Diversification is the name of the game for all non-op companies. (Source: Shutterstock)

The fairly audible grumbling from non-operated oil and gas companies is that they don’t get their due on Wall Street.

Generally, they trade at a considerable discount to their E&P cousins despite generating consistent returns, carrying low debt and returning cash to shareholders—just like the E&Ps that get more investor attention.

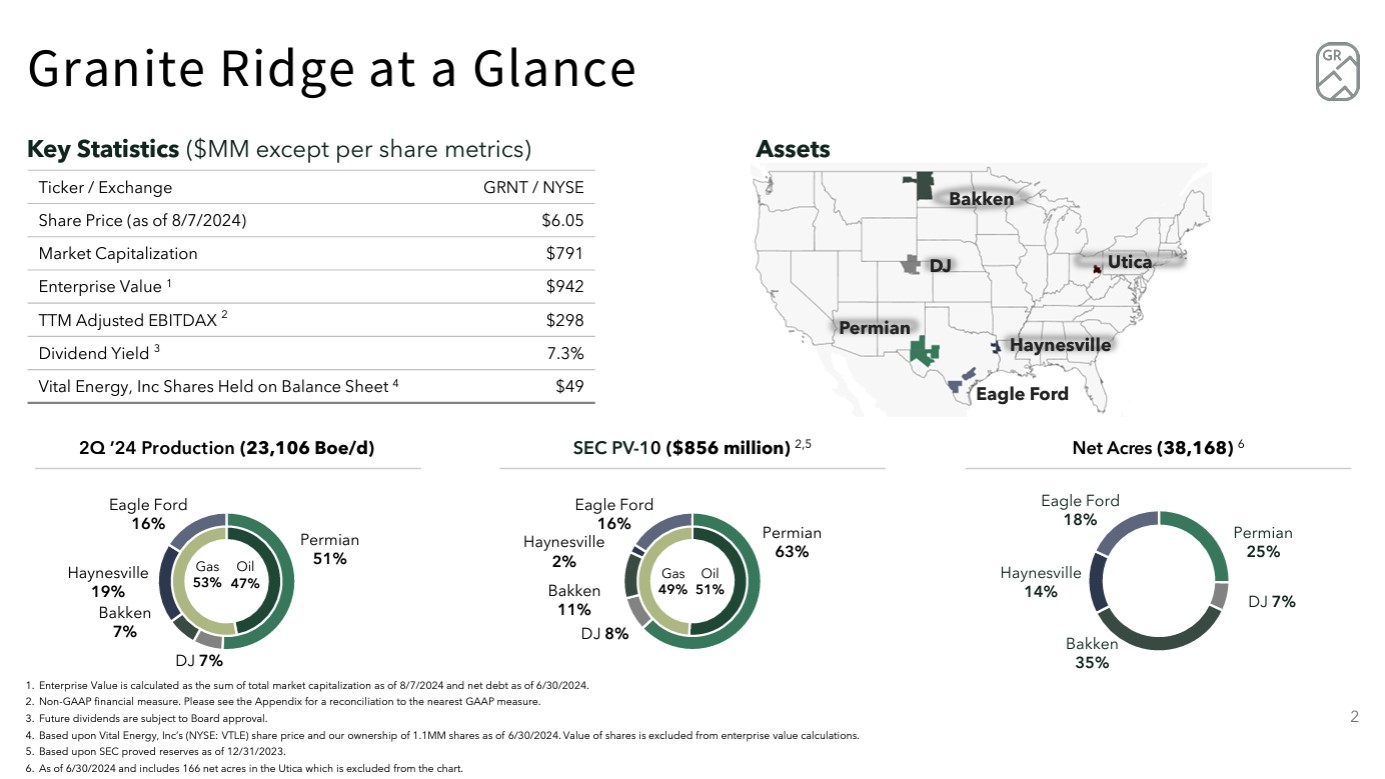

Granite Ridge Resources, for instance, offers a yield of about 7% but trades at a discount to operated E&P peers of 1.5x to 2.0x (and trails other non-ops by 0.5x).

That doesn’t mean non-ops lack a fan base. As EnerCom Denver came to a close Aug. 21, Megan Hays, a managing director and head of sustainable investment at Kimmeridge, lauded the not-so-niche sector.

“We think about $8 billion a year of capital is being spent on non-op,” Hays said. “And if people are going to get more critical over how they’re allocating it, that is going to continue to find its way to the sales process.

Granite Ridge’s figures present the equation slightly differently: Lower 48 operators spend about $100 billion in gross development capital annually. About 25%—$25 billion—of that spend is footed by their non-op partners.

