Hydrogen is known in the energy world as the Swiss Army knife of decarbonization.

Stepping in where greenhouse-gas emissions reduction is essential, the carbon-free energy carrier’s versatility has industry players factoring in its potential as a fossil fuel alternative in hard-to-abate sectors, heavy-duty transportation, energy storage and industrial processes.

Hydrogen, however, faces some headwinds: higher production costs compared to less expensive fossil fuels, policy uncertainty and a large investment gap, as well as other challenges. Some organizations, including the International Energy Agency, have even lowered growth projections for some forms of hydrogen.

However, the downgrade and doubts by some have not stopped some hydrogen producers and others in the value chain from turning the hydrogen hype into reality. Chevron is among the energy companies pushing forward with hydrogen projects.

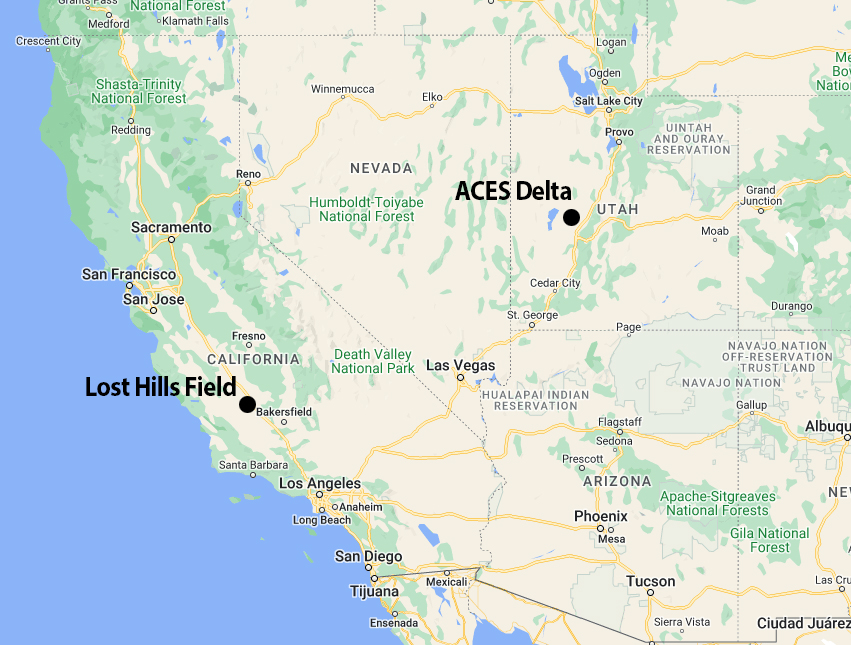

Chevron has said it aims to produce 2.2 tonnes of hydrogen per day—enough to fuel a vehicle for 132,000 miles—using solar energy from its Lost Hills Field in California. Production at Lost Hills could begin in early 2026, adding hydrogen to an area long known for its oil production and powered in recent years by a 220-acre solar field.

The soon-to-be Houston-based company is also the majority stakeholder in the Advanced Clean Energy Storage (ACES) hydrogen storage project in Delta, Utah, and is among the companies working to establish the HyVelocity Gulf Coast Hydrogen Hub.

The challenges and opportunities of hydrogen are something Austin Knight is all too familiar with as vice president of hydrogen for Chevron New Energies and chair of the National Petroleum Council’s hydrogen study, a roadmap to scaling low-carbon intensity hydrogen production in the U.S.

Knight spoke to Oil and Gas Investor about the company’s projects and what the hydrogen sector needs to overcome obstacles.

Velda Addison: Chevron has a ton of hydrogen initiatives underway: ACES Delta, a solar to hydrogen project in California, the HyVelocity Hydrogen Hub. Why is Chevron so bullish on hydrogen?

