Oil wells easily outnumber people in Loving County, Texas.

Loving (population: 43) is the least populous county in the nation, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

But it’s the epicenter of drilling activity on the Texas side of the Delaware Basin—a portion of the Permian from where operators expect to see decades of future crude oil production growth. The Delaware, extending from West Texas into southeastern New Mexico, is less developed than its eastern Permian cousin, the Midland Basin.

“We tend to think with today’s activity and technology, if Midland’s got 15 to 20 years left, the Delaware is probably in the 20- to 25-year range,” said Jason McIntyre, Halliburton’s Permian area vice president. “However we’re very long on Permian Basin production.”

Major operators are scrambling to buy the best acreage in the Midland, which has seen over $100 billion in corporate M&A and asset acquisitions over the past 12 months. That’s because the Midland has some of the most productive and lowest-cost rock to drill in the Lower 48.

The Delaware Basin is a different beast.

The drilling targets in the Delaware are deeper, pressures are higher and the potential for H2S sour gas is much higher than in the Midland Basin.

Power and water infrastructure constraints also present unique challenges to drill in one of the least-developed and sparsely populated places in the country.

To make matters more complicated, the core of the Delaware oil play extends into New Mexico, where operators face a more stringent regulatory regime than south of the border in the Lone Star State.

But the Delaware’s prize—bountiful oil output potential and decades of future upside—is too sweet to pass up for many of the nation’s top producers, including Exxon Mobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, EOG Resources, Occidental Petroleum, Devon Energy, Coterra Energy and Apache.

“A lot of operators that operate in both basins, they tend to see maybe more prolific production in the Delaware,” McIntyre said. “But it comes at a higher development cost.”

RELATED

Mighty Midland Still Beckons Dealmakers

Exploring New Horizons

Harold Hamm made himself a billionaire wildcatting in the Bakken and in the Midcontinent, but in recent years, the Delaware’s potential has become too much for him to resist.

He surprised industry insiders in late 2021, when his Oklahoma City-based company, Continental Resources, made an entrance into the Permian with a $3.25 billion acquisition of Pioneer Natural Resources’ Delaware assets.

Horizontal development throughout the Permian already was a well-oiled machine; Continental was late to the game.

And the company’s new asset was toward the southern part of the Delaware—Texas’ Reeves, Ward, Winkler and Pecos counties—outside of what’s largely considered the play’s core oil window.

It wasn’t long after Hamm’s debut in the Permian that Doug Lawler, former president and CEO of Chesapeake Energy, joined Continental as COO in early 2022.

The Pioneer acquisition added around 92,000 net Delaware acres; oil volumes averaged approximately 35,000 bbl/d (50,000 boe/d).

The initial Pioneer deal delivered Continental “a relatively low amount of production” and undrilled inventory, Lawler told Oil and Gas Investor (OGI).

But the potential for future exploration also attracted Continental to Pioneer’s Delaware asset.

“The timing was really based on when an opportunity became available for us to pursue some of that exploration without having to pay an extremely high premium because of a lot of associated current production,” said Lawler, who took over as Continental’s CEO at the start of 2023.

Texas Railroad Commission (RRC) records show Continental has mostly targeted the popular Wolfcamp and Bone Spring intervals with new wells drilled since taking over the Delaware asset.

—Doug Lawler, CEO, Continental Resources

But the wildcatting producer is also delineating locations to drill the deeper Woodford interval in Winkler and Pecos counties.

Continental has submitted production data on three Delaware Woodford wells drilled at depths ranging between 13,000 ft and nearly 16,000 ft.

The two Winkler County wells (8,621-ft lateral; 9,714-ft lateral) have produced a combined 248,747 bbl since coming online in March 2023, per the RRC’s most recent figures.

A Magnolia State Unit well (9,760-ft lateral) in Pecos County has produced 144,590 bbl since coming online in April 2023.

Continental’s Delaware oil production reached nearly 13.43 MMbbl (36,788 bbl/d) for full-year 2023.

Continental, which went private in a $4.3 billion buyout by the Hamm family in 2022, also has quietly added leases on the Midland side of the basin for future exploration. RRC records show Continental became operator on dozens of new leases in Midland and Ector counties, Texas, in November 2023.

“Our main focus is on the Delaware side, but we’re looking also on the Midland side, as well,” Lawler said.

The new Midland County leases, 87 in total, were transferred to Continental Resources by a subsidiary of Occidental Petroleum, RRC records show.

