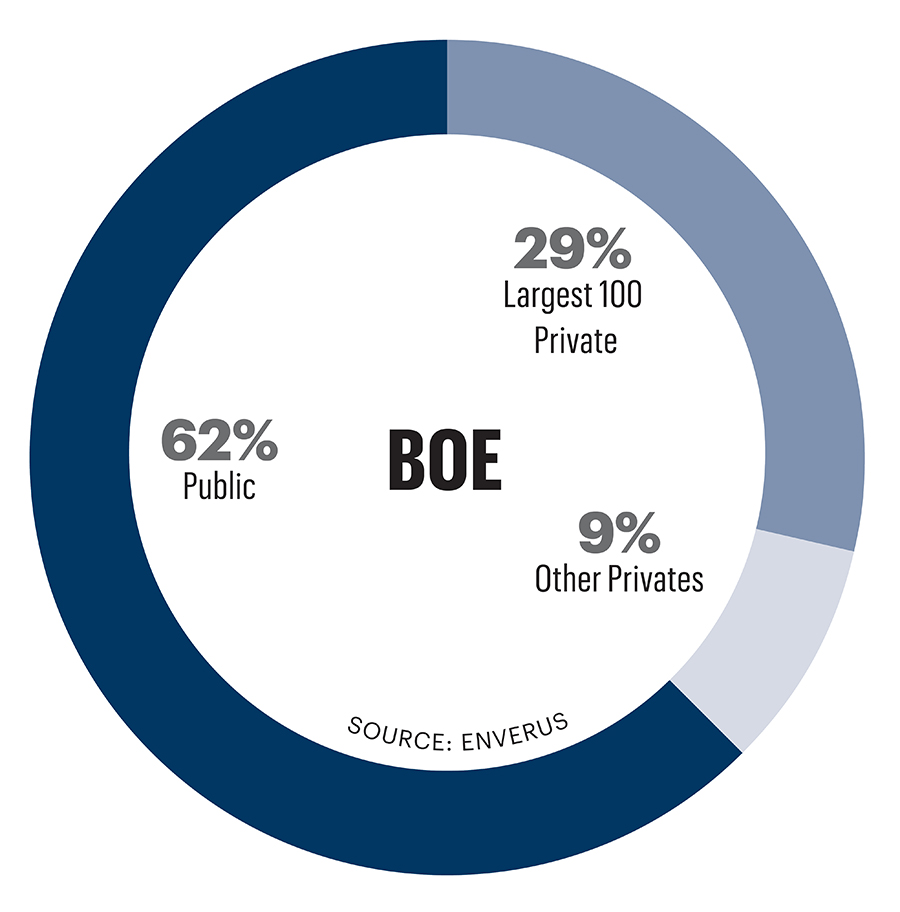

Massive consolidation sweeping across the E&P space has reshaped the landscape. Large public companies merged with larger public companies and private operators, which produce roughly 40% of U.S. supply, were swept up in the frenzy.

But don’t count out the private producer space.

“We’ve had too much fun doing what we did over the last 20 years,” Robert Anderson, Earthstone Energy’s former CEO, told Oil and Gas Investor (OGI).

In a cyclical industry as capital-intensive as oil and gas production, M&A is a fundamental mechanism of the business machine. But in a relatively short period, recent consolidation has removed key legacy producers, both large and small, from the field. Large companies beget larger companies. Old-time wildcatters have handed over the reins. And some private equity firms ran out the clock on their holdings.

Private E&Ps have been party to 169 sales since the beginning of 2023, Andrew Dittmar, senior vice president at Enverus Intelligence, told OGI. That doesn’t include mineral deals and it’s not all necessarily corporate mergers; some are simply assets that changed hands. It’s tricky to fully tabulate everything in the private world.

Still, it adds up to $78.3 billion and total associated production of 1,774Mboe/d worth of private transactions within 20 months.

Indeed, the opportunity to sell is significant.

While industry leaders’ basic instinct is to insist that oil and gas is here to stay, that bravado has been tempered by concern that current inventories won’t be enough to meet projected demand. A rush for the dwindling sets of available top tier assets now includes a sentiment that, with the right technology and enough stamina, the industry can enchant assets that are close-enough-to-core from mere pumpkins into royal carriages.

