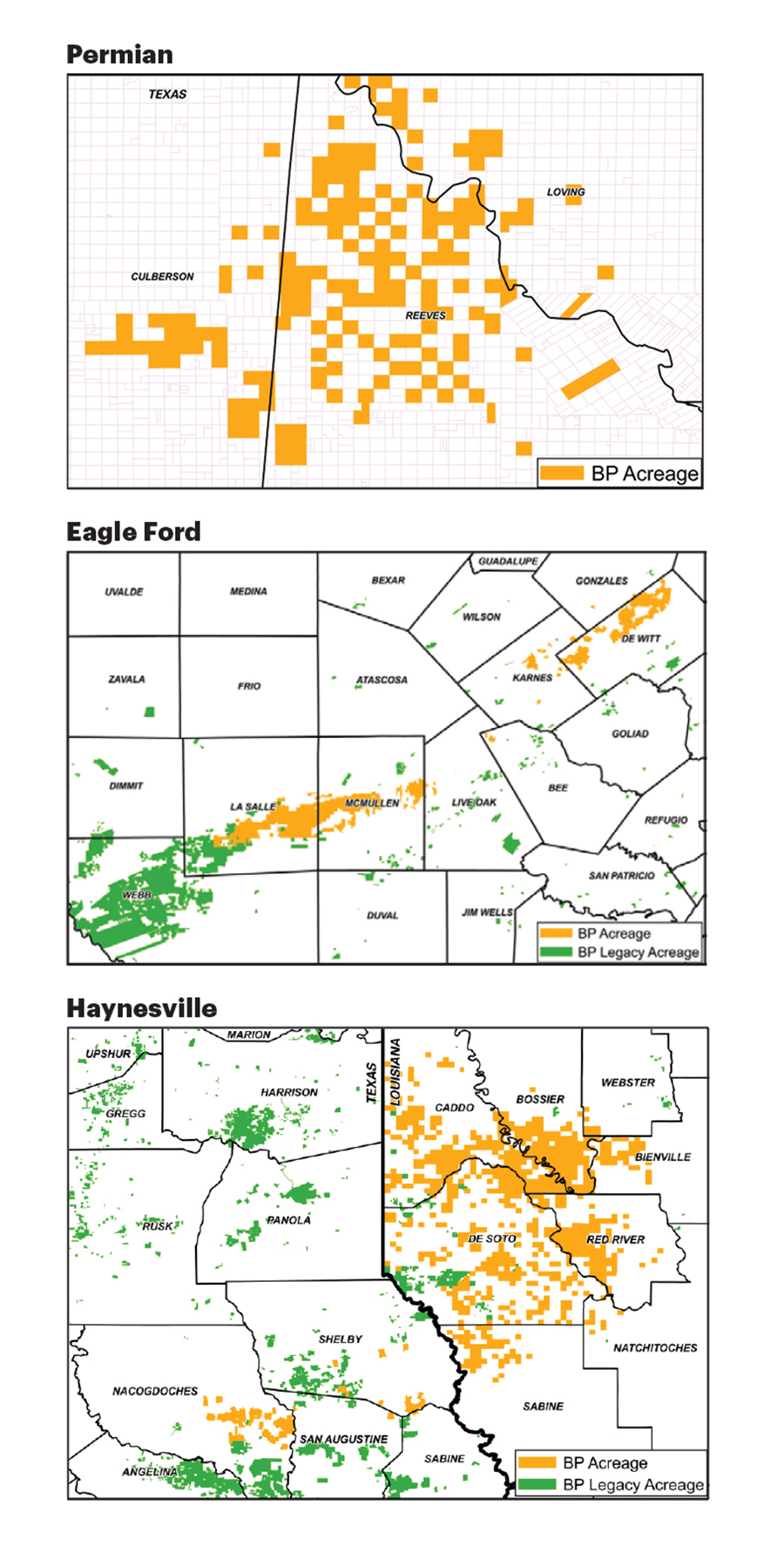

The Permian is BPX’s smallest footprint, with slightly more than 75,000 net acres, but it’s in the core of the Texas Delaware Basin in Culberson, Loving and Reeves counties.

Much of BPX’s emphasis since the BHP deal has been on building out the infrastructure for electrification and efficiency—essentially, an electrical substation network and three centralized processing facilities with interconnected pipelines networks: the Grand Slam, Bingo and Check Mate facilities, the latter of which came online during the spring.

A gas compression station, Crossroads, which is scheduled to come online in 2025, is the final piece of the infrastructure puzzle.

As Koontz explained, the original plan was to build five central delivery points (CDPs), but BPX pivoted to save costs.