Continental also assumed operatorship of a handful of leases from Occidental in nearby Ector County, just to the west across the county line, in November. The Midland and Ector assets produced about 76,000 bbl of crude oil—an average of around 825 bbl/d—from November 2023 through January 2024, their first three months under Continental.

Legacy vertical wells drilled on most active leases have targeted the Dora Roberts Field.

Occidental recently disclosed selling “certain non-core proved and unproved properties in the Permian Basin for $202 million” in its latest annual report. Occidental recorded a net gain of $142 million from the divestment.

Continental declined to discuss details of the lease transfers in Midland and Ector counties, but said it continues to look at Permian M&A.

“While we prefer not to comment on any specific transaction in detail, you can expect Continental to continue to be active with additional bolt-ons and new acquisition opportunities in the basin,” a Continental spokesperson told OGI.

With the wave of consolidation underway across the Midland Basin, experts anticipate M&A will take place in the Delaware.

But there aren’t as many potential combinations left after a record year of upstream transactions. Among private Permian producers, Mewbourne Oil and Continental stand out with the most attractive portfolios of undrilled inventory, said Rystad Senior Analyst Matt Bernstein.

“It’s really Mewbourne and Continental, and then everybody else right now as far as inventory goes,” Bernstein said.

But in an environment dominated by large-scale consolidation, Continental appears to be focused on growth and exploration—not necessarily selling assets.

Continental plans to invest around $1 billion per year over the next four to five years across the Delaware and Midland basins, Lawler said.

The company aims to double its current daily production, around 70,000 boe/d, by 2028.

“We think there is a significant amount of opportunity for a company like Continental to grow in the Permian Basin,” Lawler said. “We see that through existing inventory. We see that through exploration, and we see that through efficiencies on the operating and technical sides.”

RELATED

Barnett & Beyond: Marathon, Oxy, Peers Testing Deeper Permian Zones

Riding The Line

Before the $5.75 billion combination with WPX Energy in early 2021, Devon Energy’s Delaware footprint was mostly concentrated on the New Mexico side of the basin.

That presented challenges to growing in the Permian, Devon’s Delaware Basin Vice President John Raines told OGI.

“Your primarily development going forward pre-merger for Devon is on federal acreage,” Raines said.

Heading into 2020, about 40% of Devon’s Delaware leasehold resided on federal lands in New Mexico, per regulatory filings.

When Democrats retook the White House, many operators questioned how the federal regulatory landscape for oil and gas leasing and permitting might change.

“You want some optionality,” Raines said.

WPX Energy had options: A big portion of WPX’s Delaware assets were located on the Texas side of the basin.

The combination with WPX yielded a combined 400,000 net Delaware acres, with 35% of the leasehold on federal land.

Raines now oversees Devon’s most important asset: Roughly 60% of the company’s planned capital investment will flow into the Delaware in 2024.

But despite a more favorable regulatory regime in Texas, operators are still drilling for oil in New Mexico. The core-of-the-core of the basin’s oil fairway extends considerably into New Mexico, unbound by the borders on the surface.

Devon still plans to concentrate 70% of its Delaware budget in New Mexico this year, the company said during its fourth-quarter earnings call with analysts.

But operating in the New Mexico Delaware requires some flexibility: For example, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management recently withdrew seven parcels covering over 3,000 acres from an upcoming lease sale in southeastern New Mexico.

Devon had 17 rigs operating in the Delaware at the start of the year, targeting the basin’s most popular Bone Spring and Wolfcamp intervals.

Devon COO Clay Gaspar highlighted some recent gushers being drilled in southeastern New Mexico during the company’s earnings call:

The eight-well Clawhammer pad on federal leasehold in the Stateline development area produced 3,900 boe/d in the fourth quarter, the highest productivity per lateral foot of any of Devon’s wells that quarter.

The Clawhammer project featured two-mile laterals targeting multiple intervals in the Wolfcamp A formation.

Devon also brought online 11 three-mile laterals in the Cotton Draw area across the Avalon, Bone Spring and Wolfcamp intervals during the quarter.

Raines said Devon typically thinks about developing its Delaware projects in “flow units” by different sections, or intervals, in the stratigraphic column.

These flow units are broken down by their own pressure regimes, spacing needs and completion designs, allowing Devon to simultaneously develop multiple stacked pay zones at once—a concept the industry commonly refers to as cube development.