Austin Knight: Hydrogen is happening … and it’s one of our core beliefs that, in the future, as we move to lower-carbon energy solutions, hydrogen is not only something that’s necessary, it’s something that fits really well with what we know how to do. We’ve looked, of course, at all the things that could be necessary to help get to the climate goals that are in place. That helps inform us about how we think the energy system’s going to evolve. But not every one of those is right for us. Hydrogen is one of those areas where, for certain sectors, it is the best solution to reduce the CO2 emissions of the current sectors. It’s really around heavy industry, large-scale refining, petrochemical plants, steel production—things that require a lot of heat. Hydrogen is a great way to do that without the resulting CO2 emissions.

Heavy-duty transportation is another one because today we see a drive toward the desire to have more and more zero-emission vehicles. But for large trucks that go long distances, carry big loads and have high utilization, that’s a difficult solution for batteries to fill, but hydrogen can fill that gap. Again, zero emissions from hydrogen.

And, you mentioned ACES. ACES is a great solution for the energy system. As we expand renewables, you still want to be able to keep the lights on. And so, the way I think about it in ACES is there’s a giant battery that hydrogen can act as to ensure that, although you can’t control wind, you can’t control sun, you can use the excess in the system, store that energy as hydrogen, and then allow that to be sent back to the grid as power production when it’s needed. There’s also a lot of places in the world that don’t have wind and sun, so they need these types of solutions as well. That’s where I think hydrogen fits.

VA: It seems hydrogen storage is not talked about as much as it probably should.

AK: Hydrogen storage is really important, especially in that grid reliability case. A lot of what you may see when we talk about how hydrogen might move around the world and where it goes, moving hydrogen, say, between continents, is oftentimes a difficult feat. Ammonia is something that people talk about. So, then it’s ammonia storage rather than hydrogen storage. ACES’ massive hydrogen caverns can store the equivalent of 300 gigawatt hours of electricity [and] put [it] onto the grid, and 300 gigawatt hours is multiples over what is currently installed in terms of batteries connected to the grid today.… But not only that, it’s long-term storage. A lot of the batteries being connected today are intraday batteries. They will charge a bit during the day. They’ll discharge some in between the sun and the wind profiles, but they’re not seasonal. So, I think you really will see a system where you need both, right? This is an all-in type of system. Hydrogen will play one of those roles.

VA: You speak a lot about the positives, and the momentum is building. But hydrogen is not without its challenges when it comes to cost, infrastructure and building up demand. What do you believe is key to overcoming some of these challenges?