The consolidations have happened so swiftly that four of the top six private producers listed in the July edition of OGI are either waiting for their sales to close or no longer exist:

- Diamondback Energy bought Endeavor Energy in February 2024 for $26 billion;

- Occidental Petroleum acquired CrownRock, a joint venture of CrownQuest Operating and Lime Rock Partners, in December for $12 billion;

- Devon Energy grew its Williston footprint with the purchase of Grayson Mill Energy in July 2024 for $5 billion; and

- California Resources merged with Aera Energy to become California’s largest oil and gas producer in July 2024 with a $1.1 billion deal.

The M&A craze has created a void in the upstream sector once filled by the small, private companies that tend to drive innovation.

So, what’s next?

Despite lingering underinvestment in the space, commercial banks, regional banks, private equity firms and family offices say they’re open to the oil and gas business. And by virtue of M&A, there are plenty of displaced executives who are ready to start over.

“But it’s not all easy; there’s a lot of hard work,” Anderson said.

At 62, Anderson certainly had the option of retreating to his “honey-do” list when Permian Resources bought Earthstone Energy for a cool $4.5 billion in December.

Turning over the chief executive role at Earthstone didn’t mean he wasn’t ready to take on another one. Indeed, when Anderson spoke with OGI in early 2023, he expected Earthstone to be on the buying side of the impending M&A cycle.

Instead, this spring Anderson opted to create a new business called Petro Peak Operating with a handful of other Earthstone executive refugees, including former COO Steve Collins.

But this time, the business plan is different.

“What I don’t want to do is build myself out of a company. I want to build a company for the long haul, and it doesn’t have to be a gigantic public company,” he said. “What we want to do is build something that is more distribution, yield-driven and cash-flow generating to have a legacy long-term business that can be passed on to the next generation of Robert Andersons or whomever it is behind us.”

The different business plan means the investor set may differ, too.

While Anderson has had great success with private equity, the traditional quick exit strategy doesn’t necessarily align with what he wants for Petro Peak.

“We need to attract or look for different investors,” he said.

Enter the family office financing phenomenon that has become a common refrain in 2024 deal-making discussions. The wealth of these high net-worth individuals may originate in industries such as health care, insurance or aviation, but they are increasingly attracted to the oil and gas industry’s rate of return.

Gaining entrance into the private world of this selective group takes time. Still, Anderson said, Petro Peak is making some headway and he’s already established a relationship with one family office, the Vlasic Group, which has been a source of capital for both Earthstone and Oak Valley Resources, a private producer where Anderson was CEO prior to its merger with Earthstone in 2014.

Petro Peak will avoid the “knife fight for acreage” in hot spots such as the Haynesville Shale or the Midland and Delaware basins, where the build-and-flip model still reigns.

To make his case, Anderson is taking Petro Peak to conventionals and mature plays like the Central Basin Platform and the Eastern Shelf in New Mexico.

“Those are all fair game for us. And then conventional assets anywhere in Texas, and I’d put East Texas gas in there that’s not Haynesville or the Western Extension, then up into the Midcontinent,” he said. “There’s great historical fields that have been undercapitalized and maybe sort of avoided or just haven’t had the time and attention put on it by other companies. We think we can operate a little cheaper and a little more efficiently and get a few more barrels out of the ground or a few more MCFs out of the ground and just operate better and improve margins and drive returns for our investors that way.”

Over time, Eagle Ford, Bakken and even Midland Basin assets will mature and be viewed as non-core by consolidated companies. That’s the next cycle of M&A, Anderson said.

“It’ll be startups that are folks coming out of the Pioneers, the Endeavors and changing their strategy and staying away from these hot plays, but looking for the new areas,” he said. “That’s what this is all about. How do we create the next round of innovation? Where is the industry going with all this consolidation? Exxon isn’t going to own everybody.”

Capital X

As is the case with most oil and gas dealmaking, these transactions are composed of several moving parts. A relatively consistent oil price maintained over time gives the market some confidence, Jason Reimbold, managing director for energy investment banking at BOK Financial Securities, told OGI.

“We have started to see banks increase their appetite for exposure to oil and gas loans again,” he said.

Several factors are at play. ESG fervor has calmed down during the last year. The upstream sector’s rate of return rivals that of most other industries listed on the S&P 500. And many E&Ps have managed to pay off and pay down loans.