An Upper Bone Springs flow unit would generally include the Avalon and the first and second Bone Spring formations.

Drilling deeper, a Lower Bone Springs flow unit in some cases might include the second Bone Spring Sand, the third Bone Spring Lime and the third Bone Spring Sand. In the Wolfcamp formation, an Upper Wolfcamp flow unit might contain that third Bone Spring Sand—depending on the area—the Wolfcamp XY and, generally, the Wolfcamp A.

Devon also thinks about a deeper Wolfcamp flow unit containing the Wolfcamp B’s various landing zones and the Wolfcamp C.

It’s not an exact science. The subsurface nomenclature tends to change from operator to operator, Raines said. What you’ll find underground really depends on where you end up drilling.

“The zones we include in the Upper Wolfcamp flow unit in, say, a Rattlesnake versus a Cotton Draw verses a Potato Basin—those can look very different in terms of how you land and space your wells,” Raines said, “because of those geologic inflows, outflows and changes from area to area.”

Devon has over 10 years of resource opportunity remaining in the Delaware Basin, but the company also is keeping an eye on opportunities for future exploration. Deeper formations like the Woodford or Barnett have yet to become major targets in the company’s Permian drilling plans.

“It’s deeper, it’s more expensive,” Raines said. “Even though we think the resource is there, it may not be as competitive for us currently.”

RELATED

There and Back Again: Rick Muncrief and Devon Energy’s Permian Journey

Running Room

U.S. upstream M&A activity approached $200 billion in 2023, but the bulk of the dealmaking centered on the Permian Basin, most of that in the Midland. Some of the Permian’s oldest and largest producers were snapped up by larger operators in a matter of months.

The most prominent example of onshore consolidation is Exxon Mobil’s roughly $60 billion acquisition of Pioneer, a legacy Permian pure-play. Exxon anticipates closing the Pioneer deal during the second quarter, pending regulatory approval.

Diamondback Energy is scooping up Endeavor Energy Resources for $26 billion, the largest buyout of a private U.S. upstream company in the industry’s history, per Enverus Intelligence Research data.

Occidental is wading further into debt to acquire private Midland producer CrownRock and selling off non-core assets to deleverage. Occidental plans to monetize between $4.5 billion and $6 billion in non-core domestic assets within 18 months of closing the CrownRock deal. That’s part of the reason Occidental sold the legacy Permian assets in Midland and Ector counties to Continental late last year.

But the drumbeat of consolidation is slower in the Delaware Basin, at least for now.

Compared to the Midland, parts of the Delaware are still much more fragmented with privately held producers. But core parts of the Delaware have attracted M&A from mid-sized public producers in the past year and change.

