Currently, SAF accounts for less than 1% of total jet fuel used by airlines. Data from the IATA show production is increasing as some 140 renewable fuel projects with SAF production capabilities are expected to be in production by 2030. (Source: Shutterstock)

Political pundits see setbacks ahead for parts of the clean energy movement under Trump 2.0, but efforts to boost production and use of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) are expected to continue given international mandates despite some aviation industry worries.

One reason why: big oil players such as BP, Chevron, Eni and others are ramping up investments in biofuels with a focus on SAF and hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO). The renewable fuels can be blended with conventional aviation fuel without modification to existing planes or engines, lowering greenhouse-gas emissions (GHG).

Using feedstock such as waste cooking oil, municipal waste, seaweed or captured CO2, SAF is considered a key cog in emissions reduction strategies for the hard-to-abate aviation sector. High energy-to-weight requirements needed for flight is something heavy battery energy storage technologies cannot meet, so the focus has centered on sustainable fuels.

Countries in regions such as Asia and the EU are mandating SAF. Aviation is also a global industry subject to international laws. Efforts to boost SAF are likely to carry on under the Trump administration, according to Kevin Lewis, co-leader of law firm Sidley Austin’s aviation and airlines team.

“When we’re talking about SAF, we’re talking about solutions [that] involve the kind of infrastructure and jobs that Republicans generally and Trump seem to like,” Lewis said during a recent media roundtable in Houston. “So those are reasons why you might not see a de-emphasis of the focus on scaling up SAF reasons.”

To boot, Trump’s previous comments favor electric take-off and landing vehicles (think flying cars that take off and land like helicopters), he added.

However, SAF is not without challenges. For starters, there is not enough of the low-carbon fuel being produced, and high costs—compared to traditional fossil fuels—may quell airlines’ appetite despite a yearning to lower emissions.

Concerns, progress

SAF growth, as with other clean energy technologies, relies on government support such as tax incentives. Some aviation industry groups fear those are in jeopardy.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA), one of the signature laws of President Joe Biden’s administration, incentivizes production of SAF that lowers lifecycle GHG emissions by at least 50% compared with petroleum-based jet fuel. SAF producers are eligible for a tax credit of $1.25 to $1.75 per gallon, according to guidance released this year by the U.S. Treasury Department.

Trump, however, has vowed to repeal parts of the IRA and rescind unspent funds. That has the aviation industry nervous. Concerns were raised by members of International Air Transport Association (IATA) and American Airlines during an airlines industry conference Nov. 26 in London, according to Reuters.

“There are these big potential risks on what the Trump policy is actually going to be and how this really affects everybody’s motivation to pursue climate change,” Marie Owens Thomsen, chief economist for airlines trade body IATA, told Reuters.

Ronce Almond, American Airlines’ head of intergovernmental affairs, said “the market needs certainty in terms of building up their reservoir.”

Currently, SAF accounts for less than 1% of total jet fuel used by airlines. Data from the IATA show production is increasing as some 140 renewable fuel projects with SAF production capabilities are expected to be in production by 2030. If the projects proceed as planned, total renewable fuel production capacity could reach 51 million tonnes by 2030, the IATA said.

