Oil industry insiders have probably written off the dusty, shrub-dotted land surrounding Midland, Texas, more times than you can easily count.

But the mighty Midland Basin has persisted—decade after decade, downturn after downturn—to help push U.S. oil production to a new record high.

And as the availability of currently economic onshore drilling locations around the U.S. shrinks, some of the world’s top oil producers are paying hefty premiums to get a piece of the action.

Oil and gas producers spent $234 billion on M&A in 2023, the most in over a decade, according to Energy Information Administration (EIA) figures. The total includes corporate M&A, accounting for 82% of the total announced dealmaking last year, and asset acquisitions.

With high-profile consolidation spilling over into first-quarter 2024, the Permian Basin has seen well over $100 billion in M&A activity get signed in the last 12 months.

That includes the largest deal ever made in the shale oil and gas industry: Exxon Mobil’s $64.5 billion acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources.

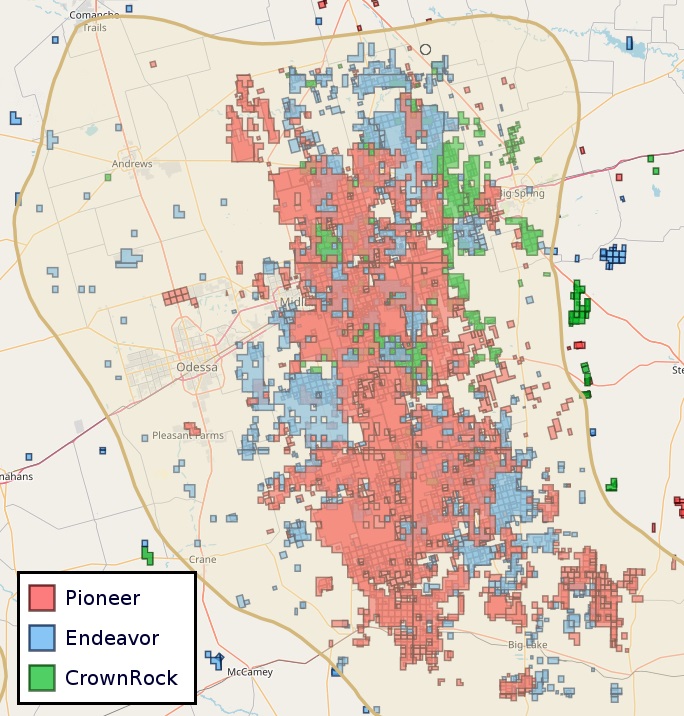

In January, Diamondback Energy announced plans to acquire private producer Endeavor Energy Resources for $26 billion—the largest buyout of a private upstream E&P in industry history.

Occidental Petroleum is also getting deeper in the Permian with a $12 billion acquisition of CrownRock, a joint venture between CrownQuest Operating and private equity firm Lime Rock Partners.

Within a matter of months, some of the largest and least-developed pieces of land in the core of the Midland Basin were plucked off the drawing board.

Add onto those megadeals a deluge of smaller transactions, and operators that have yet to ink a deal are suddenly finding a lot less of the Midland to go around.

Today, the vast majority of the lowest-cost drilling locations across the Permian are already held within the portfolios of a relatively small number of public E&Ps, according to a Wood Mackenzie analysis.

E&Ps have realized that to get their hands on top-quality Permian rock, they’ll likely have to go out and buy it from one, or several, of their competitors.

As the Midland’s core shrinks, where could the next multibillion-dollar deals get signed?

RELATED

Life on the Edge: Surge of Activity Ignites the Northern Midland Basin

Lateral movement

The feeding frenzy underway in the Midland Basin stands in stark contrast to the 1980s, when big U.S. majors were picking up and leaving matured West Texas fields in search of new oil in international locales, like Saudi Arabia and Russia.

U.S. independents, like Parker & Parsley, used the vacuum left in their wake as an opportunity to scoop up additional Permian Basin leasehold for cheap.