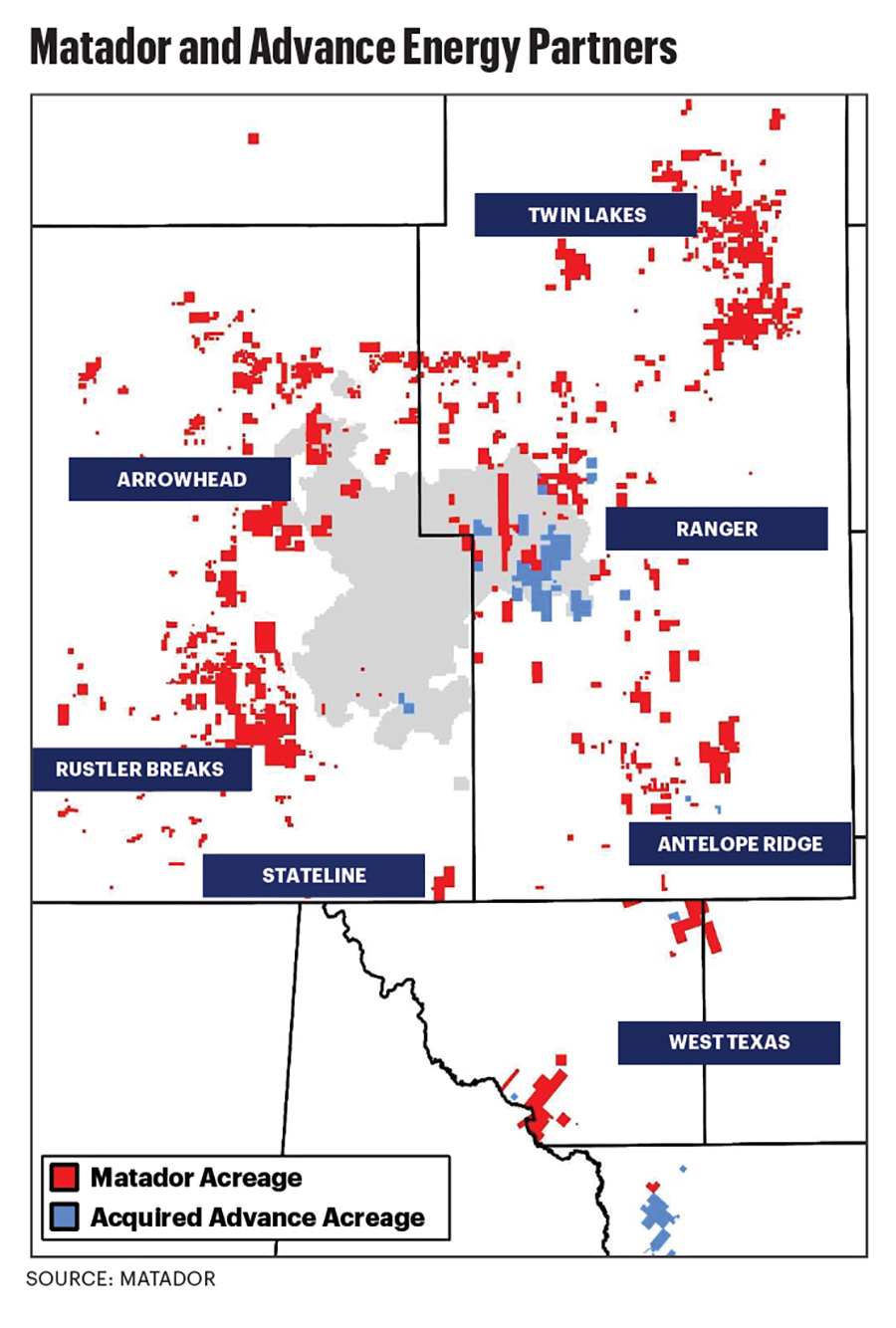

Matador Resources closed a $1.6 billion acquisition of EnCap-backed Advance Energy Partners in early 2023. Matador’s largest acquisition in company history included about 18,500 net acres in Lea County, New Mexico and in Ward County, Texas.

Formerly a Colorado pure-play, Civitas Resources made its foray into the Permian last year by picking up NGP-backed privates Hibernia Energy and Tap Rock Resources for $4.7 billion in cash and stock.

The Tap Rock acquisition included around 30,000 net acres and average production of 59,000 boe/d (52% oil) across Lea and Eddy counties, N.M., and Loving County, Texas.

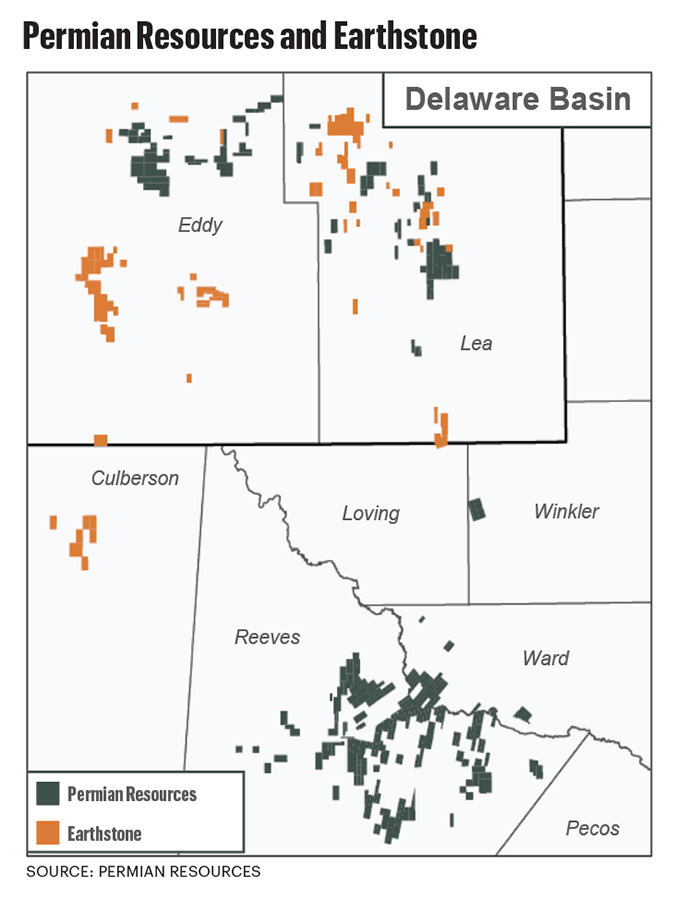

Permian Resources’ $4.5 billion takeover of Earthstone Energy gave the company additional scale in New Mexico, though a smaller entry into the Midland Basin.