“As we blocked up acreage and fine-tuned the designs and the development schedule, we were able to whittle that down to three CDPs and one compression station,” Koontz said. “The compression station will help us for increasing gas-to-oil ratio over time. The reservoir is just built where more gas will come out of solution as the pressure drops. That compression will give us the ability to service all of that gas to keep the oil utilization high. That’s why it’s the last project.”

The company has electrified about 95% of its operated wells in the Permian, up from just 4% in 2018.

“We wanted to power the field, but we couldn’t rely on a third party to build all that up for us,” he said. “So, what we did is we made a deal with our utility partner to buy directly off the transmission line and then build out the system to step it down where we needed it and when we need it. And one of the unique advantages by doing that is we could customize the load design, and so we’re able to run Halliburton’s electric frac fleet off our grid, which is a big electrical load, and most local grids aren’t designed for that. But we designed for that from the beginning to be able to do that.”

“Almost all of our sites now are fracked off the grid with e-frac, and all of our drilling rigs are outfitted with transformers, with Nabors Drilling so that we can drill off the grid as well,” Koontz continued. “We use the electricity to our advantage.”

Edwards said BPX is preparing to experiment with deeper Permian benches, such as Wolfcamp B and deeper Wolfcamp benches. But, for now, the emphasis is mostly on Wolfcamp A and the Bone Spring.

“We still have a significant amount that we would like to better understand technically about the Bone Spring,” Edwards said. “We are working that as we speak, and, obviously, you want to take a measured approach. One of our key philosophies is that we make very small bets, we evaluate the results, and then we figure out how we’re going to apply that to the broader program. You won’t see us go all in on any one bench and dramatically change the program where it could lead to an outcome that’s not something we fully understand. We expect to move into the Bone Springs over the latter part of this decade and then, obviously, into the deeper Wolfcamp benches in parallel or shortly thereafter. We have tremendous runway in the Permian for sure.”

In terms of field development, BPX designs its plans at least five years in advance for wells and then enters a more defined process 12 months-18 months ahead of spud, he said.

“My view is that, typically, somewhere between three and six wells is sort of optimized as it relates to the number of wells on any given pad,” Edwards said. “There’s the time from the initial investment to build that pad to when you start seeing volumes off of it is really important. And then derisking your program by allowing yourself to produce six wells as opposed to waiting for all 20 to be ready to come online all at the same time. I just generally prefer to have a little bit of a smaller subset that gives you a little bit of increased flexibility.”

Koontz said BPX is drilling Permian laterals up to 13,000 ft long and that they’ve largely avoided well-spacing problems that have plagued much of the industry in recent years. BPX benefited somewhat from being later to the Permian game and had the benefit of learning from peers, he said.

And BPX isn’t drilling any horseshoe laterals or unusual shapes, at least not yet.

“We’re not doing anything exotic like some of the stuff you see published,” Koontz said. “But, I will say this, when you build an innovative culture, you’ve got to be willing to hear what they have to offer. They’ve been throwing out some new ideas that I’m not a big fan of, but we’ve got to let them work and be creative and be true to the culture. So, we’ll see. If it works, we’re willing to look at it.

Eagle Ford evolution

With more than 450,000 net acres in the Eagle Ford, BPX is focusing on the oilier portions for now in DeWitt and Karnes counties and also ramping up a new refrac program with partner Devon Energy, focusing mostly on wells that are at least 10 years old.

“The Eagle Ford continues to surprise us in the way of its productivity and what these wells are capable of producing,” Edwards said. “We are bringing on refracs that are, quite frankly, better than the parent wells were, which is just kind of hard to believe. We just couldn’t be happier with what we’re seeing in the way of productivity there. There’s a lot of technical horsepower that we can invest there between the Devon and the BPX side, and the well results are showing it.”

The biggest challenge, he said, is going back in and downspacing between the parent wells.

“I think we are well on our way to solving it. But what is interesting is that the Eagle Ford would’ve been considered probably the simplest and most straightforward basin to execute in from a drilling perspective two or three years ago,” he said. “And, as we move further into redevelopment, it becomes more and more complex.”

BPX first experimented with Eagle Ford refracs in 2019, and the results were underwhelming, but educational, Edwards said. The new program for 25 wells this year is paying off.

“The fracs on those original parent wells where something like 500-pound or 600-pound per foot in the way of sand. The current fracs in the Eagle Ford are generally all 2,000-plus and probably approaching 3,000 pounds per foot of sand in some cases,” he said. “So, ostensibly, frac sizes have grown four times over the last 10 [years] or 15 years, and that’s a remarkable thing. In these shale plays, you look at a well drilled pre-2010 and it’s already a legacy well. Because of the steepness of the learning curve and the technology application, an old well is now 10 years old, and that’s really quite remarkable.”

And new wells are looking strong too, Koontz said. While BPX is more cautious with spacing in the Permian, the company continues to downspace in the Eagle Ford. A new well in the Blackhawk area came online recently at 3,500 bbl/d, which Koontz said may be a BPX record.

