The Renz No. 1 well in Washington County, Pennsylvania, was an abject failure, or so it seemed.

The year was 2003, and a little-known Range Resources geologist, Bill Zagorski, worked with the upstart producer trying to make vertical natural gas wells in southwestern Pennsylvania at depths of more than 8,000 ft, aiming for the Lower Devonian Oriskany Sandstone and the deeper Silurian Lockport Dolomite.

There’s a reason those formations aren’t household names, not even within the oil and gas industry.

“We already had a couple misses on here. We retired this well. They were literally ready to plug it, and then reclaim the location,” said Zagorski, who, spoiler alert, is now known as the “Father of the Marcellus.”

The idea was close to right, but the strategy and execution needed work. Around this time, Zagorski traveled to study a Floyd Shale prospect in Alabama. That effort was inspired by East Texas’ Barnett Shale, where the shale revolution remained in its infancy, and where Fort Worth, Texas-based Range had a limited acreage position. After all, Devon Energy had just bought the Barnett’s Mitchell Energy from the “Father of Fracking,” George Mitchell.

Then, Zagorski realized the Barnett Shale resembled the Marcellus Shale just above the Oriskany. The Marcellus depths had been explored before, but never with any commercial success.

“That really was my ‘aha’ moment,” Zagorski said. He told Oil and Gas Investor (OGI) he was filled with both excitement and fear. After previous misses, “I’m going to go back to them to say, ‘Hey, we’ve got to try this.’”

So, 20 years ago in October 2004, after returning to the failed well at the Renz farm off of Sabo Road in the Mount Pleasant Township of Pennsylvania, Range successfully fracked the well that would turn the Marcellus Shale into the largest natural gas-producing basin in the world.

This tiny, rural point in southwestern Pennsylvania—120 miles south from the famed Drake well drilled 165 years ago—helped move the shale boom into overdrive. In 10 years, Marcellus production had surged beyond expectations to nearly 14 Bcf/d. Today, the Marcellus produces more than 25 Bcf/d, and the combined Marcellus-Utica sits near 36 Bcf/d, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

With Range Resources remaining at the epicenter, the region is holding steady but poised to surge again to service the growing domestic power demand—on the uptick for the first time in decades—and the next wave of the LNG boom that’s currently under construction.

Under the current leadership of CEO and President Dennis Degner, who joined the company in 2010 and helped keep Range on the forefront of drilling and completions techniques before taking the CEO chair last year, Range could remain a core Marcellus leader for decades to come.

“Success begets success,” Degner said, and Range successfully jumpstarted a land rush throughout the Appalachia region. “A lot of other companies watched what Range did over the course of time and started to move from being a skeptic to a believer in unconventional shale development in Appalachia.”

Home, home on the range

Back in 2010, when Degner joined, Range was in full unconventional mode in the Marcellus, but Range averaged three frac stages a day with average lateral lengths of 3,000 ft. Now, Range is at an average of 9.5 stages daily with the mean length of laterals over 14,000 ft, and several exceeding 3 miles.