Banks are “now looking to at least maintain, if not grow, the loan portfolios,” Reimbold said. “We have started to see some competitive pressure on rates for loans in the market simply because there are more banks now pursuing these lending opportunities,” despite current interest rates.

Large commercial banks with long interest in the space are also watching for the next set of E&Ps, said Jeff Treadway, senior vice president and director of energy finance at Comerica.

“Almost every bank that’s in the energy business is very interested and eager to find new opportunities to fend off all of the deals that we’ve had pay off and go away,” he told OGI. “Commercial banks, specifically, they all want grow loans; it’s just what banks do. So, we’re trying to make those businesses. We really like the energy industry. We really love the upstream and midstream subsector of it, and so we are trying to find opportunities wherever we can.”

Ongoing global population growth and economic progress will make the Lower 48 the main provider of hydrocarbons to the global economy for several reasons, Marc Graham, Texas Capital’s head of energy, told OGI.

Domestic operators have a relatively low cost of production; they work in a politically stable environment; and the Lower 48 is one of the few jurisdictions where producers are taking steps to not only decrease their carbon footprint, but also making strides in carbon capture, usage and storage technologies, he said.

“I believe we will continue to expand where hydrocarbons are produced in the Lower 48,” Graham said. “And the expansion of plays isn’t necessarily the space where large, publicly listed companies will experiment.

“New companies will be formed to turn second tier assets into first tier assets, which is the second reason I am optimistic about the formation of new E&Ps in the Lower 48. Investors sit along a spectrum of risk/return trade-offs. The investor who wants exposure to the potential upside of discovering the next new play doesn’t want the return presented by the stability of a large publicly traded, dividend-paying company. So, new companies will be formed to push the boundaries of the current basin maps and experiment with new technologies and everywhere along the spectrum of potential returns.”

In some instances, it will be management teams of the companies that were absorbed by consolidation. Other emerging leaders will be the up-and-comers who’ve been waiting for an opportunity.

“There certainly are management teams that are going to continue on, albeit it is just a part of business. We will see some people leave the sector altogether. However, I think it’s going to require both to be successful,” Reimbold said. “There’s always going to be a need for highly experienced professionals, especially in such a highly technical sector. At the same time, there’s a need for new professionals to help build these businesses, then take them forward.”

The historic underinvestment in the space is where opportunity may be found.

“There simply are going to be more opportunities to build companies than there will likely be people to [work] in those companies. That’s not a bad spot to be in if you happen to be one that’s in the business,” Reimbold said.

The funding behind the founding of those new firms may take on a different look, he said.

“I think that we very well may see more direct investment that would be groups that possibly were LPs of larger funds in the past, [that are] now backing management teams individually or bringing on people to manage investments for them.

But there will always be a role for private equity, Reimbold said.

“Debt financing, given its structure, is only going to provide so much. Truly equity is going to remain a significant component to these financings. I expect some of that is going to come from what had become the household name traditional private equity funds,” he said. “And we may see new entrants to this sector as well, especially as we see an increase in deal flow and opportunities.”

The impact of interest rates on bankers’ engagement may depend on who you ask and the size of the transaction. Reimbold said that for the next 12 months or so, “the significance of interest rate cuts could not be overstated.”

But it won’t dictate whether lending happens.

“There’s not a question of if we move forward, of course we will move forward. But how we move forward and maybe at what pace will have something to do with the rate at which—no pun intended—but how quickly interest rates come down,” Reimbold said.

The acquiring companies during the record consolidation trend likely have billions of dollars’ worth of assets to sell. That’s a “hunting ground for new teams, management teams and people who were displaced as a result of these consolidations,” he said.

Interest rate relief, combined with stronger market valuations, could motivate those firms with ample non-core assets from their acquisitions to sell.

But meanwhile, most of the large public E&Ps have reduced their leverage to the point they don’t have to sell to pay down debt—especially if low valuations dictate asset price and high interest rates encumber potential buyers.

Several bankers stepped back from saying it would be a “wave” of emerging private producers. Consequently, the round of widely expected A&D activity may take longer to manifest.

