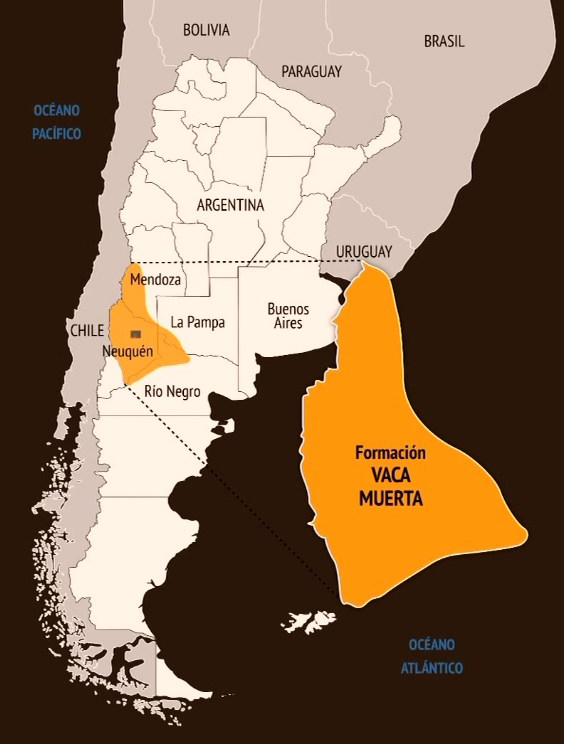

Argentina’s Neuquén Province Energy Minister Alejandro Rodrigo Monteiro is making a case for Argentina’s Vaca Muerta Shale to be considered a super play—the Permian 2.0.

The play has been transformational for Argentina’s hydrocarbon sector and could drastically change energy trade in the Southern Cone region of South America as exports ramp up to Bolivia, Brazil and Chile. Additionally, a 25 million tonnes per annum (mtpa) liquefaction plant to be located on Argentina’s Atlantic coast and proposed by state-owned YPF SA and its Malaysian counterpart Petronas will open further markets for Vaca Muerta gas.

Monteiro spoke with Pietro D. Pitts, Hart Energy’s international managing editor, on November 29 in an exit interview about the Vaca Muerta’s progress so far and its potential.

RELATED

Achieving Energy Self-Sufficiency: Argentina’s Game Changing Vaca Muerta

Pietro Donatello Pitts: Just how important is the Vaca Muerta for Argentina?

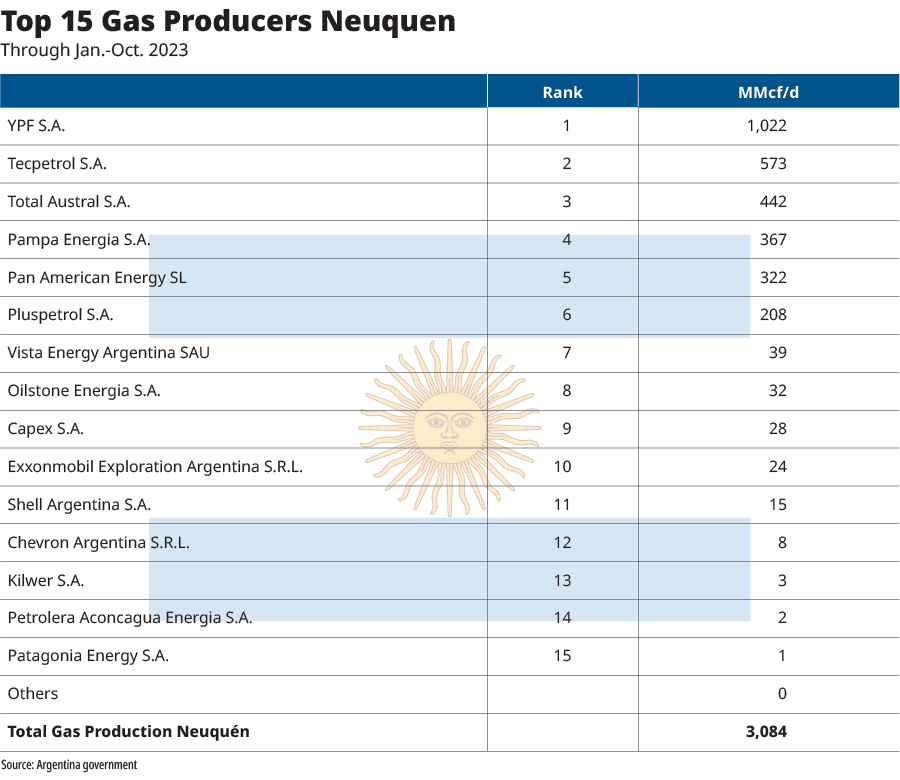

Alejandro Monteiro: If Argentina hadn’t developed the Vaca Muerta, today the country would have about half the oil production it has and one-third of the gas production it has. A little less than 60% of Argentina's gas production is unconventional while around 50% of its oil production is unconventional. In the case of gas, over 90% is consumed internally, and in the case of oil, it’s close to 80%.