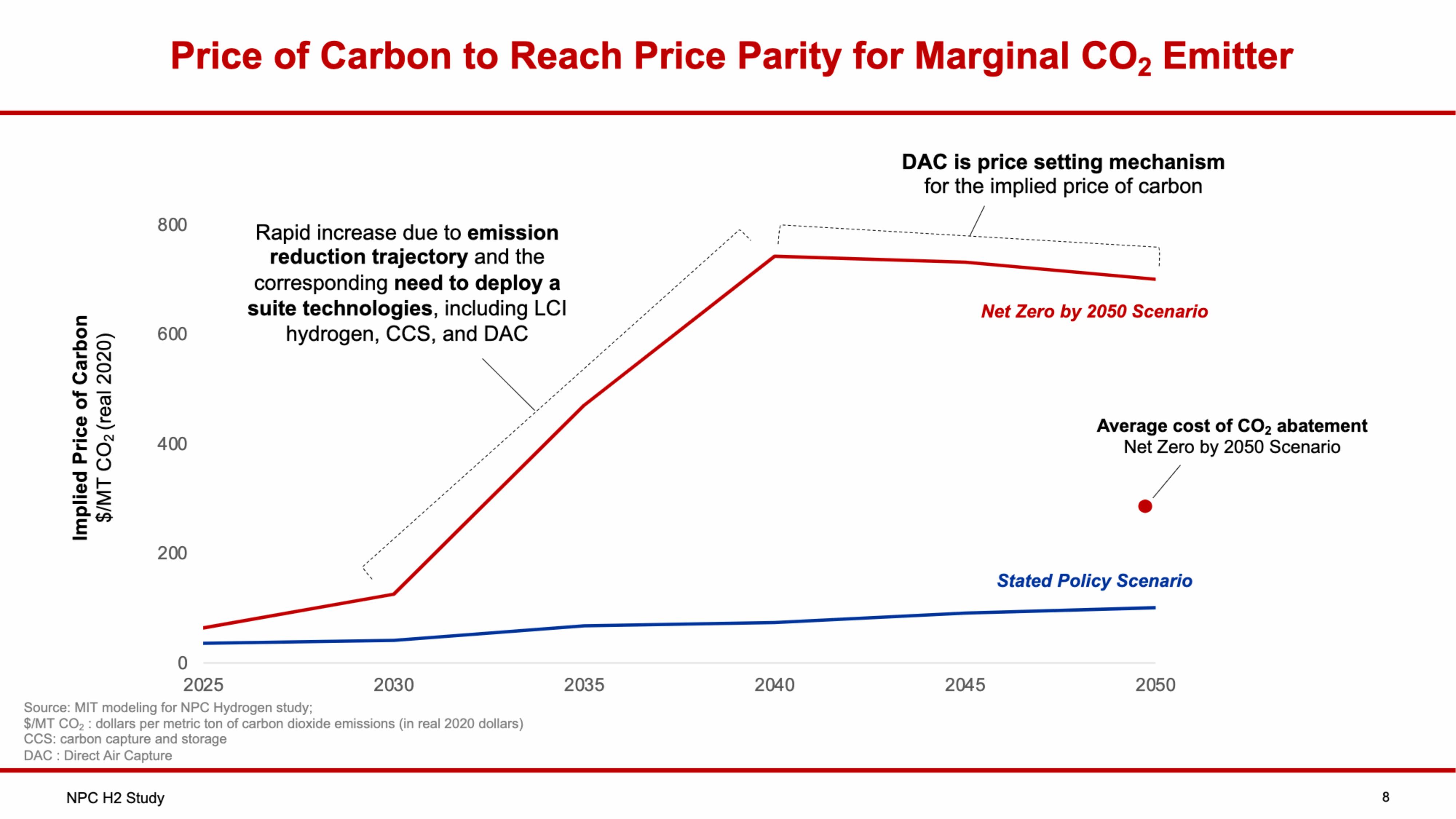

AK: How do we get from where we are now to where we think hydrogen needs to go in the future is the question that the secretary of energy asked us. Secretary [Jennifer] Granholm wanted to know not only what is the role of hydrogen, where does it fit, but what are the gaps in actually making this a reality? And so, Chevron led a study that I led across all industry. We had 100 different organizations involved, 200 different people or more, not just industry. NGOs participated, academics participated. We did a ton of modeling with MIT to not only look at where does hydrogen actually fit in the system in a way that makes sense towards the climate goals, but what’s the reality of the gaps.… Now and over the long term, even by the time you get to 2050, the cost gap still exists between the lower-carbon intensity solutions and the higher-carbon alternatives.

We have quite a few recommendations, but the key thing is around valuing those carbon emissions. Do you have a price on carbon; some way to value this reduction? We think it’s a great solution. It’s something then that the markets can work, solve technological challenges, scale up the solutions, build out the infrastructure, but all of that’s required to then get these costs down. And we have to remember, we’re at the early activation stage right now and we basically laid this out in activation, into expansion and then at scale deployment of what does this look like and what are those critical factors? So much is about policy and at the same time, as you start to activate the system, you start to build out infrastructure and bring down the cost of some of the technology solutions.

VA: Of the 23 recommendations, which ones do you think should be tackled sooner rather than later?