In June, Vital Energy—formerly Laredo Petroleum—inked a $540 million deal to enter the Delaware by acquiring Forge Energy from EnCap. Non-operated partner Northern Oil & Gas covered 30% of the purchase price. Vital followed with additional Delaware dealmaking.

Large-cap players are starting to deepen their roots in the Delaware, too.

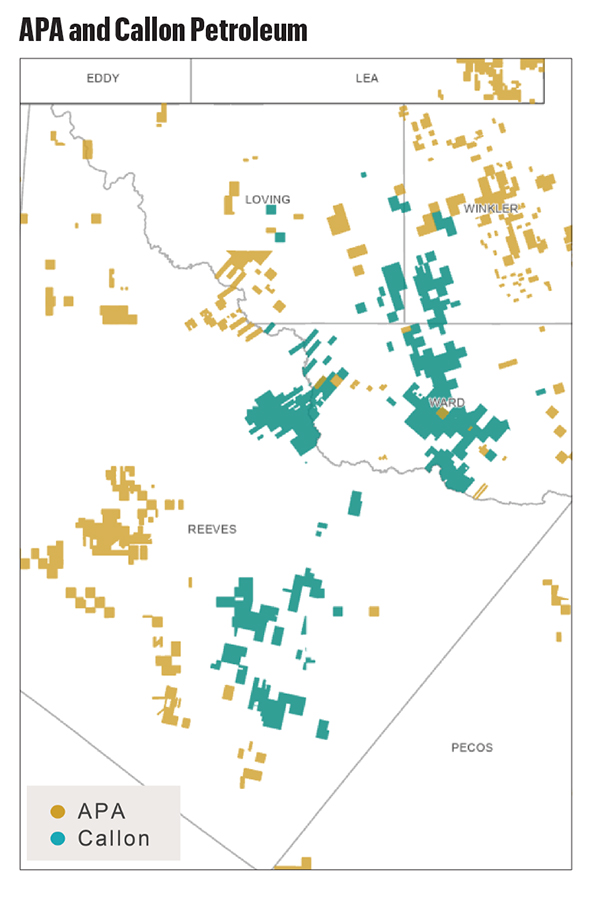

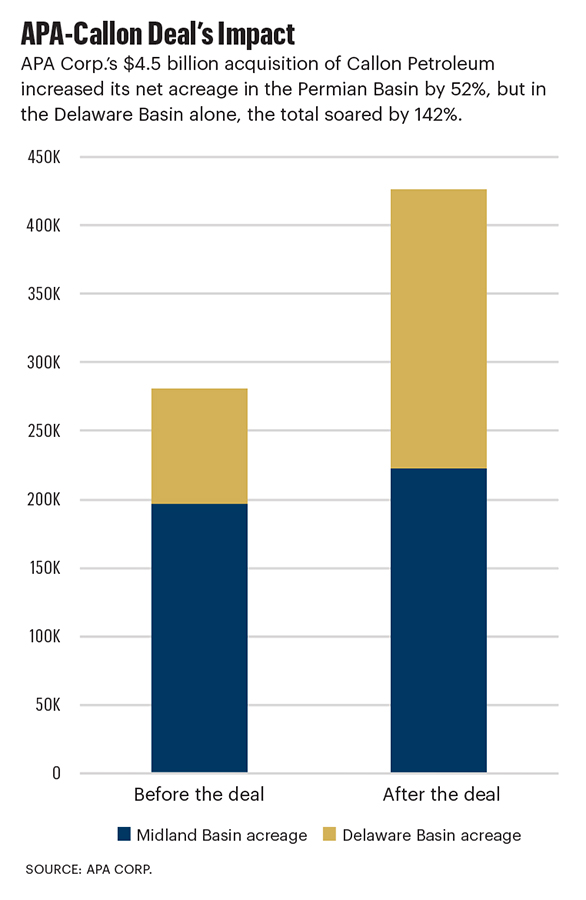

APA Corp., parent company of Apache, closed a $4.5 billion acquisition of Callon Petroleum on April 1. Before the Callon deal, Apache’s Permian position was heavily weighted on the Midland side of the basin, where the company held 197,000 net acres. Apache had about 84,000 net Delaware acres before the Callon deal.