Without the development of Vaca Muerta—Argentina with all its macroeconomic problems and the lack of reserves at Argentina’s Central Bank—the country would have imported hydrocarbons and energy worth over $20 billion in 2023. Or, said another way, considering the currency problem, the country would have had a hydrocarbon bill of $20 billion. And by not having currency, the country couldn't have acquired these hydrocarbons and energy. In other words, Argentina would’ve had serious energy supply problems, in addition to problems related to its Central Bank reserves.

Vaca Muerta has allowed Argentina to balance its energy trade. We continue to import some energy, especially LNG during the winter as well as Bolivian piped-gas, but with rising Vaca Muerta oil and gas exports our energy trade is already in balance. We have almost completely eliminated the need to import energy. [This is important] if we consider that in 2011-2012, Argentina was importing about $12 billion in energy, mainly gas.

Argentina should have a positive energy balance of about $4 billion in 2024 as production grows primarily due to infrastructure projects moving forward that enable more exports. Internally, refineries are being supplied and due to the improved gas infrastructure, we’ll only have to import some LNG in the winter.

We plan to completely displace all Bolivian gas [imports]—the [land-locked country] has warned that in 2024 it will not be able to continue sending gas to Argentina—and reverse the gas flows along the northern gas pipeline as Bolivian and northern Argentine basins are running out of gas production. Currently, the pipeline is set up for Argentina to import Bolivian gas, but the plan is for Argentina to be able to export its gas to Bolivia and on to Brazil. Basically, the gas pipelines come from Bolivia and go to the center of Argentina as well as gas pipelines that come from southern Argentina and go to the center of the country.

The national government [of outgoing President Alberto Fernández] put out a pipeline tender, but it wasn’t awarded. So, it’s pending to be awarded by the incoming government [of president-elect Javier Milei]. If awarded soon, companies have [the] potential to finish work before next winter so Neuquén gas can supply a great part of northern Argentina.

Again, Vaca Muerta’s development can be seen through all the energy that Argentina stops importing and also through the energy production export and the dollars this generates for the country.

RELATED

Argentina Officials in Houston Boast Vaca Muerta’s Potential

PDP: There has been some interest from companies in Argentina’s offshore region. Do you think that’s a better strategy or is the Vaca Muerta their best option?

AM: Considering the learning curve that we’ve had with Vaca Muerta in these first 10 years of its development, the risk is very low. We have an enormous resource—308 Tcf or enough gas for around 200 years and around 27 Bbbls, enough oil for over 80 years—that has undergone enormous advances in terms of efficiency and productivity. So today for an investor, the Vaca Muerta offers a low-risk, high-profit return.

There is also the first shale-related exploration in Santa Cruz in Palermo and the spudding of an offshore well by a consortium made up of Equinor, Shell and YPF, which will be the first exploratory well. But Argentina still doesn’t have an alternative hydrocarbon project that can compete [with the Vaca Muerta].

It will take time to get another project to the state of maturity of the Vaca Muerta. And as I look over the short-and-medium term hydrocarbons investment and development horizon in Argentina, it will be related to Vaca Muerta due to its low-risk. In terms of profitability, due to the improvements in efficiency, the results are very good and comparable to the Permian. In some cases, they have even had better results than in the Permian, but not in terms of productivity.

PDP: What does Argentina need to do to really be called the Permian 2.0?

AM: It doesn’t depend on geology. It depends on the decisions in terms of economic policy of the country and whether Argentina can get organized on the macro-economic front. That’s to say, Argentina opens itself to the world so that investors can bring in money, earn money and make profits and then invest again in Argentina or anywhere they want.