AK: The biggest one, when you look at the policy piece, we really had two primary recommendations that I would highlight. One is a price on carbon. We recognize, the study recognizes, and I think Chevron would agree, a price on carbon is going to be the most efficient way to achieve these goals.… We also proposed a couple alternatives, recognizing that maybe politically that’s going to be difficult to get across the line. There are a couple other things you could do, but it’s only a surrogate for carbon pricing.

The other piece was permitting. Even with great policy, economic incentives, clarity on policy and everything that you would want, you have to be able to permit these projects. And it means carbon storage, it means large-scale production hubs and it means the electricity buildout. So, it’s renewables; it’s all the infrastructure associated with that. It’s these pipelines to move this product around. Again, we’re not trying to put hydrogen everywhere. We want to target that where it makes the most sense to achieve our goals as the best alternative. It still requires all of that to be built out, which requires the ability to permit.

VA: There’s a clear cost gap between blue hydrogen and green hydrogen. Blue hydrogen has … a lower emissions profile compared to other fossil fuels but a higher emissions profile compared to renewables. Looking at emissions, what steps are being taken or can be taken to make natural gas cleaner when it comes to hydrogen production?

AK: Today, we have solutions that can be implemented and can start at scale with a very low carbon intensity. And that’s based on making sure you’re responsibly sourcing your gas upstream, reducing methane emissions, which we’re already doing and committed to.… That’s one element of it. And another one is renewable natural gas/biogas. These are recognized in California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard as negative emissions. We can ramp that up. And I think these things all are actually true emissions reductions that can be tracked and can be credible in the system. The policy needs to recognize it. I want the policy to recognize all of these solutions without only picking winners and saying, it can only be this or can’t be that, because we need viable valid solutions.

Now, that blue path can be done at a much larger scale today than green. And so, we’re in green with the ACES project. And we also think large-scale blue is a great solution because as you build that out and you build out the infrastructure associated with that, you can also continue to transition to lower and lower carbon with the benefit of having, already, the infrastructure that you can add onto with the green pathway. The green pathway today is still very, very young and it’s scalable, but it’s still very small.

And so, you not only have a cost difference between the two, you have a carbon intensity difference and you have a very significant feasibility difference on the scale of what can be done. This is an area where these two things should go hand in hand, and we’re going to be in both. There are different reasons or justifications behind the pace of which either one would be adopted because the world is not uniform and resources aren’t the same everywhere and policy’s not the same everywhere.

VA: Let’s talk about more about Chevron’s projects. ACES Delta, that’s the big one. What’s happening there now and what are the upcoming milestones that you’re looking to hit this year and next year?

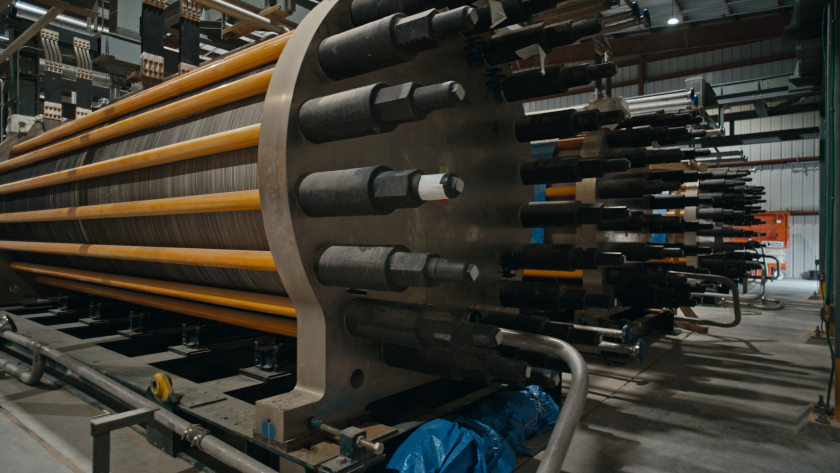

AK: I love this project.… You can touch it. You can see it. You can put your hands on something real, and there aren’t many projects at that scale and at that stage in the world today. We are wrapping up construction, moving into commissioning. We expect that next year we’ll be operating. There are 40 electrolyzers in place already today, and we’ll have to hit the point of the project very soon where you start to energize these and move toward hydrogen production. We have two massive salt caverns being solution mined, and both of these sit about a mile below the surface of the earth. They’re about the size of the Empire State Building. We’re talking 1,500 feet tall. All of the infrastructure is there. The final bits of the solution mining are going on right now. It’s real progress that you can see.