Callon brought to Apache about 119,000 net Delaware acres across Ward, Reeves, Winkler and Loving counties, according to RRC data. Callon also had a smaller 26,000-acre footprint in the northern Midland Basin, including Andrews, Borden, Dawson, Howard, Midland and Martin counties, Texas.

“It’s an oil asset, and we like that [Callon] balances our portfolio across the basin,” said Sara Reilly, vice president of U.S. assets at Apache. “We’re excited to be able to add to our portfolio both in the Midland Basin and, in particular, in the Delaware Basin.”

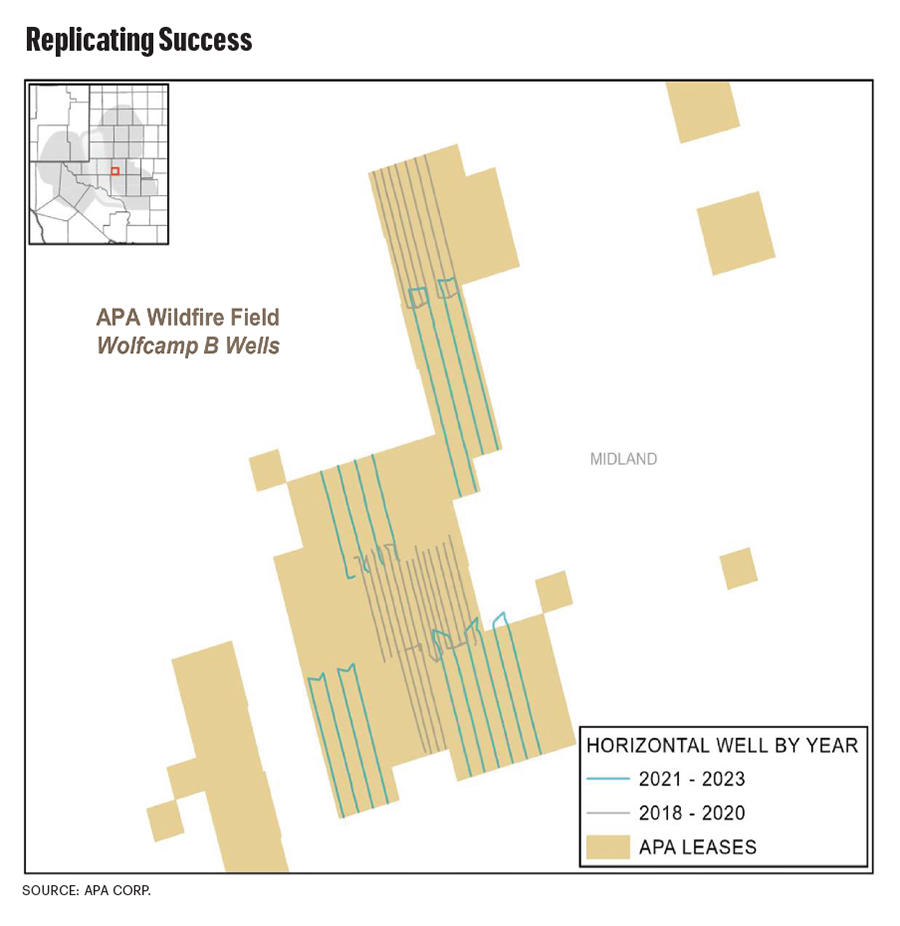

Apache has spent considerable time and resources testing well spacing and D&C designs to boost Delaware Basin well productivity.

Reilly said Apache is applying its skills learned from drilling in the southern Midland Basin to improve resource recovery in the Delaware. Under the updated workflow, Apache is widening the space between wells per section and using larger fracs. It’s led to a notable uplift in overall productivity compared to the company’s designs about five years ago.

“More recently, the performance of some of the Callon wells has significantly improved, which has demonstrated that their acreage has a lot more potential than [what] may have been previously perceived,” Reilly said.

“We’re excited to apply our unconventional technical expertise and our proprietary workflows to drive further significant improvement on those properties,” she said.

