Fiscally fit and price optimistic, many E&Ps reduced their hedging programs entering 2024 and are staying the course—even as conflict inflames the Middle East, Russia’s protracted war in Ukraine lingers and a U.S. oversupply of natural gas threatens to upend energy markets.

Three years of capital discipline and deleveraging have fortified balance sheets, boosting producers’ confidence that they can weather 2024 profitably with a smaller hedge portfolio or with no hedges at all, analysts say.

“Corporate debt is very low historically. Oil demand is growing,” Daniel Michalik, a Chicago-based associate director with Fitch Ratings, told Oil and Gas Investor (OGI). “Most producers are fairly comfortable with the relatively favorable macro environment.”

Hedging declined amid oil producers, which are seeing prices that generate steady profits, and gas-weighted operators, which saw U.S. prices weaken—and then collapse—during the first four months of 2024. An historic wave of E&P consolidation that began late last year remains on-trend. In many cases, M&A has reduced the risk that prompted previous hedges: The incumbent synergies of the pro forma companies boost those balance sheets, giving management confidence that they have the internal resources to cope with downturns.

A January report from the BloombergNEF energy data service indicates that shale producers have reduced 2024 hedge coverage on oil production to 13%, and natural gas to 31%. These levels are among the lowest recorded during the seven years that the data service has monitored shale hedging.

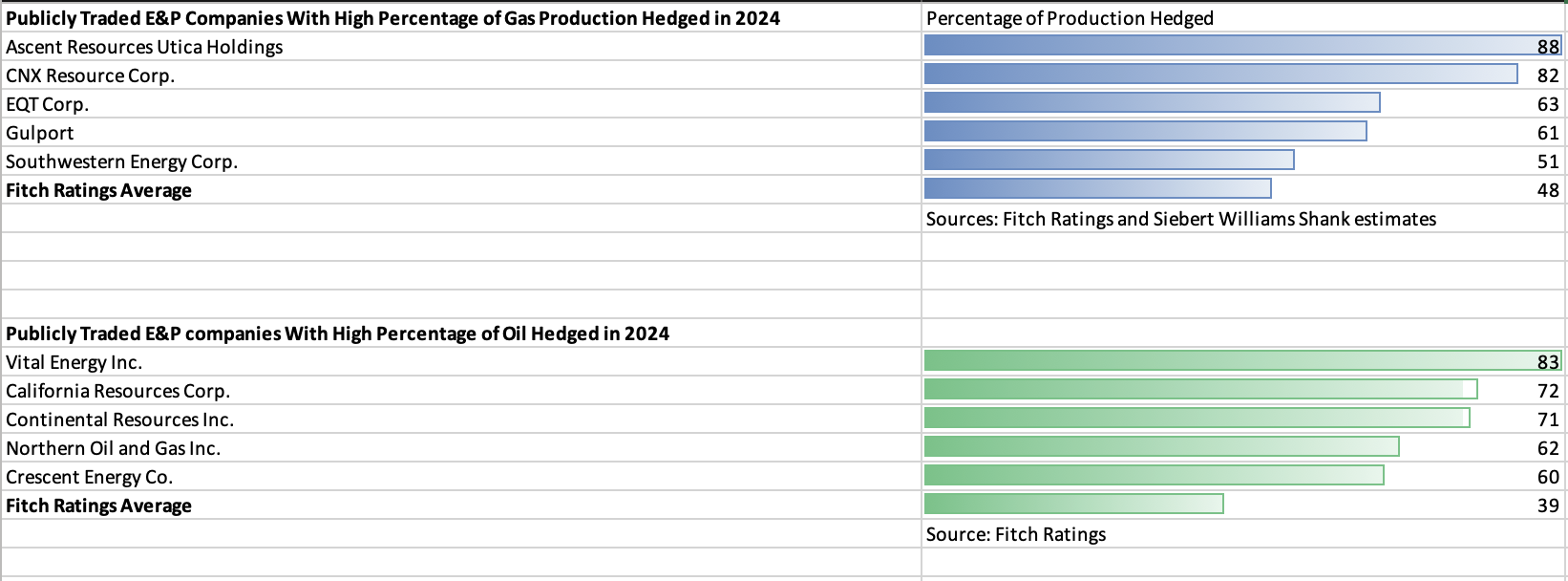

In February, Fitch analysts reported that, among its covered producers, oil-weighted companies hedged 39% of production and gas-weighted operators covered 48% of their production with hedges. Both represent significant decline across multiple years.

Producers are hesitant to switch up the strategy so far this year. Insiders say prudently priced natural gas coverage will remain out of reach unless prices rise significantly from sub-$2/Mcf levels, a movement that many analysts view skeptically.