Across the street, there’s the development with the Intermountain Power Project; they call it IPP Renewed. You can see there, in real time, the replacement of coal. There’s a coal plant that served that area for quite some time, for more than 30 years. And next door being built out are the new gas turbines. What’s just fantastic about all of this is as the world goes to more and more renewables, you need something that can ensure you keep the lights on. And this is just the confluence of all those great elements, and it’s a lot of renewable build out. It’s also the geology that’s required, the customer commitments and all the infrastructure to connect it. It’s all there and you can see it. You can put your hands on it. It’s really real.

VA: You think that’s something you all can replicate maybe in Texas?

AK: I hope so. The project itself has a lot of scalable potential, and this is the first phase. It’s something that I think you’re going to need more of as the energy system grows and as the energy system moves to more renewables. Others are very interested in similar concepts. What I think makes any of this work are those elements that you could replicate. It’s the customer commitment to decarbonize, to value that carbon abatement. It’s really strong partnerships across the value chain that make it work. And it’s all of that infrastructure and technology. It’s people taking the chance to do the problem solving and to develop the solutions that actually work. So, we’ll see what’s next.

VA: What’s the latest with HyVelocity?

AK: HyVelocity still represents one of the best opportunities there is to benefit from everything the Gulf Coast has to offer. You’ve got the gas supply, again, this responsibly sourced gas. You’ve got the infrastructure. You’ve got pipelines and energy systems and export facilities and all these things. So, there’s a number of partners at HyVelocity that are very committed to that type of vision. We are still finalizing the negotiations with DOE to enter in to what DOE is calling Phase One of these seven hubs. And so, we continue and we still like the concept of HyVelocity.

VA: Is there anything else you want to speak on?

AK: Out in the Central Valley of California, we’ve also been testing some concepts. We have a trial that’s been going on with Solar Turbines, which is a Caterpillar company, in our operations there to make sure that hydrogen can be used at high quantities in gas turbines [and] that you can control for [nitrogen oxides] if the technology will work. That’s been really a great success and something we’re proud of, where we’ve stepped out and started to make commitments to do that on our own, to prove what’s possible.

And at the same type of site, not exactly the same area, but Central Valley, California, as well, we are going to utilize a solar field that we have already that’s underutilized and take that excess and produce hydrogen with that to support some of the early markets in California around transportation. It’s a really great reuse case of oil field production where we have water, infrastructure and underutilized solar. We think there’s possibilities to do more of that and scale it, but it’s going to have to make sense and fit with the market adoption.

Recommended Reading

E&P Highlights: Jan. 27, 2025

2025-01-27 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines including new drilling in the eastern Mediterranean and new contracts in Australia.

CNOOC Makes Oil, Gas Discovery in Beibu Gulf Basin

2025-03-06 - CNOOC Ltd. said test results showed the well produces 13.2 MMcf/d and 800 bbl/d.

E&P Highlights: March 24, 2025

2025-03-24 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, from an oil find in western Hungary to new gas exploration licenses offshore Israel.

E&P Highlights: March 31, 2025

2025-03-31 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, from a big CNOOC discovery in the South China Sea to Shell’s development offshore Brazil.

Oxy CEO: US Oil Production Likely to Peak Within Five Years

2025-03-11 - U.S. oil production will likely peak within the next five years or so, Oxy’s CEO Vicki Hollub said. But secondary and tertiary recovery methods, such as CO2 floods, could sustain U.S. output.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.