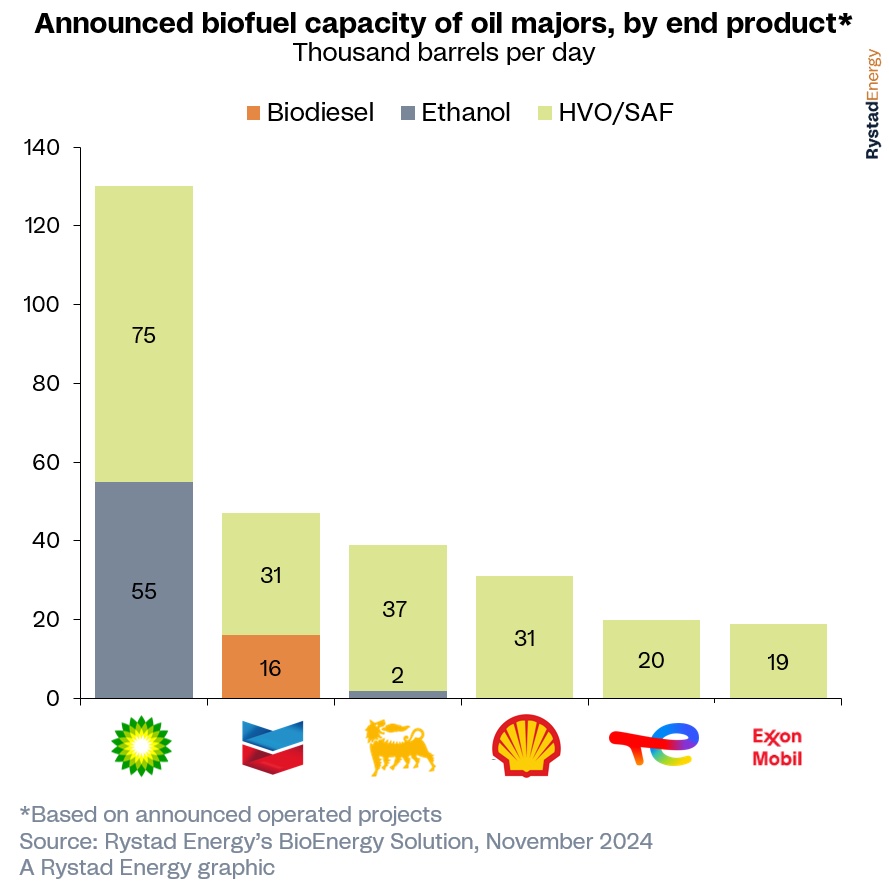

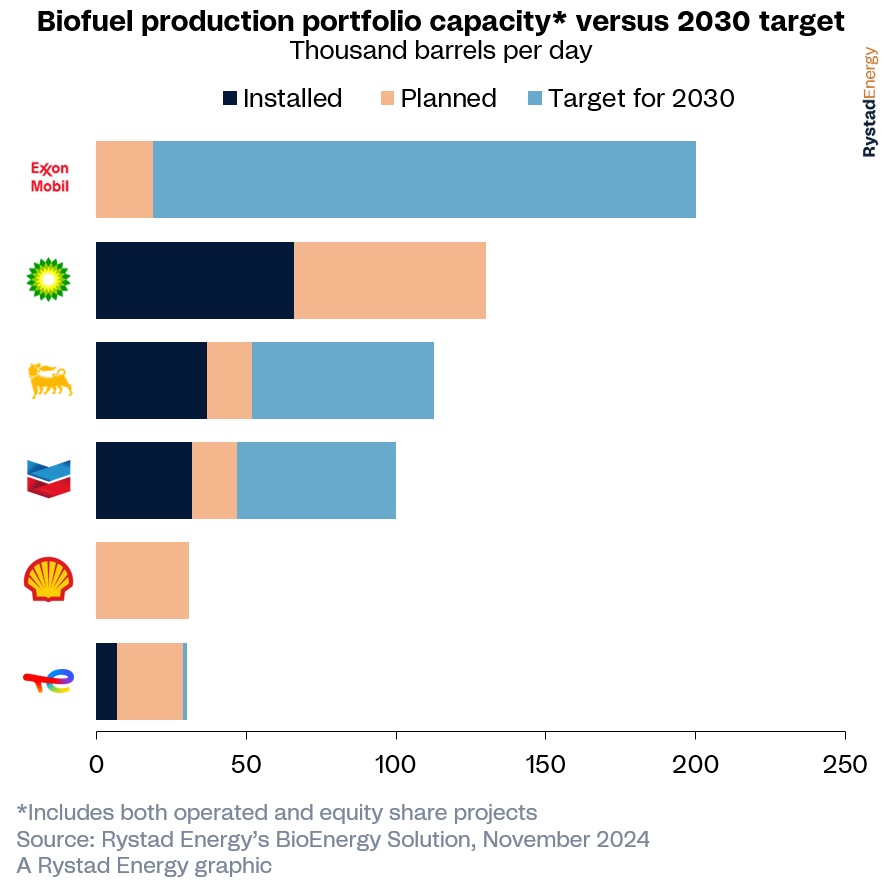

A report released in November by Rystad Energy show that six oil majors alone have announced 43 biofuel projects that are already operational or plan to be by 2030. The companies are BP, Chevron, Eni, Exxon Mobil, Shell and TotalEnergies. The projects are mainly focused on SAF and HVO, which Rystad said are expected to comprise nearly 90% of the projected biofuel production.

