Harold Hamm remembers a point in the 2000s when the pipelines out of the Permian Basin were practically dry.

The shale revolution was getting underway, and the new volumes from West Texas could not yet match the infrastructure already in place.

“We had pipes in place that could handle the volume. Basically, at that time, they were mostly empty,” said Hamm, who owns the private E&P Continental Resources.

—Harold Hamm, founder and executive chairman, Continental Resources

The situation would change. Before the end of the 2010s, crude pipelines were so full that alternative means of transport had to be found.

Now, Hamm and his team see the same problem arising with natural gas. Producers in the area have long known that, as shale plays age, they produce more gas and less crude.

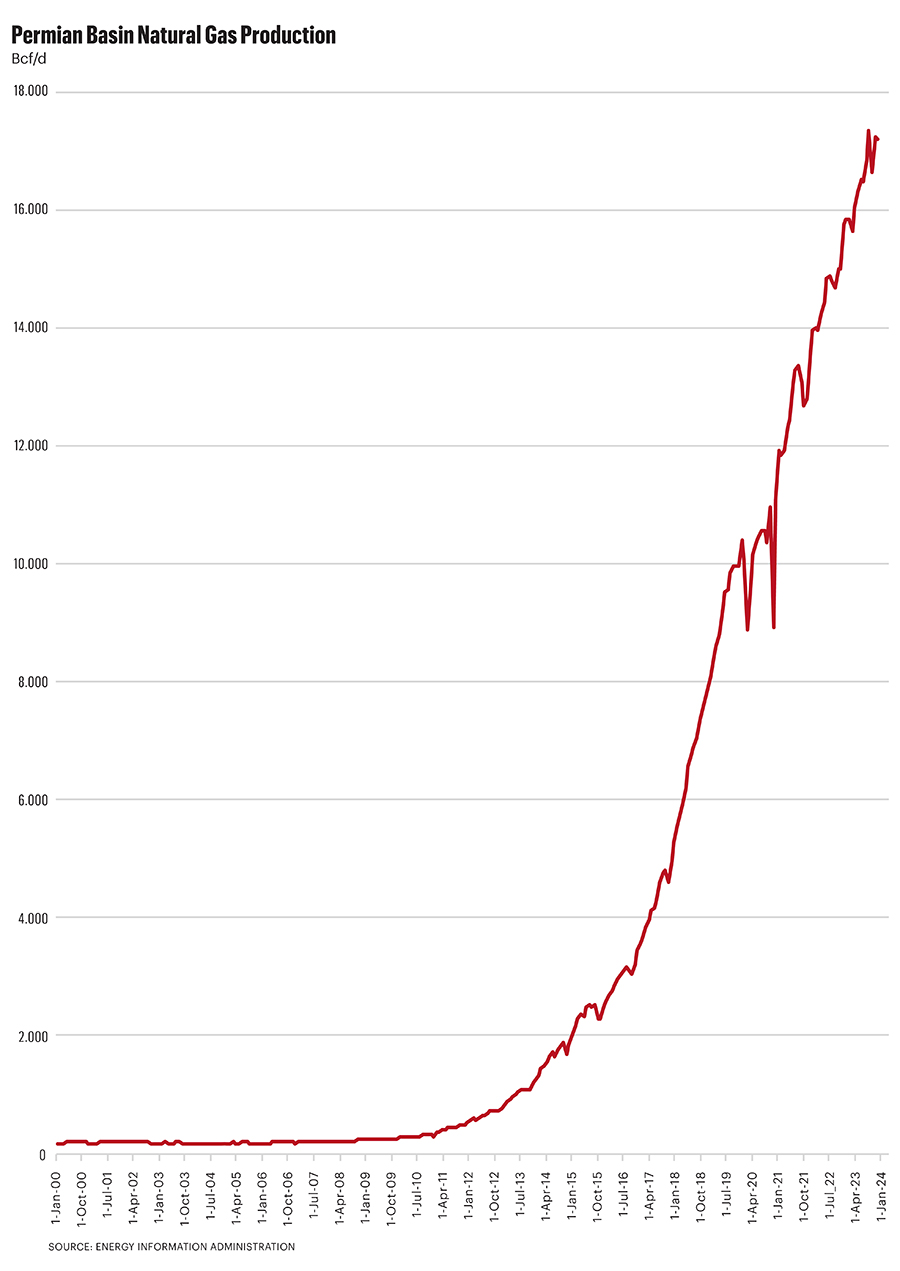

The gas-to-oil ratio at primary sites in the Permian tripled between 2018 and 2023, according to an analysis by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). However, as price of crude has remained strong—above $70/bbl for more than two years—producers have continued to increase crude production.