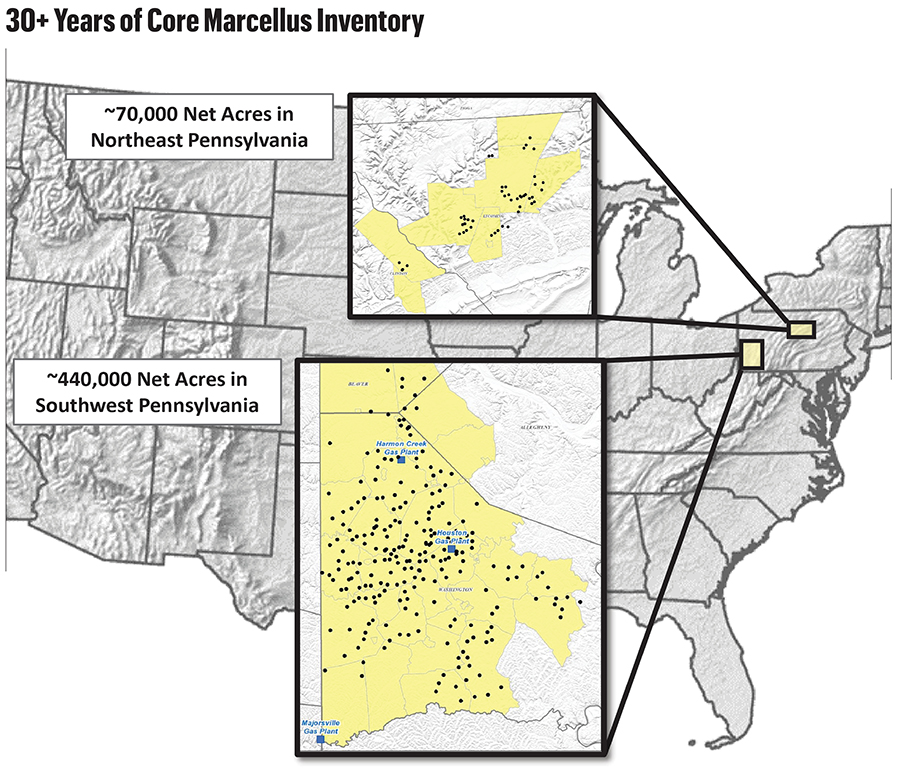

“From where I sit today, our focus is basically 100% on our Marcellus footprint,” Degner told OGI. He said, of Range’s over 500,000 net acres in the Marcellus, 87% of the lateral footage inventory has a breakeven of $2.50/MMBtu or less. “When you think about drilling 60, 70 wells a year, you can do this for over 30 years before you get to a Utica or an Upper Devonian.”

Longtime oilfield services analyst Jim Wicklund, now an investment banker with PPHB, remembers being amazed by the success of the Marcellus after many doubted its potential.

“The Marcellus has just been a giant home run from a technical point of view, from a gas supply point of view,” Wicklund said. “An upstart gas company, like Range, they were the ones riding the crest of the wave of natural gas. They had the cojones to be the first mover and take the risk.”

The problems for the Marcellus are not scientific; they’re political and regulatory, especially when it comes to pipeline permitting, he said.

“Between the Barnett and the Marcellus and the Haynesville [Shale], the Barnett is in decline, the Haynesville is higher-pressure gradient, and the Marcellus is just Goldilocks,” Wicklund said. “That has been a pleasant surprise: the size, the productivity. Now, if they just had access to markets.”

But it wasn’t all so obvious in 2004, not even after the eventual success of the landmark Renz well. And the Renz could have easily failed again without the right completion.

Because the Barnett is thicker than the Marcellus, common sense easily could have resulted in a smaller hydraulic fracture on the Renz, Zagorski said. Instead, new Range COO Jeff Ventura, who would become CEO in 2012, intervened in favor of a full, Barnett-style, slickwater frac.

“It’s probably the smartest thing anyone did on this because they took literally the most successful-sized Barnett frac, which is about 1 million gallons of water and maybe 350,000 pounds of sand, and they put that on our completion,” Zagorski said. “No gel, just slick water. And the frac went fine. And next day we got a flowback.”

The Renz started out at about 350 Mcf/d but quickly rose to 800 Mcf/d, he said, which was on the high end of a good Barnett vertical well.

It took Mitchell Energy almost two decades to find the right formula, but Range succeeded on the first slickwater frac try—the first Barnett-style frac east of the Mississippi. And Mitchell, Zagorski, Ventura and then-Range CEO John Pinkerton all deserve credit.

“Having the Barnett as a template, to basically pull off the shelf and use that as a guidepost template was incredibly impactful and helpful for us,” Degner said.

Home where the prospectors roam

Degner gives Zagorski a lot of the plaudits, calling him a “data junkie” and a “prospector at heart.”

“He was the guy who came forward and said, ‘Hey, this data that we’ve collected and what we’re seeing as an industry in the Barnett, I think we’re drilling through something that is a very strong analogue comparison to the Barnett, if not better,’” Degner said.

The Renz results were certainly promising, but they did not yet beget a boom.