“You’ll start seeing some deals around the edges, but it’s going to take time for Exxon to digest exactly what they have with Pioneer. It’s going to take time for Diamondback and Endeavor to really figure out [if] there are truly non-core things that they’re holding that [they were] just never going to get to,” Treadway said.

Discussions with some private equity teams indicates to Treadway that some “are just trying to peel off crust from these big deals, and it’s hard for them to get the attention of the companies that are in the midst of this M&A. But they are trying to—either through acreage trades or farm-ins—they’re trying to achieve little company makers.”

Private equity

But there is only so much private equity cash to go around in oil and gas. The amount available to the industry has diminished by up to 85% during the last five to seven years, Wil van Loh, founder and CEO of Quantum Capital Group, told OGI.

But Quantum is steadfast in the energy space and van Loh is busy. The private equity firm’s portfolio company, Trace Midstream Partners II, agreed in August to acquire New Mexico midstream company LM Energy Delaware, which was backed by another stalwart in the space, Old Ironsides Energy.

Private deal-making being private, though, the financial terms of the deal weren’t disclosed.

Van Loh is a big believer in the need for a new crop of E&Ps, too.

“It’s a really interesting position we find ourselves in because privates drove so much of the innovation in the shales. They drove so much of the growth of production. And as those assets migrate into the hands of public companies, you’re probably going to see less innovation,” he said.

Indeed, the so-called shale revolution was driven by the scale, technology and access to capital of the public companies in combination with the innovation, entrepreneurism and capital access of private companies, he said.

Private companies tend to be willing to take on more risk; public companies need predictability for their shareholders.

And some leaders of private companies that were sold to large enterprises still have work to do.

At the beginning of this year, Quantum Energy-backed Rockliff Energy sold to Tokyo Gas subsidiary TG Natural Resources in a $2.7 billion deal.

After 20 years and several businesses made in conjunction with Quantum, then-Rockliff CEO Alan Smith needed to step back and figure out what was next for him, an industry veteran “just a hair over 60” years old.

“After some discussion and strategizing and sort of working through what would be the appropriate thing for me to do at this juncture in life” with Quantum leader van Loh, Smith took on the executive chairman role of the June venture, Rockliff III, and a new spot at Quantum as an operating partner.

The team brought in a new CEO, Sheldon Burleson, a former top executive for strategy and planning at Chesapeake Energy, to lead the business in a direction that will differ from Rockliff’s previous iterations.

“We're probably going to shift a little bit. The Haynesville has been our backyard. That's what our team has done and certainly knows how to do that. We drilled over 300 Haynesville wells in Rockliff II, but that basin is more consolidated today,” Smith said.

Rockliff III’s direction will largely focus on the Eagle Ford, based largely in the expertise of the new team. Burleson was a key executive at Chesapeake when the company had a significant holding in the South Texas Shale play. And, Smith said, much of the Rockliff III team came from Petrohawk, which had a major presence in the Eagle Ford prior to selling to BHP.

“We just like that the fact that I don't think that Eagle Ford has been as consolidated. And we also like the different fluid windows. On the northern side of that trend line for the Eagle Ford, it runs literally from Louisiana to Mexico. North of that line is black oil, and then you go into a volatile oil, then you go into a retrograde condensate and you go into a wet gas and you go into dry gas. Those phase windows changed pretty rapidly,” he said. “So you can own a position we think potentially and have exposure to liquids and natural gas. That was intriguing to us.”

Recommended Reading

WTI Prices Fall as Trump Agrees to Pause Tariffs on Mexico, Canada

2025-02-04 - Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum said they had agreed to bolster border enforcement efforts in response to Trump's demand to crack down on immigration and drug smuggling.

Oil Prices Fall into Negative Territory as Trump Announces New Tariffs

2025-04-02 - U.S. futures rose by a dollar and then turned negative over the course of Trump's press conference on April 2 in which he announced tariffs on trading partners including the European Union, China and South Korea.

Oil Prices Extend Losses on Global Trade War, Recession Fears

2025-04-04 - Investment bank JPMorgan said it now sees a 60% chance of a global economic recession by year-end, up from 40% previously.

Envana Paints a Bigger Methane Picture by Combining Existing Data with AI

2025-01-28 - Envana Software Solutions, a joint venture between Halliburton Co. and Siguler Guff, has been awarded a $4.2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy to advance its AI methane detection solution.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.