Parker & Parsley CEO Scott Sheffield—who later led the company’s merger with T. Boone Pickens’ Mesa Petroleum to form Pioneer Natural Resources—recalled paying “nothing” for those Permian leases during the ’90s and 2000s.

Operators were still drilling vertical Permian wells at that point. But advances in hydraulic fracturing and oilfield technologies, like composite bridge plugs, made it possible for vertical wells in the Permian to target several producing intervals underground, said Ron Dusterhoft, technology fellow at Halliburton and a 40-year industry veteran.

Hitting those secondary targets with vertical wells and hydraulic fracturing enabled operators to produce oil economically in the Midland area once again.

“This was, from my perspective, the second life in the Permian Basin when a lot of people had started to write it off,” Dusterhoft told Oil and Gas Investor.

New technologies breathed a second life into the Permian throughout the 1980s and 1990s. But the Permian’s second act had seemingly run its course by the 2000s, when operators struggled to sustain domestic output.

Total U.S. crude oil output fell by over 44% from 8.97 million bbl/d in 1985 to just 5 million bbl/d in 2008, bottoming out during the global financial crisis, according to the EIA.

As domestic demand for oil and gas continued to rise, conventional wisdom held that the U.S. would be the world’s largest importer of hydrocarbons for the foreseeable future.

It took unconventional risk-taking to break free from that mold.

Horizontal drilling and fracking techniques—pioneered by operators like Burlington Resources, Continental Resources, Lyco Energy and others in the Williston Basin in the late ’90s and early 2000s—proved they could be applied to several unconventional targets in the Permian.

First in the Midland Basin, and later in the more western Delaware Basin, Dusterhoft said.

Operators started drilling horizontal Permian wells, complete with longer and longer horizontal laterals extending for miles deep beneath the red Midland dirt.

By January 2007, crude oil production in the Permian region averaged around 843,000 bbl/d, according to the earliest figures published by the EIA. That dwarfed other onshore plays at the time, like the Bakken (~132,000 bbl/d), the Anadarko (~126,000 bbl/d), the Rockies (~113,000 bbl/d) and the Eagle Ford Shale (~54,000 bbl/d).

It wasn’t until May 2011 that Permian oil output rose above 1 million bbl/d.

“I’m not sure that anyone realized that the Permian had the potential that it has demonstrated today, but I remember Pioneer talking about the huge potential of this region very early on,” Dusterhoft said.

RELATED

Petrie Partners: A Small Wonder

Core competency

Scarcity of top-quality drilling locations is now causing acreage in the core of the Midland Basin to sell for a premium.

But if you were to gaze over a tract of “premium” core acreage in Midland or Martin counties, for example, it might not be clear why one dusty, flat acre would be any more or less valuable than the next.

What operators are chasing in the Midland Basin’s core is a ton of oil production that doesn’t need a ton of money to get it out of the ground.

Companies like Pioneer and Endeavor were two of the largest owners of undrilled land in the core-of-the-core of the play.

To put it another way, these companies owned rights to drill wells that can guarantee profitable returns even in a period of low commodity prices.

