Call it pipeline poker.

Some of the biggest names in the midstream business are seated at the table—Energy Transfer, ONEOK, Targa Resources and private company Moss Lake. The rules are simple: Whichever company can ante up with a final investment decision (FID) first wins.

Producers, analysts and midstream companies have predicted that another natural gas pipeline in the Permian will be needed before the end of 2026. A major pipeline generally takes two years to build. To meet the expected timeframe, an FID needs to be made so work can start during third quarter of 2024.

There are four major projects proposed, all pipelines with a projected capacity of at least 1.5 Bcf/d or more of natural gas. The players decide if and when it’s time to deal.

Filling the Matterhorn

At some point during summer, the Matterhorn Express Pipeline is set to enter service, probably to basin-wide celebrations in the Permian.

“We could see gas in there, probably as early as (July),” said Jason Feit, an adviser at Enverus. The line-filling and pressurizing process can take weeks. “It probably won’t be until September or October that it’s fully up and running, and those 2.5 Bcf/d are moving forward.”

Feit is the author of a report that studied the Permian’s natural gas pipeline capacity.

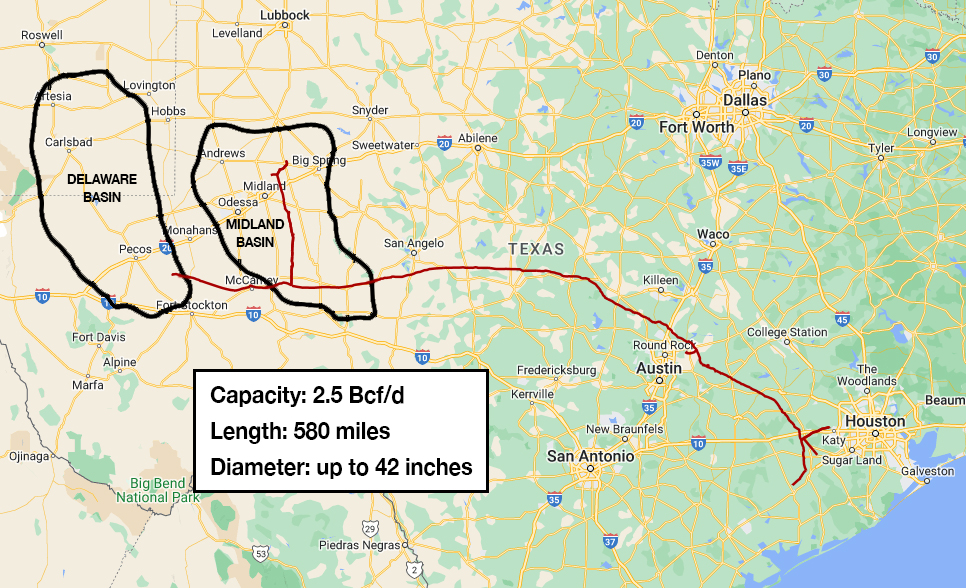

The FID on the Matterhorn Express, a joint venture among WhiteWater Midstream, EnLink Midstream, Devon Energy and MPLX, was made in May 2022. The project is a 580-mile, 42-inch diameter line going from the Permian Basin to Katy, Texas, near Houston.

Oil producers have been awaiting its arrival since summer 2023.

The Permian is the country’s second-most productive natural gas basin, behind Appalachia. Unlike Appalachia, the gas in the Permian is a byproduct, as producers are far more interested in the more lucrative crude business.

While gas production has fallen along with gas prices in other U.S. basins, the Permian’s natural gas output has continued to increase. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) reported that Permian gas production rose by 143 MMcf/d from April to May, at a time when prices at the regional Waha hub in Pecos, Texas, either hovered near or under $0, and when producers sought to avoid flaring access gas as much as possible.

Meanwhile, E&Ps in maturing parts of the play have watched their gas-to-oil ratios increase as the shale play matures.

Prices for WTI have stayed above $70/bbl for most of the last three years.

The natural gas pipelines out of the basin have been at or near capacity since halfway through 2023, even after two capacity expansion projects added 1 Bcf/d of extra takeaway capacity to the field.

Once the Matterhorn Express opens, a backed-up gas transport system will finally flow freely to demand along the Texas Gulf Coast.

Oil producers can bring up more crude, unworried about the associated gas that they were unable to get rid of previously. Prices at the Waha Hub may rise enough to provide gas producers with a noticeable profit.

And that freedom will last about 18 months, give or take. Then, the Permian’s expanding gas production will bring Matterhorn to capacity again, unless another pipeline is ready to take the growing load.

Volume, demand and timing

Feit said the midstream companies with new pipeline plans are more than likely focusing on behind-the-scenes work. It’s primarily a competition of lining up suppliers who are willing to buy capacity commitments.

