The Uinta battle started when a local group, the Seven County Coalition, attempted to build a new 88-mile railway out of the basin to improve crude egress. Railcars are the best option for transporting the Uinta’s waxy crude, which is too thick for typical pipelines. (Source: Shutterstock)

The U.S. Supreme Court begins its fall term on Oct. 7, and its decision on a proposed railway out of the Uinta Basin in Utah could have massive implications for energy infrastructure.

At issue is the environmental impact assessment energy companies must perform when building infrastructure. As the Supreme Court’s brief on the case puts it, the question is if the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) should require “an agency to study environmental impacts beyond the proximate effects of the action over which the agency has regulatory authority.”

In other words, should an environmental impact statement include only the pollution directly caused by a project, or also the pollution caused by the project both upstream and downstream?

In an analysis of the case, Arbo, a firm specializing in government regulation of energy infrastructure, said the ruling could affect the entire U.S. energy industry.

A broad interpretation of NEPA could lead to extensive, pricey and time-consuming environmental reviews that delay, or even derail, major projects, Arbo analysts wrote.

“Conversely, a narrower interpretation could streamline the approval process for infrastructure development, but might limit consideration of certain environmental impacts,” the analysts said.

The list of companies filing in support of the railway gives an indication of the decision’s importance to the energy sector.

Midstream company Energy Transfer, NextDecade LNG, 23 state governments, the Ute Indian Tribe, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and several national trade organizations have filed briefs supporting the railway project, according to the website SCOTUSblog.

Meanwhile, the Center for Biological Diversity, the Sierra Club and other environmental organizations have signed on to the brief against the project.

Mexican trucks

The argument boils down to an interpretation of a 2004 Supreme Court ruling, Department of Transportation v. Public Citizen, which involved hauling cargo across U.S. borders.

That legal battle started when the federal government decided to open up U.S. roads to Mexican truck traffic, as stipulated by the North American Free Trade Agreement of 1992. President George W. Bush directed the Department of Transportation (DOT) to drop an ongoing moratorium against Mexican hauling companies in 2001.

The DOT directed a sub-agency, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA), to develop safety standards for the trucks, which led to the first lawsuit.

Consumer advocacy group Public Citizen, leading a consortium of labor and environmental groups, petitioned the government to reject the new FMCSA law, partly because of the environmental effects the Mexican trucks would have on the American populace.

Instead, the court voted unanimously to allow Mexican trucks on U.S. roads, with Justice Clarence Thomas writing the opinion. The court ruled that the FMCSA, an agency concerned with safety, did not have the authority to consider the environmental impact of “indirect emissions,” according to a Tulane Law School study of the case.

After the president’s decision to allow Mexican truck traffic into the U.S., the Supreme Court ruled that the environmental effects of the extra traffic were not the DOT or FMCSA’s responsibility.

Complicating the issue, however, is the National Environmental Policy Act, which stipulates that federal agencies must study “any reasonably foreseeable adverse environmental effects which cannot be avoided should a proposal be implemented.”

Since then, U.S. district and appeals courts have disagreed on what “reasonably foreseeable” means for government agencies. The appeals courts have been split.

“Five circuits read Public Citizen to mean that an agency's environmental review can stop where its regulatory authority stops. Two circuits disagree and require review of any impact that can be called reasonably foreseeable,” the Arbo analysis said.

The U.S. Court of Appeals, D.C. Circuit’s, decision on the Uinta Railway is the case going before the Supreme Court.

The D.C. appeals court will be familiar with people watching the energy industry recently. Over the summer, the same court vacated three Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) permits. The court struck down NextDecade’s Rio Grande and Glenfarne’s Texas LNG projects, as well as Transco’s Regional Energy Access (REA) in the mid-Atlantic.

The court vacated the permits for reasons related to NEPA’s environmental impact statements, the same rules that tripped up the Uinta Basin railway project two years earlier.