The resulting gas oversupply in the Permian has dropped the region’s natural gas price into negative territory and forced some companies to seek permission to flare excess methane.

A new major gas pipeline is expected to open this year and will bring some relief.

However, analysts have forecast gas takeaway capacity will fill in only a couple of years. Another major natural gas pipeline project would therefore be needed in the 2026-2027 timeframe. Several projects are in development, but none have reached the final investment decision (FID) stage of the process. Construction for a major greenfield pipeline usually takes at least two years.

Meanwhile, the federal government is implementing new rules restricting flaring and monitoring gas emissions. Producers may face a problem, Hamm said. If crude production produces more gas than can be moved, crude production may be trapped.

Midstream companies have built a crude network expected to handle the increasing flows into the next decade. The picture for natural gas is less clear. Industry watchers say new pipeline capacity will be needed sooner rather than later.

“What we’re trying to prevent, as the rules change and time goes on, is the ordeal of building out volume before building out the pipes,” Hamm said. “That has to change and should have already changed.”

New plumbing

Midstream companies, meanwhile, are dealing with a changing region and industry.

Since the 1920s, people have been exploring the Permian Basin for oil, each generation trying out new tools and technologies—and always having to re-do the plumbing.

“The Midland Basin’s been drilled for 100 years,” said Stephen Luskey, executive vice president and chief commercial officer of Brazos Midstream, one of the larger independent midstream companies operating in the Permian. “There’s been infrastructure on both sides of the basin for that long.”

The gathering and processing part of the job means that companies have to handle new, complicated setups at the production site.

“When we first started, you were talking about one or two horizontal wells per pad. Today, we’ve got folks drilling eight to 12 per pad,” Luskey said. The infrastructure required has scaled up accordingly. Large pipes, more compression, more gas plants are all needed to handle the new output.

“Fortunately for us, unfortunately for the operators, (the new network) hasn’t existed,” he said. “What you’re seeing, in essence, is folks like Brazos are having to re-plumb the basin, basically.”

Room for crude

The plumbing for the Permian has often been difficult to time.

Permian crude production outpaced the midstream network’s ability to take it away near the end of 2018. As production surged, crude pipelines were at capacity, and producers sometimes had to rely on more expensive rails and trucks to haul crude away, according to an analysis at the time by S&P Global.

Pipeline builders quickly caught up. By the time the Permian hit 2020 pre-COVID peak crude production at a little under 5 MMbbl/d, takeaway capacity had already surpassed 6 MMbbl/d as the Exxon Mobil-operated Wink-to-Webster line came online, with a capacity of 1.5 MMbbl/d.

By 2023, total egress capacity for the Permian was about 8 MMbbl/d, well ahead of production levels. There was enough excess capacity that Enterprise Products Partners decided to convert its Seminole Pipeline into an NGL transport conduit in October 2023, subtracting 210,000 bbl/d from crude capacity.

In May 2024, the U.S. Energy Information Administration reported that Permian crude production had hit 6.16 MMbbl/d. While overall egress capacity is not a problem, there are some issues that major midstream companies are trying to address.

One is in Corpus Christi, Texas. The port, with recently enlarged shipping channels and growing export facilities, is the most attractive destination for crude in the state, according to an analysis by RBN published in early May. As a result, the four pipelines serving crude to the South Texas City averaged over 90% capacity in 2023.

Two pipeline expansion projects serving Corpus Christi are in the works. On May 9, Enbridge called a binding open season for its Gray Oak Pipeline, with a proposed capacity expansion of 120,000 bbl/d and project completion in 2026. Enbridge may adjust the proposed added capacity, depending on the demand from the open season. According to RBN, private EPIC Midstream is considering a similar expansion on its EPIC Crude system, though the company has not determined a definite time to move forward.