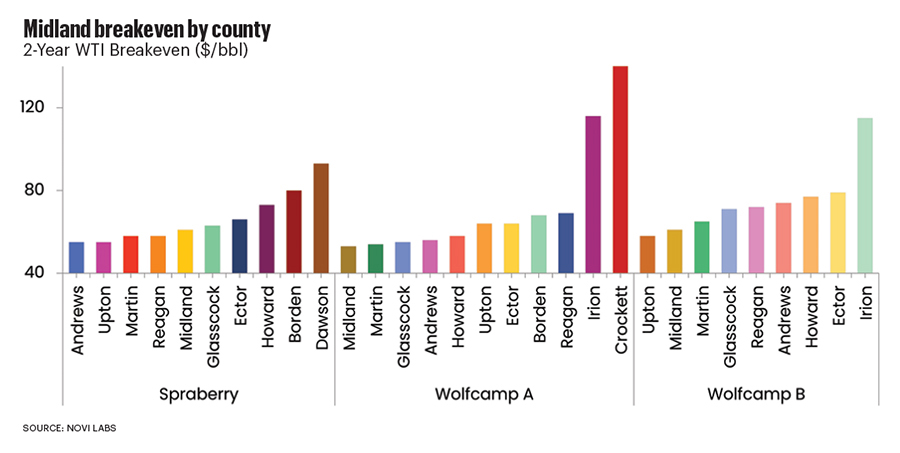

Counties in the core of Texas’ Midland Basin—Midland, Martin, Upton and Glasscock—consistently have some of the lowest breakeven costs across the Spraberry, Wolfcamp A and Wolfcamp B intervals, according to an analysis from Novi Labs.

But the cost curve to drill goes up the further outside of the basin’s core you move.

New wells drilled in the core of the play are generally able to break even after two years with oil prices averaging between $55/bbl and $60/bbl.

But new wells drilled in the fringes of the Midland—Howard, Borden and Dawson counties to the north, and Irion and Crockett counties to the south—would require average oil prices between $90/bbl and $100/bbl over two years to break even.

That huge difference between core and non-core breakevens is one reason why Pioneer, Endeavor and CrownRock sold for a hefty premium between 5-6X their EBIDTA margins.

“It’s really that sweet spot of a deal that companies are willing to pay up for,” said Matt Bernstein, Rystad Energy senior analyst, “where you’re both getting a lot of long-term inventory, and you’re really getting that core-of-the-core, top-tier inventory that’s requiring those higher multiples.”

E&Ps located outside of the core, with lower-tier inventory and higher drilling costs, would not fetch similar multiples if they were carved out by a larger player.

They might nab a 3.5x multiple—similar to some of the take-outs of private equity-backed E&Ps early in the 2023 consolidation wave, Bernstein said.

But after a year of historic consolidation, what’s left of the Midland Basin’s core to be bought?