Koontz said BPX just added another Halliburton e-frac crew in June to the Eagle Ford that is running off of CNG. He cited 15% efficiency gains in the switch from diesel to CNG.

And the in-basin gas production will ramp up with pricing.

“The Hawkville, in the southwestern Eagle Fordc, has got a ton of running room,” Koontz said of the gassier acreage. “We continue to see that asset outperform, just very high gas rates, but also wellhead condensate. It’s got a really strong profile of rich liquids there, and we continue to see the wells deliver above expectations. So, what we would call core, Tier 1 acreage is a growing footprint.”

Haynesville hopes

BPX’s 500,000 net acres on the Louisiana and Texas sides of the Haynesville depend on gas prices, but BPX is bullish on global LNG demand and rising domestic power demand in the years ahead along with much of the rest of the industry.

“We slowed our activity down to obligation drilling, but it’s a premium gas asset,” Koontz said, noting the acreage quality is strongest in Louisiana. “We’ve got some of the best acreage in the play.”

Despite the HP/HT shale, BPX is drilling its longest laterals in the Haynesville.

“I think we’ve got a pretty good bead on the Haynesville. We’re just looking to see how long of lateral length we can do in a well to find that sweet spot versus technical risk and operational efficiency,” he said. “We’ve gone out to just under 15,000 feet on a handful of wells, and there’s increasing success there. I think we’re gaining confidence in being able to do that. So, we could see three-mile laterals being more of a thing going forward.”

Edwards also is quite bullish on technical gains in Louisiana.

“We are seeing opportunities to drill 20,000-ft laterals. Those kinds of things are constantly under evaluation. Do you get to a tipping point? Yes. Do I think we’re there yet? No. I think that there’s significant efficiency gains that we can have that we’re not necessarily seeing today,” Edwards said.

“From a completions perspective there, what’s been amazing to me over the last couple of years is just generally speaking how efficient these frac crews have become, and just how many rigs it takes to sort of keep them fed and full and continuously operating through the year,” he added. “In the Haynesville specifically, the way we drill, complete, produce these wells is quite remarkable. The 50-plus MMcf/d IP maxes are almost commonplace at this point, and that is just a dramatic improvement over thinking about where we were three to five years ago.”

Because of pricing, BPX is letting some Haynesville DUCs build up temporarily. But Edwards said this is not part of some big DUC program, at least not compared what what Chesapeake Energy and some of the bigger Haynesville players are doing.

He explained: “The difference is, there are DUCs that are being completed now and not brought online. That’s not really a DUC because DUC in and of itself is a drilled but uncompleted well. These are drilled and completed wells that are essentially ready to flow, but not flowing. We are not necessarily in that camp. We are running a rig right now. We are completing wells in 2024. We will exit the year with some DUCs, but we are not building a massive DUC inventory. And we are not building an inventory of wells that are drilled and completed, and we just need to open the valve when prices allow for it. I do think that is a difference now compared to what you’ve seen over the last few years where historically the wells were drilled and then remained uncompleted.

“It’ll be interesting to see how those wellbores respond with significant amounts of frac water sitting in the formation for what appears to be months at a time before they come online,” Edwards said. “It would be an approach that I would definitively study and make sure we fully understood technically before we took it. I just think that’s a bit of a wild card that’ll just be interesting to watch in the industry over the next six [months] to 12 months. How does that physical hedge on gas prices play out?”

Recommended Reading

Crescent Energy Closes $905MM Acquisition in Central Eagle Ford

2025-01-31 - Crescent Energy’s cash-and-stock acquisition of Carnelian Energy Capital Management-backed Ridgemar Energy includes potential contingency payments of up to $170 million through 2027.

Petro-Victory Buys Oil Fields in Brazil’s Potiguar Basin

2025-02-10 - Petro-Victory Energy is growing its footprint in Brazil’s onshore Potiguar Basin with 13 new blocks, the company said Feb. 10.

Report: Diamondback in Talks to Buy Double Eagle IV for ~$5B

2025-02-14 - Diamondback Energy is reportedly in talks to potentially buy fellow Permian producer Double Eagle IV. A deal could be valued at over $5 billion.

Apollo Funds Acquires NatGas Treatment Provider Bold Production Services

2025-02-12 - Funds managed by Apollo Global Management Inc. have acquired a majority interest in Bold Production Services LLC, a provider of natural gas treatment solutions.

Report: Will Civitas Sell D-J Basin, Buy Permian’s Double Eagle?

2025-01-15 - Civitas Resources could potentially sell its legacy Colorado position and buy more assets in the Permian Basin— possibly Double Eagle’s much-coveted position, according to analysts and media reports.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.