Either way, the overall Permian crude capacity situation should be able to handle the region’s production growth, as noted at the 2024 Enverus Evolve conference in Houston. The region’s production output is expected to grow about 2 MMbbl/d by the end of the decade, after growing 5 MMbbl/d over the last decade.

“What we have now is a very healthy midstream system. They’re doing very good in the oil patch,” Hamm said. “Whether it’s the Kinder Morgans, the Energy Transfers, Enterprise, whoever it is, they’re moving a hell of a lot of volume.”

Gas light

With that volume comes a whole lot of natural gas, which is what Brazos planned for, said company CFO William Butler.

When Brazos Midstream formed, its founders knew they wanted to focus on the development of gas pipelines and facilities. At the time, natural gas was in a bear market, thanks to the development of gas-rich shale basins in Appalachia, Texas and Louisiana.

That left the group with a choice, Butler said.

“We needed to either go into the most economic, lowest-cost gas basin, or we needed to go into a basin where they produce a lot of gas, and they don’t care what the price is,” he said. “So, we wanted to go to an area where the wellhead economics were driven by oil prices, not by gas prices.”

Since its start, the company has also seen changes in the field and boardroom.

M&A was a hot subject for the Permian E&Ps last year. In early May, Kinetik Holdings announced a $1.3 billion midstream deal to acquire Durango Permian. However, Butler said the same level of merger activity has not been seen overall by midstream companies.

“We kind of think the writing’s on the wall,” he said. “But we’ve got a lot to do out here. We’re building a lot and have a lot of work to do before we think about something like that.”

The company has focused on building up its lines and processing facilities and is currently working on about 200 miles of high-pressure pipe and a processing plant in the Midland Basin.

Butler said that for the typical Permian E&P, methane gas will make up less than 5% of the company’s revenue, making the price irrelevant to the producer. Midstream companies, however, remain focused on the volume going into their lines and plants.

“The volume is going to come by virtue of the oil price in the economics of the Permian Basin. Both the Midland and the Delaware have sub-$40 breakeven oil prices,” he said. “There’s no better place to be.”

The place can still throw up some obstacles. Brazos leaders said they have seen a sea of change in the supply chains in the basin ever since the beginning of the COVID pandemic in 2020, especially in the processing to make NGLs.

The company’s plants have avoided becoming a production bottleneck, Butler said, but the company has to plan well in advance for supplies.

“What used to take us 10 to 12 months in building a processing plant takes probably 18 to 20 months,” he said. “Compression now is a 52-week lead time to purchase. I mean, we used to be able to call and just get it off the shelf.”

Luskey said the company is often bidding for braised aluminum heat exchangers with corporations building LNG terminals. Utility companies are overloaded with requests.

“In typical oil and gas business fashion, everybody tries to ramp up at the same time,” he said.

Once the project is done, however, Luskey said the Brazos will not have difficulty shipping NGLs to customers.

Two NGL pipelines are under construction in the Permian. Targa Resources aims to place the 400,000 bbl/d Daytona line in service by the end of the year.

Enterprise is targeting a first half of 2025 in-service date for the 600,000 bbl/d Bahia project and has temporarily converted its Seminole crude pipeline to transport NGLs in response to high demand in an area where E&Ps are focused on crude.

“The growth is going to continue to happen,” Luskey said.

Coincidentally huge

According to the EIA, the Permian was the country’s second-most productive natural gas basin at 17.2 Bcf/d for March. The gas-focused Marcellus Basin averaged 25.315 Bcf/d.

The price of natural gas has been in the doldrums for most of 2024, dropping below $2/MMBtu at the Henry Hub futures market at the beginning of February and not climbing above the mark for three months. By mid-May, the price had climbed to a still-anemic $2.25/MMBtu.

Low prices and high volume can cause some problems, however.

The overall low demand for natural gas, coupled with spring maintenance work on several area gas pipelines, drove the spot price at the Waha Hub near Pecos, Texas, into negative territory. Producers now had to spend more than $1/MMBtu for a transport company to take the gas off their hands.