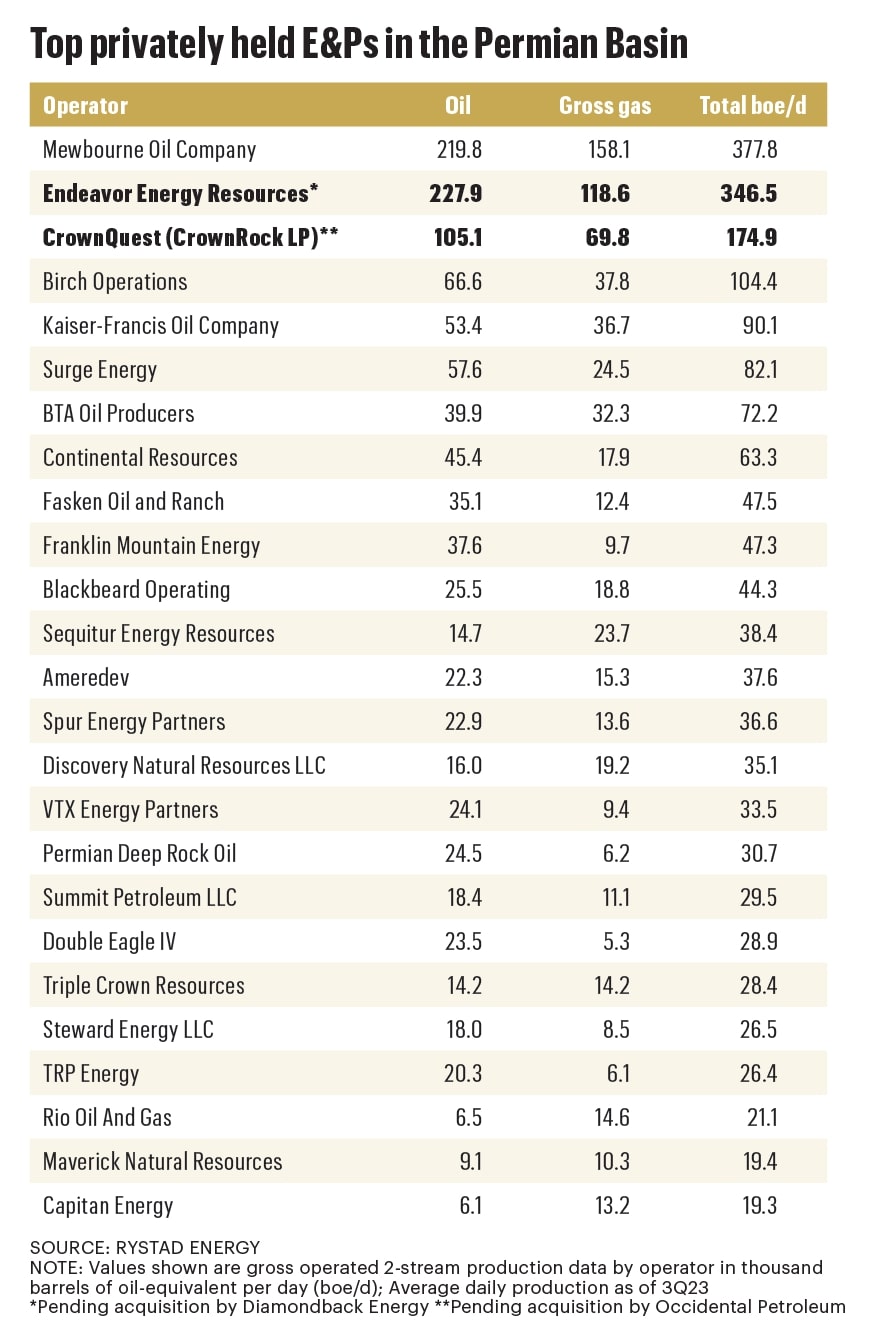

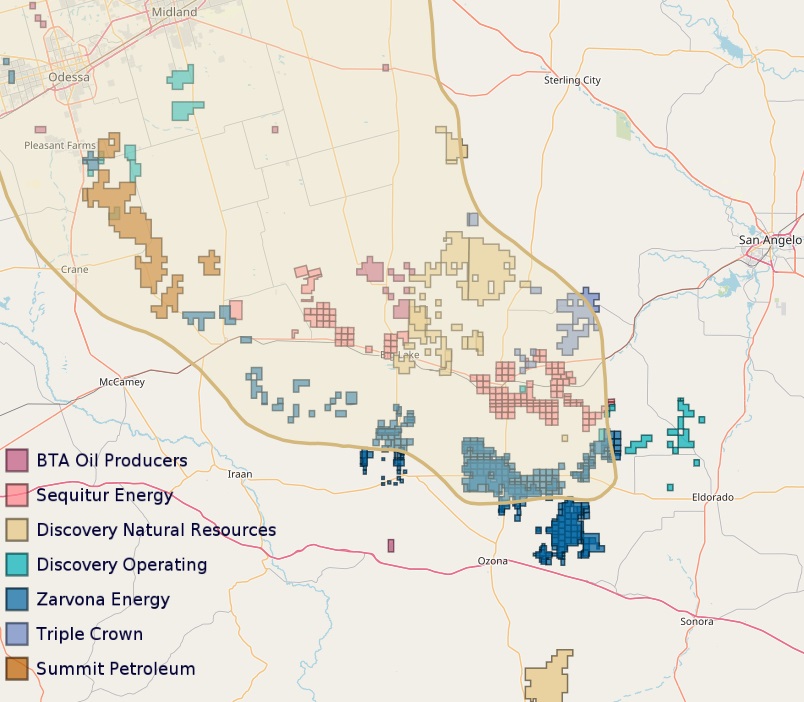

There are still a handful of private E&Ps with attractive inventory portfolios, including Double Eagle IV, Summit Petroleum and BTA Oil Producers, by Rystad’s analysis.

These are the inventory plays: companies with long inventory runways that don’t necessarily produce all that much oil and gas right now.

They differ from E&Ps that are producing healthy volumes of oil and gas but don’t have attractive inventory depth for the long term—the PDP-centric plays.