After the flowback, Zagorski put together a pitch to Ventura to hire 40 land brokers to lease another 50,000 acres or so in Pennsylvania’s Washington, Beaver and Greene counties, as well as into the northern panhandle of West Virginia. Range ended up leasing more than double the proposal.

Zagorski projected the Marcellus as up to a 1 Tcf natural gas prospect. For context, in early 2008, Penn State University geoscientist Terry Engelder estimated the Marcellus’ natural gas reserves as 50 Tcf. He later revised it way higher to 392 Tcf in late 2008, and then to as much as 489 Tcf in 2009.

“There were times when we were looking at it and comparing the size of the Marcellus to the size of the Barnett and the Fayetteville [Shale], and we knew this thing was huge,” Zagorski said. “But we didn’t know it was going to be that big.”

Ventura kept encouraging Zagorski to “Just think bigger,” but it remained beyond his wildest dreams. “I was embarrassed,” Zagorski said. “I thought they’re going to throw me out. They’re going to think I’m crazy. Nobody could imagine the thing could have been that big.”

Zagorski thought they’d be able to lease land for $40 an acre. And they didn’t get a lot for less than $200 per acre. Once the land rush really kicked off in 2008, prices surged to $5,000 an acre and even higher later on.

At the time, the enthusiasm around the Haynesville in Louisiana was fading because of the exorbitant costs associated with the higher-pressure drilling and completions and, back then, the need for pricier ceramic proppants, Wicklund said. “We didn’t have LNG at the time. And so, it was like, ‘Screw this noise. Let’s go drill the Marcellus.’ And we did. And it was a giant land grab.”

But we’re not there yet. In 2005, the Marcellus was still pretty quiet as Range continued to build up its fortuitous acreage position.

Where the brokers and the geologists play

The equation that Range was yet to solve, though, was taking the full horizontal shale boom to the Marcellus with unconventional drilling and completions.

The initial horizontal well in the Marcellus that Range tried in 2005 produced less than the verticals. The second try in 2006 was a complete bust with zero gas production. And then a third, again, came in less than the verticals.

Range, in 2006, had already opened a regional Marcellus development office with a dedicated team and a capital budget of roughly $200 million to make the Marcellus economically viable—“low risk, high repeatability”—as desired by Ventura and Pinkerton.

Well, by 2007, Ventura told the team they’d spent three quarters of the budget, and the pressure was mounting. “He did not scold the team; he just encouraged us to figure it out,” Zagorski said.

At this point, with an admitted fear of failure and stress levels rising, Zagorski had his second “aha” moment.

Utilizing gamma-ray mapping and focused ion-beam scanning electron microscopy (FIB-SEM) imaging technology, the Range team charted the first few tries and realized the wells were producing better the farther away they were from the bottom or base of the Marcellus.

In a 15-page memo, Zagorski essentially proposes moving the landing zone 20-30 ft. higher than the best of the initial horizontal wells.

“I send it to all the technical guys and say the next lateral we do is going to be the one,” Zagorski said.

The Gulla No. 9H well proved to be the breakthrough horizontal in the Marcellus, coming online at nearly 3.5 MMcf/d, comparable to the successful Barnett horizontals, and the Gulla lateral was only about 3,000 ft.

After one follow-up lateral failed, the next few were all incrementally more successful than the Gulla.

The Marcellus breakthrough had truly arrived.

“In the thrill of discovery and the challenge of finding something, there was no rule book on this. There was nobody to help you figure out how to frac it. You just basically had to figure it out on your own intuitively and use creative thinking,” Zagorski said. “All these scientists and experts said it can’t work. And you’re saying, ‘Yeah, it can work.’ You had to have the insight and the long-term dedication to it to try new things and make stepwise increments. There was nothing like it in my career, nothing like it.”

Degner summarized, “The company had quickly reached a point where the belief was, we’ve just got to go drill a horizontal. We’re at that decision point—that fork in the road. In order for this to be successful, we’ve got to move forward and we’ve got to drill a quality horizontal in a target that we feel gives us the best chance of success. And put our best completion on it, which we knew at that time was a Barnett-style completion. And that’s where we had our breakthrough.”