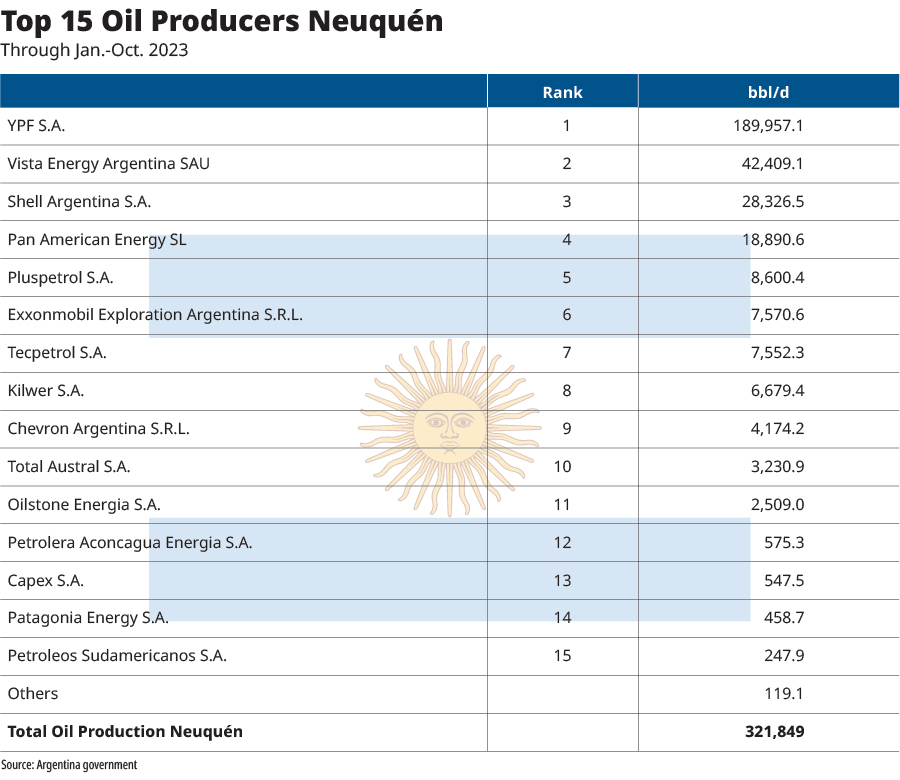

By 2030, we expect production in Neuquén to exceed 1 MMbbl/d. Today we are producing 350,000 bbl/d. Our projections are based on a scenario in which Argentina doesn’t achieve a complete opening of its economy. So this is a moderate scenario. If Argentina with the new government is able to organize itself and generate confidence in investors, then that projection will be surpassed and we’re going to have more growth problems than we have today, which would be good problems. Only around 10% of the Vaca Muerta is under development, so if we advance with more projects, then the 1 MMbbl/d oil production forecast is going to be vastly surpassed. But in order for that to happen, the conditions need to be created so that international capital can invest in Argentina. Because … the capital we have in the country, it isn’t enough. So beyond the capital, we still need service companies, hydraulic fracturing companies, as well as technology and equipment, among other things.

We have to demonstrate that in addition to having a world-class resource, these are the needs that we have, and not only in terms of materials, equipment and technology since it’s a permanent race against efficiency. You always have to manage to continue improving in terms of efficiency because the world is advancing in that sense. We can’t just think oil will be $80/bbl and that LNG will be around $12/MMbtu. We have to have a project that is resilient, that supports low price scenarios and that can continue to be produced and that can continue to make money.

PDP: Have you changed your mind since our last discussion regarding the Argentina LNG project proposed by YPF and Petronas and when it could realistically export its first LNG cargo?

AM: Work on a new law was sent to the Congress of the national government, which establishes certain regulations regarding fiscal security and security of supply related to a potential LNG project. With the change of government, there’s uncertainty about what will happen to this law.

Under the current YPF leadership and with the agreement they have with Petronas, the conditions established in that law are appropriate to start the liquefaction project. If this law is approved, it’s because the national authorities about to enter the government agree with those terms, which could see YPF and Petronas move forward with initial construction works. But, considering that equipment needed for the facility’s construction isn’t made in Argentina, I don't see a greenfield project before 2030.

However, the Argentina LNG project has an intermediate stage, and under the agreement Petronas could bring in one of its liquefaction ships until they can construct the first modules of the facility. If this option is viable and feasible, we could perhaps have LNG as early as 2026 or 2027. But it also depends on how the law advances as well as new changes at YPF already announced by the incoming national government.

PDP: So, there is now a lot of uncertainty related to the incoming government and then YPF?

AM: Regarding LNG? Yes, because we have to see what the new government’s vision will be regarding the intervention of the state in the economy. If the government gains the trust of investors, the law wouldn’t be necessary. But, based on Argentina’s track record, it will be difficult for investors to have trust without the law. So, it’s important to have the law combined with a new vision from the national government that instills confidence in the private sector and towards investors, both private and foreign. Only then can this project advance.