The non-op model is not without its difficulties. For one thing it’s hard to define and, not unlike mineral and royalties’ companies, they often have to fastidiously ensure they’re in line or ahead of the operator’s drill bit. The non-op story is generally more procedural. Non-ops have a say in what E&Ps drill, to some extent, through authorizations for expenditure, known as AFEs. If a non-op passes on an AFE, the E&P can still drill, but without the non-ops’ cash participation. Non-ops’ other selling point: low expenses, particularly in overhead expenses.

The challenge for other non-ops—and simultaneously a core strength—is highly specialized diversification. Non-ops not only eschew homogeneity (although public non-ops are disproportionately investing in the Permian Basin)— they consistently cash in on wherever they’re at. But, again, they’re also beholden to operators to drill.

That’s led to a dilemma for some.

Granite Ridge, for example, is heavily invested in the Delaware Basin. But the company also holds interests in the Eagle Ford Shale, the Denver-Julesburg (D-J) Basin, the Haynesville, the Midland Basin and other areas where the goal is rate of return rather than building massive, congruous footprints.

“The main issue there is I think most investors view oil and gas companies as assets rather than businesses,” said Michael Ott, Granite Ridge vice president of corporate development.

However, Granite Ridge is in the process of changing part of its business model to function more like a capital partner, a kind of offshoot from more demanding or tight-pursed private equity firms. The effort comes as the company (and other non-ops) look to break out of the business model’s reputation as a mostly silent partner.

Northern Oil & Gas (NOG) has done so successfully in a simpler and sexier story—plucking down hundreds of millions of dollars in multiple deals the past few years.

NOG has found headline-stealing deals to attract investors. NOG is “the most reliable and consistent partner for the purchase and development of high-quality properties,” CEO Nick O’Grady said after one recent deal.

The remark came after yet another large-scale deal in which NOG played non-op financier. NOG has repeatedly engaged in deals with E&Ps, including SM Energy’s deal pending acquisition of Uinta producer XCL Resources for $2.55 billion. That was in June.

In late July, NOG was at it again with a joint bid with Vital Energy (the companies’ second partnership) to acquire Delaware Basin assets from Point Energy Partners for a combined $1.1 billion.

Not NOG

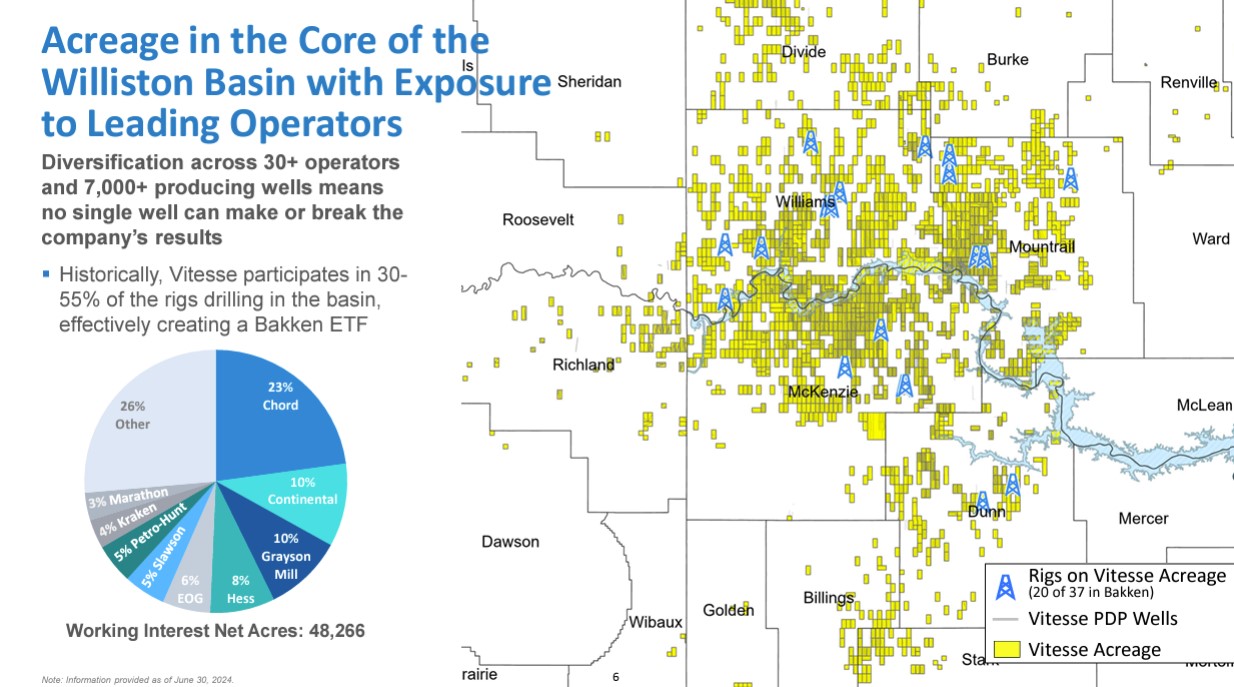

Vitesse Energy, by contrast, is a non-op deeply tied to the Bakken and Three Forks that seemingly seldom looks outside of the Williston Basin. The company’s holdings are spread across 7,018 (163 net) producing wells with an average working interest of 2.8%.