The projects are mostly greenfield developments, including Chevron’s Geismar plant in southern Louisiana that aims to produce 22,000 bbl/d of biofuel.

Rystad, however, deemed BP as the global frontrunner in bioenergy with a combined 130,000 bbl/d of ethanol and HVO/SAF capacity in its production capacity pipeline.

“With increasing regulatory pressure to adopt SAF, such as Europe’s ‘ReFuel EU’ initiative and expanding mandates in Asia Pacific, biofuels have shifted from being a potential option to becoming an essential component of decarbonization strategies,” Lars Klesse, bioenergy research analyst at Rystad Energy, said in a news release.

Challenge, solutions

Producers face a colossal change given decarbonization goals. As of Nov. 4, the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration still aimed to develop SAF to achieve a 50% reduction in GHG compared to conventional fuel, according to Lewis.

“By 2030, domestic production should be at least 3 billion gallons. And by 2050, it needs to meet 100% of aviation fuel demand, which is projected to be 35 billion gallons [globally],” Lewis said. “Last year domestic production of SAF was 24.5 million gallons. So, we’re talking about producing more than a thousand times the amount that is currently being produced.”

Starting in 2025, all aviation fuel supplied at EU airports must have at least 2% SAF. That percentage rises to 70% in 2050, he said.

“Traditional project financing is effectively unavailable to scale up the production of SAF unless you have a take-or-pay, fixed price contract or some other similar solution that would allow you to project finance building one of these plants,” Lewis added. “To fill that gap pretty much the consensus is that the industry needs clear, consistent and long duration government support, which we can all look around and see that we don’t have any of that. We do have some government support in the IRA, but it’s not long enough to finance a project. And the question about will it be consistent is obviously up in the air.”

Some ways to scale up SAF are already being pursued. These include leveraging other renewables, Lewis said. Renewable diesel plants are being converted, for example, for a cost of about $100 million compared to $400 million to $500 million, he said, depending on incentives.

“Another is to just create more affordable, abundant feedstock: carbon capture, sequestration, access to clean hydrogen. …A lot of the investments by our airline clients are in those technologies to basically make them more possible,” Lewis said.

A shift by energy users to other forms of energy could also free up feedstock needed to produce more SAF. “That obviously will help the price differential between SAF and regular Jet A [kerosene-based fuel] and obviously makes the whole thing more affordable. … Maybe this will all matter next year and maybe it won’t.”

Recommended Reading

Glenfarne Signs on to Develop Alaska LNG Project

2025-01-09 - Glenfarne has signed a deal with a state-owned Alaskan corporation to develop a natural gas pipeline and facilities for export and utility purposes.

Burgum: Feds ‘Will Step In’ to Build Marcellus-to-New England Pipeline

2025-03-12 - Trump administration officials want to greenlight a pipeline to carry Marcellus Shale gas from Pennsylvania into New England states, says U.S. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum.

Shale Outlook: Power Demand Drives Lower 48 Midstream Expansions

2025-01-10 - Rising electrical demand may finally push natural gas demand to catch up with production.

Targa Buys Back Bakken Assets After Strong 2024

2025-02-20 - Targa Resources Corp. is repurchasing its interest in Targa Badlands LLC for $1.8 billion and announced three new projects to expand its NGL system during its fourth-quarter earnings call.

Kinder Morgan to Build $1.7B Texas Pipeline to Serve LNG Sector

2025-01-22 - Kinder Morgan said the 216-mile project will originate in Katy, Texas, and move gas volumes to the Gulf Coast’s LNG and industrial corridor beginning in 2027.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.