Railway ties

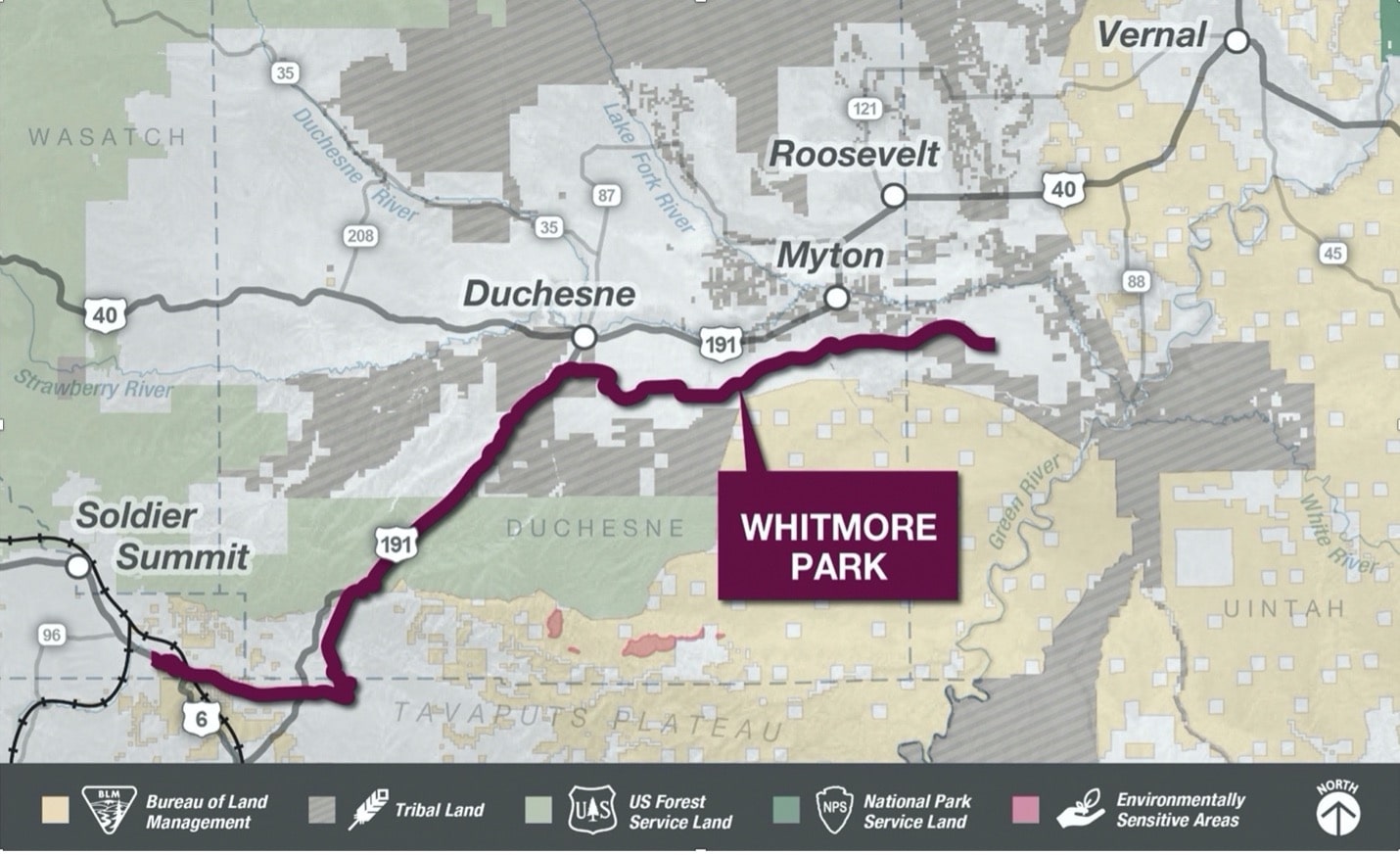

The Uinta battle started when a local group, the Seven County Coalition, attempted to build a new 88-mile railway out of the basin to improve crude egress. Railcars are the best option for transporting the Uinta’s waxy crude, which is too thick for typical pipelines.

The U.S. Surface Transportation Board (STB) approved the project, which then came under fire from leaders in Eagle County, Colorado. The case was brought before the D.C. appeals court, which struck down the STB’s decision, citing its interpretation of Public Citizen.

The court ruled that the STB, an agency tasked with regulating freight rail, should have considered the environmental impacts of increased crude production and refining. The case set off alarm bells in the energy sector, particularly with the later rulings from the D.C. court.

The petitioners “see the D.C. Circuit’s interpretation as turning agencies into ‘de facto environmental-policy czars,’ forcing them to consider impacts far beyond their expertise or authority,” Arbo wrote.

Court date

While the Supreme Court has chosen to hear the case in this year’s term, no date has been set for arguments. The case will not be heard until the winter, and a decision will most likely be announced until June 2025.

The Uinta Basin continues to expand output without the proposed railway. Crude output has seen rapid growth over the last few years, thanks to the growing availability of space on other train lines.

The final decision will, however, be watched closely by industry players across the U.S.

“A clear ruling from the Supreme Court on the scope of NEPA analysis could provide much-needed guidance for agencies, project developers and courts alike,” Arbo wrote.

Recommended Reading

Ovintiv Closes Montney Acquisition, Completing $4.3B in M&A

2025-02-02 - Ovintiv closed its $2.3 billion acquisition of Paramount Resource’s Montney Shale assets on Jan. 31 after divesting Unita Basin assets for $2 billion last week.

After Big, Oily M&A Year, Upstream E&Ps, Majors May Chase Gas Deals

2025-01-29 - Upstream M&A hit a high of $105 billion in 2024 even as deal values declined in the fourth quarter with just $9.6 billion in announced transactions.

Diamondback Acquires Permian’s Double Eagle IV for $4.1B

2025-02-18 - Diamondback Energy has agreed to acquire EnCap Investments-backed Double Eagle IV for approximately 6.9 million shares of Diamondback and $3 billion in cash.

Prairie Operating to Buy Bayswater D-J Basin Assets for $600MM

2025-02-07 - Prairie Operating Co. will purchase about 24,000 net acres from Bayswater Exploration & Production, which will still retain assets in Colorado and continue development of its northern Midland Basin assets.

Ring Energy Bolts On Lime Rock’s Central Basin Assets for $100MM

2025-02-26 - Ring Energy Inc. is bolting on Lime Rock Resources IV LP’s Central Basin Platform assets for $100 million.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.