Oil producers say that prices have a long way to drop before an expanded hedge portfolio would be worth the risk of missing out on the profits generated by reductions in supply or increased demand. Both WTI and Brent futures contracts have traded above $70/bbl since January 2022. While the April 30 WTI price of $82.70/bbl is down substantially from the 2022 average of $94.90/bbl, it remains well within the range needed to assure profitability across the industry, CEOs and analysts told OGI.

“Maybe a (sustained) environment of oil at sub-$50 a barrel” would prompt producers to expand their hedging activities, Michalik said. But market indicators suggest no one is anticipating such a dramatic slide in oil’s fortunes.

Geopolitical impact

The World Bank said in its April Commodity Market Outlook that it expects oil prices to increase this year because of rising geopolitical tensions and a tight balance between supply and demand. It projects the Brent crude price will average $84/bbl, up from its forecast of $83/bbl last year, with lots of upside potential if conflict intensifies in the Mideast or Europe.

“Further conflict escalation involving one or more key oil producers could result in extraction and exports . . . being curtailed, rapidly lessening global oil supply,” according to the World Bank report.

A recent Goldman Sachs survey of clients found most believe global politics pose the biggest risk to world economies—which generally results in upside for commodity prices.

After three years of oil prices averaging above $68/bbl, the value of the S&P Oil & Gas Exploration & Production Select Industry Index has more than doubled since August 2021, despite the sector’s struggle to recapture general investors. High-margin petroleum sales have left some investment-grade oil producers well-capitalized and secure enough to forgo the price security of hedging.

Large, integrated producers historically eschew hedging. They have the diversity to cover the downside and want exposure to upside pricing. Among oil producers with the strongest balance sheets, the sentiment resonates.

“If I hedge, I’m locking in what dollars we can receive, but I’ve also taken away exposure” to profits when oil prices rise, Chord Energy CEO Danny Brown told OGI during an exclusive interview.

Brown said he views hedging as a tool to either protect an expanded capital program or meet other goals such as keeping current on debt obligations. Echoing comments on strategy by other CEOs in recent weeks, Brown said Chord is spending to maintain current production, while sending money back to shareholders rather than investing in new drilling or borrowing to expand.

“As a result of that, I don’t need to protect my capital program. Our capital program is resilient down to much lower prices than it is right now,” he said.

Nor is paying down debt an issue at Chord, Brown said. “It’s not like we’re making a lot of interest payments to a bank.”

Chord’s balance sheet—and its ability to weather market vacillations—is based, at least in part, on its M&A strategy. The firm closed on its $4 billion acquisition of Williston peer Enerplus at the end of May.

Analysts say multibillion-dollar mergers like Chord-Enerplus are expected to contribute to further declines in oil hedge volume. Larger, fiscally stronger companies are more likely to shoulder the commodity price risk without hedging, which has the potential of locking out future upside.

Keeping the cash flowing

In the current environment, investors have pushed producers to avoid hedges and take the full benefits when prices rise. Investors want producers to generate maximum free cash flow to pay dividends and buy back stock, and producers are responding in kind, said Vincent Piazza, North American oil and gas equity analyst for Bloomberg Intelligence, an investment analyst group.

“You have started to hear more about cash flow yields and dividend payouts on (investor) conference calls than production growth,” Piazza said. “You don’t necessarily get better cash flow from putting more money into the ground. It can be a self-defeating strategy because the more you produce, the more the price goes down.”

Oil-focused executives increasingly express confidence that they can continue to divert free cash flow to stockholders and pay off or avoid debt while maintaining prudent production levels that don’t weaken oil prices.

Brown said Chord has the resources to finance its current capital program and pay cash to investors while leaving most of its production unhedged. The firm has hedged 13.8% of its crude oil production at a weighted average of $65.65/bbl for 2024, according to analysis by Siebert Williams Shank.

There is little room for hedging among the supermajors. Chevron has agreed to buy Hess Corp. for $53 billion and plans to eliminate Hess’ price hedges when it completes the acquisition. Pioneer Natural Resources closed out its hedges ahead of closing its $60 billion merger with Exxon Mobil, which, though it is cautiously expanding into energy trading, has not historically relied on oil price hedging to boost its bottom line.

The reduction in oil price hedging comes as natural gas producers that locked in prices for 2024 are expected to benefit greatly. A warm winter and steady production left U.S. storage facilities full, depressing prices nationwide.

“Gas storage is roughly 36% above the five-year average nationally, so we will have ample supply going into the spring and summer lull,” Piazza told OGI.

At the end of April, prices at the Waha Hub fell to negative numbers, making Permian Basin natural gas a costly byproduct of some oil producers’ efforts to maintain or expand oil output. Prices on the NYMEX for the June futures contract of natural gas hovered just under $2/Mcf at the end of April.

Depressed gas prices have made hedges prohibitively risky and expensive four months into 2024. “It makes no sense to hedge when gas is $2,” Piazza said.