In December 2007, Range, as a public company with shareholders to inform, announced the newest U.S. shale gas play, reporting three new horizontal Marcellus tests that made 3.7, 4.3, and 4.7 MMcfe in their first 24 hours.

“By the seventh or eighth lateral, we were testing laterals that had 10 MMcf/d, which is way higher than anything in the Barnett,” Zagorski said.

The land rush was on and, in three years or so, the industry drilled more than 2,500 horizontal wells throughout the Appalachian Formation.

Critics had said the Marcellus was too thin and uneconomic to make work. They were wrong.

“It ended up down in southwestern Pennsylvania, we have the highest porosity and the highest perm (permeability) and highest TOC (total organic carbon) content all concentrated into a third of the area that they would have up in northeast Pennsylvania,” Zagorski said. “If you frac something that’s that concentrated, and if your frac is all concentrated, then it’s like mining low-grade coal versus high-grade coal. You’re mining and fracking something that’s much richer.”

Give me the hills and the ring of the drills

At the time, Range Resources was far from a Marcellus pure-play producer. Range was still expanding in the Barnett until at least 2008. And, in 2016, Range erred, in hindsight, by buying—and later selling during the COVID pandemic—Haynesville producer Memorial Resource Development.

Over time, Range was focusing more and more on just the Marcellus.

“The great thing about the Barnett isn't the production that it provided to Range during that timeframe or the financial benefits that came out of it. The benefit of the Barnett for Range was it became the analogue for us to then discover the Marcellus,” Degner said. “The Barnett really became the testing ground and that lab for us to collect data, and get comfortable with what unconventional shale development looks like. What does the rock quality look like? How do you get gas out of something that has picodarcy permeability?”

“We looked at what the opportunity set was for an Appalachia, and we said, ‘Hold on a second, we have half a million net acres in Appalachia versus the smaller footprint that we had here in the Barnett. Here’s the opportunity.’

“And it was large, contiguous and allowed us to think differently about starting almost with a clean sheet of paper-type development,” Degner said. “It’s the one thing as an industry that, as an engineer, we always wanted.

“We had that in Appalachia.” Once the successful horizontals came in, he said, “You could see the Marcellus had the ability to surpass the Barnett.”

Over the years, Range divested from non-core, non-Marcellus positions until becoming a pure play in 2020.

“You saw us go from a production level that was essentially zero out of the Marcellus to now over 2 Bcf/d equivalent today and being a top 10 NGL producer in the U.S.,” Degner said.

And the rich natural gas in the ground

Indeed, Range Resources has come a long way from drilling hundreds of shallow, small-volume gas wells in Pennsylvania from coalbed methane before, eventually, tackling the Middle Devonian Marcellus.

What we now know as Range started almost 50 years ago as Lomak Petroleum in 1976 in Ohio.

Then came the 1980s oil bust and, on the verge of bankruptcy, Fort Worth-based Snyder Oil acquired Lomak in 1988, bringing the company to the Texas headquarters it still claims today.

Starting in 1990, Snyder began to divest from Lomak, which, now in a better financial position, went on a buying spree, including Appalachian Exploration and Pittsburgh-based Mark Resources, which employed Zagorski. Those deals also set up the company with some of its legacy Marcellus positions. Pinkerton, who worked at Snyder, stayed with Lomak and became CEO in 1992.

Snyder was fully divested by 1995 and, in 1997, Lomak increased its Pennsylvania position by buying assets from Cabot Oil & Gas.

In 1998, Lomak and Domain Energy merged, finally adopting the Range Resources name, maintaining the Fort Worth headquarters, and keeping Pinkerton as CEO.

In 1999, Range formed a 50:50 joint venture with FirstEnergy Corp. called Great Lakes Energy Partners to own properties in the Appalachian Basin, and Range fully bought the Great Lakes JV out in 2004, further strengthening the Appalachia position.

And that brings us back to the Renz, the shale boom, and a focus on the geology and making smart economical decisions.