"We've looked at other basins," Henderson said. "We just know the Bakken the best."

In North Dakota, the company’s 50,000 piecemeal acres stretch north from Divide County, through the heart of Williams and south into Dunn County and beyond. Across that expanse, the company estimates it has more than 200 net remaining Bakken locations.

Vitesse CFO James Henderson, when asked if his company would consider some NOG-style tagalong deal, said the company simply isn’t in the “same class.” The company likes, knows, studied and built an entire proprietary analytical system around the Williston.

“Everyone wants to compare [them to Northern] but they’re way bigger, they’ve been around,” Henderson told Hart Energy. “We think we’ve developed something. What they’re doing is so different from what we’re doing.”

Besides, he said, opportunities continue to crop up in the Bakken. Devon Energy said in July it would buy Grayson Mill Energy in a cash and stock deal valued at $5 billion.

“The number of rigs in the basins doesn't really change a whole lot year to year,” Henderson said. “With consolidation, maybe we’ll see a little more [activity] as Devon and others bring more rigs to the basin. Or they’ll spin off their non-op and we purchase some of that.”

‘Hybrid’ non-op

Granite Ridge has recently started to head in a different direction.

Diversification is the name of the game for all non-op companies. Speaking at EnerCom, Ott noted that the company is diversified by basin, operator, commodity and private and public company.

Most traditional non-op work is the blocking and tackling ground game that Granite CEO Luke Brandenberg likes to call “burgers and beer”—the idea being that such deals are relationship driven.

So the company doesn’t particularly distinguish buying opportunities in the Delaware, Bakken or the Haynesville, as long as the return on investment materializes.

Notably, the company’s recent presentation included a new spot on its map: the Utica. However, Ott did not address the area other than to say, “we've got a new logo on that map as well, an area that we’re excited about in the Northeast.”

“We are not looking for PDP blowdown opportunities,” Ott said. “We are focused on drill bit activities, strategic partnerships.”