Natural gas prices, which can be volatile because of their regional delivery limits and close links to electricity production, prompt gas producers to maintain more hedging even if that puts them at risk of missing out on price spikes.

That includes industry leaders such as Chesapeake Energy, EQT and Southwestern Energy. According to Siebert Williams Shank, Chesapeake hedged 59.9% of 2024 production at a price of $3.66/Mcf. EQT has 63.3% hedged at $3.96/Mcf and Southwestern has 52.8% hedged at $3.46/Mcf.

With prices under $2, gas-focused producers are using the prices contracted in hedges when they target cost-cutting and output goals.

Sabine Oil & Gas, a subsidiary of Osaka Gas USA, has hedged 80% of its production for the last three years, CEO Carl Isaac said.

—Chris Widell, CEO, Sponte Operating

“Our sales volumes today are equivalent to our hedge volumes today,” Isaac told a crowd gathered for Hart Energy’s DUG Gas+ conference this spring.

At current gas prices, some producers say unhedged volumes aren’t economic to produce.

“It’s just murder,” said Chris Widell, CEO of Sponte Operating. “We’re holding back our production to stay within as close as we can to hedge volumes” because “it’s just $1.70 gas.”

Matching expenses to hedging returns is critical because his company is still working to counter the surge in production costs that began after the COVID epidemic, Widell said.

Sponte is “drilling only when we have to,” and Widell estimates the company has cut costs by 20% during the last 18 months.

If they lack sufficient hedges going, natural gas producers can only wait for hoped-for developments such as significant increases in LNG exports and a surge in BTUs needed for electricity production this summer.

Andrea Passman, COO for Aethon Energy, said during Hart Energy's DUG Gas+ conference in March that the company considers its hedge book a key tool in its strategy of increasing cash distributions to investors and maintaining a strong free cash flow.

![“I think it’s well known that Aethon is a hedger. We like to lock in our returns as far out in the future as we possibly can [but] we’re really trying to figure out more what’s going on out there before we fully lock in those hedges.” —Andrea Passman, COO, Aethon Energy](/sites/default/files/inline-images/Andrea%20Passman.jpg)

—Andrea Passman, COO, Aethon Energy

Aethon, one of the largest private natural gas producers, is looking at hedges strategically after three years of acquisitions and 30% year-over-year growth. The company is now in “maintenance mode,” Passman said.

“Hopefully, we see some future price increases,” Passman said. “But I think ‘24 and ‘25 will probably look kind of similar, with 2025 showing a little more volatility, especially as volumes start to come up from” expected expanded LNG production. Aethon plans to adjust its hedges to reflect the effects of that volatility, once they become evident, she said.

“I think it’s well known that Aethon is a hedger,” Passman said. “We like to lock in our returns as far out in the future as we possibly can, [but] we’re really trying to figure out more of what’s going on out there before we fully lock in those hedges.”

While the largest companies may be able to go light on hedging, many small and medium-sized companies rely on debt to grow and build out projects, said Michael Corley, founder and managing director of, an advisory group that helps producers with their hedging strategies.

Companies with debt obligations “can’t just wait for prices to go up” to meet their commitments, Corley said. Hedging a portion of production can ensure that banks get paid while still letting exploration and development companies benefit substantially from price increases.

Swaps and other hedging tools can reduce the risks of regional transportation problems like those that led to negative prices for Permian gas, Corley said.

“Producers need price protection, especially if they are weighted toward natural gas,” Corley said. “You only have to go back to four years ago to where hedging was beneficial” to most producers.

Recommended Reading

Kimmeridge to Grow to 1 Bcf/d Via Bits and Bids, Including Haynesville

2025-03-31 - Kimmeridge Texas Gas expects to be producing nearly as much gas as its 1.3 Bcf/d Commonwealth LNG plant will export when it comes online in 2029, said CEO Dave Lawler.

Exxon Sits on Undeveloped Haynesville Assets as Peers Jockey for Inventory

2025-04-09 - Exxon Mobil still quietly holds hundreds of locations in the Haynesville Shale, where buyer interest is strong and inventory is scarce.

Exclusive: Kimmeridge's Lawler Avid for Eagle Ford's Dry Gas Window

2025-04-11 - Kimmeridge Texas Gas CEO David Lawler discusses the company's approach to doubling gas production to 1 Bcf/d and pending regulatory project approvals, in this Hart Energy Exclusive interview.

Improving Gas Macro Heightens M&A Interest in Haynesville, Midcon

2025-03-24 - Buyer interest for Haynesville gas inventory is strong, according to Jefferies and Stephens M&A experts. But with little running room left in the Haynesville, buyers are searching other gassy basins.

Aethon Dishes on Western Haynesville Costs as Gas Output Roars On

2025-01-22 - Aethon Energy’s western Haynesville gas wells produced nearly 34 Bcf in the first 11 months of 2024, according to the latest Texas Railroad Commission data.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.