“They’re all looking for long-term take-or-pay contracts for the pipe to justify the investment,” he said. “Obviously, they need gas to be committed to (the pipeline project) for more than a couple of years.”

The process can be tricky. Even though Permian producers have plenty of natural gas to ship, there are some reasons the shippers would be hesitant to sign a fixed-rate multi-year commitment for a fixed amount of capacity, RBN Energy analyst John Abeln pointed out in an April blog.

First, the people who agree to ship gas must worry about the price they commit to paying. Ideally, the shipper would commit to a price that was lower than the current spread between the gas supply point and the destination. The problem is that the current price may be too high because of a capacity bottleneck.

“When a spread is based on a bottleneck, and you fix the bottleneck, the spread collapses,” Abeln wrote.

Also, if a supplier’s natural gas production drops, the company could be contracted to pay for pipeline capacity it does not use.

Feit said, however, that the future market for natural gas along the Gulf Coast looks about as firm as it could.

“You’ve got obviously a huge buildout of 10 Bcf/d in the next few years of LNG,” he said, pointing to the many LNG export projects under construction along the Texas and Louisiana coasts. “Gas-fired power generation is a big demand. You’ve got [artificial intelligence], which is going to drive more demand.”

Feit said the development of solar and wind power is a wild card for the industry, as it’s difficult to predict how it will affect the development of power generation overall.

“But at the end of the day, the takeaway is there’s gas demand going forward, and it’s just going to grow materially,” he said.

Four-and-a-half pipes

As demand grows, the four proposals have different characteristics that Permian shippers may want to consider. None of the developers have reached FID.

ONEOK’s Saguaro Connector is designed to move 2.8 Bcf/d of natural gas from the Waha Hub to the Mexican border. It’s the shortest of the proposed Permian pipelines, but it would connect to a future pipeline in Mexico, which would then ship the gas to an LNG terminal on Mexico’s West Coast. The LNG project has yet to go to FID. The company said it would not go forward with the project until the LNG plant has reached FID.

In March 2023, Targa received approval from the Texas Railroad Commission to build Apex, a 563-mile, 42-inch diameter pipeline with an estimated capacity of 2 Bcf/d. The line would take gas from the Midland Basin to Port Arthur, Texas, near LNG facilities on the Texas and Louisiana border.

Energy Transfer proposed the Warrior Pipeline in 2022. The 260-mile project has an estimated capacity of 1.5 Bcf/d to 2 Bcf/d and would ship gas from the Permian to interconnects on Energy Transfer’s network south of Fort Worth, Texas. ET executives said in February that the pipeline has commitments for 25% of its capacity.

Energy Transfer also just acquired WTG Midstream in a $3.25 billion deal. WTG’s network, which is primarily east of the Midland Basin, would give ET an advantage in developing the pipeline, several analysts said at the time of the acquisition.

The DeLa Express is the newest proposed project for taking Permian natural gas. It’s the longest, at 690 miles. It’s the only proposed pipeline that would cross into another state, with current plans showing a termination at LNG facilities at Lake Charles, Louisiana. It’s also the furthest from any planned construction. Moss Lake Partners, the private firm planning the line, has a target construction start date in 2026.

Waiting to deal

With DeLa Express holding off, the other three projects will be worth keeping an eye on over the next few months, though midstreamer Kinder Morgan may play a wild card.

The company has proposed a 500 MMcf/d expansion of the Gulf Coast Express, a pipeline that already connects the Midland and Delaware basins to the area surrounding Corpus Christi, Texas. The expansion could happen rapidly, and its implementation could give the other midstream companies a “buffer,” Feit said, of a few months before making a decision with an FID on their larger projects.

Right now, the demand is a bit spread around between the projects,” Feit said.

“Someone just needs to step out in front and become the lead project. Then, more demand will flock to them, and you’ll get an FID.”

Recommended Reading

Q&A: Where There’s a Williams, There’s a Way for Gas

2025-04-09 - Midstream giant Williams Cos. leads the natural gas bulls on the great infrastructure buildout, President and CEO Alan Armstrong tells Hart Energy.

Phillips 66 Urges Shareholders to Vote Against Elliott at Annual Meeting

2025-04-08 - Phillips 66’s board of directors is again pushing against one of its largest investors—Elliott Investment Management—with a letter to shareholders detailing how to vote against the investment company at its upcoming annual meeting.

NRG’s President of Consumer Rasesh Patel to Retire

2025-04-07 - NRG Energy anticipates naming a successor during the second quarter. Patel will remain in an advisory role during the transition.

PE Firm Andros Capital Partners Closes $1 Billion Energy Fund

2025-04-07 - Andros Capital Partners maintains a flexible investment mandate, allowing the firm to invest opportunistically across the capital structure in both public and private equity or debt securities.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.