“When I think about what unlocked the Marcellus for us, it really started with that subsurface evaluation of, what does the rock quality look like? And, where do you land your horizontal? Where do you target within that section?” Degner said. “It was fascinating to see the changes in the perm and porosity, so to speak, through the respective core sections. It changed the way we started thinking about our landing targets.

“Over the course of time, our well performance continued to improve as we enhanced our geological models.”

The energy sector loves sports clichés, and Degner opted for mixed sports baseball and football metaphors.

“I feel like we're proverbially stuck in the seventh inning. That’s probably not a great way of describing it. But, it’s because we keep pushing the goalpost. So, I’m mixing sports now,” he said with a laugh.

The industry feels like it’s maturing, and then a new efficiency paradigm shift occurs that allows Range to unlock new inventory affordably, he said.

“When I was using rigs that can only drill 10,000 ft, I was approaching what I thought was the upper limit—maybe the ninth [inning],” Degner said. “But, now, I’ve got a rig that can drill 20,000 ft, so we move the goalpost in a way where it feels like the innings have gone backwards.

“We’re seeing that continual growth, whether it’s well performance, geological assessment or even our efficiency. I would say the two things that stick out to me most are that subsurface technical work that’s still ongoing today and completion design.”

And the place where the cash does flow

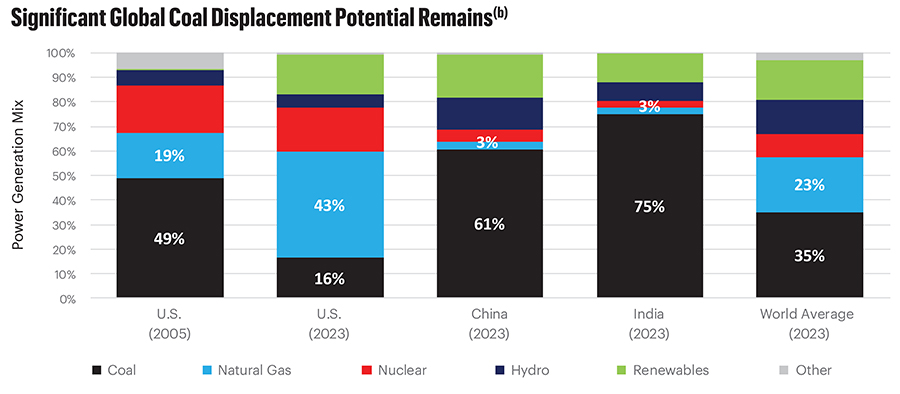

A victim of its own success, natural gas prices remain muted because production is so high while the industry awaits new LNG facilities and increased domestic demand from data centers and electrification.

Range is producing about 2.15 Bcfe/d, but that’s in the fourth consecutive year of “maintenance production mode” while operating no more than two drilling rigs in 2024.

That represents a stark contrast to the natural gas activity peak of 2008 when Range operated a whopping 33 rigs while averaging production of just 386 MMcfe/d by comparison.

For now, Range is keeping costs down, increasing efficiencies and remaining bullish for the longer term. Rivals keep expanding, but Degner is confident Range doesn’t need to acquire because of its vast, contiguous and untapped inventory. EQT Corp. keeps growing and Chesapeake just combined with Southwestern Energy to form the new, well, Expand Energy, which is now the nation’s top natural gas producer by volume.

“One of the reasons why you haven’t seen Range be as active in that M&A conversation is because of how much inventory we have,” Degner said. “It allows us just to continue to focus on our Marcellus activity and then push out higher-risk opportunities to decades down the road.”

That includes sitting on the deeper, costlier Utica and other formations in favor of sticking with the Marcellus for now, including holding off on exploring the Utica’s oil window for years to come.

And with greater efficiency and reduced debt, Range has reduced its hedging from almost 80% to just over 50% now to more than 30% in the year or two ahead, he said.