According to Reuters, the resulting traffic jam on the West Texas gas network led some companies to resort to flaring. During the last week of April, the Texas Railroad Commission approved 21 flaring requests from operators, primarily in the Permian and the Eagle Ford Shale, more than four times the requests that had been approved during the same time in 2023.

Luskey said that flaring can also show a lot about the infrastructure it’s coming from. As an independent, the company prefers to build reinforced networks that can handle a higher load.

“What’s going to make or break Brazos is our success. It’s not where we did or didn’t set an additional unit at a compressor station, so let’s have the excess capacity to manage the spikes in growth as it comes,” he said.

Flaring often happens when the pipelines or processing plants are unable to handle the excess load when gas continues to be pumped on the line even when it’s not flowing fast enough. Flaring will generally first appear on some of the older pipeline networks with older polyplastic pipes or aging compression units. Companies with more time in an area often have to deal with older material stretched out over millions of acres.

As a relative newcomer to the Permian, Brazos has the advantage of building its networks with steel pipe and new units. It’s one of the company’s selling points to potential customers.

“You’re not going to see a 20% to 30% line loss on our system, you’re not going to flare multiple times a week,” Luskey said.

For the basin as a whole, producers hope a new pipeline will allow them to lower the line pressure completely.

Lines of egress

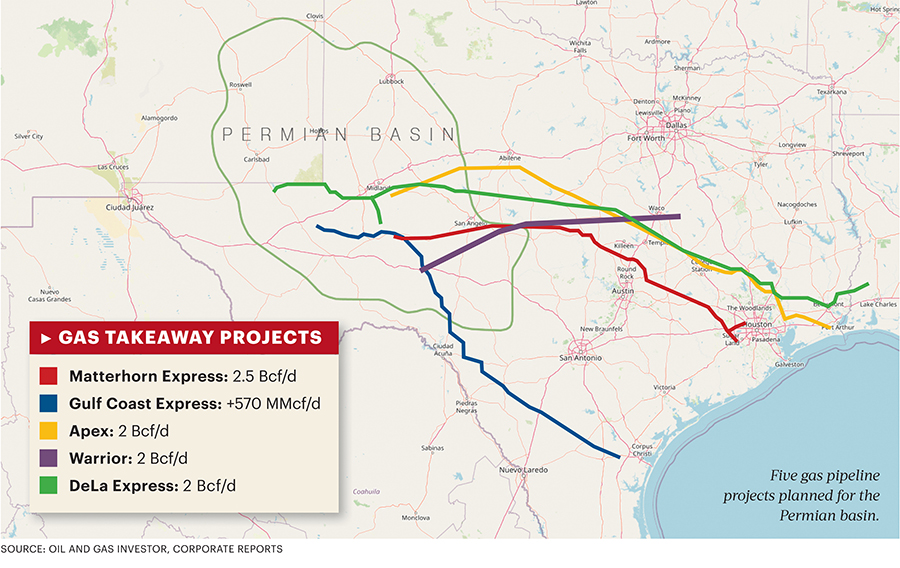

There are five major pipeline projects slated to take natural gas out of the Permian and onto different destinations on the Gulf Coast.

The Matterhorn Express, a joint venture by EnLink, WhiteWater, Marathon Petroleum and Devon Energy reached FID in 2022 and is currently the only project under construction. The 580-mile pipeline was designed to handle 2.5 Bcf/d of natural gas and terminates close to Houston. The line is expected to be in service before the fourth quarter.

The arrival of the Matterhorn will give Permian producers some breathing room, but not much, and not for long. The pipeline is expected to be at full capacity before the end of 2025, as natural gas production in the Midland and Delaware continues to increase with time and with increased exploitation of the area.

The other projects publicly proposed are:

- The Gulf Coast Express expansion, proposed by Kinder Morgan, would add 570 MMcf/d to an already existing pipeline that terminates in South Texas. Kinder Morgan called an open season on the project in May 2022 in hopes of implementing the expansion by December 2023. However, no FID on the project has been announced. In January, Kinder Morgan CEO Kim Dang said the company was still interested in the project.