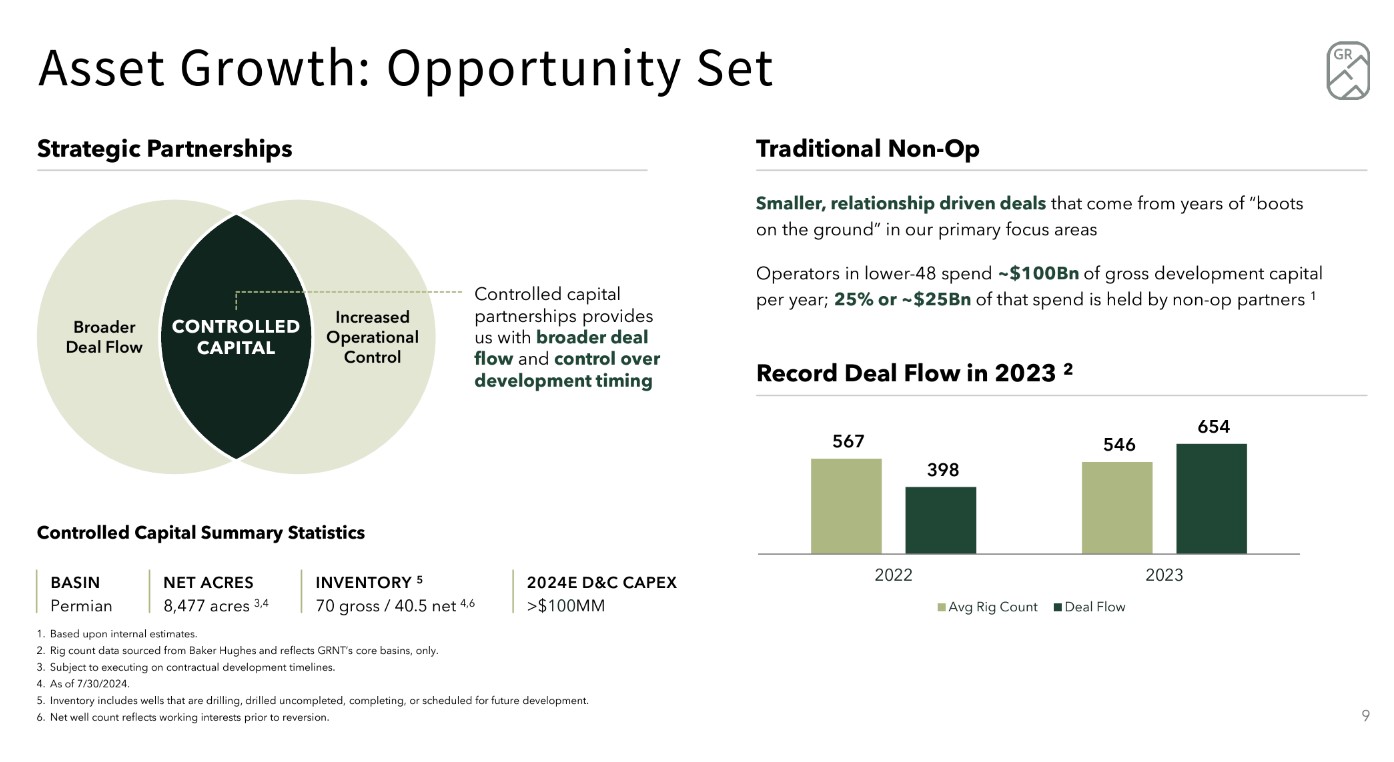

Granite has lately been moving into strategic partnerships—what Ott termed “a controlled capital program”—in which the company combines its relationships to increase our deal flow.

“But also as a non-op, we're trying to increase our control and the timing and development that we're investing in,” he said.

West Texas partners

Granite Ridge is involved in two new partnerships in West Texas, one focused in the Midland and the other in the Delaware.

Between the partnerships, Granite has accumulated close to 8,500 net acres with 70 gross (40.5 net) locations.

“In 2024, we're going to spend over a hundred million dollars with these partners on through the drill bit,” Ott said.

Granite’s controlled capital program essentially gathers up successful private companies who have “done the private equity mouse trap for a long time,” Ott said.

The teams were able to build a lot of value, gain experience and a proven track record but, because private equity fundraising has slowed, “that leaves a lot of teams on the sidelines with no committed capital.”

Granite has sought out those teams and created this strategy “where they have the same economic or very similar economic outcomes, except they can control their business. And we control development time and we control the approval of acquisitions.”

“We are more or less creating a hybrid operated wedge within our non-op company,” Ott said. “So we're trying to transition our company from being a traditional non-op company where things are lumpy. You don't control timing. You don't control things like spacing or what bench you're going to develop or how you're going to underwrite the investment.”

As a non-op capital provider, “we're able to call the shots a little bit.”

“Of course it's a working relationship, of course they have a say. But it's our ability to transition our portfolio from what is generally unpredictable in the non-op world to being more predictable,” he said. “It's going to prove our ability to provide guidance, craft our capital structure and have more predictable timing around the development and investment of our dollars and the merit of this.”

The ultimate goal is to make good returns, reinvest cash flow and “bridge that gap” between non-op and operated investment.

Ott said Granite’s strategy comes from a traditional non-op space that the public space doesn’t appreciate the same way they do operated players.

The company can’t do much about that, except to prove over time it’s able to generate new opportunities for the business to invest in.

“One thing we can do is what we're doing right now with transitioning our portfolio to our controlled capital strategy,” he said.

He added that in 2024, Granite will spend “north of a hundred million dollars with our controlled capital partners in West Texas next year.”

That represents about 40% of the company’s capital spend, while next year controlled capital spending will be more than 50% of spending.

“The company’s guided controlled capital production is going to be somewhere between 5% and 10% of our annual production next year,” he said. “We expect it to be a lot higher as we've invested a lot of money this year, but the operated side has much longer lead time than the non-op side, where non-op has tendency to come in at the last minute.”

Ott added that, on the operated side, “we picked up a rig with one partner in the Delaware Basin last October, and that first pad came online in June,” he said. “So as we roll through what we call the J-curve and start to invest those dollars, we're starting to see the fruits of that labor here in the second half of the year.”

Recommended Reading

Exxon Slips After Flagging Weak 4Q Earnings on Refining Squeeze

2025-01-08 - Exxon Mobil shares fell nearly 2% in early trading on Jan. 8 after the top U.S. oil producer warned of a decline in refining profits in the fourth quarter and weak returns across its operations.

Phillips 66’s NGL Focus, Midstream Acquisitions Pay Off in 2024

2025-02-04 - Phillips 66 reported record volumes for 2024 as it advances a wellhead-to-market strategy within its midstream business.

Rising Phoenix Capital Launches $20MM Mineral Fund

2025-02-05 - Rising Phoenix Capital said the La Plata Peak Income Fund focuses on acquiring producing royalty interests that provide consistent cash flow without drilling risk.

Equinor Commences First Tranche of $5B Share Buyback

2025-02-07 - Equinor began the first tranche of a share repurchase of up to $5 billion.

Q&A: Petrie Partners Co-Founder Offers the Private Equity Perspective

2025-02-19 - Applying veteran wisdom to the oil and gas finance landscape, trends for 2025 begin to emerge.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.