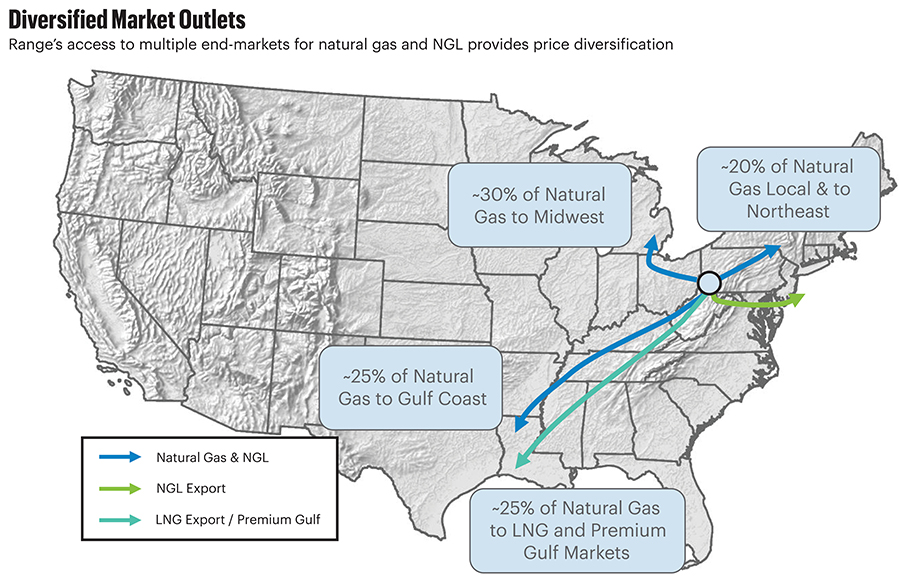

While the Appalachia region struggles with long-haul takeaway, even after the Mountain Valley Pipeline came online, the growth of data centers can increase regional demand. And Range feels well positioned with its existing infrastructure network of gathering and processing with MPLX, as well as its zero-vapor protocols for keeping emissions down, Degner added.

But incremental efficiency progress is critical, too, with more gains to be made in frac stages completed per day and on lateral lengths, which average close to 12,000 ft., he said.

“You’re rooting out non-productive time,” he said. “When we return to pad sites with existing production for a second wave of development, we traditionally see our efficiencies across the board improve about 30%.”

“And, now, we have somewhere in the neighborhood of right around 80 wells that are greater than 15,000 ft. Over the course of time, I’d expect us to continue to progress toward an average that could look like 15,000 ft,” he said.

Since retiring as vice president of geology, Zagorski has watched those gains with amazement.

“Once you had the combination of the longer laterals and the better, closer stage spacing combined with all kinds of cost efficiencies, that’s when you saw the metrics and the economics of the wells really drastically changed,” Zagorski said. “That’s basically what they’ve been doing over the last several years, just perfecting how to get more and more out.”

From an analyst perspective, Wicklund is confident more Appalachian takeaway capacity will be built because the demand will become too great, especially as U.S. LNG capacity more than doubled in the years ahead. The only question is the exact timing.

“You have a huge amount of pull on natural gas,” Wicklund said. “You’re going to have to increase gas production in the U.S. fairly significantly.

“It’s going to happen. It’s just a matter of pace. The Marcellus will get developed. It’s just the inevitability of demand.”

Recommended Reading

AI-Shale Synergy: Experts Detail Transformational Ops Improvements

2025-01-17 - An abundance of data enables automation that saves time, cuts waste, speeds decision-making and sweetens the bottom line. Of course, there are challenges.

Trump Administration to Open More Alaska Acres for Oil, Gas Drilling

2025-03-20 - U.S. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum said the agency plans to reopen the 82% of Alaska's National Petroleum Reserve that is available for leasing for development.

Energy Technology Startups Save Methane to Save Money

2025-03-28 - Startups are finding ways to curb methane emissions while increasing efficiency—and profits.

E&P Highlights: March 3, 2025

2025-03-03 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, from planned Kolibri wells in Oklahoma to a discovery in the Barents Sea.

Digital Twins ‘Fad’ Takes on New Life as Tool to Advance Long-Term Goals

2025-02-13 - As top E&P players such as BP, Chevron and Shell adopt the use of digital twins, the technology has gone from what engineers thought of as a ‘fad’ to a useful tool to solve business problems and hit long-term goals.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.