PDP: The Nestor Kirchner pipeline aims to boost shipments of Vaca Muerta gas but bottlenecks still need to be resolved, right?

AM: The Kirchner pipeline has two stages. The first stage also has two stages. The gas pipeline was built and started operations in August 2023. In its intermediate stage, it has a transport capacity of 11 MMcm/d. [The] second stage of the first stage includes the construction of compressor plants at both ends of the gas pipeline. The compressors are under construction, and when installed will allow the pipeline to boost its transport capacity to 22 MMcm/d.

Again, even with the conclusion of the first stage of the pipeline, there will still be a need to continue importing LNG during the winter months.

What’s next is the bidding, awarding and construction of the second stage. The current national government started the bidding process with some financing from multilaterals from China. Today, everything is on standby as the incoming government doesn’t want to continue doing public works with the public budget, but instead wants public works to be done with agreements from the private sector, via concessions with the private sector or the participation of public-private or contracts related to construction, operation and maintenance and fees. Until the new government takes office and ultimately makes the decision regarding large infrastructure projects, things will be on standby.

PDP: How are Argentine gas exports to Chile since you restarted the gas flows?

AM: Today Chile is our main gas export destination. In 2023, we practically exported gas to Chile the entire year, including the entire months of July and August, because we had surplus production with respect to the capacity of the gas pipelines that we have for internal supply. We had enough gas to continue supplying the internal market as well as Chile.

With work to revert the direction of the northern Argentine gas pipeline, we will have two pipelines that take Neuquén gas to northern Argentina that can be sold to northern Chile.

Chile is a very important market for Vaca Muerta gas. We have to continue adapting the infrastructure to reach the different gas export points. For Chile, it’s beneficial to buy gas from Argentina because in comparative terms with LNG, it’s cheaper and easier to ship to certain places in Chile. Remember, Chile imports LNG and uses trucks to ship some volumes to others close by and distant internal locations. So, the cost of gas supply that comes from LNG, in relation to Argentine gas we can export via gas pipeline to different parts of Chile, is much costlier. We have been working well with the Chilean authorities, regaining confidence in [an attempt to get them] to again view Argentina and Vaca Muerta as a reliable gas supply source.

PDP: Considering the gas trade history between Chile and Argentina, is the idea of Argentina exporting piped gas to Chile to be liquefied and exported as LNG to Asian markets being discussed?

AM: From the perception of the private sector there have been conversations. Gas-producing companies in Argentina have raised the possibility of taking advantage of the Quinteros regasification facility in Chile, which could be converted into a liquefaction plant, to export Argentina gas as LNG via Chile on the Pacific side of South America to target the Asian market.

It’s a concrete possibility for the incoming national government, which has a more open vision with regard to international trade and Argentina’s economy and its impacts globally. Obviously, it will require many agreements between Argentina, Chile, the offtakers and investments that need to be made.

The investment would be made in Chile, so there it would probably also have a much lower cost than what it could cost to build a new plant in Argentina. But the supply is still from Argentina, so there is the Argentine risk, which relates to breach of contract, which has happened [in the not-so-distant] past. If we can rebuild this trust, the Argentine risk would decrease and the entire project would be competitive.

RELATED

Argentina Plans Ramp Up of Production, Export Oil to Chile

Having said that, to supply a Chilean LNG export plant, there would need to be a dedicated gas pipeline from Neuquén to Chile that would be much longer than the Neuquén-Bahia Blanca pipeline that will eventually feed Argentina’s proposed LNG plant. Importantly, any new pipeline from Neuquén to Chile would have to cross the southern Andes mountain range, which is no easy feat.

Also in Chile, where the Quinteros facility is located, there are potential environmental risks related to earthquakes which don’t exist on the Atlantic side. This would also create extra costs for any large-scale LNG plant in Chile. So, the idea of sending Argentine gas to Chile for export as LNG doesn’t offer many advantages other than Chile’s closeness to Asian markets.

But Argentina also has the opportunity to move forward a potential petrochemical project due to the characteristics of the Neuquén gas. Again, it’s feasible to have liquefaction capacity on the Atlantic side [of southern South America] with an eye on European markets which will continue to demand LNG. Vaca Muerta gas and LNG can make it into markets that will have high demands related to carbon emissions and greenhouse gases, which is the case of Europe. While it’s a challenge, it’s also a plus so Argentine gas can enter European markets.

Argentina has plenty of gas when Europe lacks gas in the winter, so we also have that advantage.

Recommended Reading

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.