- The Apex Pipeline is a proposed 563-mile, 2 Bcf/d capacity greenfield project that would terminate near Port Arthur, Texas. In March 2023, Targa received Texas Railroad Commission approval for the line. Company executives have publicly stated that they are still deciding if the project will move forward.

- Warrior Pipeline would run from the Permian to other Energy Transfer pipeline connections southwest of Forth Worth, Texas. The plan has the advantage of utilizing underused pipeline capacity in the Dallas/Fort Worth area and would have between 1.5 Bcf/d and 2 Bcf/d capacity. Energy Transfer says the pipeline could be completed within two years of FID, which it has not yet reached. Company co-CEO Tom Long said during the company’s first-quarter earnings call that the company continued to work on the project and would reach a decision about whether or not to go forward “pretty quick.”

- The DeLa Express project became public in April when private company Moss Lake Partners filed preliminary paperwork with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. The proposed 690-mile pipeline would have a capacity of 2 Bcf/d. It’s the only pipeline that would cross state lines, as the terminal point is slated for Cameron Parish, Louisiana. The pipeline is also the only one designed to haul liquids-rich gas, meaning that shippers could bypass processing in West Texas before shipping. According to its filing with the FERC, Moss Lake has projected a 2028 start date.

Ready to move?

Continental Resources President and CEO Robert Lawler said there will be a definite need regardless of whether the other proposed projects go forward.

“With the continued investment in oil in this basin, that need for additional capacity is going to continue to grow,” Lawler said. “And without the additional capacity, we are going to limit not only the gas for production but the oil production that the United States and the world need.”

Inside and outside of the Permian, much of the industry has been waiting for a natural gas boom.

In the next two years, North American LNG exports are expected to more than double from their present capacity of 11.4 Bcf/d to 24.3 Bcf/d, according to the EIA. Along the Gulf Coast, companies are constructing multiple LNG export terminals, which the Permian is expected to feed.

More recently, the connection between artificial intelligence (AI) and gas-fired generation has become known throughout the energy industry. TC Energy’s COO Stanley Chapman said during an earnings call that data center power demands could call for an 8 Bcf/d increase in natural gas production, equal to 21% of current natural gas demand in the U.S. for electrical production.

Data centers housing AI servers require far more electricity than typical servers, as AI chips use much more energy in their functions than normal chips.

Others in the gas industry have reported a surge in energy demand from “reshoring,” or when a manufacturing company moves its operations back to the U.S. after moving them offshore. Forbes reported in January that 69% of U.S. manufacturers are reshoring their operations.

Lawler said the growth projections are strong enough that some companies have become more aggressive in their project decisions. The trend could potentially encourage a midstream company pondering a major pipeline project.

Historically, companies have looked at a base of about 75% before announcing FID. With the long, steady growth in the Permian, that may no longer be necessary, he said.

“What’s interesting about this production path and the certainty that we have around it, is that recently on some project FIDs, folks have leaned into a lower commitment base,” he said. “With this certainty, we see it where we think the midstream company should have a better line of sight to those pipes being full and that FID should occur sooner.”

Recommended Reading

GA Drilling Moves Deep Geothermal Tech Closer to Commercialization

2025-02-19 - The U.S. Department of Energy estimates the next generation of geothermal projects could provide some 90 gigawatts in the U.S. by 2050.

Black & Veatch to Build Two Battery Storage Projects in UK

2025-02-11 - Serving as the projects’ owner’s engineer and technical advisor, Black & Veatch will review and provide technical advice, construction monitoring and schedule tracking services.

Ørsted, PGE Greenlight Baltica 2 Wind Project Offshore Poland

2025-01-29 - Ørsted said Baltica 2 is expected to be fully commissioned in 2027.

Energy Transition in Motion (Week of March 21, 2025)

2025-03-21 - Here is a look at some of this week’s renewable energy news, including a move by U.S. President Donald Trump to boost domestic production of critical minerals.

TotalEnergies, STMicroelectronics Ink 1.5 TWh Renewable Power Deal

2025-01-28 - As part of the 15-year contract, TotalEnergies will provide solar and wind power to New York-based STMicroelectronics.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.