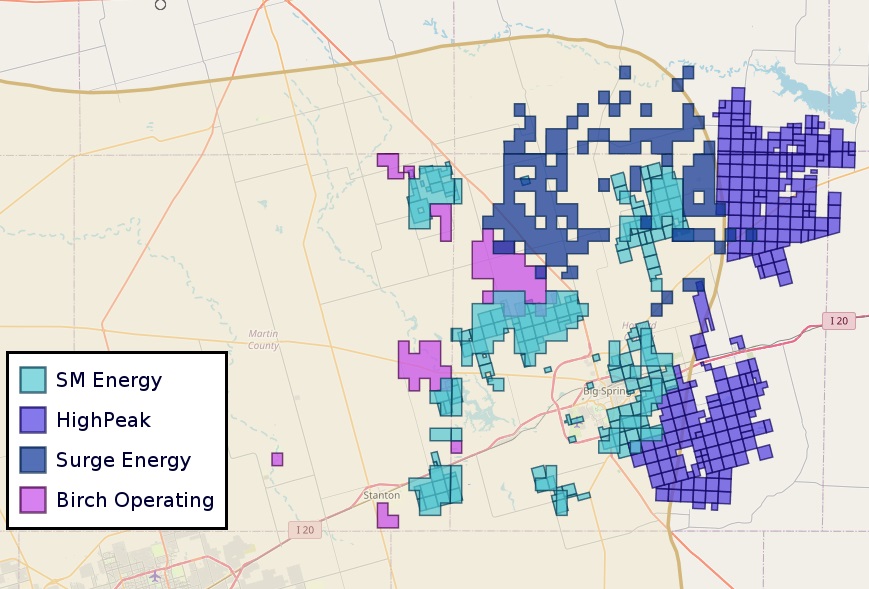

Surge Energy and Birch Operations are two of the top private producers remaining in the Permian Basin, according to Rystad, but their assets are located in the northern reaches of the Midland Basin, primarily in Howard, Borden and Dawson counties, where it’s more expensive to drill.

“Birch, Surge: these are companies that are producing a lot right now, relatively,” Bernstein said. “But again, they’re not probably going to get that same type of multiple, or even close to the same type of multiple, that Endeavor or CrownRock got.”

There are also several public E&Ps that have grown through Permian acquisitions in recent years that could become targets for acquisition themselves.

Civitas Resources jumped into the Permian with nearly $7 billion in acquisitions last year. The company’s $2.1 billion acquisition of Vencer Energy, backed by commodities trading house Vitol, added acreage in the Midland Basin’s core.

Vital Energy—formerly Laredo Petroleum—added to its legacy position in the Midland Basin in deals with private E&Ps last year.

Ovintiv also grew its Midland portfolio by acquiring a package of three EnCap-backed private producers for $4.275 billion.

Permian Resources, which is mostly concentrated in the Permian’s more western Delaware Basin, added PDP-heavy assets in the Midland Basin through a $4.5 billion takeover of Earthstone Energy.

“That’s kind of what I see as the next chapter of this [industry consolidation],” Bernstein said.

There’s also SM Energy, which has operations in the Permian and near the Texas-Mexico border. But SM is getting deeper in the Midland Basin: the company reported increasing its Midland acreage by 37% in 2023.

With a market value of around $5.4 billion, SM appears to be one of the more reasonable acquisition opportunities remaining after this latest wave of consolidation, said Andrew Dittmar, senior vice president at Enverus Intelligence.

“Among remaining SMID caps, for a balance of inventory life and an attractive valuation SM would be near to the top to be positioned for a deal,” Dittmar told Hart Energy.

RELATED

After Record Year, Permian Basin Set for Even More M&A in 2024

Tier jumpers

After months of major industry consolidation, there are few Tier 1 drilling locations left on the market.

Analysts believe that operators in search of greater inventory depth will have to start moving down the list into Tier 2 and Tier 3 acreage locations.