Gary Clark, Apache’s vice president of investor relations, said the Callon acquisition also helps APA better stand out as a Permian-weighted stock.

“Permian acreage, cash flows and production get more highly valued than just about any place in the world,” Clark said. “We think there’s a pretty good opportunity for multiple expansions as well.”

It’s a similar story to what Callon itself saw play out last year as the company exited South Texas to become a Permian-focused pure play.

Callon announced plans to acquire Permian-based Percussion Petroleum Operating II and sell its Eagle Ford Shale assets to Ridgemar Energy Operating after markets closed May 3, 2023. From that point to Jan. 4, 2024—the day APA Corp. announced plans to acquire Callon—Callon’s stock price grew by nearly 13%.

RELATED

Analysts: APA Takes Callon Off Board as Permian M&A Wave Hits ‘24

Powering the future

Operators are positioning the Delaware Basin as a key driver of U.S. crude production for decades, and the future of domestic crude volumes are depending on it.

Chevron plans to tap its Delaware acreage in Texas and New Mexico for drilling locations at least through 2040, the company told investors.

But these plans will matter little if infrastructure bottlenecks—natural gas takeaway and processing, water logistics and electricity capacity, for starters—continue to plague the basin, said Raines of Devon Energy.

“Infrastructure is still probably one of my biggest themes and one of the things I’m focused on the most,” he said. “A lot of folks think gas and oil. I’m increasingly focused on water and power.”

The Midland Basin produces a lot of water, but the Delaware produces “significantly more,” Raines said. Being intentional about building out water transport is critical for Devon in the Delaware.

Power shortages are becoming an issue for grid managers across the U.S., but power availability is another top concern in the Delaware—one of the most sparsely populated regions in the Lower 48.

It’s not just electric vehicles; fracking is going electric, too. Oil and gas operators are increasingly finding ways to reduce diesel consumption by turning to natural gas for electric power to reduce emissions associated with drilling.

“Just generally for the basin, you’re seeing demand for power dramatically outpace the ability of utilities to supply that power,” Raines said.

Devon is in good shape with its power needs right now, but operators have concerns about growing power demand outstripping supply as the basin scales up.

Diamondback Energy recently inked a non-binding agreement to explore deploying small-scale nuclear reactors around its Permian footprint to power its drilling needs for decades.

To manage its own power needs, Devon is evaluating a multi-year process to develop an interconnected microgrid across its Delaware development areas. Devon would set up centralized power generation in each development area using large-scale natural gas turbines—powered by an abundant supply of gas stranded in the basin. The company has some of its own power lines in those areas to manage power distribution.

“It’s something we’re diving into,” Raines said. “We’re in the process of making that transition now.”

And with so much stranded gas in-basin and growing power demand, Devon could become well-positioned to sell power to other operators or demand centers in the area.

Raines admits there’s a laundry list of regulatory concerns about becoming a pseudo-utility provider, tangoing with the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) and the Southwest Power Pool in New Mexico.

“It’s a little daunting because it’s new,” he said. “I didn’t anticipate being in the power business a few years ago.”

Recommended Reading

ADNOC Contracts Flowserve to Supply Tech for CCS, EOR Project

2025-01-14 - Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. has contracted Flowserve Corp. for the supply of dry gas seal systems for EOR and a carbon capture project at its Habshan facility in the Middle East.

Tamboran, Falcon JV Plan Beetaloo Development Area of Up to 4.5MM Acres

2025-01-24 - A joint venture in the Beetalo Basin between Tamboran Resources Corp. and Falcon Oil & Gas could expand a strategic development spanning 4.52 million acres, Falcon said.

E&P Highlights: Jan. 21, 2025

2025-01-21 - Here’s a roundup of the latest E&P headlines, with Flowserve getting a contract from ADNOC and a couple of offshore oil and gas discoveries.

VoltaGrid to Supply Vantage Data Centers with 1 GW of Powergen Capacity

2025-02-12 - Vantage Data Centers has tapped VoltaGrid for 1 gigawatt of power generation capacity across its North American hyperscale data center portfolio.

Judgment Call: Ranking the Haynesville Shale’s Top E&P Producers

2025-03-03 - Companies such as Comstock Resources and Expand Energy topped rankings, based on the greatest productivity per lateral foot and other metrics— and depending on who did the scoring.

Comments

Add new comment

This conversation is moderated according to Hart Energy community rules. Please read the rules before joining the discussion. If you’re experiencing any technical problems, please contact our customer care team.