And operators believe that by lowering their oilfield service costs, costs and picking up operational efficiencies, they can move some of those Tier 2 locations into Tier 1 status.

As core acquisition opportunities dwindle, “companies needing inventory are likely to take a harder look at the southern Midland,” a much more fragmented part of the basin, Dittmar said.

Counties in the southern Midland, like those in the north, generally have higher breakeven costs above the $50/bbl range that public investors prioritize.

An operator buying into the area would then look to drive down those breakevens by lowering drilling costs and optimizing spacing.

It’s a story played out across the Permian: spending less money to drill fewer wells with longer horizontal laterals to maintain, or just slightly boost, production.

The southern Midland is also the area that some of the bigger public acquirers from 2023 will likely look toward if they want to sell off non-core portions of their portfolios, Dittmar said.

“Overall, I’d say the southern Midland is one of the remaining bright spots for further consolidation.”

Sequitur Energy, Discovery Natural Resources, Discovery Operating and Triple Crown Resources are among the largest producers with significant footprints in the southern Midland Basin.

RELATED

Analysts: Diamondback-Endeavor Deal Creates New Permian Super Independent

Dig deeper

Given the chatter about historic consolidation, inventory depletion, scarcity, peak oil demand looming—it might seem like the Permian is nearing the end of its run.

Analysts and industry experts say that’s not remotely the case. The Permian Basin is expected to be the primary driver of U.S. oil production growth for decades to come.

The most common subsurface targets for drilling, the main Spraberry and Wolfcamp intervals, are pretty well developed at this point.

Operators have targeted the Spraberry trend in the Midland Basin with vertical wells since at least the late 1940s, according to the Bureau of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin. The deeper Wolfcamp zones have been targeted more recently.

But once the most popular Wolfberry plays are drilled up and their recoverable resource exhausted, operators will drill deeper.

“The really interesting thing about the Permian Basin is that there are now several horizontal targets, meaning that there is room for a very large number of wells and a massive amount of reservoir contact made possible through horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing,” Dusterhoft said.

Enverus has identified around 25,000 additional geologically viable locations that imply future upside in more extensional, fringier portions of the Midland Basin.

The average breakeven for these geologically-viable locations is higher—between $70/bbl and $80/bbl—Enverus reported at the end of 2023.

With the primary Wolfberry targets heavily developed, the Middle Spraberry and the deeper Wolfcamp D intervals show the most viable promise in the Midland Basin, according to Enverus’ analysis.

“The Permian has proven to be an amazing petroleum system that has been highly productive for close to a century, making it a pretty amazing story,” Dusterhoft said.

RELATED

Enverus: E&Ps Eye Deeper, Fringier Targets as Permian Basin Matures

Recommended Reading

Amplify Updates $142MM Juniper Deal, Divests in East Texas Haynesville

2025-03-06 - Amplify Energy Corp. is moving forward on a deal to buy Juniper Capital portfolio companies North Peak Oil & Gas Holdings LLC and Century Oil and Gas Holdings LLC in the Denver-Julesburg and Powder River basins for $275.7 million, including debt.

Ring Sells Non-Core Vertical Wells as it Closes in on Lime Rock

2025-03-06 - Ring Energy Inc. said it sold non-core vertical wells with high operating costs as it works to close an acquisition of Lime Rock Resources IV’s Central Basin Platform assets.

Diamondback Acquires Permian’s Double Eagle IV for $4.1B

2025-02-18 - Diamondback Energy has agreed to acquire EnCap Investments-backed Double Eagle IV for approximately 6.9 million shares of Diamondback and $3 billion in cash.

Chevron Buys 15.4MM Shares of Hess Stock on Open Market

2025-03-17 - Chevron Corp. reported that between January and March 2025 it purchased about 5% of Hess Corp. shares, according to a Securities and Exchange Commission filing.

DNO to Buy Sval Energi for $450MM, Quadruple North Sea Output

2025-03-07 - Norwegian oil and gas producer DNO ASA will acquire Sval Energi Group AS’ shares from private equity firm HitecVision.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.